Kevin Henson has been answering calls to horrific accident scenes for at least 34 years. The trained paramedic and retired fire chief still grimaces a little when thinking about the worst accidents he’s attended. Many of them involved motorcycles.

But there’s one item he never reached for in a trauma event: a first-aid kit. When limbs have been torn, rib cages punctured, and riders are suffering a multitude of life-threatening injuries, a Band-Aid just won’t suffice.

Kevin lives in Angel Fire, New Mexico, and his longtime girlfriend, Dr. Debbie Grady, practices family and urgent care medicine in Albuquerque. They stopped by for a visit while out on a sunny Sunday ride with their pair of BMW 1250 GSs. I asked about the homemade medical kits attached to the back of their bikes, the ones sporting medical cross emblems and MOLLE straps.

“It’s a kit that’s set up for quick emergencies and for things that can just ruin your trip,” Kevin said.

Where to put your trauma kit

The bag, with a created emblem and name to identify its contents, was a special order from a friend who doesn’t specialize in making medical bags for the public. “I have no idea where to find one,” he said, emptying the contents of his trauma kit on my coffee table. “But this is what you need in one.”

First, it is important to have a medical emblem on the exterior of your trauma kit, attached visibly to your motorcycle, so that other riders or motorists know which bag to go to first. “That way, they’re not fumbling around in your gear and wasting time,” Kevin said.

My friend and riding buddy, Steven Scott Polk of Dallas, Texas, also a retired fire chief, keeps his trauma kit strapped to the back of his BMW 1250 GSA within easy reach. It likewise bears a large, red medical cross. He bought his waterproof first-aid pouch from Giant Loop. Unlike Kevin, Steven is trained only as an emergency medical technician, so he asked for help from a paramedic buddy to put his kit together.

“What you’re doing is controlling the bleed,” Steven said. “You don’t need Neosporin and aspirin. Stopping the bleeding saves life and limb. Chances are if you have a wreck, there’s going to be some trauma involved, broken ribs, and road rash. You’re going to need the correct bandages, and you also need to know how to do CPR.”

Steven recounted a Memorial Day trip in which the motorcyclist behind him was clipped by a car. “It severed his leg, and luckily there was a surgeon behind him, so he used his belt as a tourniquet and saved his life,” Steven said.

But back to Kevin’s living room instruction.

It’s really about stopping the bleed

“The things you need quickly for the stuff that can hurt you badly don’t need to be buried at the bottom of your bag,” Kevin said. “IV fluid by itself won’t save your ass, so it’s in the bottom of my bag, but my tourniquet is at the top. This is all about stopping the bleeding. Once you teach someone how to use a tourniquet, it takes maybe 20 seconds to apply it, and it controls uncontrolled bleeding of the extremities. The first time I ever used one was in a motorcycle accident. He had no helmet on, no protective gear, it was hotter than [expletive], and he had amputated his leg on a guard rail. We actually used two tourniquets on him that day.”

Like Steven, Kevin is frank in describing the horrors of motorcycle accidents. After 34 years, he’s lost count of the ones he has attended, but he’s seen enough to know it usually goes one of two ways. “It’s either a minor injury you can easily treat in the field, or it’s a multisystem trauma patient, and if you’re a multisystem trauma patient, and you don’t have a helmet on, you’re dead. In fact, most of the dead people I have seen were not wearing a helmet. The people who are also dead are the ones in head-on accidents with cars.”

The sole purpose of a trauma kit, he said, is to stabilize a patient by stopping the bleeding until help can arrive, and since we adventurers are usually out in the backcountry, that could mean hours. Until recently, there were only two rescue helicopters with winches available in the State of New Mexico for pulling victims from remote areas that would otherwise take hours to traverse by car or ambulance. “A few weeks ago, one of them crashed, so now there’s only one left, and it’s in Albuquerque,” Kevin said. Such trauma kits don’t apply solely to motorcyclists; overlanders, mountain bikers, and serious hikers are also trained in the benefits of swift and effective emergency medical treatment in remote areas.

What you’re going to need

Kevin said that a device as simple as a tourniquet could keep an accident victim alive until real help can arrive on the scene. He picks up a C-A-T (combat application tourniquet) from North American Rescue. “This is the No. 1 selling tourniquet.” He picks up another. “The SAM XT is better but a little harder to use.”

Debbie rifles through the goods and picks up a pair of trauma shears. “These will cut through pennies,” she adds. “The first thing you want to do is get their gear off.”

Kevin chimes in: “If someone is critical, get them naked. We call it the box, which is chest to belly.” He picks up more items. “You need gloves. You need an EpiPen. It’s an absolute life-saver for anaphylaxis. I’ve treated probably 50-60 people, but without it, you’re dead, and with it, you’re alive.” Kevin explains that motorcycle riders, when stung by a bee or wasp, are often stung on the neck since it’s the most exposed part of the skin when riding. “I’ve had that happen to myself twice.”

