Thirty-six Hours of Adventure :: The Olympic Peninsula

Presented by ARB USA

One of the great joys of traveling in the continental United States is the fantastic diversity within our borders, the transition from the densely populated and wooded Northeast to the arid and mountainous Southwest. Within a few days’ drive, we can shift climates, microcultures, dialects, and even language without dusting off the passport. It is little wonder that less than 42 percent of Americans have a passport—so much can be experienced close to home.

For this adventure, I hopped on a plane from Prescott, Arizona, and migrated my way north to Seattle, the entire contents of my travel kit confined to a few carry-on bags. Short of a knife (for obvious reasons), I had everything I needed, including a pillow, a down sleeping bag, headlamp, and even a proper camera. In recent months, I have been experimenting more with minimalist travel, which has been quite the journey itself, and a lesson in just how easy it is to wash clothes in the bathroom sink. This effort also increased my interest in flying and driving, so long as the awaiting vehicle has some basic considerations for backcountry exploration.

Touching down in Seattle, I picked up a modified JL Wrangler and prepared for a long weekend in the field. The Jeep was well suited to travel with an ARB roof tent, fridge, full recovery kit, and necessary tools. The vehicle was spotless, but the first rule of flying in and driving is to do a complete inspection of the loaner vehicle, even if it is fresh off the Hertz lot (or from a manufacturer as in this case).

Seattle traffic is notorious, and I experienced some of the worst of it while navigating towards the Peninsula. My trip also included a lunch break at the John Wayne Marina, a picturesque spot en route to Neah Bay.

The first challenge for the trip was to navigate the traffic, accidents, and general immensity of Seattle rush hour traffic, the JL proving to be far more comfortable and easier to pilot than the 3-inch lift and 37-inch tires would have predicted. Getting out of the city also proved just how fractured the landscape of the Seattle area is, as there are few straight lines between any destination. I needed to go waaay south to go back north.

This is a wild and unforgiving coast, but the remoteness provides rare access to park and even camp in designated areas like this one.

Making Camp and Discovering Relics

In today’s #vanlife world, finding a place to camp is a bit more complicated than it used to be. Pulloffs are now often signed with “no camping,” and available spaces are clogged with Sprinters, E350s, and vintage wagons. No negative judgment there, but it is a reason to have a more capable vehicle, which allowed me to leave the beaten path and venture into the rain forest south of the Salish Sea, an intricate maze of secondary roads, two tracks, and hiking paths.

I pushed deeper into the 4WD roads north of the Strait of Juan de Fuca (Highway 112) and found a muddy and technical trail that cut off into the direction of the sea. Though I was hoping to find an overlook onto the beach, the trail quickly degraded into a muddy mess, with several large mounds and deep ruts. I engaged low range and eased the front of the Wrangler over the obstacle, expecting it to ground hard on the skid plate. It did, and the tires started to spin slightly. Applying the brakes and stopping the spinning wheels, I engaged the Air Lockers and began feeding throttle, which allowed the left front tire to find some traction and pull the chassis forward just enough for the other tires to hook up. There is a reason why Jeeps are often the weapon of choice for trails like this. After driving through deep ruts and a small water crossing, the track ended in a large cleared area that was reasonably flat and perfect for popping up the roof tent.

I explored the area well into the night, and was grateful for the notable output of the LED driving lights.

I have learned a few tricks along the way for setting up RTTs on tall SUVs, including relying on the rear tires as a step to access zippers and the vinyl cover. Within a few minutes, the Simpson III tent was set and ready to be my tree fort for the night. As it was already dark, I retired to the comfort of my perch and continued listening to my audiobook from the day, the excellent Vagabonding by Rolf Potts. With thoughts of distant lands and exotic cultures filling my mind, I drifted off for the night. But in typical Washington fashion, I woke to the pounding of rain against (what seemed like) every side of the tent. I grabbed my flashlight and searched for leaks (a lesson I learned the hard way with lesser quality RTTs), yet found none. The rain remained steady, interrupted by louder drops that had collected and dropped from the trees above. I can generally sleep through anything, but my life in Arizona has certainly made those sounds foreign.

