Photography by Frank and Helen Schreider

Frank and Helen Schreider were preparing to leave for the island of Flores, Indonesia, when the village chief in Komodo brought bad news. “There is no road at Labuhan Badjo,” he said, running a calloused thumb eastward over their map. “It starts here, at Reo.” Their map of Flores clearly showed a road, but the chief was adamant. “There is no road.”

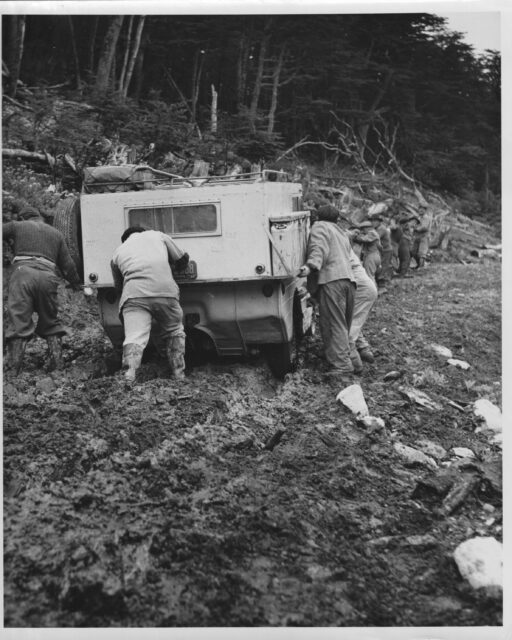

Trusting the local intel, the Schreiders recharted their course. The extra detour by land and sea would drain their fuel and water tanks long before they reached Bajdo. With no chance to send for more gasoline to fuel their amphibious Jeep, Helen and Frank studied tide charts and US Navy nautical books, hoping for an obvious solution. But as the sky darkened, heavy waves crashed while the air’s sweet smell predicted rain. Monsoon season was quickly approaching, reminding the Schreiders that half a thousand miles of unpredictable conditions remained, potentially threatening their trans-Indonesian expedition.

