Coen turned into a driveway and parked underneath a huge mango tree, its shade transforming the patio into a pleasant retreat from the blazing sun. An elderly man walked up to the Land Cruiser and in Low German Coen explained who we were and why we were there. Yes, our directions had been correct: the man was Frans, the mayor of the settlement we had been looking for.

Little House on the Prairie in Paraguay

I got out of the Land Cruiser, ready to meet Frans’ wife and children who stood on the veranda. However, the moment my feet touched the ground the children shrank back, the little ones hiding behind their mother’s skirt. Was I wearing some kind of scary mask? It took me a second to figure out that this was probably the first time in their lives they saw a woman wearing pants instead of a skirt, with loose hair and no headscarf. Maybe I did look as if I came from another planet.

We think traveling may be scary at times, but have you, as a traveler, ever considered what it is like for people who rarely leave their homes to suddenly see a totally different-looking person whom they can’t place anywhere within their frame of reference? How utterly frightening that may be to them?

It had not been easy to find this place. The settlement wasn’t the typical South American town characterized by a plaza surrounded by houses, but consisted of a collection of farms running along straight, unpaved roads lacking road signs. On our way here we had stopped at an intersection and since Coen speaks Low German, he had been the one to step out of the Land Cruiser to ask for directions from two women dressed in purple dresses and bonnets – they would fit in any Little House on the Prairie scene – who were approaching the crossing in their buggy. Their eyes grew large at the sight of Coen walking up to them, which was when we realized how far away these people are removed from our society where men and women usually interact in an easy-going manner, even when they don’t know each other.

The Mennonite Community of Friesland

We were also aware that without an introduction we would not have been welcome here. That introduction had come from Johan and Helena, whom we had met the week before in the moderate Mennonite colony of Friesland. On our arrival, one late Saturday afternoon, the town had appeared deserted. We stood amidst dead-quiet, empty streets and wondered where everybody had gone. Coen looked at the church and, more importantly, at an inviting stretch of green around it. Could we camp here?

A man was just coming out of a house. We introduced ourselves and met Helmut, the minister. While he couldn’t allow us to camp here, he referred us to the nearby Tannenhof Hotel – “Surely you can camp there” – and invited us to join the Sunday morning service, the following morning.

The town, home to some 700 inhabitants, was reminiscent of The Stepford Wives, (film based on the homonymous book The Stepford Wives by Ira Levin) with an incredibly organized set-up, with neat houses and clean streets, and tidy gardens with meticulously trimmed hedges. It oozed tranquility and such a level of organization and efficiency that it could easily pass for a German village. It definitely was a far cry from anything we had seen in Paraguay, where rural towns had unpaved streets and were characterized by disorder (by no means unpleasant).

Mennonite History in a Nutshell

While the founder of the Mennonites originated from the Netherlands (Menno Simons, 1496-1561), most of his initial followers came from Germany. Mennonites have lived through many phases of persecution, being sent to Russia, back to Germany and, after WW II, crossing the ocean to countries like Canada, Mexico and Paraguay.

Why Paraguay? Well, at the end of the 19th century Paraguay’s megalomaniac leader Lopéz waged war against Brazil, Uruguay and Argentina (the Triple Alliance War). Paraguay lost twenty-six percent of its territory and more than half of its inhabitants. Clearly Lopéz could use some people to rebuild the country! As a result he offered Mennonites to colonize the western part of Paraguay, an area called the Chaco. Here, the Mennonites have continued speaking their own language, Low and High German. In some of their schools children are taught Spanish and Guaraní – the latter is the indigenous people’s language, and is Paraguay’s second national language – but don’t speak these languages at home.

The Mennonites were allotted wilderness, lands nearly impossible to cultivate, impenetrable forests and swamps. Now, two to four generations down the line, they are mostly rich colonials even though they arrived with nothing, most of them having lost everything during their migrations. What they have now is the result of years of working their fingers to the bone – six days a week from sunrise to sunset, without any support from the government. They have kept up their own traditions and customs, weren’t interested in integrating at any level and have mostly stuck to themselves (only in the last fifteen years or so have some started to marry Paraguayans).

