Ever since our early ancestors ventured beyond the cave and returned to tell about it, the desire to share in our exploits has become nearly as important as the outing itself. More than just accounts of our time away from home, travel stories enrich our experiences through creative introspection and serve as muse for continued wanderings. And, not to put too fine a point on it, can even put cold hard cash in our pockets.

For the modern travel writer, or would-be travel writer, the internet has introduced endless possibilities from the ubiquitous social media post to polished editorial works appearing on high profile web sites. Although print media has dried up considerably as of late, there are still dozens of outlets where a well written yarn can find a home.

Dispensing with a clever segue, I’ll skip to the chase. How does one become a travel writer? The contrite answer is––travel then write about it, but with a few specific tips to keep in mind.

Take notes

As good as many brains are, none are perfect. The best way to insure your story is as accurate as possible is to take good notes––as you travel. I go so far as to jot down adjectives and general impressions as to not let those memories fade into obscurity.

The hook and introduction

Every story needs a hook, an opening line or paragraph that pulls in the reader and sets the tone for the piece. “Before I could slam my foot on the brakes, the left wheel slipped over the edge, rocks falling a thousand feet to the canyon floor below…” It needn’t be dramatic as in the case of the aforementioned example, but it must be compelling.

With the hook set, the introduction must quickly deliver the reader to the meat of the story and set the stage for events to unfold. These introductions often introduce the reader to the characters, setting, and outline the overall theme of the narrative. Without a good hook and introduction, most readers will never engage the story.

A story versus a journal

The most common pitfall with travel writing is constructing the narrative in strict chronological order. There is an important distinction to be made between a journaling of events and the creative weaving of a story. A story is something you tell around a fire. A journal is probably more fitting for a legal deposition. The “went there, did that” structure gets a tad boring and even predictable. Some stories are best told, or at least introduced, out of timely order. As an editor, I cringe when I read the words, “Day two, we….”

Past and present tense

All too often writers drift in and out of past and present tense. More than just confusing, it makes for a difficult read and can be a deal breaker for publication. While artistic license can accommodate writing in present tense, the best approach is to tell the event as it happened.

The anecdote versus the whole enchilada

If your most recent trip delivered you from one hemisphere to the next over the course of a full year, your story is going to have to incapsulate a specific moment within that journey, unless of course you are writing a book. This is typically how we tell stories around a fire or bellied up to a bar. We cull out the most interesting scenes and expound on them with colorful detail. A retelling of a border crossing or colorful encounter with a local can be far more interesting than a vague accounting of a lap around the globe.

It’s also important to give proper weight to certain story elements over others. It is confusing to the reader to wax poetic for 500 words about your breakfast burrito only to dedicate four lines to seeing Sasquatch board and alien spaceship.

It’s hard to write about the locals if you don’t interact with them. The more you immerse yourself in the culture of a place, the more textured the story will become. Travel in a bubble and the forthcoming story will be reflective of that approach.

Word count

This is less of an artistic consideration than it is a matter of placement and audience. Print features can frequently swell to 3,000 to even 5,000 words. Spanning a dozen pages, a print article can retain a reader’s attention for extended periods of time as they curl up in a comfy chair. Digital publishing appeals to our abbreviated attention spans with most people only dedicating a few minutes to any given article. As such, it is best to keep most web-based stories to 750 words or no more than 2,000. For better or worse, internet stories are best served in small, rich bites.

The visual story

Unless you have an unprecedented command of the written word, your story will only be made better with a catalog of quality images. If a well written story fails to get published, it is almost always due to a lack of good images. We will dedicate an entire feature to this subject alone in the coming weeks, but there are some critical elements to travel photography worthy of mention.

Our esteemed photographer Bruce Dorn offered the best advice, not surprisingly. His top tip is to tell your image story much the way cinematographers tell their stories. A movie scene often starts with a big shot, say of a cowboy riding across an expansive plain. It transitions to a medium shot, of the cowboy faced off for a gunfight. It then zooms in for a tight shot, the sweat rolling down his face.

This holds true for travel imagery. It’s important to capture landscapes, portraits, detailed shots of the food you discover, and if possible the action scenes that give your story a sense of purpose and excitement. The worst thing anyone can do is to only shoot one type of photograph like a hundred wide landscapes, or the most egregious of offenses, a hundred shots of a truck on the side of the road. While it is important to include your truck or motorcycle in a shot or two, they shouldn’t pervade every image. Remember what it is you are trying to convey with your written narrative, and use your images to emphasis that message. If done well, they almost tell the story on their own.

For digital publishing, the most important image is the lead image. As would-be readers surf the web for entertainment, it is the allure of a captivating image, one paired to a catchy title, that compels them to click on a story.

Additional tips

- Unedited works are somewhat expected as writers submit pieces quite literally from the road. It is important however to make a best effort to thoroughly edit your work, or enlist the help of someone you trust to help with those reviews. Mistakes happen, but reducing them should be the goal.