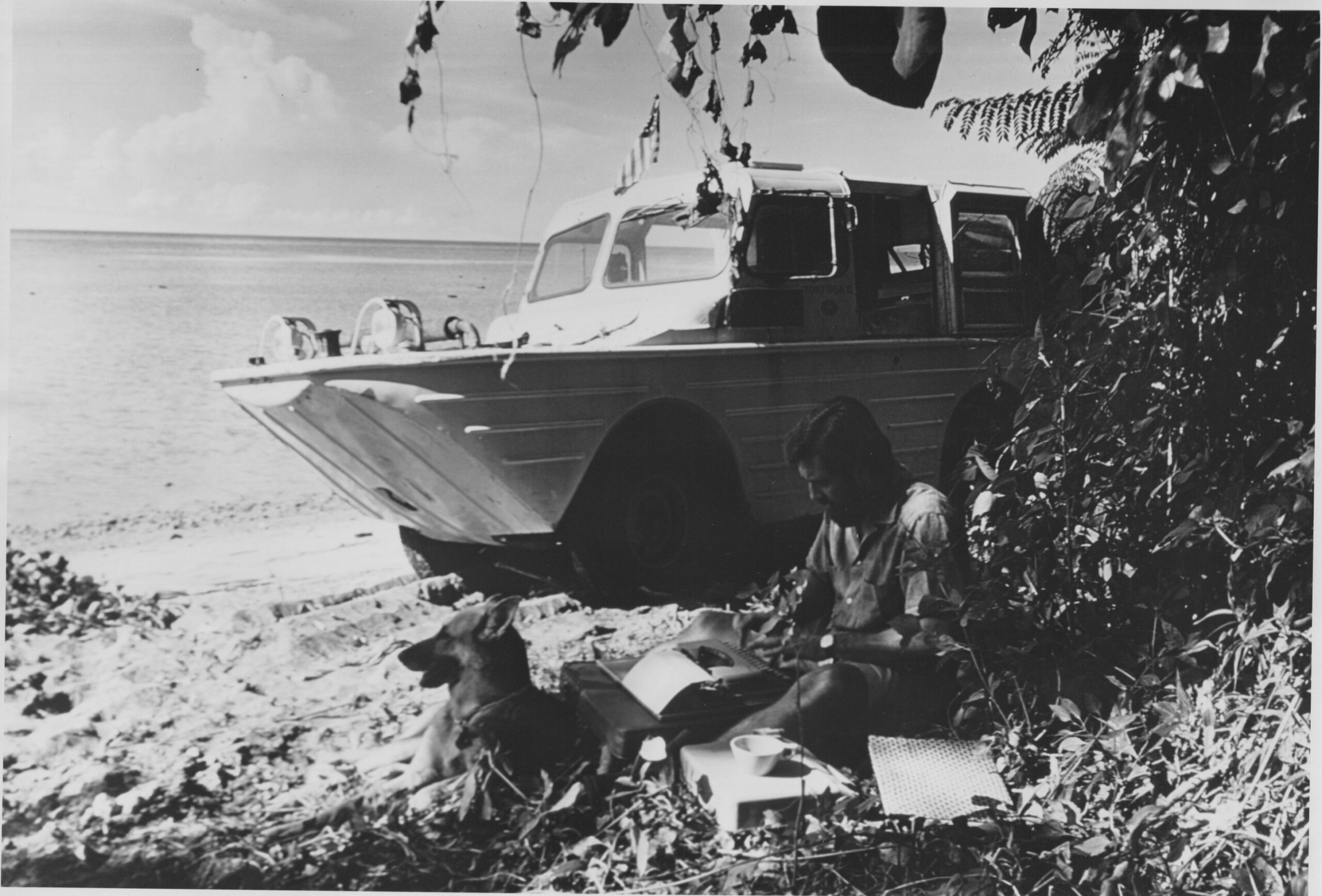

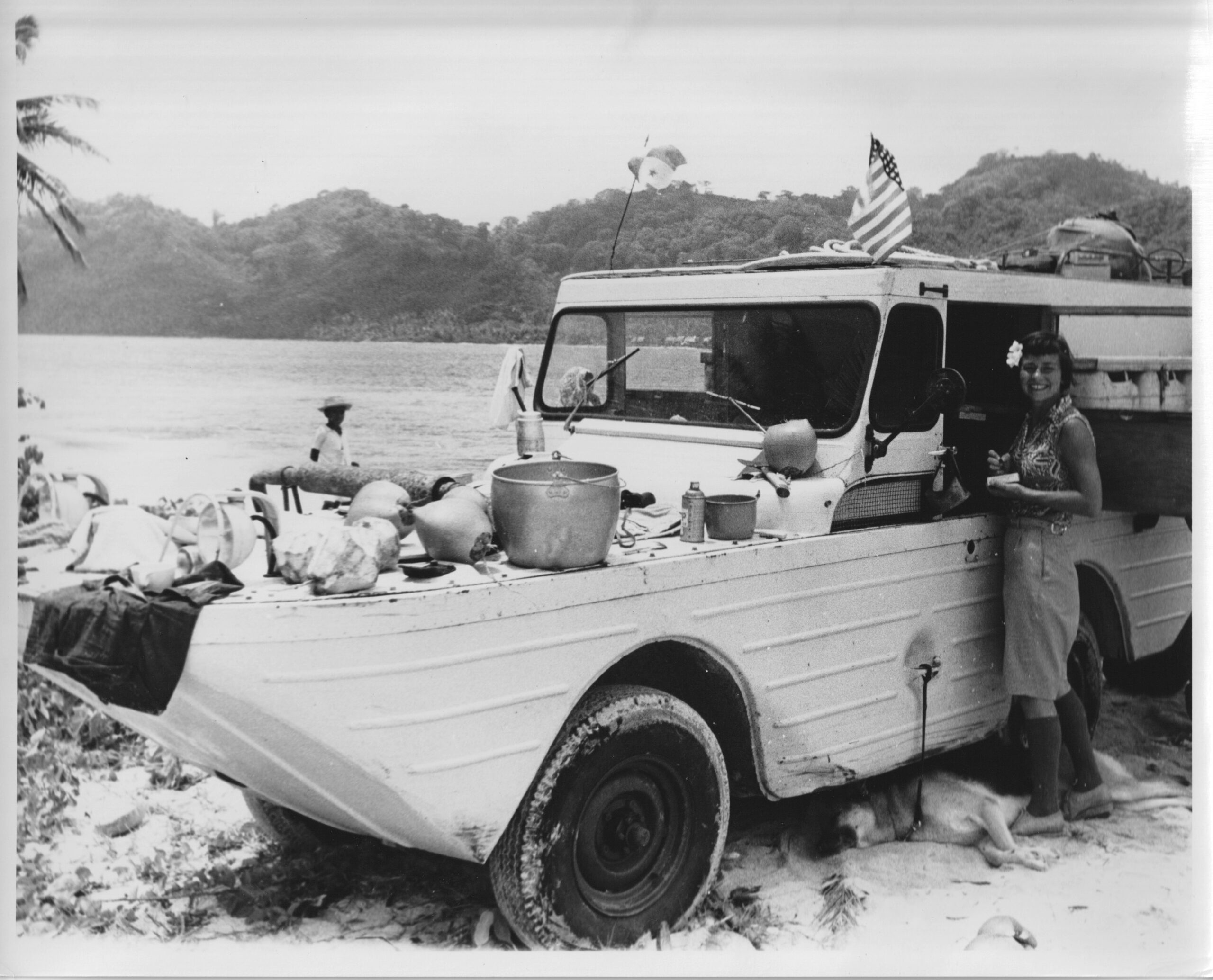

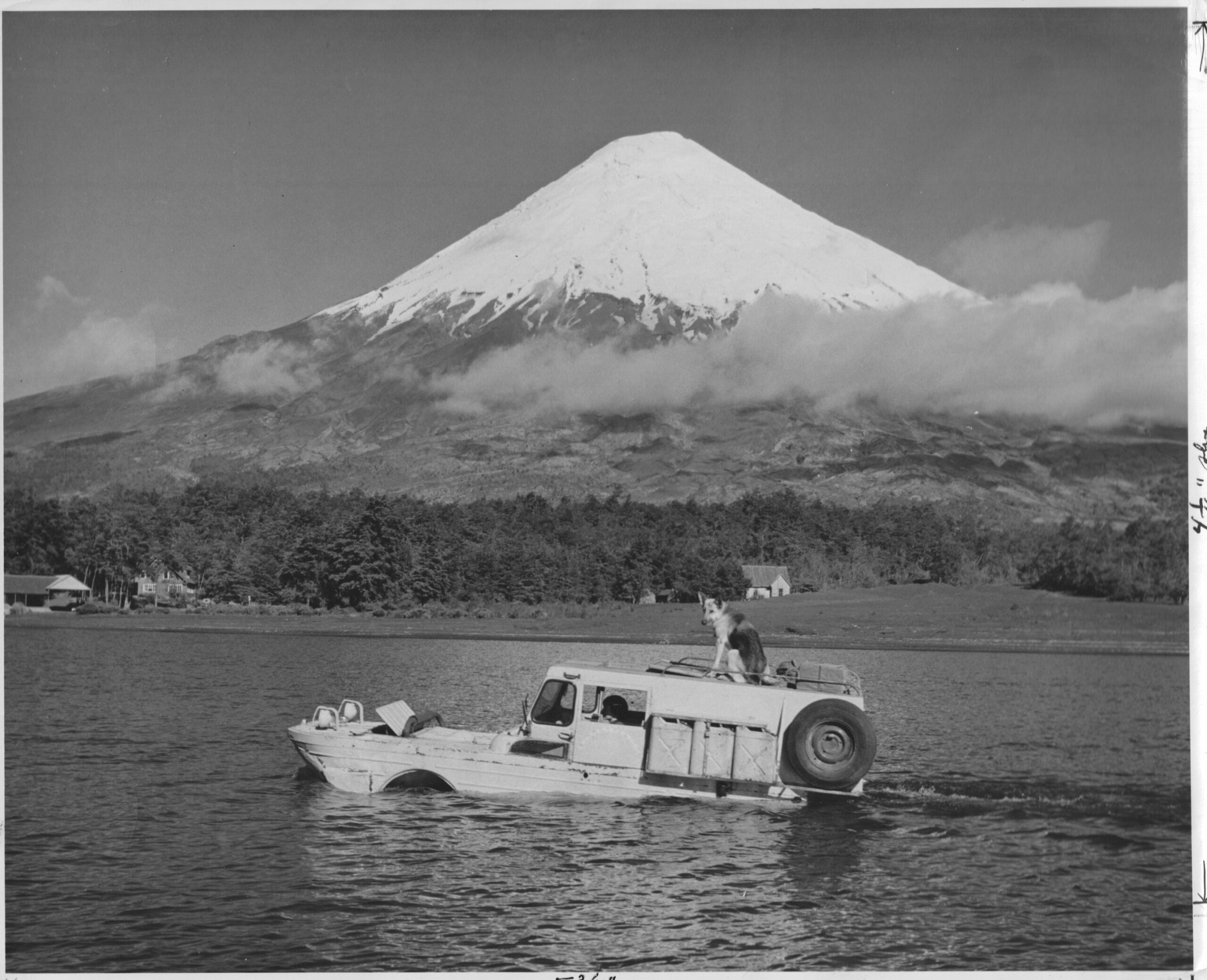

In 1961, American explorers Helen and Frank Schreider, and their trusty German shepherd, Dinah, embarked on a 5,000-mile National Geographic assignment along the Indonesian chain of islands from Sumatra to East Timor. Their vessel, Tortuga II (the Spanish word for “turtle”), was a WWII-surplus-seafaring Jeep modified to travel by road and by water—an intentional choice to traverse an archipelago of over 18,000 islands stretching nearly to the Australian coast and bordered by the Indian and Pacific oceans.

The 30-something adventurers met at the University of California in Los Angeles, where Frank studied engineering and Helen majored in fine arts. They tied the knot in 1947 and spent their honeymoon bushwhacking for eight days through 200 miles of Mexican jungle in a different Jeep, unsuccessfully penetrating the roadless track in southern Costa Rica.

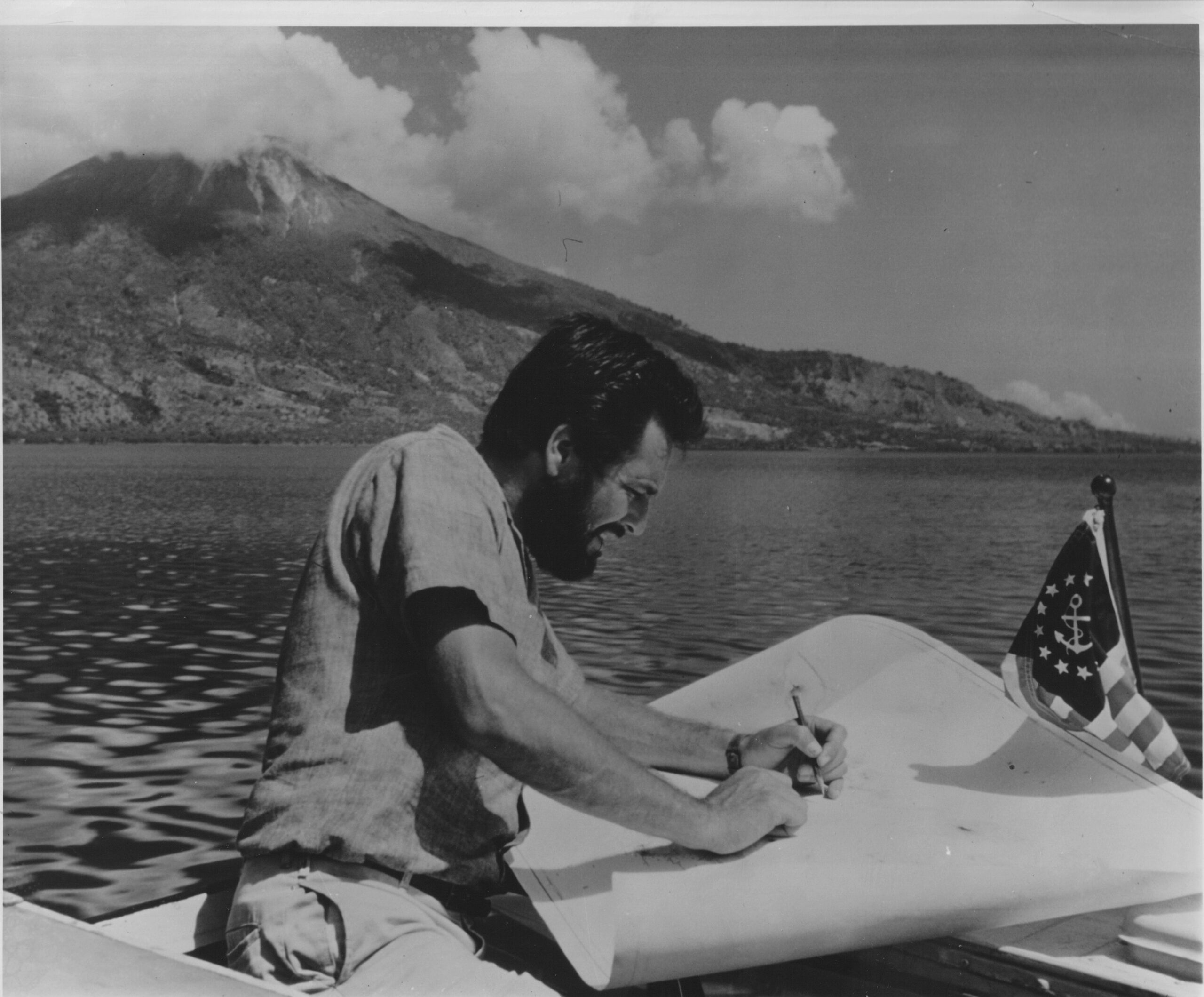

Frank served in the US Navy’s submarine service in the Pacific during World War II. According to Helen, he was an enthusiastic reader during childhood, which resulted in a passionate desire for travel. With a shock of thick brown hair, a knack for mechanical problem-solving, and the ability to winch the bulky Tortuga II out of just about any predicament, Frank was also the man behind the typewriter, undertaking much of the writing.

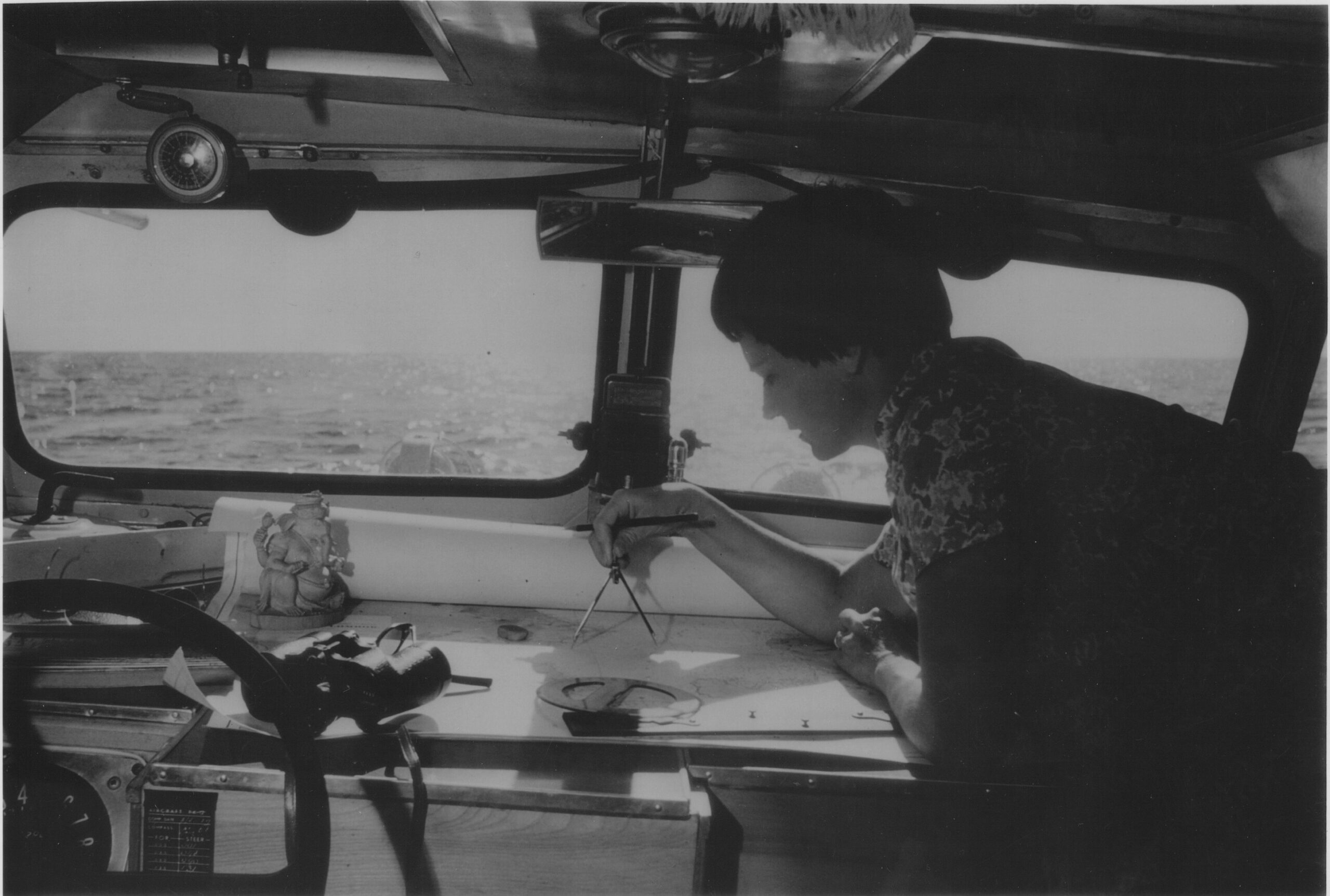

An avid drawer and painter, Helen took most of the photographs during the couple’s expeditions. Whether she was piloting Tortuga II up the Ganges River in India or wild camping on Indonesian beaches, her crisp sundresses and well-tailored outfits displayed an elegance and put-togetherness of the time. Don’t let her wide smile and knack for pulling off a short pixie cut fool you, though. While she didn’t enjoy crossing shallow reefs or pushing the limits of the Jeep’s camber off-pavement, Frank marveled at his wife’s ability to remain calm, quietly murmuring encouragement during raging sea storms off the coast of Panama or in response to concerning sounds emanating from Tortuga II’s engine while grinding up a steep shingle beach at Timor. Her response to Frank’s seemingly wild and crazy ideas was often, “When do we leave?”

The inception of the Indonesian expedition arose five years earlier, on a journey from Alaska to Argentina. At a busy Peruvian café in Callao, with views of ocean swells and soaring gulls, an elderly Dutchman invited them to join his table. “I would have given anything to have had a vehicle like yours when I was in the Indies,” he said, referring to the first amphibious Jeep they used to bridge roadless sections of the Pan-American Highway.

Over cold pisco sours, the former tea planter told the Schreiders of Komodo’s dragon lizards and Lubu tribesmen who lived in trees and hunted with blowpipes. “On the green cool nights, with the rice fields silver in the moonlight, he used to sit under a banyan tree on Java and listen to the music of the gamelan or watch a shadow play,” reads Frank and Helen’s travelogue, The Drums of Tonkin. The Dutchman continued, “That was paradise on earth.”

However, when the Schreiders landed in traffic-filled Jakarta, they were greeted by a troubled country in a state of emergency where journalists were under special surveillance. “This then —ruinous inflation, banditry, civil war, martial law—was the state of affairs when we arrived in Indonesia,” Frank wrote. But they weren’t in the country to report on President Sukarno’s nationalist agenda or bandit terrorism. The couple was searching for something else: “the Indonesia of laughter and music, of dancing, painting and sculpture, the Indonesia whose cultural heritage, both indigenous and imported, at one time made it the greatest country in Southeast Asia.”

To access this “paradise on earth,” the Schreiders needed to jump through several hoops. First, they required a vehicle fit for the journey. The couple sourced a Ford GPA “Seep”—the amphibious version of the WWII Ford GPW Jeep—from a surplus depot in California. Because the Seep’s WWII production was quickly terminated due to poor field performance (“It had the unpopular habit of sinking with no more provocation than a ripple,” Frank noted), the couple’s work was cut out to transform the blundering beast into a liveaboard boat truck.

A propeller at the rear and a rudder connected to the steering wheel by steel cable made the vehicle seaworthy, while drive shafts running to all four wheels allowed the Schreiders to eventually leave Jakarta, breathing in the scent of frangipani and chilis cooking in coconut oil as they passed nearby fishing villages. The 15-foot Tortuga II was equipped with a dual-cooling system for sea travel, a calibrated compass, and a chart table for navigation. The enclosed galley featured an alcohol stove and tiny sink with water piped from a 10-gallon tank in the bow. Cabinets held enough tinned food for two months off-grid, and fuel tanks carried enough gasoline for 150 miles at sea or 270 miles on land. The Standard Vacuum Oil Company arranged for 300 additional gallons of gasoline and motor oil to be delivered by prahu, a traditional Indonesian sailboat, to the main islands along their route.

