Photos by Eva Rupert and Bill Dragoo

Traveling by motorcycle during the summer months is a game of chance for those of us who live in the desert. The days are hot, and the storms seem to come out of nowhere. We plot our routes through the high country whenever possible, pack our rain gear at the top of our panniers, and hope that Lady Luck dons her helmet to ride along pillion. I had 10 days to complete a four-day trip. Why rush when time was on my side?

I rode north out of town through the cool afternoon air, a welcome relief courtesy of the Southern Arizona monsoon season. Storm clouds piled up in the gray sky, but Bisbee’s canyon walls kept them at bay. I was heading to Oregon to explore the American West and put some proper backcountry miles on my freshly minted Yamaha Ténéré 700, a motorcycle I’d had the pleasure of spec-ing out with my every ADV desire. This ride, free from workaday routines and cell service, was to be the reward for all the sweat, time, and twisting of Torx bits I poured into the build.

My first waypoint of the trip was Clifton, a seen-better-days mining town at the southern terminus of Highway 191. Also known as the Coronado Trail National Scenic Byway, it is easily the best stretch of tarmac in Arizona, boasting 460 curves and topping over 9,000 feet in elevation.

The road is just how I like my pavement: incredibly scenic, light on traffic, with no gas stops to interrupt the flow for over a hundred miles. The awe factor kicked in promptly as the byway took me directly through the Morenci Mine. Surrounded by slag piles as big as mountains, the enormous open-pit copper mine is one of the largest in North America. It takes a full 20 minutes to ride through it, and from across the expanse, mining trucks look like Tonka toys as they haul their huge loads out for processing. The sheer size of the pit is breathtaking, and I decided to camp a hair north of the mine to save the best of Highway 191’s twisties for my second day out. The smell of far-off monsoons blended with the butterscotch sweetness of ponderosa pines, scenting my campsite as I settled in for the night.

I woke up the next day with an agenda to meet my soon-to-be riding buddy, Bill Dragoo, in La Sal, Utah. Bill was heading west out of Colorado, and we were linking up at 3 Step Hideaway, an off-grid bed and breakfast that caters to adventure motorcyclists. I promised to be there in time for dinner.

I love traveling alone, but I invited Bill to join me at the last minute. Perhaps, when I sent that text, I was thinking that I had dropped my GS one too many times in the Baja sand the previous winter. I remembered cursing the thing back upright, promising myself that I would take a dang motorcycle class one of these days. In addition to hopefully being good company on the trip, I knew that Bill is a top-notch off-road motorcycle trainer and owner of DART (Dragoo Adventure Rider Training). I suspected I could learn a thing or two from him if he joined me.

Fueled with two cups of coffee for breakfast and with 400 miles to get to the lodge, it seemed reasonable to make sure the Ténéré knew that every turn of Highway 191 was to be taken at the maximum safe velocity. Throttling up the twisting pavement, the bike was eager to oblige, only occasionally reminding me of its 21-inch front wheel and knobby Battlax tires as I carved my way through the serpentine tarmac and gorgeous scenery of the Apache-Sitgreaves National Forest.

Eventually, the Coronado Trail National Scenic Byway came to an end in Springerville, Arizona, but not before taking my breath away and recalibrating my soul with the high-elevation air and the frequency of its flowing curves. Continuing north, Highway 191 flattened out, losing some of its alpine luster but still scrawling a lovely ribbon across the Colorado Plateau.

I thought I was making good time through the Four Corners into Utah, but realized after looking at my phone that the Daylight Savings Time debacle had gotten the best of me. In Arizona, unlike those in the less-fortunate states surrounding us, we don’t set our clocks ahead in the summer. Entering Utah, I knew I would be an hour late for dinner and worried that Bill would be waiting on me.

Exiting the tarmac, I scrambled down the last half mile of groomed gravel and suddenly felt like I had slipped through a time warp. Tipis, cabins, and an Old-West-style cantina cast shade for me to park under. Had I not seen Bill’s BMW sitting beside one of the cabins, I’d have sworn I had stepped back into the 1800s. Only the 21st-century greenhouse and spotless stainless steel outdoor kitchen contrasted with the vintage vibe I had entered.

