It was a hot, muggy night in early 2019. We had driven most of the day on terrible, muddy tracks and arrived in a small Gabonese town just before sunset. The air was thick with smoke, as much of the local economy seemed dedicated to turning healthy trees into charcoal, alongside the extraction of palm oil.

Gabon is not a country known for an abundance of campsites, and we were forced—common practice in West Africa—to ask the local gas station attendant if we could camp overnight on the premises. After purchasing a full tank of fuel and tipping generously, we were given permission.

The forecourt of the gas station we found that night was large, quite modern, and well-lit. A generator hummed behind the store where we bought refreshments. I settled down to rest after the day’s drive while Luisa and the children prepared a simple dinner: pasta with onions, peppers, and tomatoes.

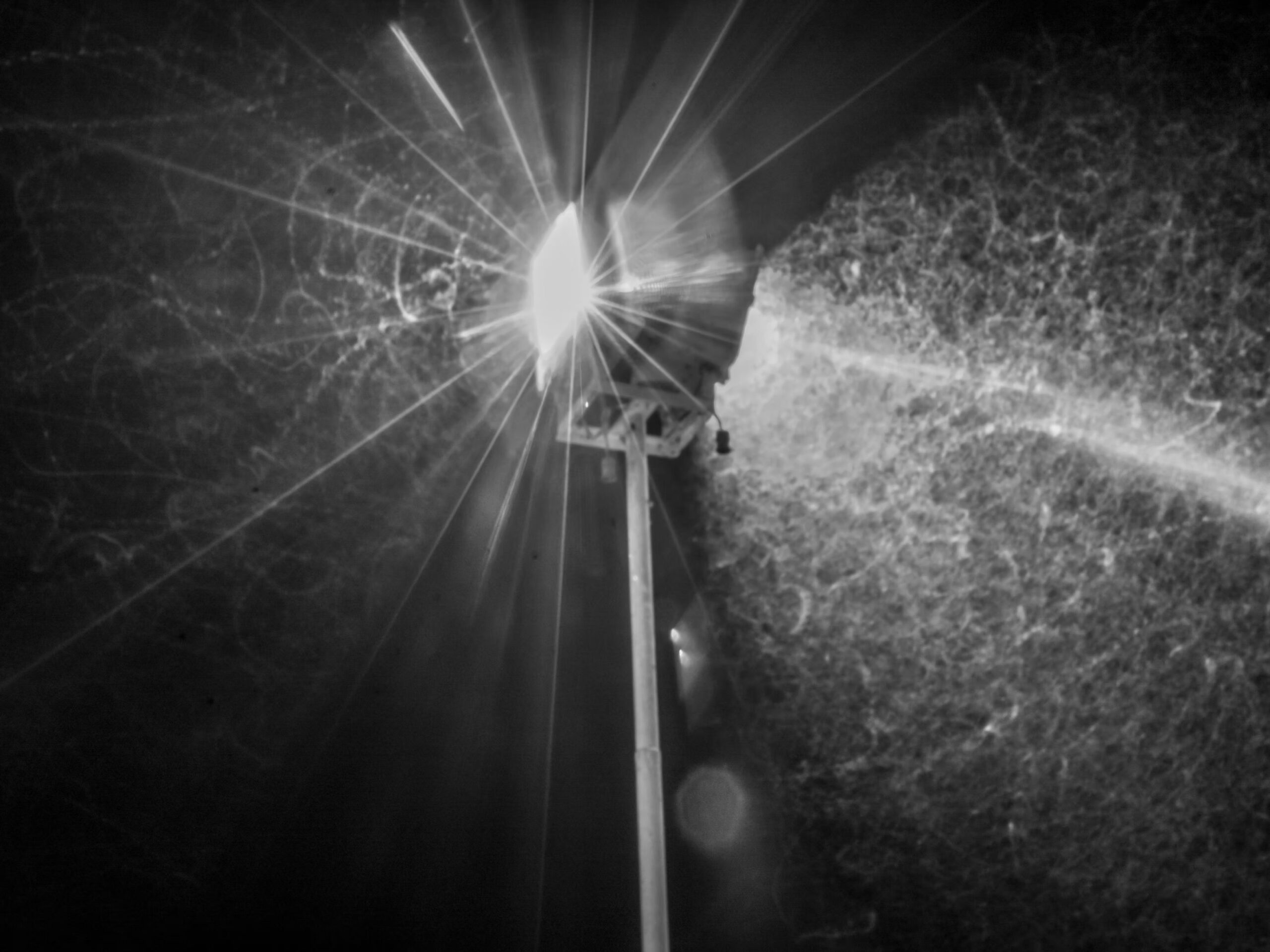

I sat back in my chair and enjoyed the sunset, occasionally glancing up at the large security lights that flooded the forecourt. As I watched, a swarm of insects gathered around the lamps, hypnotized by the bright white glare. Before long, the sky turned velvet black, and the lights drew in even more bugs, creating a feeding frenzy as smaller insects arrived only to meet their end.

Because it was so hot in the camper—the water boiling, the occupants sweating, and the insects seemingly preoccupied—Luisa opened all the window netting in an attempt to catch even the slightest breeze.

And then, catastrophe. The generator hiccuped and stalled. The lights died instantly, and suddenly, the only lights in that stretch outside town were ours. The swarm surged toward the Defender and invaded our small home—millions of them, large and small. With Luisa and the kids screaming, swatting at the bugs, and slamming the windows closed, the insects occupied every space. They filled our dinner pot, climbed into our pillows, and scratched at the family’s skin.

I sat in my chair, completely unmolested, chuckling, aware that no harm would come to the family despite their panic. “Turn off the lights,” I instructed. The family flailed, swatted, and screamed in frustration. “Turn off the lights!” I shouted. “Turn off the bloody lights!” The insects were crawling in through the window frames.

I grabbed a flashlight, set it on the hood of an old Peugeot station wagon parked behind the Land Rover, and switched it on. Then I shouted again for Luisa to turn off the interior lights. Eventually, she fought through the panic and did so. Predictably, the swarm flocked to the new light source. Five minutes later, the generator spluttered back into life, the forecourt lights returned, and the frenzied bugs lifted back into the night sky. We learned a valuable lesson that day. And we adopted a pregnant praying mantis, who stayed with us all the way to Ghana.

When planning campsite lighting, keep these principles in mind: Equip yourself for function, not excess. Use only as much light as you need. Ensure your lighting stays within your own site, does not spill out, and is gentle on the surrounding environment and fellow campers.

Camping is about stepping away from artificial light. It allows your eyes to adjust to darkness, appreciate the night sky, and reduce light pollution. Excessive lighting ruins that experience for everyone. High-output lights have their place: for cooking, organizing gear, finding a wandering dog, or watching children. Even then, keep them task-specific, angled downward, and shielded. After dinner, once camp settles, there is little reason for broad floodlighting.

Light discipline should be common sense, yet it is often overlooked. We have camped in countries everywhere—from remote backcountry locales to high-end campgrounds, and yes, even fuel stations. We can sleep through most disturbances, but not sustained floodlights. Harsh white beams easily penetrate tent mesh, thin camper curtains, and RV window coverings. Poorly considered lighting affects others more than many realize.

What Lighting Works Best in Different Scenarios

Our friend Jon, a lighting engineer, insists on camping with a red light, whether outdoors or while socializing inside the camper. I’ll admit I’m not naturally drawn to the red hue, especially inside a camper. However, we now run colored LED lights underneath our vehicle (what we jokingly call our “pool lights”) for both function and aesthetics.

Red light attracts fewer insects than white or blue light. Many nocturnal insects are most responsive to ultraviolet, blue, and green wavelengths, which they use to assist with navigation and foraging. Because insects are far less sensitive to longer wavelengths—such as red and amber—these colors are generally less attractive. Red light does not repel insects, but it is significantly less visible and less appealing to many species compared to shorter-wavelength light. Red light also preserves human night vision. Transitioning from artificial light to darkness relies on rod cells in the retina, which are less sensitive to red wavelengths. Red light does not disrupt dark adaptation as much as blue or white light, allowing your eyes to recover faster. That is why most headlamps include a red-light option. Simply put: white light resets your night vision; red light helps preserve it.

Green light enhances terrain visibility and contrast at night. The human eye is very sensitive to green, especially in low light. Green lighting gives strong visibility but is gentler on the eyes. It is common in hunting and tactical navigation, where accuracy counts, and harsh brightness does not.

White light is best when you need maximum visibility around camp. However, it disrupts both human and wildlife vision and attracts significantly more insects. Warm white light is easier on the eyes, preserves night adaptation more effectively than cool white, and creates a more natural and relaxed atmosphere. Cool white helps you see; warm white helps you relax—and your body and the environment respond differently to each.

When lighting is labeled 2700K or 5000K, the “K” stands for kelvin, which measures color temperature—the appearance of light ranging from warm (yellowish) to cool (bluish)—and not brightness.

1800-2200K – Deep amber, mimicking candlelight or campfire glow

2200-3000K – Warm white, such as soft, residential lighting

3500-4000K – Neutral white (clean but not harsh)

5000-6500K – Daylight/bright white

The lower the kelvin number, the warmer and more amber the light. The higher the number, the cooler and bluer the light becomes. In practice, most expedition travelers find 2200K-3000K ideal for general camp ambiance and 4000K-5000K appropriate for task lighting such as food preparation or mechanical work.

Power Sources

There will never be a perfect light. Each traveler has preferences, but the following considerations are worth evaluating when selecting a power source.

Gas is a viable option in remote areas without electricity. A small green propane canister can power a lantern for several hours. However, they take up space, require refilling or replacement (which is not environmentally friendly), and raise concerns about emissions regulations in some regions. There is also the risk of carbon monoxide poisoning in enclosed areas, as well as the hazard of being knocked over by small children or enthusiastic pets.

Solar lights work well in sunny climates and are safer for tents, though performance drops during extended periods of cloud coverage. Many options now include USB charging to enhance versatility.

Hand-cranked options are excellent in emergencies—and children love to “wind them up.” They are typically durable but require physical effort and offer limited runtime per crank. Without a minion on duty, you may be the one doing the cranking.

Battery-powered choices are easy to use and widely available, keeping in mind that disposable batteries require ongoing replacement and proper disposal. Rechargeables are preferable, but quality matters—cheaper cells degrade quickly and become a false economy. Battery-powered lights often provide more consistent, higher output than small solar units.

Different Lighting for Different Users

Hikers

When hiking, you cannot afford to juggle a flashlight while you navigate uneven terrain. A head torch is essential: lightweight, bright, and hands-free. Modifiable brightness saves battery life and responds to varying trail conditions. Low-lumen settings are also ideal inside a tent. Hikers need efficiency.

Campers

Stationary campers want comfort and function. Awning lights, lanterns, and string lights give ambient light for cooking, dining, and socializing without dominating the space. You can put lanterns on tables or hang them in tents. A headlamp or handheld light is useful for bathroom trips.

Overlanders

Overlanders combine mobility and extended stays, requiring lighting that integrates with the vehicle and campsite. Awning and fairy lights define your immediate campsite and contribute to a pleasant mood. When we camp for more than a few days in one place, we like to set up the string lights to make our camp more homey. Lanterns provide safety around your vehicle. Interior lights often spill outward for convenience, but they also attract insects. A head torch is important for hands-free tasks or repairs. Undercarriage lighting—our so-called pool lights—looks good and is practical in places with scorpions or snakes.

Groups and Families

In group settings, especially with children, visibility prevents collisions and confusion. Assigning each person a light source reduces risk. Glow sticks, clip-on LEDs, and even light-up shoes (yes, the silliest options often work best) provide passive visibility without constant torch use.

Weatherproof, Waterproof, and Submersible

Every overlander eventually experiences an abrupt weather shift—from clear skies to heavy rain—at precisely the moment lighting is most needed. It’s not an ideal situation when Mother Nature is your only source of illumination.

Weatherproof does not mean waterproof; it typically means resistance to light splashes, humidity, and dust exposure—not sustained rain. An IPX4 rating, for example, protects against splashing water but not submersion; specifically, IPX4 is a water-resistance standard indicating protection against water sprayed from any direction, but it does not guarantee protection from immersion.

IP ratings are defined by the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) Ingress Protection (IP) classification system. The first digit (0-6) indicates the level of protection against solid objects like dust, and the second digit (0-9) for protection against liquids, such as water. For example, IP67 means the device is completely dust-tight (6) and protected against temporary immersion in water (7). When you see “IPX,” the “X” means the device was not tested for dust resistance—it does not mean extra protection.

Waterproof ratings generally start at IP65. Exterior-mounted vehicle lights should ideally be rated IP67 or higher, especially in wet or snowy climates.

Submersible equipment is typically rated IP68 or higher, meaning it is dust-tight and capable of surviving immersion at the manufacturer-specified depth. Think action camera—but as a light, suitable for river crossings, muddy trails, and marine activities such as kayaking or diving.

Portability and Ease of Use

We traveled for years with collapsible Luno lights. They were extremely popular, but once damaged, they were difficult to repair, leaving you with a pile of plastic waste. And you rarely carried just one. Collapsing and reinflating daily would have been tedious had I not had young assistants keen to “help.” For hikers or backpackers, however, they are still a viable option and can even be left outside as a mild deterrent.

Roll-up spool designs significantly improve portability and storage capacity while maintaining multi-use functionality. This format is common across several lighting categories, including fairy light spools, retractable LED rope lights, integrated magnetic campsite string lights, and solar-powered spool systems.

We were once gifted a Milwaukee head torch with an integrated battery bank. Was it practical? Yes. Comfortable? Not particularly. After an evening outdoors, the weight became noticeable.

Lighting should be intuitive, accessible, and quick to deploy.

Emergency Lighting Options

On the road or trail, emergencies often occur after dark. A vehicle breakdown, severe weather, or a power outage quickly transforms inconvenience into vulnerability. Reliable emergency lighting is essential.

Prepared communities emphasize redundancy: multiple light types for multiple scenarios. Our kit includes road flare lights for breakdowns, head torches for everyday use, a magnetic light bar for vehicle mounting (our Land Rover’s aluminum body panels make that an interesting exercise), under-vehicle “pool lights,” fairy lights for ambience, and blue light use in desert environments to avoid stepping on something unpleasant. We maintain a dedicated storage area in the vehicle for lighting solutions covering every contingency. Now to get a flare gun.

Mindful lighting is less about lumens and more about restraint, integration, and respect—for the environment, for other travelers, and for the experience that drew us outdoors in the first place. We leave cities to escape artificial light. It would be ironic to recreate them under canvas.

Read More: Buyers Guide :: Pop-top and Expandable Living

Our No Compromise Clause: We do not accept advertorial content or allow advertising to influence our coverage, and our contributors are guaranteed editorial independence. Overland International may earn a small commission from affiliate links included in this article. We appreciate your support.