Words By Ashley Giordano, photos from Jeopardy and a Jeep by Dorothy Rogers

During the summer of 1954, two American college professors named Dorothy Rogers and Louise Ostberg pulled their Willys Wagon into a mechanic shop in Tripoli, Libya. They had arrived from the North African desert, where they battled endless flats and ruined tire tubes in over 110° temperatures, their mouths dry and eyes bloodshot from wind that Rogers described as “liquid flames licking the face.” After 25,000 challenging miles from France to Algeria, crossing the Sahara Desert and jungles of the Congo to the southern tip of the continent, and heading back north through Cairo and along the North African coast, their current set of tires were arguably more patchwork than rubber.

It was in Tripoli that Rogers and Ostberg met four British fellows who told an enthusiastic account of a trip they were about to undertake. They called themselves the “Oxford-Cambridge Expedition” and were hoping to complete their first circuit of Africa. “They had all sorts of special equipment and expenses were being paid by the sponsors whose products they were using,” Rogers wrote in her travelogue Jeopardy and a Jeep. “When the young man who was telling us of their plans paused to permit suitable noises of admiration on our part, another party broke in: ‘And where are you two gals travelling?’”

Seven months earlier, the American duo rang in the new year by setting off from Cherbourg, France, in their brand-new Jeep Station Wagon and a copy of Trans-African Highways: A Route Book of the Main Trunk Roads in Africa clasped in their hands. The book recommended a car with good ground clearance, ample power, wood rather than steel body (due to extreme heat), and wide tires run at low pressure. Deciding against a French Savanne due to cost, Rogers and Ostberg settled on the Jeep (affectionately referred to as “Jeepo”) and never regretted it. “We learned to swear by our car, she said, “while other motorists swore at theirs,” Rogers wrote. The United States didn’t issue international license plates at the time, so Jeepo masqueraded under the guise of French tags.

Surviving a winter storm in the Pyrenees (“We missed a precipice by a mere millimetre during a blizzard,” Rogers wrote), towing several cars through the snow, running out of fuel at midnight on a remote mountain pass in Southern Spain (Rogers: “Have you ever tried to contrive a funnel from paper?”) and successfully bribing an officer with a few greenbacks to make the ferry to Morocco, the pair rolled Jeepo onto a boat bound for Africa.

The continent that Rogers and Ostberg landed on in 1954 was quite different from Africa as we know it today. They traveled in a time where apartheid law ruled South Africa, the Mau Mau uprising was on its way to freeing Kenya from British rule, while Tunisia remained under curfew as French tanks, trucks, and soldiers cluttered the roads until the country’s independence was granted shortly thereafter. The Second World War had highlighted the problems of racism, and a wave of decolonisation in Africa was to follow.

Passing the snow-capped Atlas Mountains and caramel-colored sand dunes of Morocco and Algeria, the women arrived in Algiers, where they prepared for a multi-day crossing of the Sahara. A $22 liability policy purchased from a local company covered the entire African expedition. The duo also signed a breakdown contract with the Touring Club of France, which required all drivers attempting to cross the Sahara to notify the local French commandants along the way, who in turn wired messages to officers at each upcoming oasis of the traveler’s expected (and hopefully safe and successful) arrival.

The breakdown contract was no joke. Rogers and Ostberg often drove during the night, straining to see the track, passing vehicles so marked by time that, according to Rogers, “only the skeleton remained.” Between the sandstorms, unmarked tracks, and old trails, they often feared they were lost, and more than once were quite sure of it. “Louise confessed that it was not so much the idea of being lost that bothered her as the remarks that people would make when they discovered our bleached bones,” Rogers wrote. “Well, two women! What could you expect? The fools deserved their fate!”