I parked my bike in front of the cantina at 3 Step Hideaway with a litany of apologies at the ready. Pushing open the saloon door, I rolled into a round of hellos and hugs so hearty, no reparations were necessary. Bill had been swapping stories with Scott and Julie, the owners of the lodge and Arizona transplants who had probably also forgotten about daylight savings at one point in time.

Our dinner consisted of steaks, grilled to medium-rare perfection by Scott, and a spread of Julie’s side dishes that surely had mouths watering clear to Moab. After dinner and discussing the finer things in life, like dirt roads and the rainy season in the West, Bill and I set our sights on the route ahead.

A proper adventure ride should allow triple the required time and twice the minimum mileage to get to any destination. We had a week and a half, more than enough time to get to Oregon, but with so much incredible riding packed into one state, it was hard to fathom how we would ever make it out of Utah.

The next morning’s sunrise lit the La Sal mesas in every imaginable shade of gold and copper. Over coffee, Scott gave me a tour of the buildings and greenhouse, each a testament to his craftsmanship and Julie’s gardening prowess. The property consists of several lovingly restored buildings that serve as cabins for guests, an outdoor kitchen, and a bathhouse complete with an outdoor hot tub for cleaning up and relaxing after a long ride. Between the cabins, tipis, tent sites, chickens, and gracious hospitality, it was almost a shame to plug Hanksville into the GPS and say goodbye to our hosts.

Heading south through the Manti-La Sal Forest was far from the fastest way to the Pacific Northwest, but it would allow us to carve our way through some lovely country. With zero regrets, we paid homage to the asphalt gods by sacrificing a bit of knobby tread on Highway 95, crossing both the Canyonlands and Capitol Reef national parks. We then jogged onto Highway 50, dubbed the Loneliest Road in America, making a beeline for Nevada. Soaking up Utah’s incredible scenery at highway speeds may not be as glamorous as going at it in the dirt, but we played our cards well to make some miles on our way to Oregon, savoring the more technical off-road portion for later.