Admittedly, I slept in later than normal, partly due to my lack of sleep during the night, but also the prospect of putting the tent away in the rain. Eventually, the downpour turned to a sprinkle, and I ventured into the daylight. It was also time to get some exercise in, which I like to do most mornings, and have always found possible, even when traveling. I headed down the trail that departed toward the coast from my camp. Within 20 yards, a dark hole caught my peripheral vision, and I turned to see an open door beneath an earthen mound, not 5 feet from the path. I stood there for a moment, completely surprised, both because of the bizarre discovery, but also because this was within a stone’s throw from where I had slept.

I walked closer, my eyes adjusting to the dark recesses, words taking shape from years of graffiti on the walls. I suspected it was empty—hoped it was empty. And being the adventurous sort, I continued inside and found an entire facility under the ground. Several rooms and halls were still in near perfect condition, and my imagination meandered toward the TV show “Lost” and the Dharma Initiative. As I moved into the larger room, the structure’s intention became clear—a narrow open portal facing the sea. This was a gunnery bunker, which I assumed was made during WWII to defend this remote coastline and the waterway leading to Seattle. Research after the fact has revealed some incredible details on this bunker and other installations like it. I was so excited by my discovery, I completely forgot about the hike and spent nearly an hour photographing and otherwise documenting the structure. It also served as a reminder to get away from the vehicle and hike around—you never know what you might find.

I walked closer, my eyes adjusting to the dark recesses, words taking shape from years of graffiti on the walls. I suspected it was empty—hoped it was empty. And being the adventurous sort, I continued inside and found an entire facility under the ground. Several rooms and halls were still in near perfect condition, and my imagination meandered toward the TV show “Lost” and the Dharma Initiative. As I moved into the larger room, the structure’s intention became clear—a narrow open portal facing the sea. This was a gunnery bunker, which I assumed was made during WWII to defend this remote coastline and the waterway leading to Seattle. Research after the fact has revealed some incredible details on this bunker and other installations like it. I was so excited by my discovery, I completely forgot about the hike and spent nearly an hour photographing and otherwise documenting the structure. It also served as a reminder to get away from the vehicle and hike around—you never know what you might find.

Walking Among the Ancients

The road west continued towards Neah Bay, and the home of the Makah, a tribe of Native Americans. The Makah are indigenous to this area, their original territory comprising an area 300,000 acres larger than their lands today. Traditionally, they were a very successful tribe, often having more food than they could eat, giving them the reputation of “people generous with food,” which is how their name originated.

Neah Bay is a beautiful spot, complete with accommodations and cafes.

No visit to this region is complete without exploring the renowned museum at the Makah Cultural and Research Center, a facility with extensive artifacts on display, many recovered in the 1970s during an archaeological dig along the coast. The project uncovered extensive permanent camps with longhouses up to 70 feet long. The tribe members were highly skilled mariners, capable of navigating and fishing in the open ocean using canoes. There is even evidence of sails used to take advantage of the winds in the Strait of Juan de Fuca, and extensive fishing nets that predate European arrival. I was not only moved by the museum but impressed by how prolific and successful the Makah were.

