As overlanders and remote explorers, we often find ourselves in unfamiliar territory, which tends to make us more aware of our surroundings. As a result, one of the most critical skill sets for us is observation. Looking is seeing with your eyes. Observing is seeing in detail, listening to sounds, watching interactions and movements, applying critical thinking to what you are witnessing, processing all of that input in a rational way, and forming a logical conclusion or hypothesis of the situation, resulting in a decision. That decision can range from continuing to observe or taking some form of action. There is also that inner voice, aka sixth sense or gut feeling, that should not be ignored because it’s likely your subconscious self is connecting all of the dots prior to your conscious self doing it. Noticing certain details and acting on them can determine the outcome of an event or mitigate an event from occurring at all.

If we become more aware and observant in unfamiliar territory, then the inverse of that must be true in that we become less observant in comfortable or familiar surroundings. When we are comfortable, we relax—not just physically but also mentally. How many times have you noticed something in your everyday environment that you never noticed before, yet was there all along? As Sir Arthur Conan Doyle states, “The world is full of obvious things which nobody by any chance ever observes.”

Last winter, we found ourselves in an interesting situation. Visiting our daughter, we decided to explore in the snow in a highly active OHV area. Having never been there before, I observed everything: the trail, the scenery, the people, the vehicles, their driving habits, etc. Turning to cross a wide, snow-covered meadow, I noticed a newer small SUV sitting 20 feet off the main trail. Dark gray against a white backdrop with no vegetation anywhere nearby, it was, in a word, obvious. I noticed the tires: they were street tires with snow built up around them and no tire tracks. There were also no footprints. Since we were following the others, we crossed the valley, stopping a short distance away. While the others had fun, I kept observing that SUV. No less than 20 vehicles drove past it on the main trail no more than 30 feet away, and not one stopped or slowed. Likely because it isn’t uncommon to see a vehicle parked on the side of the trail in an OHV area.

The last time it snowed was Thursday; it was now Sunday. I could see where a vehicle had circled that car in the snow but never approached it. A little voice kept telling me that something wasn’t right. Putting it all together, I decided to act: “We need to go look in that vehicle.” “Why?” the kids asked. I explained I thought there might be a dead person in the vehicle or someone in need of help. Dustin and Chase, being young men, instantly headed over to investigate the SUV, and soon they were shouting. I wish I had been wrong, but unfortunately, my suspicion was accurate. There was, in fact, a dead person inside the vehicle. So, the next few hours were spent with law enforcement.

Again quoting Doyle, “There is nothing more deceptive than an obvious fact.” Why quote him twice, you ask? Well, he invented Sherlock Holmes, the most observant character of all time. The point I’m trying to stress is this: that vehicle had been there for days, in complete view, right next to the trail, with a deceased person inside of it, and no one stopped. In just a short time, I had witnessed no less than 20 vehicles drive right past it. Over the course of days, that number would register 100 or more.

Observation becomes even more important in many of our efforts to blend in and disappear into the environment around us, be it natural or man-made. After all, the best way not to draw unwanted attention to yourself or find yourself in an otherwise avoidable situation is to appear as though you belong—to disappear into the surrounding environment. We strive to be, as Indiana Jones described Marcus Brody in Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, fluent in the language and culture, familiar with the terrain, completely able to fit in, blend in, and disappear. The reality for many people is they’d get lost in their own museum.

Observation doesn’t just happen; it takes discipline and effort: studying terrain and culture, learning languages, evaluating risks, keeping apprised of current events, and paying attention to the smallest details and happenings in the immediate vicinity. Then, processing all of those details into a comprehensive evaluation and understanding of the situation or environment one finds oneself in. For us to be travelers and genuinely have more meaningful experiences with other cultures, we must skillfully observe in order to have any chance of understanding or blending in.

To achieve that level of comfort, we must not only skillfully observe the finite details but also take advantage of the converse of what I outlined above—people in familiar environments tend to not pay as much attention to small details as they would in unfamiliar territory. Given their familiarity, most people are not as vigilant or aware. They tend to overlook small details such as the slightly odd shape in the brush a few hundred yards off the main track, which in reality is your exploration rig with the rooftop tent deployed and you inside.

Fortunately, observation is a skill set that can be developed. There are many activities you can do to augment your explorations and travels in addition to your everyday life. I have found nature journaling, field notes, sketching, and water-coloring all to be beneficial. Each requires you to have patience, concentrate on both the big picture and fine details simultaneously, reflect upon what you observed, and then relate it on paper.