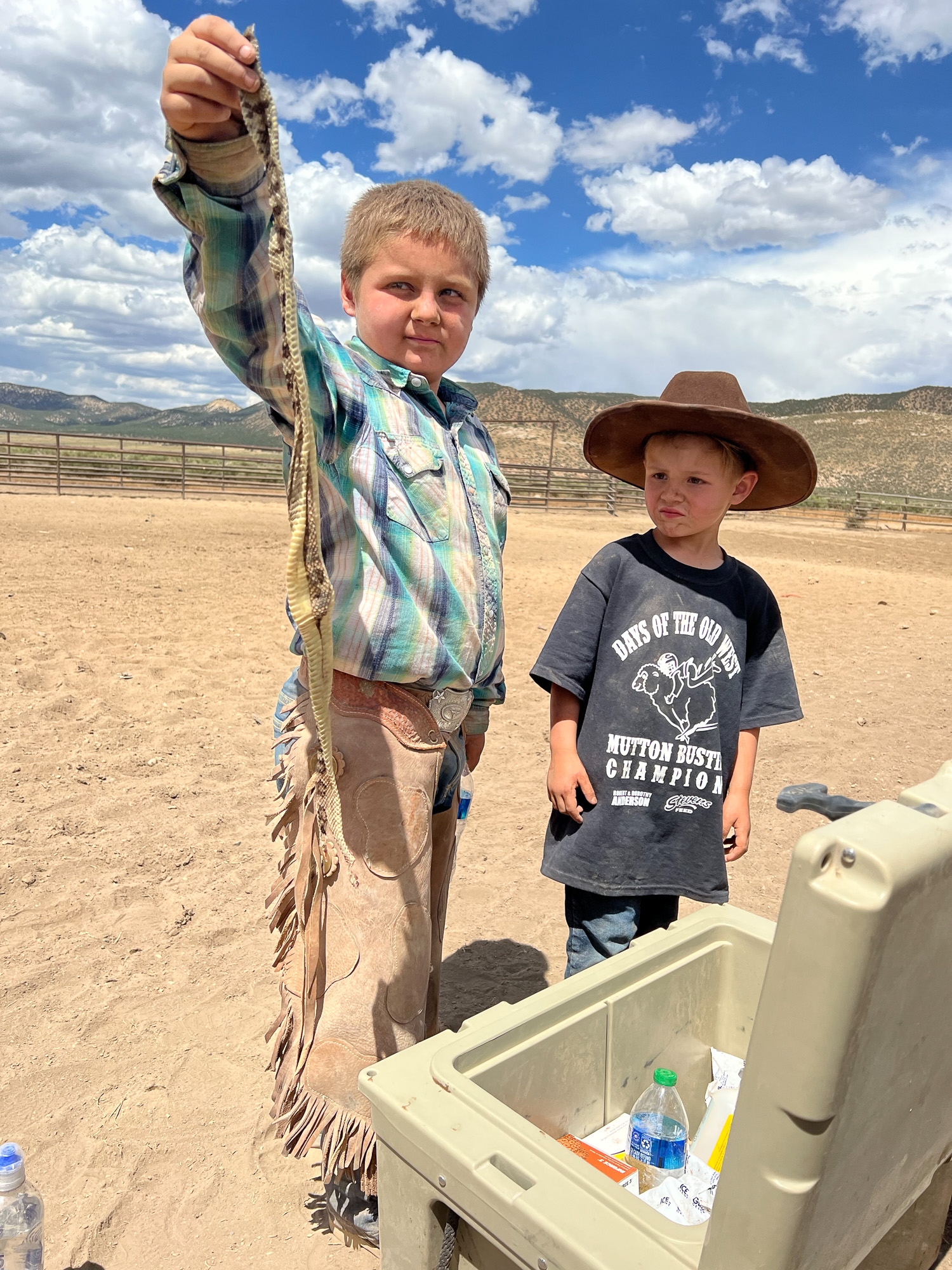

Closing in on the Nevada border, a cloud of dust rose up behind a cattle fence and caught our attention. Leaving the highway, we rode gingerly up to a large wooden corral flanked by a half-dozen horse trailers. We approached slowly with smiles and a wave that I hoped would convey our friendly intentions as the leery cowboys eyed our iron horses. I barely had my helmet off before being surrounded by a posse of dusty kids dressed like the ranchers in chaps and hats, brought along by their parents to learn the art of cattle branding. “Do you want to see the rattlesnake we got today?” the oldest boy asked, already pulling the snakeskin out of a cooler. “Look! We caught it over here! It was right under that rock! Are those your motorcycles? Wow, cool!”

.

Kids are always the best ambassadors and have a way of spanning the distance between strangers. The ranchers warmed up to us as their children extended the olive branch with their curiosity and questions. They swarmed our motorcycles, regaled us with stories and cookies, and gave us a glimpse into a corner of their world. There, by the corral, we traded enthusiasm for each other’s way of life, as often happens when cultures cross paths.

Newel, the ranch manager, told us that this was the last day of branding for the season. “It was an easy day, just a couple hundred,” he said. They had branded four thousand cows in the few days prior. As we said our goodbyes, he sent us off with the kind of blessing only a rancher from the arid Great Basin could sling with such sincerity, “I hope it rains on you all the way to Ely.”

In the near-hundred-degree heat, his blessing was well taken. Promising to keep in touch with the branding crew and the kids, we set off toward the state line. On cue, the clouds piled up, and a drizzle became a downpour. Per Newell’s blessing, we reveled in the refreshing ride until we reached Nevada.

With the summer rains, the smell of sage was a constant backdrop for our trip. There are six subspecies of Artemisia tridentata that are officially recognized by the National Plant Data Center, and I have no doubt we inhaled some of each—the official aroma of the high-desert monsoon season—as we made our way across the West. The silvery scent filled my helmet on the highway and fanned from our panniers as we brushed along the trails, wafting through the mesh of our tents as sunsets melted into the desert skyline.

We finally got our treads into proper dirt on the northern sections of the Nevada Backcountry Discovery Route (NVBDR). From Austin to the Idaho border, the NVBDR offers everything from ripping fast gravel to forest roads rife with scenery. In addition to the main route, the detours we took were equally impressive. Each out-and-back we explored led to a basin of wildflowers or a unique view of the Jarbidge Mountains.