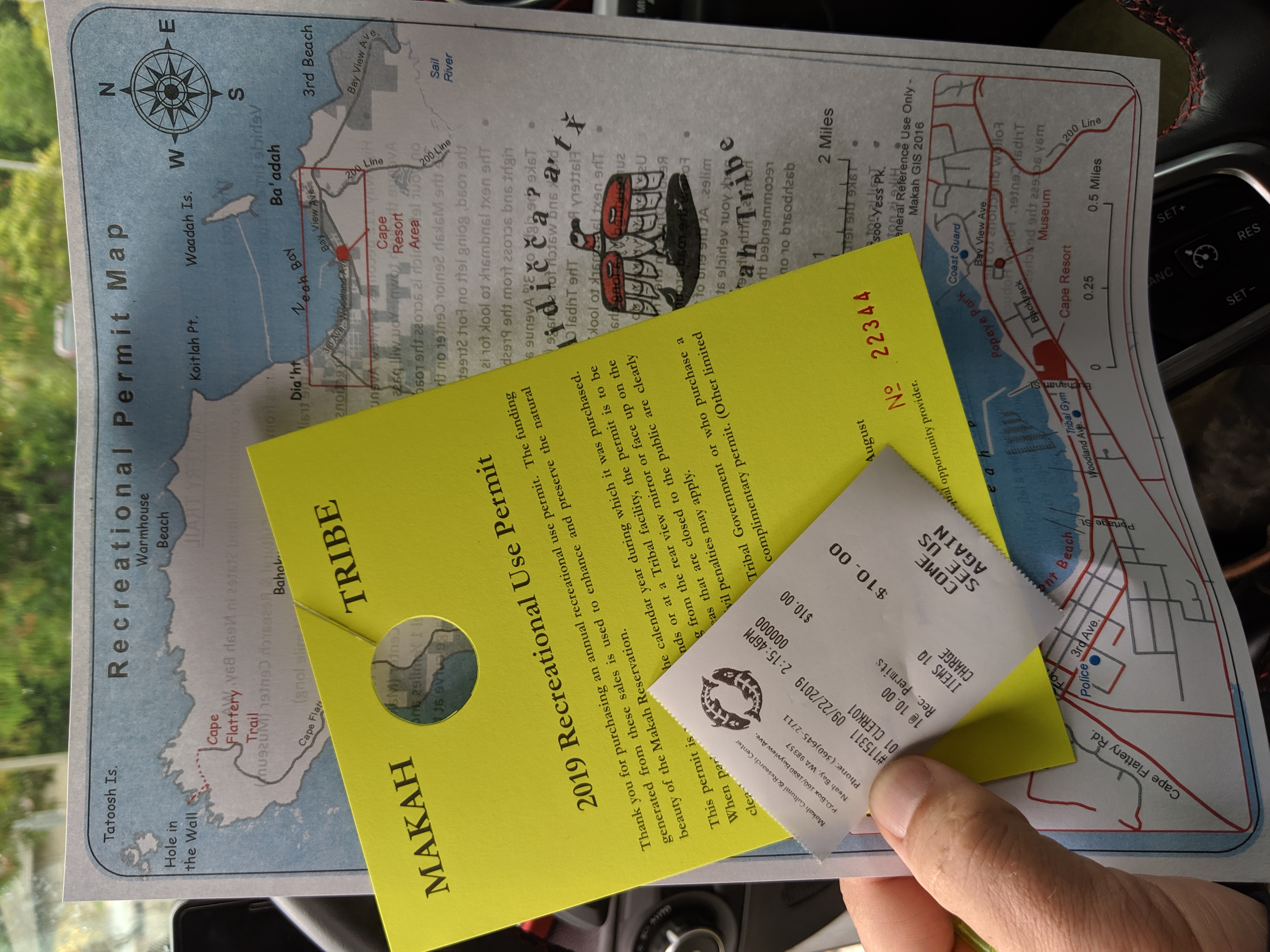

Remember to purchase a recreational use permit for your visit to the Makah Tribe. It is only $10 and goes to help the community maintain their lands and heritage.

Continuing to the west, I took the Cape Loop Road toward Waatch and Cape Flattery. The route is stunning with massive stands of Sitka spruce and thick, lush groundcover. There is a small parking area near the cape that allows access to a hiking trail a little under a mile long. I took my time enjoying the walk, which includes long sections of raised wood planking and several viewing platforms. This provides access to the northwesternmost point of the 48 states and an expansive view into the Pacific Ocean.

From the parking area, there is a graded dirt road that continues north into the forest, and also allows for additional 4WD exploration. The northernmost track degrades into a Jeep trail and terminates near a waterfall. I spent extra time navigating the various sidetracks, but most seemed to be for forest access—not additional views of the ocean.

This region is notable for its beauty, but it also provides access to an interesting cultural opportunity as well. This is exactly what overland travel is all about, accessing remote areas and engaging with new experiences—something foreign to our day-to-day. It is also a reminder that adventures like this are often available in our own backyard. The Olympic Peninsula is filled with history spanning thousands of years; all there is to do is go and have a look.

Special Thanks:

This story was produced with the support of ARB USA, manufacturers of high-quality overland equipment for Jeeps, Toyotas, Fords, Land Rovers, and other brands.

The 2018 Jeep Wrangler JL Unlimited Featured in this story includes the new Overland Package.

“At ARB, we get Overlanding. We have been equipping offroaders since 1975 with the protection and capability necessary to enjoy the beauty of the Australian outback – and now, the rest of the world. Our world-renowned engineers have brought that same level of experience and expertise to the ARB Jeep Wrangler JL product line.

The Overlanding Package from ARB provides Jeep Wrangler JL owners with a one-stop-shop for all their Overlanding needs.”