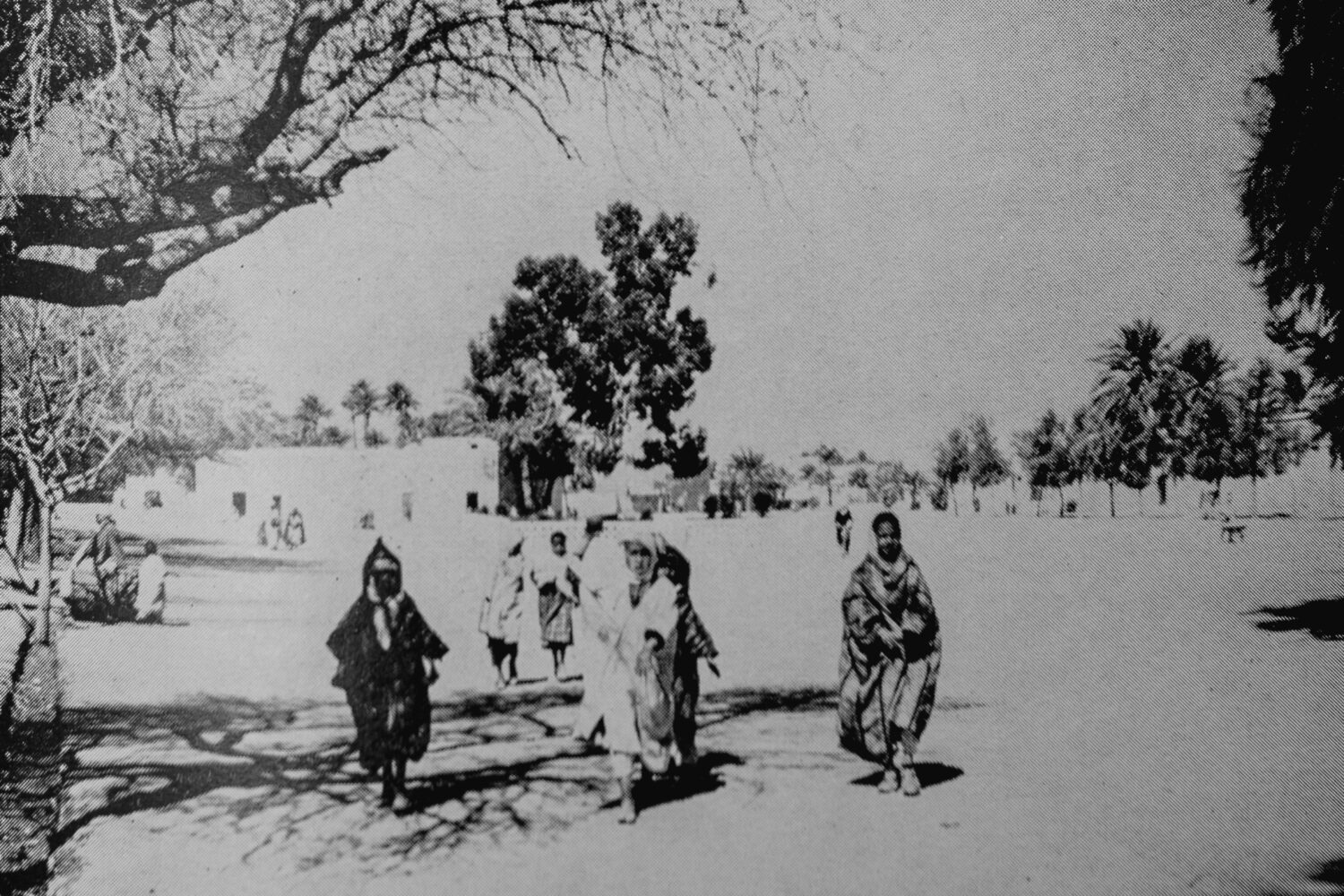

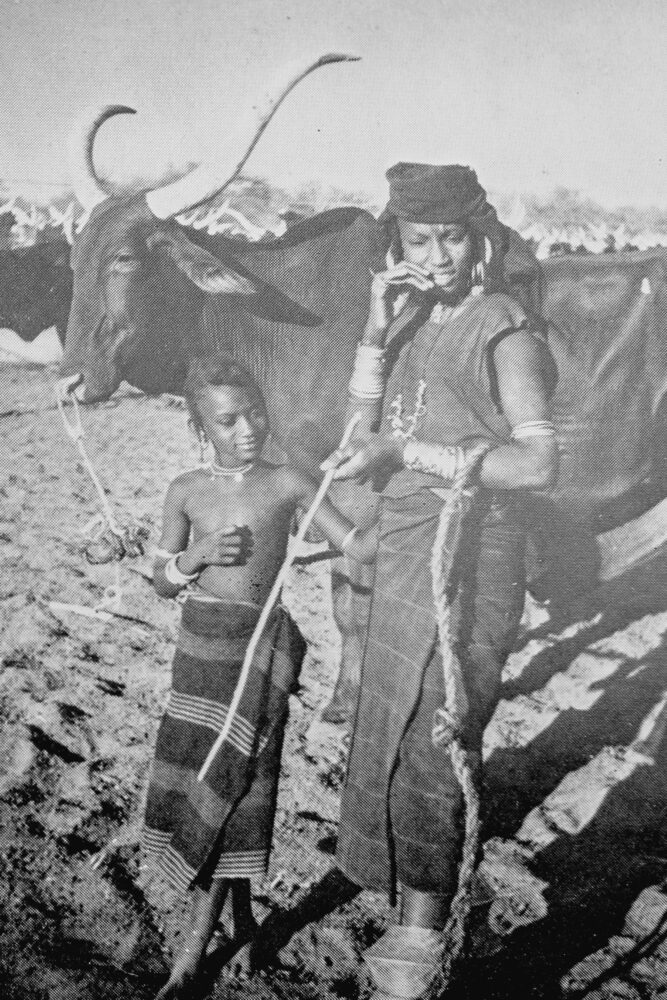

Through sand goggles, dust masks, and open windows, the two spotted caravans of up to a thousand camels accompanied by women clothed in bright colors, who wore “ornaments in their pierced noses, and heavy bands of metal shackled to their ankles.” They ate sticky-sweet dates from flourishing palms, ploughed through the desert at 20 mph, and camped at old fort-turned-rest houses called borjs, which were frequented by Arabic-speaking truck drivers throughout the Sahara. After thousands of driving miles from Algiers through Zinder, Niger, a border official greeted the ladies in English: “Welcome to Nigeria. Drive on the left.”

Nigeria was the largest British colony in the world at the time, and thus rest houses and municipal campsites could be found not only there but also along the main routes of central Africa. The rest houses were small but basic structures used by European administrators on their “tours of the bush.” The women enjoyed these spots as they provided an opportunity to interact with others—for better or worse. “The only unpleasant feature of otherwise very cordial chats was one inevitable comment that we evoked,” Rogers wrote. “‘What? Two ladies?? Alone?? No MEN along???’ Are women to be thought of as infants too feeble to get around alone?”

Successfully crashing the border of Cameroon without visas, Rogers and Ostberg continued through the howling winds and tropical storms of French Equatorial Africa (known today as Chad, the Central African Republic, the Republic of the Congo, and Gabon) and into what was formerly known as the Belgian Congo. Through flourishing tamarind and fir trees, the pair caught glimpses of locals dancing— “not the stylized affairs organized for tourists,” Rogers noted, “but primitive rhythms in tune with the heartbeat of the jungle.” Congolese men carried spears and hatchets, and a few carried firearms. “Elsewhere in colonial Africa,” Rogers wrote, “the practice [of Africans carrying firearms] has been strictly forbidden.”

Suspected as spies while exiting the Congo (allegedly women spies had been reported in the vicinity), the duo continued through Zambia and Zimbabwe (known as Northern and Southern Rhodesia prior to independence) towards South Africa. Inquiring about a nearby camp spot in the town of Louis Trichardt, a local gas station attendant referred Rogers and Ostberg to the circus grounds of a Dr. Fritz, where they spent a restless night camped between a lion cage and a pen for trained ponies. Finally, on April 25, 1954, the pair reached the southern tip of the continent, where the swirling waters of the Indian, Atlantic, and Antarctic oceans meet. They had arrived at the Cape of Good Hope.

“While it inflated our egos to perch on that cliff and realize that we had achieved land’s end, it also chilled us to the bone. Even Ward’s best orlon underwear could not stop those chilling winds so we scrambled down… to our car below,” Rogers wrote. Shooing baboons from the Jeep, the women started the long journey north. “It was a rough, hard life we led,” Rogers noted. “All day we careened precariously down a difficult track, pausing briefly for visits into villages and sorties into the forest. Our clothes were dank and sweaty; our faces crusted with grime. Nevertheless, we relished every instant of this magnificent adventure and vowed it was worth it even if we never emerged alive.”

Then there was the issue of whether to buy a gun (or not). Opinions varied, but an official at the American consul in Zimbabwe endorsed the idea: “Everyone who goes to Kenya these days takes a gun!” A booklet from the Royal Automobile Club in Cape Town also recommended carrying a revolver or pistol in various parts of North Africa and Egypt due to “bandits.” Ostberg was against the idea, arguing that by carrying a gun, “one invites the other person to kill by whatever means he can.”

Eventually, the women visited a gunsmith, purchasing 25 rounds of ammunition and a “neat little job.” However, with the pistol came a variety of red tape and paperwork at each border, and after Egypt, they found it easier to smuggle it. “That gun gave me so much trouble I wished later that I’d taken Louise’s advice,” Rogers lamented.

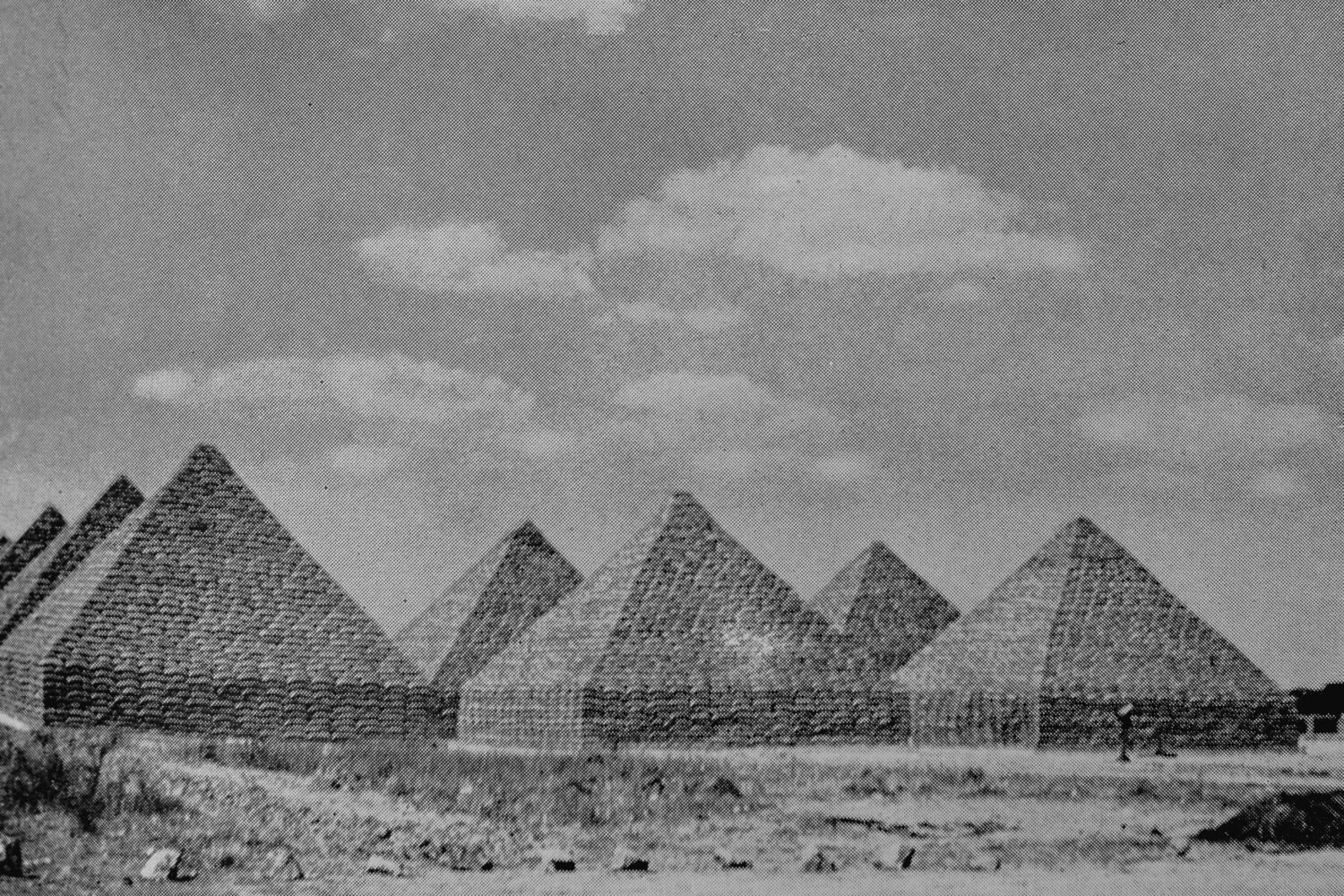

With Mozambique, Eswatini, Malawi, Tanzania, Kenya, and Uganda behind them, Rogers and Ostberg entered Sudan, where they boarded the Rejaf, a steamboat born in Mississippi and raised on the Nile. The occasional cluster of grass huts, herds of elephants, and strong cup of Sudanese coffee shared with the schoolmaster of a nearby village added interest to the flat green landscapes of their eight-day sail. The journey continued via rail, by barge containing 350 bulls, and, eventually, by land into Egypt. Cities were crowded compared to the remote villages the women had visited, and the desert was littered with relics of the war, including tanks, weapons, carriers, and rusty fuel cans. “We would have bathed in the sea,” Rogers noted, “but had been warned that unexploded mines had been cleared for only a short distance to either side of the road.”

With the end of the trip in sight, the pair undertook one final push through the heat of the North African desert, which, according to Rogers, “penetrated every pore and threatened suffocation.” They travelled “minus top clothes” to keep cool. After passing huge sand drifts and Bedouin camps, struggling with a badly cracked wheel, and one flat tire after another in the rising heat of the desert, Rogers and Ostberg eventually arrived in Tripoli.

As they prepared for the final leg into Tunisia (despite rumblings of revolution), Rogers and Ostberg replied to the Oxford-Cambridge lads’ inquiry about their travels. “We just completed making the circuit of Africa that you are planning…” began Louise. Their reaction? “The gentleman faded away as quickly as possible,” Rogers wrote, “probably deciding that they had imagined what they had just heard.”