In the 1990s relations between the Paraguayans and the Mennonites deteriorated. With the Mennonites accumulating wealth, the Paraguayans became envious and started stealing and killing cattle of the Mennonites. The Mennonites searched for a peaceful solution in the form of neighbor support (nachbarshaft-hilfe): advising Paraguayans on how to work their lands as well as providing education, which has had very mixed results.

Later on our journey we heard another side of this story, from Germans who had lived among the Paraguayans for eight years. They argued that the Mennonites’ nachbarshaft-hilfe is not so much about doing good but wanting to convert the Paraguayans. Apparently the reason for this is that the law states that Mennonites are not allowed to buy land from indigenous people but can buy land from other Christians. Which only goes to show how many stories have two sides, and how hard it is to – as a traveler, an outsider – to get a complete picture of lives in foreign countries. Maybe that is never truly possible, no matter how hard we try, as there are often more truths to one story.

Meeting Friesland’s Congregation

Early next morning, at the sound of the first cars passing the hotel grounds, we followed the crowd to the church. We are not churchgoers and wouldn’t have gone without an invitation, but we were curious to learn more about this community and church seemed a logic place to start. Helmut received us in a cordial manner and introduced us to the congregation. The service was in High German and similar to a (moderate) Protestant service in the Netherlands.

After the service we met Helena and Johan, a super friendly, outgoing couple who invited us to stay at their home for a couple of days. Of course we said yes. Johan was born in Mexico, the country his parents decided to leave when cars were introduced, which didn’t fit in with their conservative lifestyle. The family moved to Paraguay, which still had (and has) a number of conservative Mennonite colonies (similar to the Amish in the US). Johan grew up in a settlement without modern conveniences such as cars and television. When he and Helena married they moved to the capital of Asunción, where a new world opened up to them. “We literally experienced a rebirth,” Johan explained. “As a result we became too liberal in our way of thinking and way of life. Returning to our hometown was no longer possible and instead we came to live here, in the colony of Friesland.”

Frans’ and Lisa’s home

When we said our goodbyes, Johan emphasized not to skip his hometown. “It will give you a good idea of how different our colonies are,” he said. Dark red, unpaved roads meandered through a green landscape and via another colony called Volendam we found our way here. Frans introduced us to Lisa, his wife, and together we drank a tereré, Paraguay’s cold version of Argentina’s and Uruguay’s ubiquitous mate (a herbal tea).

Lisa told her story about how she had arrived here, also coming from Mexico. When she was eleven, her mother died and her father remarried the same year. The woman already had nine children, her father eight. Together they had another one, so there would be twenty of them around the table. They left Mexico in 1969 when Lisa was fourteen, and moved to Paraguay. Here everything was jungle and had to be bulldozed – by hand. They ate what the forest gave: wild boars, armadillos and rats. It took several years to learn what would grow in this soil. Oats and beans for example, which had grown well in Mexico, didn’t do well here. In the end they discovered soya and this is what they have been growing ever since. Meanwhile cars found their way into this conservative colony, although it was still tradition to go to church in the family buggy, the horse-drawn carriage.

Lisa offered us to use their shower and Frans invited us to dinner. “To eat something else for a change,” he suggested. One of the daughters was cooking vegetable soup and hamburgers. “Ah, real hamburgers,” I said and she gave me a bewildered look, so I swallowed the words, “A nice change from those gooey McDonald things.” It wouldn’t have made any sense to her.

Feeling welcome

The next morning we asked if we could see their church, and Frans gave us directions. Women were working in their vegetable gardens, protecting themselves from the sun with bonnets with colorful ribbons. When a farmer approached on his tractor, Coen explained why we were here. He turned out to be the former key-keeper of the church and introduced us to Anna, who now had that responsibility. “Would you like to go in the buggy?” she asked. The horse was harnessed to the carriage, and she and her husband Johan took us to the church. With the heavy springs it was a comfortable ride.