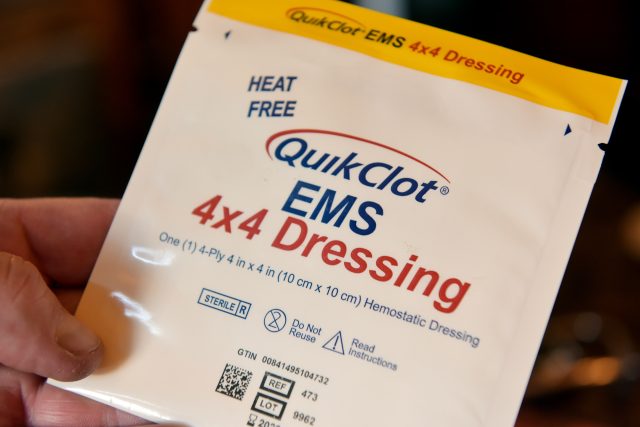

He continues with the products. “You need normal bandages, 4x4s. You need QuikClot. This helps with bleed. If you go over your handlebars, and your belly has a puncture wound, this will help clot the bleeding until they can get to a surgeon.” He picks up another package. “This you use to pack a belly or chest with an open wound. You can’t put a tourniquet on your belly, so you open this and use your thumbs—there are 12 feet of this [stuff] in here—and you keep packing and packing and packing. It creates pressure where the bleed is, and the hemostatic benefit causes the bleed to stop. You also need gauze impregnated with hemostatic dressing. Everything in this bag is bleeding control with the exception of the EpiPen.”

The contents of his kit don’t stop there. “This is occlusive dressing impregnated with gauze, and both the dressing and the wrapper are bandages. They’re for sucking chest wounds from a branch, a tree, a mirror, or whatever. Also, you need a splint for a broken wrist, ankle, foot, arm, whatever, and you can buy them flat or rolled.”

He pulls out a rubber mask. “This is mouth to mask; if someone can’t breathe, and there’s blood in the way, you’d use this.”

Don’t forget the training

I wondered how he got all this stuff into one little sack. I also wondered about training. If you can’t ride continuously alongside Kevin or another medic, consider taking this free online course, stopthebleed.org/. Kevin says the contents of his kit cost about $100 to make. There are companies that make ready-made trauma kits, but Kevin said most don’t have what’s needed in an emergency situation.

I found this Mobility Trauma Kit by Fieldcraft Survival at fieldcraftsurvival.com, complete with most every item Kevin has and everything I do not know how to use. Fortunately, Fieldcraft also offers in-person courses with interactive classes and demonstrations. You can read more about Fieldcraft Survivals MTK here.

And then, there are common sense practices that help with prevention. The biggest travail of moto adventure traveling is dehydration, Debbie said. Both she and Kevin agree that if you’re not experiencing the urge to urinate every hour while riding, you’re not drinking enough fluid. “In fact, by the time you get thirsty, you’re already dehydrated,” Debbie said.

She and Kevin are medical volunteers for the GS Giants Rally each year in Dolores, Colorado. “We put charts in the bathroom with what color your urine should be, and if it’s not within an acceptable range, you need to start drinking water. And if you’re riding with a group and someone is falling over or wobbly, hydrate them immediately.”

Don’t leave out the medicine

He and Debbie also carry medicines in a small bait box in case of an emergency. It could be that someone has become dehydrated from a foodborne illness, or maybe they need pain medication until help can arrive. Or, it could be something simple like a urinary tract infection, which delivers a tremendous amount of pain and fever if left untreated—not something you want to experience in the middle of the Wyoming BDR. The couple recommends carrying medications like Motrin, Benedryl, and Pepto Bismol, along with skin adhesives like Dermabond and Steri-Strips. “They’re great for a busted knuckle or a head bleed,” Kevin said. “Super Glue, while it’s not preferred, also absolutely works.”

Steven said he’s dumbfounded that more motorcyclists don’t carry the right medical gear or know how to use it. Even the industry standard of ATGATT (All the Gear, All the Time) isn’t practiced the way it should be, and most motorcyclists don’t know what to do in an emergency.

“If you’re in a motorcycle group, get a nurse or other medical professional to come to demonstrate how to stop the bleed in the event of an emergency,” he said. “It’s as simple as having a course at a monthly meeting.

“I really don’t know what the deal is. We ride motorcycles, and most motorcyclists think they’re invincible. We’re already up against a wall with people thinking they don’t need helmets because nothing will happen to them, but I ride with a trauma kit because I might come upon an accident, or it could be me or someone I’m riding with. I want someone to see it who knows how to use it.”

Editor’s Note:

This article is not intended to be a “how-to” guide. Seek a medical professional’s advice if compiling your own kit and medical training to ensure you know how to use everything in it.

Our No Compromise Clause: We carefully screen all contributors to ensure they are independent and impartial. We never have and never will accept advertorial, and we do not allow advertising to influence our product or destination reviews.