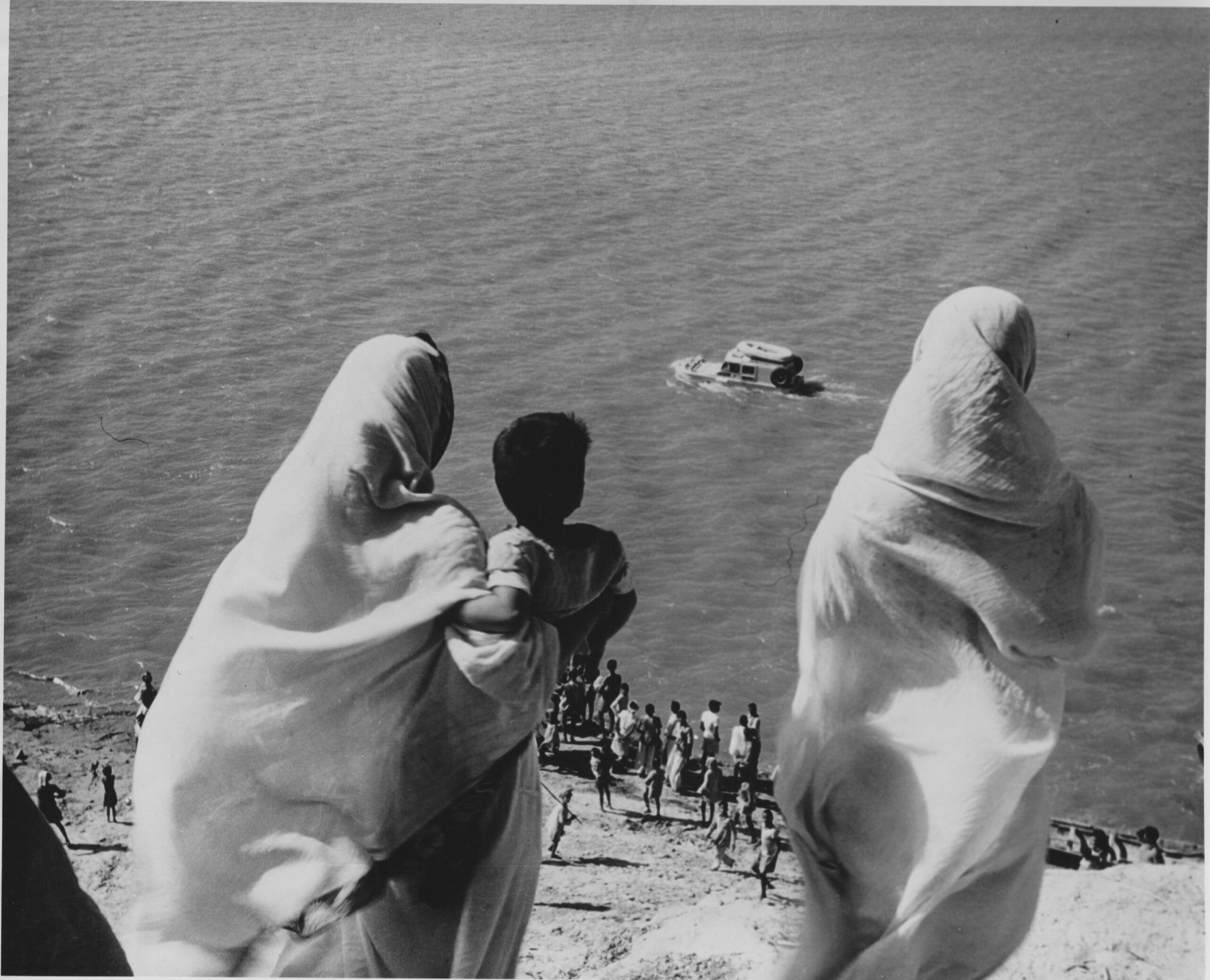

Painted white with cherry red wheels, Tortgua II turned heads wherever it went. In Jakarta, the seafaring Jeep evoked a big grin and thumbs-up from local traffic police, who exclaimed, “Bagus, tuan!” or “Okay, sir!” in response. Outside the capital, the strange “land ship” attracted children by what Frank described as “that unexplainable aura that exudes from anything or anyone strange to the countryside,” drawing the elders to investigate and invite Frank and Helen, once they confirmed their nationality was American and not Dutch, to their village to observe a ceremony or share a cup of tea.