At one point, I dropped my bike at the bottom of a long section of rocky two-track. To save face in the presence of my pro-status riding partner, I rushed to right the loaded Ténéré before Bill could get his kickstand down to help. A few miles later, even Bill chose a bad line and dumped his BMW in a heap of rocks. He graciously accepted my help to get him back upright, and I’ll go to my grave swearing he did that on purpose, just to make me feel better.

Following Bill along a single-track spur, he must have seen me fighting the rut in his rearview mirror. Kicking into his off-road instructor mode, he said, “If you are riding in ruts, make the rut your road,” a phrase he has undoubtedly shared with students a thousand times before. “Keep your eyes up, arms loose, and steer with your feet.”

I relaxed my grip on the Ténéré’s handlebars, and the bike tracked effortlessly along the trail with gentle input on the foot pegs. To my delight, Bill peppered training tips throughout the ride, each one grounded and practical but delivered with a catchphrase that makes them stick to your ribs. Shifting your weight in counterbalanced turns becomes doing the Hokey Pokey. He calls managing clutch and throttle in a properly executed loose hill start “making brownies.” As in, tractoring up loose hills without spinning your wheel leaves tidy imprints from your knobby tire treads, like a pan of sliced brownies.

By reputation, I knew that Bill would be a good rider and coach, but I was delighted to learn that he was also a good traveler, which is an entirely different skill set altogether. Traveling well requires as much grace as it does stamina. We must be level-headed when the going gets tough and should deliberately maintain a sense of curiosity to truly appreciate the world around us in real-time. Everything from the route to the weather to the decisions we make affects our travels for better or worse. The greatest variable of all is often the company we keep on the road, and I felt fortunate for this entire journey.

In addition to the easy camaraderie and riding lessons, I was particularly thrilled to learn that Bill shares my habit of talking to strangers. We stopped along the roadside to chat with hikers and cyclists making their pilgrimages across the West; we lingered outside convenience stores to hear the stories of peoples’ travels and answer their questions about ours. Back on Highway 50, before hitting the rougher dirt, we stopped to check on a man pushing a bicycle and trailer. Mark, it turns out, lives on the road, coaxing his rickety old bicycle with all his worldly possessions along at a snail’s pace wherever his whims might take him. We resupplied his sparse rations of water and food before saying our goodbyes. With every traveler we met, an unspoken fellowship underscored our conversations, encouraging us to keep the pace slow and smell the flowers, or sage, as it were.

Bill and I stuck to the dirt for the remainder of the trip, touching pavement only when we needed gas or to connect the dirt roads. We made our way off the Nevada BDR along Gold Creek Road through Humboldt-Toiyabe National Forest. Cutting north into Idaho, we ripped along the 100-mile Owyhee Backcountry Byway, spitting gravel toward the state line. We smashed a few thousand Mormon crickets as we crossed their infestations and were forced once to get hotel rooms rather than camp in their midst. Continuing into Oregon, we traipsed through a lava field on the edge of Steens Mountain, dodging jagged rocks in the midst of otherworldly beauty.

Early in the trip, I had promised Bill a dinner of Jetboil pad thai, one of my backcountry specialties. On that final evening by the Steens Mountains, I cooked a pot of spicy peanut sauce and rice noodles. Before climbing into our tents that night, Bill produced a copy of Peter Egan’s book, Leanings 3, and read a few stories aloud as we sipped bourbon. What better way to end a motorcycle adventure?

For the sake of storytelling, I almost wish I could share examples of mishaps, things that went wrong, or troubles overcome. But each day was filled with fantastic riding, and our evenings were spent kicking back in wild, dispersed campsites. All across the West, we pitched our tents by remote lakes and on hidden hillsides overlooking landscapes that could grace the cover of a Western States guidebook.

Despite a deliberately rambling pace, all too soon, it was time for Bill and me to part ways. We managed to take more than a week to cover three days of distance. My skills had grown, as had our friendship. It was abundantly clear that Lady Luck had, in fact, donned her helmet and packed her panniers to ride alongside us—all the way to Oregon.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in Overland Journal’s Winter 2023 Issue.

Read more: Eva Rupert :: Modern Explorer

Our No Compromise Clause: We do not accept advertorial content or allow advertising to influence our coverage, and our contributors are guaranteed editorial independence. Overland International may earn a small commission from affiliate links included in this article. We appreciate your support.