- Not all good reads are the result of perfect writing skills, but it is important to avoid the more common writing gaffs. The over use of exclamation points is particularly ill advised, as is the abundance of unnecessary adjectives. “The very hot sun was assuaged by the extremely cool water beneath the exceptionally tall tree.” Less is more, as they say.

- Once you have your travel opus written and your images compiled, getting them to your proposed destination is important. Be sure to inquire with your intended publication as to how they prefer to receive your text and image files. Every publication is slightly different.

- Become one with rejection or set backs. If your submission fails to meet the publication’s minimum quality standards, don’t get discouraged, get motivated. Make the necessary changes, learn from the process and try again. Where this gets tricky is with image assets. If you only captured sub-par images of your trip, nothing is going to make those images better.

The Content Submission Process

There is a somewhat standardized process for submitting editorial works to print and digital publications.

- The query: A query is the preliminary proposal of submission. Writers will send a query to editors pitching a particular work. That editorial may be fully completed, or most often, slated for future completion. A query usually includes a synopsis of the editorial, a sample catalogue of images, and on occasion a sample of the author’s writing. Once a query has been accepted, the editor moves the project to the next phase.

- Once the submission query has been accepted and the editor has informed the author of desired word count and image standards, a deadline will be set and other details of the agreement are discussed.

- At this time, the editor may submit a document to the author with formal “Writer’s Guidelines.” This is a document outlining the editorial standards and expectations of the publication. It will also include instructions for sending the text and image documents to the editor.

- At this time the completed work is submitted per the editor’s instructions and reviewed. It is possible the editor may require rewrites at this time. Although not common, the piece may also be rejected if it doesn’t meet the editor’s expectations, although rewrites typically resolve any initial concerns.

- The piece goes to print and the author is made world famous.

If you have a story you would like to have published on Expedition Portal or within the pages of Overland Journal, submit your query to: christophe@overlandinternational.com

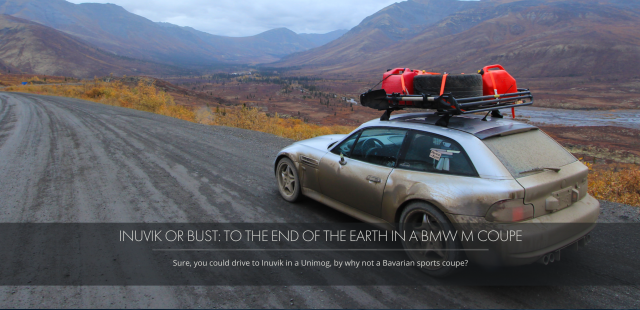

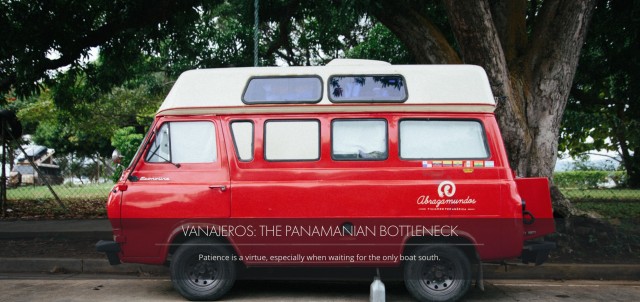

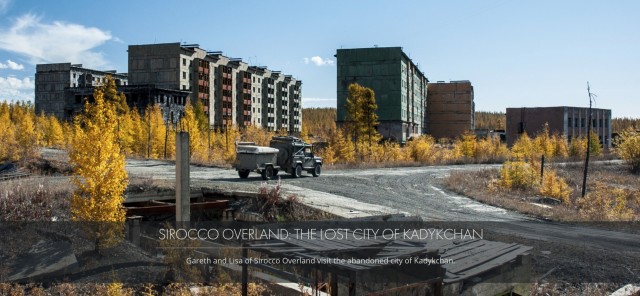

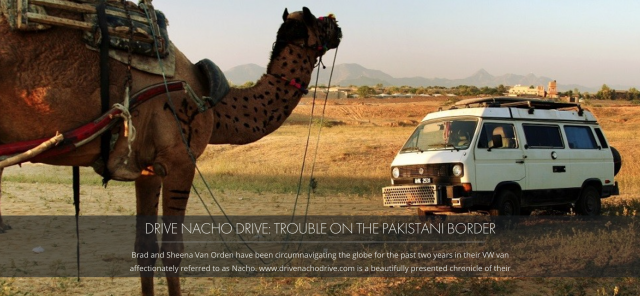

Our favorite stories of the year [Click on the image]

Over the last year we’ve had the good fortune to feature works from a variety of talented travel writers. Their adventures, and the stories that came of them, are tremendous examples of why the process of sharing is so valued. Note the captivating lead images.