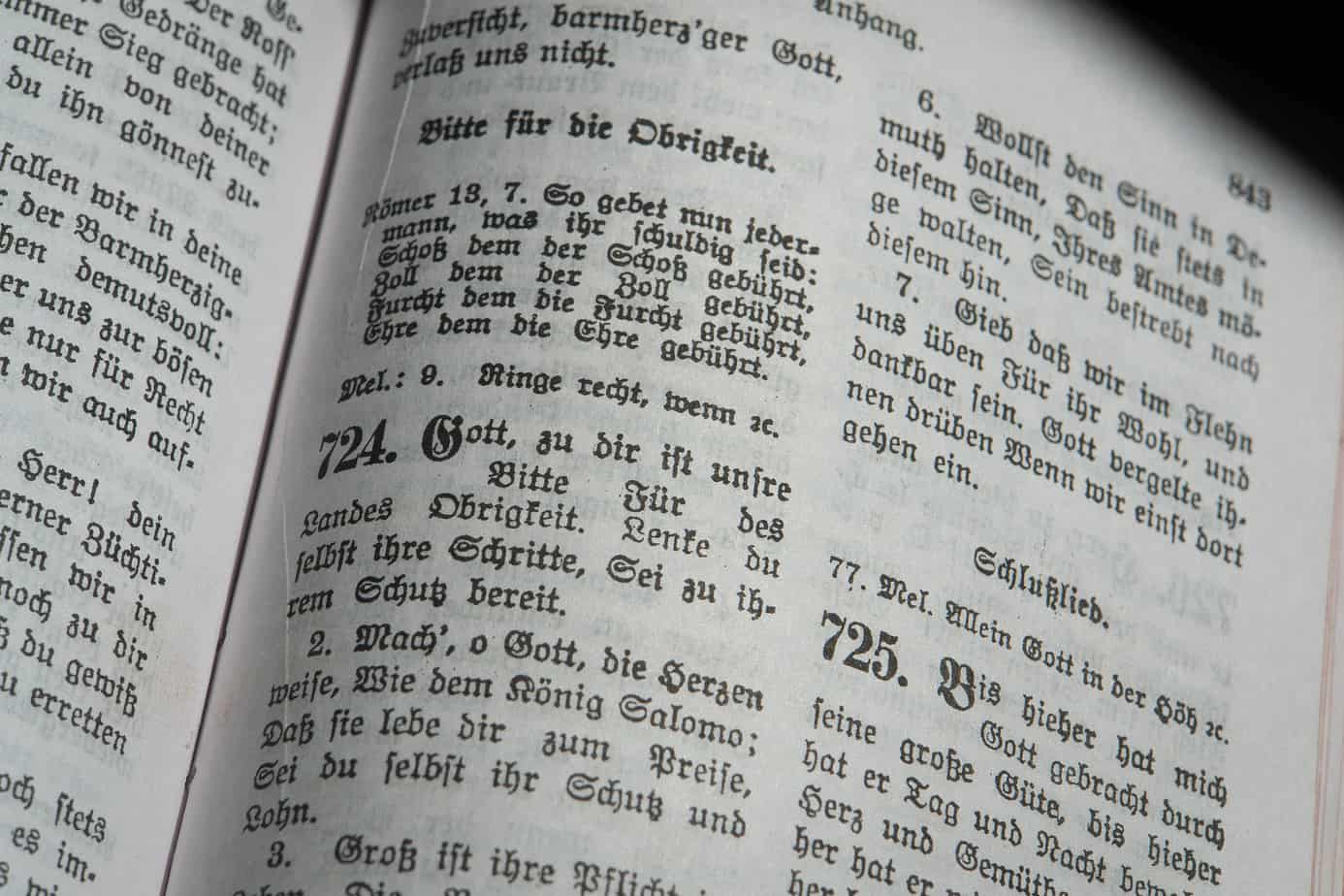

The church was an inconspicuous-looking building. The hall was divided into two sections: the left for the women, the right for the men, the latter section including a place to hang their hats. Their hymnbook has no notes, they sing bible texts without musical accompaniment. The service starts one hour after sunrise and lasts for 1.5 to 2 hours. They don’t have a Sunday school, young children stay at home and join their parents for church service at thirteen. Anna told us that the children go to school six months a year, from age six to twelve where they are taught about religion and the bible, and learn reading, writing and arithmetics, and German. Spanish and Guaraní are not taught in this colony.

After this visit they invited us to share lunch with them, a nice meal of rice and beans with chicken. Like Lisa and Frans, Anna and Johan were very open in sharing details about their way of life, a far cry from being the closed, narrow-minded people we expected them to be based on stories we had heard in Friesland. It showed – once again – how careful we should be about forming an opinion, especially without having met the people or having visited the place. – KMV

Read other stories from the road by clicking on the banner below: