Photography from Barbara Toy’s A Fool Strikes Oil and Travelling the Incense Route

“I travelled for the love of travelling. All too often these days people say they’re going to cross something like the Sahara Desert and all they want to do is get to the other side as fast as they can. That’s not me.” – Barbara Toy

Four-thousand feet above sea level, Barbara Toy sits beneath a large acacia tree in Northern Yemen, sharing a meal of rice colored with saffron, tuna, and onions with several rugged Bedouin from the local Yam tribe, two elderly pilgrims, her guide Hassan, and two lorry drivers. The group murmurs about four Bedouin killed the previous day by bombs dropped into a nearby wadi. Hundreds of pilgrims, en route to Mecca, bask in the shade, resting in groups amongst nearby rocks. Suddenly, the drone of a bomber plane breaks the desert silence. Toy glances at her Land Rover, hoping the reflection of the glass isn’t too conspicuous. “There was a sudden report of ack-ack guns from the neighbouring wadi,” Toy recalls in Travelling the Incense Route. “A second spurt, and almost immediately came the deafening crunch of bombs—and then there was silence.”

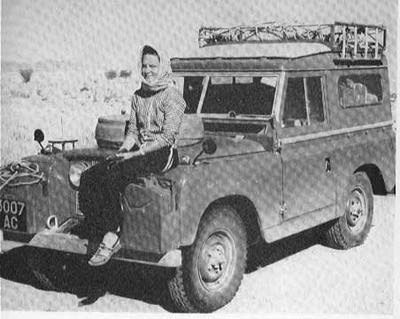

Toy’s mission was seemingly impossible: to follow the Incense Route from the Yemeni coastal village of Bi’r Ali north through civil war territory in Northern Yemen, driving north through Saudi Arabia, Jordan, and, finally, arriving in Damascus, Syria. It is unclear when this pioneer of overland travel undertook the journey in her 109-inch Series II Dormobile, but based on references in Travelling the Incense Route, it was likely between 1966 and 1967. When she arrived in the Yemeni city of Aden, Toy was without a Saudi Arabian visa (a nearly impossible endeavor at the time, especially for women), did not have a permit to enter “the Yemen,” and was without permission to leave the city of Aden itself. Meanwhile, the political situation was worsening every day, with few civilians traveling to the interior of the country.

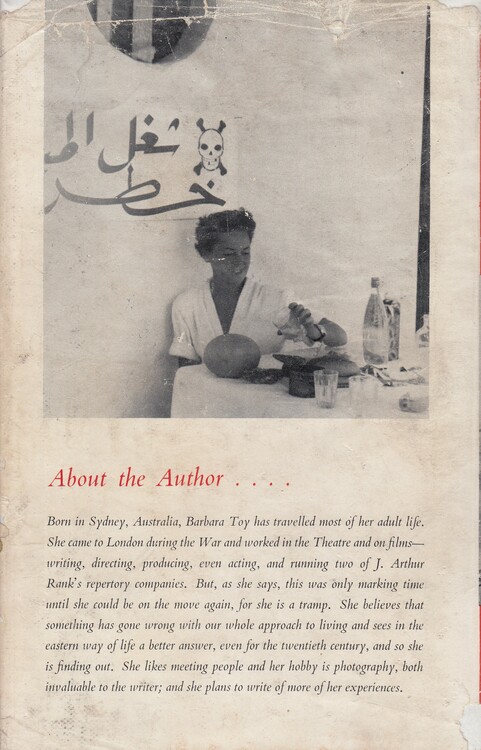

This wasn’t Toy’s first time traveling through the region. She was granted permission from Saudi Arabian King Abdulaziz to explore the country by Land Rover in 1953, making her one of the first women to travel solo through Saudi Arabia. An Australian-British theatrical director, playwright, and screenplay writer, Toy’s entry into the world of overland expedition came as a result of a bet made with friends in a London pub in 1951. “I suddenly found myself saying, ‘As a matter of fact, I’m off to Bagdad [sic] in a week or two,’” she told Australian Women’s Weekly. Toy bought a demonstration 1950 80-inch rag-top Series I Land Rover, named it Pollyanna, and spent the year traveling to Gibraltar to Baghdad and back to London. She embarked on various solo trips after that, including two round-the-world stints, and penned nine books before she died on July 18, 2001, at the age of 92.

Back in the East Aden Protectorate office, a young woman Toy describes as having “an intelligent face and beautiful hands” sent a signal off to the Saudi embassy in Jeddah, applying for a visa on Toy’s behalf. “There is no Saudi Arabian consul here and, as you must know, it is almost impossible to obtain visas for that country,” the young woman warned. “You certainly cannot leave without one.” As a response could take some time, Toy decided to follow the section of the Incense Route in Southern Arabia.

A keen history buff and Fellow of the Royal Geographic Society, Toy knew that the port in Bi’r Ali was a starting point of the Incense Route. “Along its devious course was carried ivory, tortoise-shell, indigo, gold, pearls, diamonds and sapphires, silks and spices – all the treasures of Africa, India and the Far East—and most important of all the sacred and mystic frankincense,” she penned. Camels transported incense from the source to the Mediterranean Sea. Because of its wealth in frankincense and myrrh, the area became known as Arabia Felix (Prosperous Arabia). Although the Incense Route was long abandoned by the late 1960s (sailing across the Indian Ocean provided a more direct route), both traces of its existence and written accounts remain.

Toy eagerly made plans—poring over maps, sharing three cups of sweet milky tea with the Sultan of B’ir Ali, and reuniting with her previous guide, Mubarak, for a trip to Ayadh. She longed to follow the ancient footsteps of the Three Wise Men, the Queen of Sheba, and the more modern tracks of British explorer Saint John Philby. Toy also gleaned much of her knowledge from English author Charles Doughty, who lived with the Bedouins in the area during the 1870s and wrote Travels in Arabia Deserta in 1888. All she needed was that elusive Saudi Arabian visa.

“No one but myself believed the journey north would be possible; that permission would be given,” Toy wrote. “But I did experience a shock, with excitement perhaps, as I read: ‘Received Jeddah today approval to pass overland.’” The catch? A feasible itinerary had to be approved by the Saudis prior to departure and a safe route planned through dangerous territory to the north. Toy’s guide, a soft-spoken young man named Ali Hassan, offered a solution. “I have a friend who is an agent. He will know the best way for you to go,” he said. “He arranges lorries taking pilgrims to Mecca for the Hajj.”

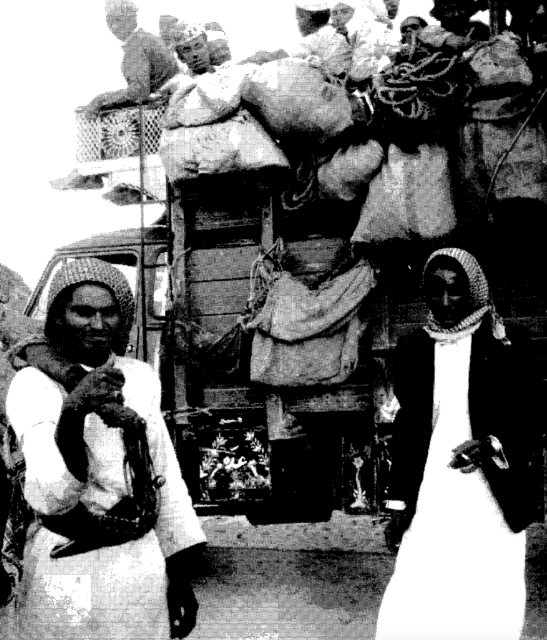

Loaded up with 60 gallons of petrol, Toy led the way as two overloaded lorries followed her Land Rover carefully through the dark night. The lorries carried between 90 and 100 pilgrims each. “My companions of the weeks to follow were piled to dizzy heights on top of the oil drums, boxes and their own bundles,” she wrote. “The sides of the lorries bulged with sacks of grain and rows of water skins.” Struggling through the sand, driver’s assistants used sand channels to keep the giant trucks moving. Eventually, it was decided that Toy and her Land Rover should lead the convoy, scouting for the safest terrain.

The group traveled by night, spending daylight hours having a wash, a rest, or gathering around Toy’s first-aid kit, which provided welcome remedies for the pilgrims’ blisters, cuts, headaches, and constipation. This was all done undercover. The track, in certain sections, was mined. “All the mines had been exploded by passing vehicles,” Toy wrote. “…experience in similar fields has taught me that one can drive over a mine once and the second pressure sets it off. We [prayed] we would not stick.”

The North Yemen Civil War broke out after Imam Ahmad ibn Yahyā’s death in 1962, beginning with a coup d’état carried out by revolutionaries who declared the foundation of the Yemen Arab Republic and dethroning the newly crowned Imam Muhammad al-Badr. Saudi Arabia, Iran, and Jordan supported the tribal royalist forces, while the Soviet Union and Egypt, under President Gamal Abdel Nasser’s rule, provided weapons and arms to the Republicans.

It was imperative for Toy to avoid the Republican troops at all costs, for “once having made contact with them I could not pass into Saudi Arabian territory,” she wrote. “What kind of propaganda would be made of it should they capture me?” There was a strong anti-British sentiment in the country, fueled by Nasser’s regular radio broadcasts. Not only was Toy at risk, but so were the 200 pilgrims making their way overland to Mecca, as well as the people of Yemen, who remained on both sides of the conflict. Fortunately, as the convoy neared the Saudi Arabia border, the worst dangers were over. “There was an easing of tension and a festive air about the pilgrims,” Toy wrote. The group could now travel by day.

Barbara Toy continued her travels along the Incense Route, sipping coffee with the emir upon entry into Saudi Arabia, continuing north with the pilgrims until Mecca, and presenting a letter from Prince Khalid at each gate. “For a foreigner to travel alone without such a document would be almost impossible,” she wrote. As long as Hassan was sitting in Land Rover’s passenger seat, she would not be conspicuous as a female driver, as the Saudis drove on the right. They passed brightly tassel-adorned Mercedes, Volvos, Bedfords, and Leylands that had come from as far away as Iran, Turkey, and Pakistan for the Hajj. Airplanes arrived every 10 minutes, and the population of Jeddah more than doubled in anticipation of the annual pilgrimage.

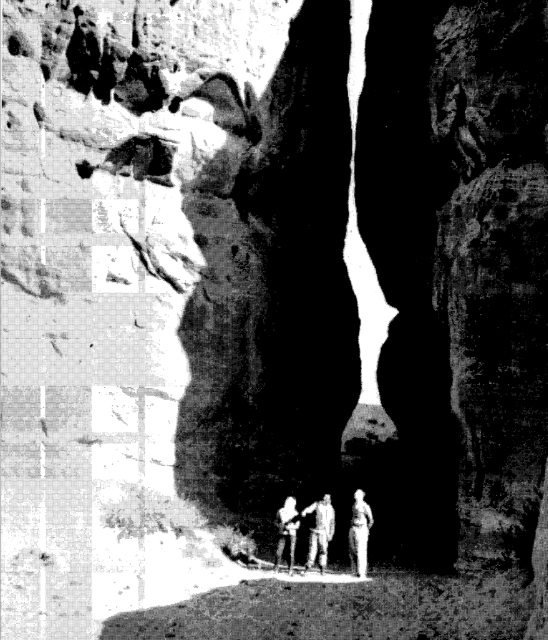

Following the Hijaz Railway, Toy passed bushy eucalyptus trees, becoming lost in a “maze of ridges intersected with shallow wadis, peaks and outcrops of sandstone.” She stopped to admire the Nabataean archeological site of Madain Saleh—a glorious city carved out of rose-colored sandstone. Eventually, the Gulf of Aqaba came into view, and Toy was met at the Jordan border by English-speaking soldiers offering tea. After climbing to admire the valleys of Wadi Arabia in Petra, stopping by the 13th crusader castle of Mont Real, and paying a quick visit to a renowned healer cum butcher in Amman for her chronic back pain, Toy arrived in Damascus, “surrounded by its beautiful orchards and gardens.”

Reaching the end of the Incense Route, Toy spotted the old Ottoman trading centre: Khan al-Zait. Merchandise surrounded her: rolls of carpet, bags of grain, and small wooden and tin boxes—frankincense and myrrh. “The scent of the spices followed me out,” she wrote, “and the great doors clanged shut behind me.”

Read more: Jeopardy and a Jeep :: Africa Conquered by Two Women Professors