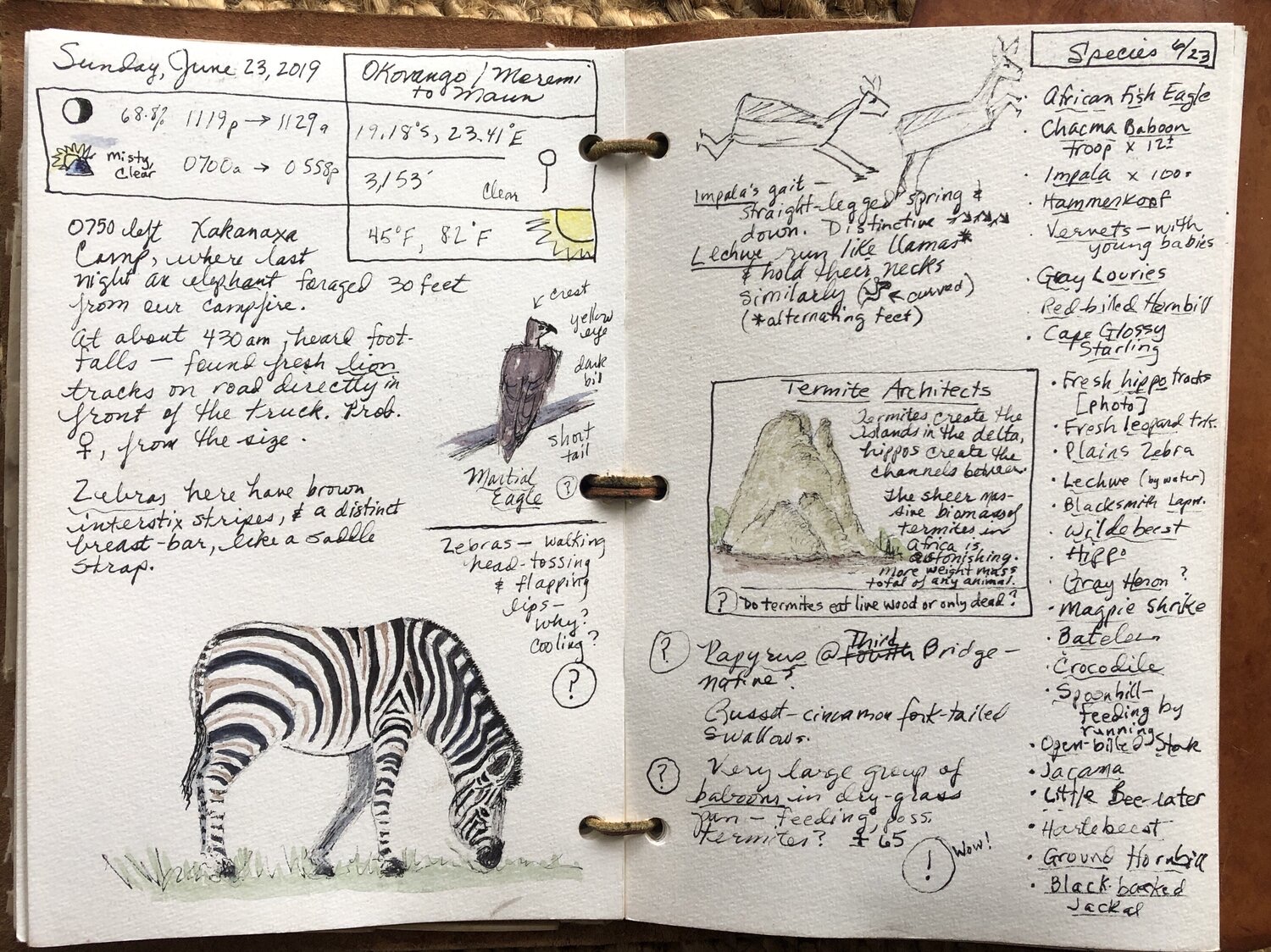

Roseann Hanson, Founder of Exploring Overland’s Field Arts Institute, puts an extremely high value on field journaling and sketching as a way to force paying attention to details. In her field journals, Hanson captures not only the visual details but also weather, temperature, humidity, sun/moon positions, date and time, and zeroes in on the important details while keeping its context in the bigger picture. She also takes it a step further by adding watercolor images to her field journals which have the added benefit of capturing color, contrast, and dimension. Per Hanson, “Field or nature journaling is an excellent way to develop observation skills because it forces one to stop and take in the surroundings and then start identifying the details. Then writing them down or drawing them further reinforces what was observed.”