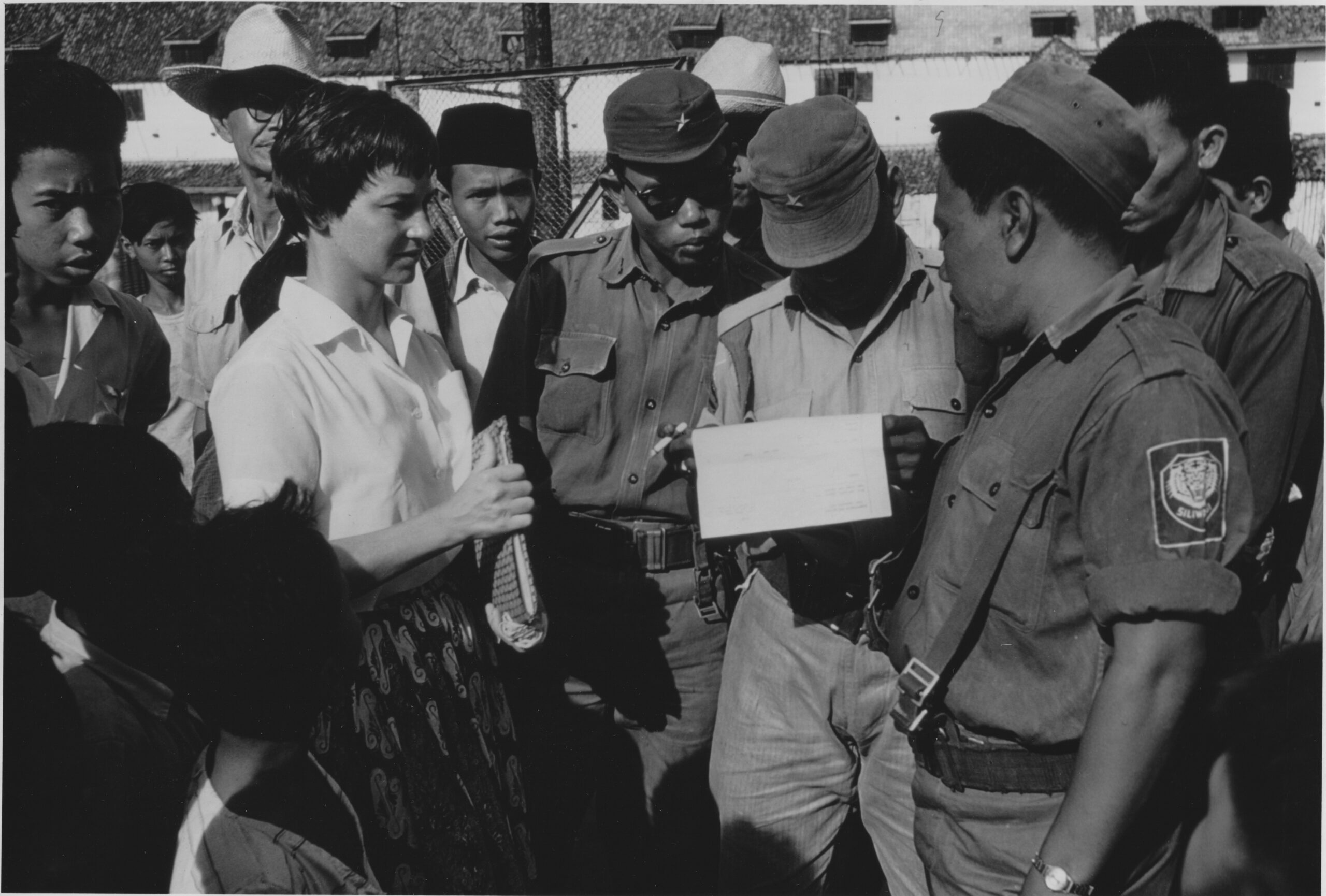

The next logistical challenge was a bureaucratic one. The Schreiders were required to register with the local police across the country, securing permits to take photographs, eventually leaving Jakarta with a letter from the colonel of military intelligence requesting all authorities assist them on their journey. One morning, after they made a wrong turn while driving to the prerequisite government offices to secure additional permits, a sentry man shot at their vehicle with a .30-caliber gun. Arriving at the military commandant’s office, the officer smiled apologetically. “But you know, Indonesia is in a state of war and emergency.”

A basic understanding of Indonesia’s complicated political and economic climate during the Schreiders’ visit in the early 1960s requires a brief history lesson on the country’s path to independence and the events that spiraled from it. Indonesia proclaimed independence on August 17, 1945, marking an end to Japan’s World War II occupation and 350 years of Dutch colonial rule—at least temporarily. Only after another four years of guerrilla warfare, in which Dutch forces burned villages and carried out mass detentions, torture, and executions, were the Indonesians granted independence (minus West Papua, but that’s another story).

Indonesian scholar and historian Dr. Taufik Abdullah identifies a multi-faceted Indonesian identity in the 1950s—a country that had achieved independence and was working toward democracy, press freedom, and a new constitution; and an Indonesia plagued by political instability, institutional weakness, and a struggle for power. The Indonesian people had experienced a war and a revolution. “It was also a post-colonial state, which implied it was primarily designed to control and extract, not to support a nation and guarantee citizenship,” Abdullah wrote in Indonesia: Towards Democracy in 2009.

By the early 1960s, a power struggle was well underway between President Sukarno, the army, the Communist Party, and rebel groups. Sukarno called for strict government control, curtailing freedom of the press, radio, speech, assembly, and movement. That was a problem for two journalists looking to journey to the far-flung reaches of the country.

A few miles out of Jakarta, Frank and Helen sighed deeply, relishing the scents of freshly churned earth and drying coconut flesh. “Away from the suffocation of Jakarta’s delicately balanced protocol and red tape, its tensions and superficial gaiety, its restrictions and registrations, we felt a new lightness and freedom,” Frank wrote. In Bali, amid Galungan festival celebrations, the pair attended a cremation ceremony. Flames licked at the wooden cremation tower, which was decorated with gold and silver streamers and glass chips. Shouts rang out to frighten evil spirits while an orchestra of “bamboo rattles, flutes and xylophones played a happy melody.” On Lombok, the Schreiders were invited to attend a circumcision ceremony from a neighboring village chief and joined a celebratory feast complete with buffalo meat curry and “mounds of rice, eggs fried in coconut oil, tiny silver fish eaten whole” and cone-shaped sugared rice and coconut.

Eventually, the duo arrived in Komodo to observe the renowned 5-foot dragon lizards named after the island. But with half a thousand miles to go to Timor and an approaching monsoon season, they didn’t have time to linger as they liked and quickly prepared to leave for Flores, the next largest island to the east. Komodo was where the local chief informed the Schreiders that the road they so desperately needed no longer existed.