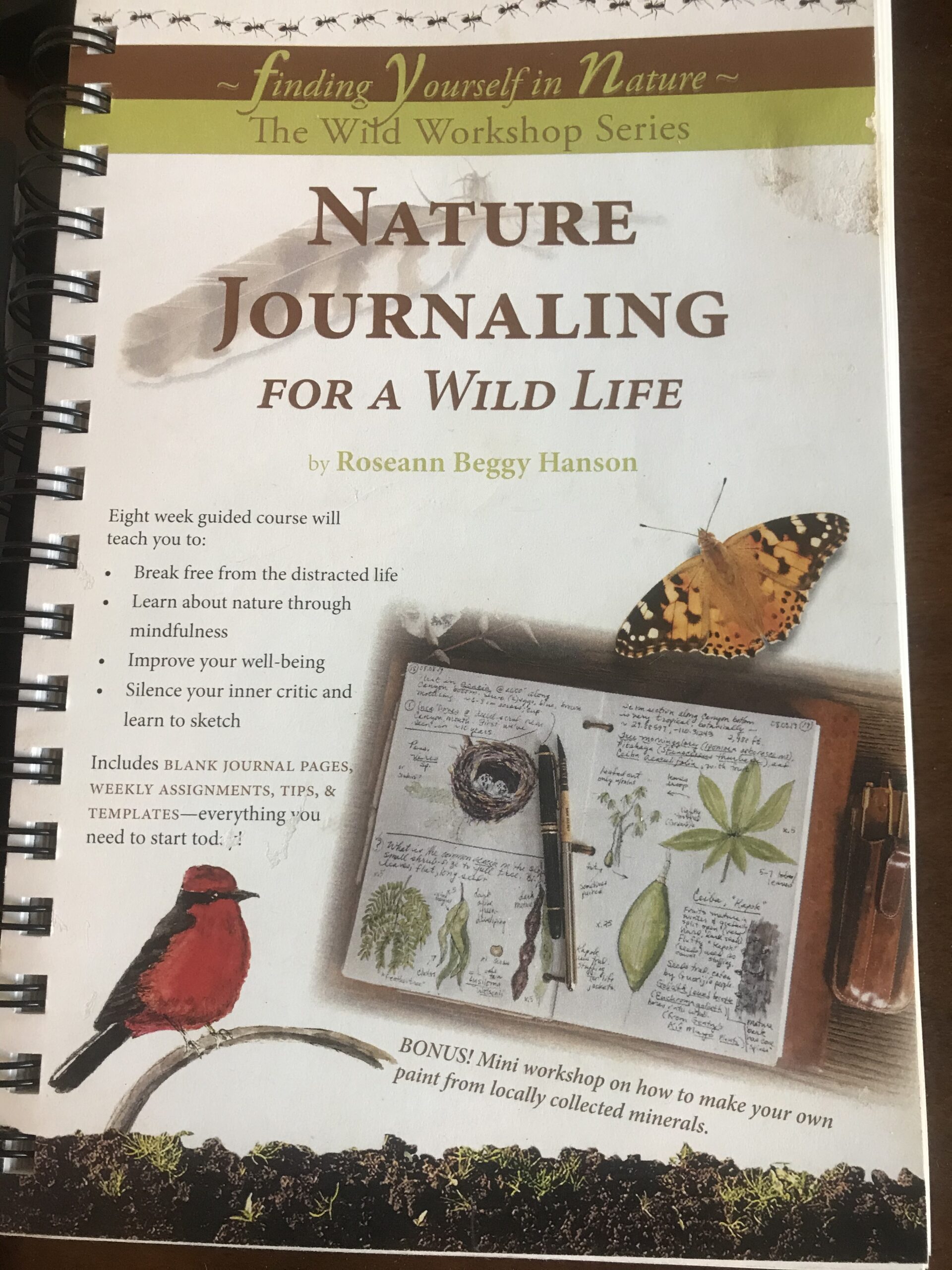

Hanson has published an extremely useful book titled Nature Journaling for a Wild Life that does an excellent job of walking an absolute beginner through the steps and skills to successful nature journaling, field notes, and sketching by providing a self-guided eight-week course to develop skill sets that build upon one another. Her book concisely states the key benefit and purpose of nature journaling as “the art of seeing instead of looking.” Moreover, she also offers many online tutorials and teaching sessions which are immensely useful in building this skill set. You can find her, her materials, and tutorials at exploringoverland.com/fieldarts.

Back to my experience, I don’t for one second believe people intentionally avoided checking that vehicle. But most people who frequent an OHV area are typically more relaxed than they would be in a truly remote or foreign environment. OHV areas generally are well-frequented, close to infrastructure, and short duration. That vehicle, upon a first glance, looked just like any other vehicle parked alongside the trail. It was only with a more refined observation of the details that the facts formed a very different possibility. Upon reflection, it was, as Doyle pointed out, a very obvious fact that went unnoticed.

Observation is a proficiency of multiple skills that collaborate to expose the finer details missed by merely looking. For the explorer of any level or discipline, observation should be considered an essential skill to develop and possess, right alongside repairing a tire, properly using a winch, and Tread(ing) Lightly. It will not only help people avoid potentially negative circumstances but help them become wholly immersed in the environment they are exploring in the first place.