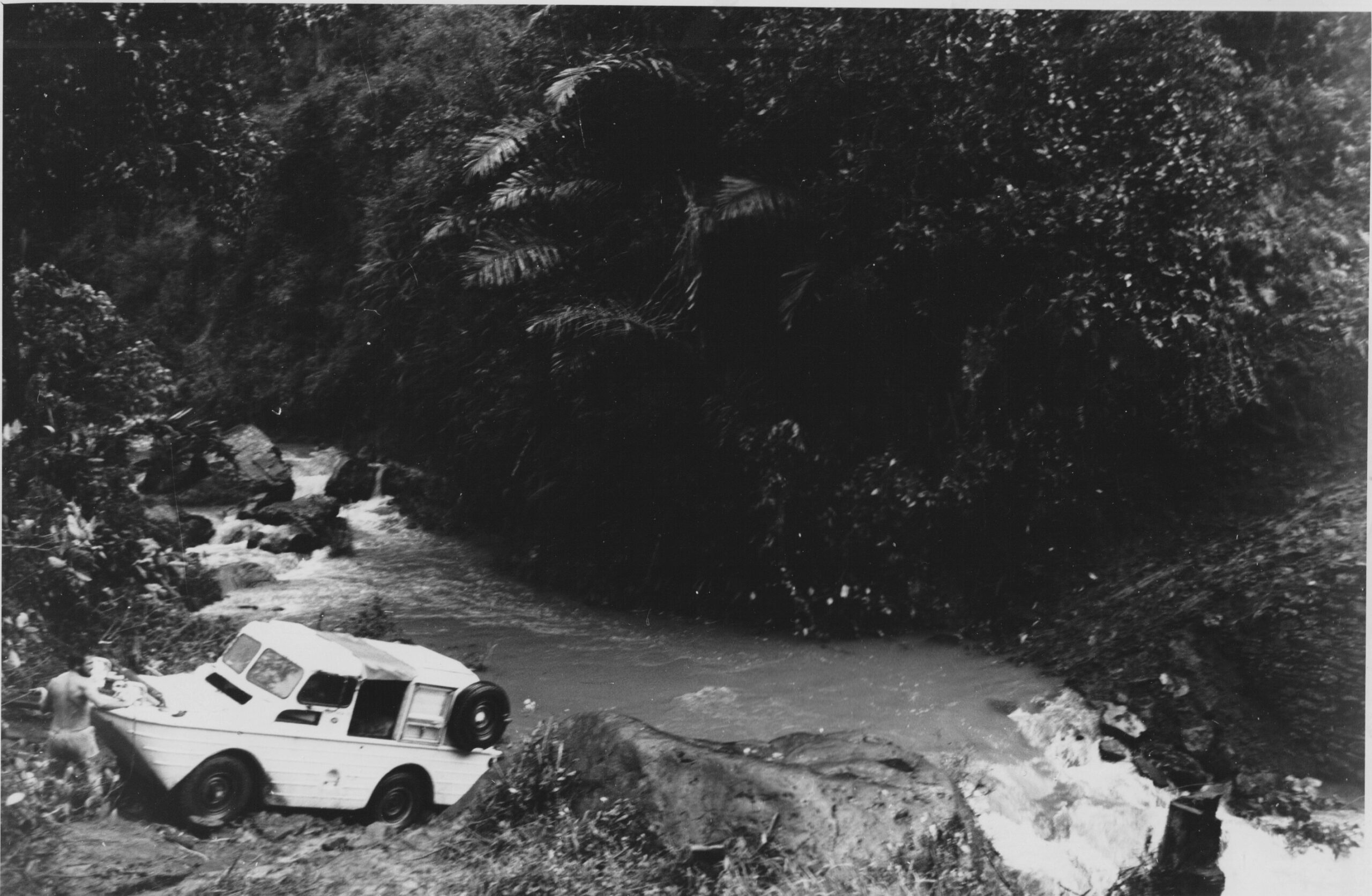

Despite the risk of draining their fuel and water tanks well before reaching land, Frank and Helen took off from Komodo in the early morning. Opting to use the ebbing current to push the Jeep toward Flores, the route was the shortest but far from the safest. However, there was a slim chance that if they used the current to their advantage, they might reach Flores before their tanks ran dry. “Rocks and islands sped by at what seemed full-throttle speed with but a whisper from Tortuga’s exhaust,” Frank wrote. “And the sea life, heretofore shy of an engine’s foreign sound, was bolder.” Leaping marlin and graceful whale sharks, leaving a trail of bubbles, kept them company while 6-foot-long sea snakes swished through the translucent water beside the Jeep.

As Helen and Frank continued along the coast, their charts, which were the most up-to-date available, became more inaccurate. No extensive survey had been completed of the area since before World War II. Unexpected reefs appeared, and landmarks to plot vanished. Using a bamboo pole to check the depth before crossing shallow waters above glowing mauve reefs, they spotted blue starfish and spiny black sea urchins. “By the fifth day out of Komodo, our spare fuel tanks were dry, our main tank was considerably less than full, and our drinking water was almost gone,” Frank wrote. The gas gauge developed an “erratic flutter” while the waves rocked Tortuga at precipitous angles.

By the time they were 15 miles from Reo, the gas gauge had stopped fluttering, hanging instead at the empty mark. “We looked for a place to land, but dark scrub jungle and mangrove roots reached like fingers into the sea,” Frank wrote. “There was no place to beach Tortuga.” The Schreiders crept closer to shore for another hour, the fuel pump sucking air while the engine sputtered. Finally, with only four miles of fuel remaining, they landed on a smooth beach on the outskirts of Reo. A surprised crowd gathered on the beach; one of the men brought a coconut for Helen.

But within minutes of their arrival, a truck sped down the road from the main part of town. Frank noticed a “strange hush fell over the crowd” as the truck “careened over a small bridge and skidded to a stop near an old concrete pillbox.” Restraining a growling Dinah, the Schreiders eyed the Indonesian Army lieutenant joined by a platoon of helmeted soldiers as they inundated the crowd. Strapped with submachine guns and automatic rifles fitted with bayonets, the crew sported “the mottled jungle-combat camouflage uniform of olive-drab and green.”

How ironic, thought Frank, to sweat out the long voyage from Komodo only to become the major characters in an “incident” on Flores. The sergeant, approaching the couple, reached to grab something from a wooden case in the back of the truck. “Welcome to Flores,” he said, and with a wide grin, handed them a bottle of warm beer.

***

As Frank and Helen’s 5,000-mile, 13-month Indonesian expedition drew to a close, they knew they had experienced much of what the old Dutchman idealized about the country. But, as Frank wrote, “We had found so much more.”

Shortly after, the Schreiders were hired full-time by National Geographic. Their next assignments involved exploring Africa’s Great Rift Valley by Land Rover, following in the footsteps of Alexander the Great from Greece to India (also by Land Rover), and, finally, mapping and navigating the length of the Amazon River.

The couple continued with National Geographic until 1970. Frank went on to write as a freelancer and continued his seabound capers aboard his boat, Sassafras. He died suddenly of a heart attack while moored in Crete on January 21, 1994.

Helen joined the National Park Service as a museum designer and continues to paint to this day. At age 89, she was inducted as a National Fellow into the Explorers Club in 2015. Frank was made a member in 1956, but the club didn’t allow women until 1981.

The Schreiders published several books, including 20,000 Miles South: A Pan American Adventure (1957), The Drums of Tonkin: An Adventure in Indonesia (1963), and Exploring the Amazon (1963).

Editor’s Note: Indonesia by Amphibious Jeep was originally published in Overland Journal’s Fall 2023 Issue.

Our No Compromise Clause: We do not accept advertorial content or allow advertising to influence our coverage, and our contributors are guaranteed editorial independence. Overland International may earn a small commission from affiliate links included in this article. We appreciate your support.