Lead photo courtesy of Through Algeria & Tunisia on a Motor-bicycle

“When the wandering spirit stirs him, lucky is he who can yield to the lure. There are probably few people, to whom travelling is even remotely possible, who have not felt the longing to feel and see the romance unfolded by travellers’ tales. To all such this book is written.” – Lady Warren, Through Algeria & Tunisia on a Motor-bicycle

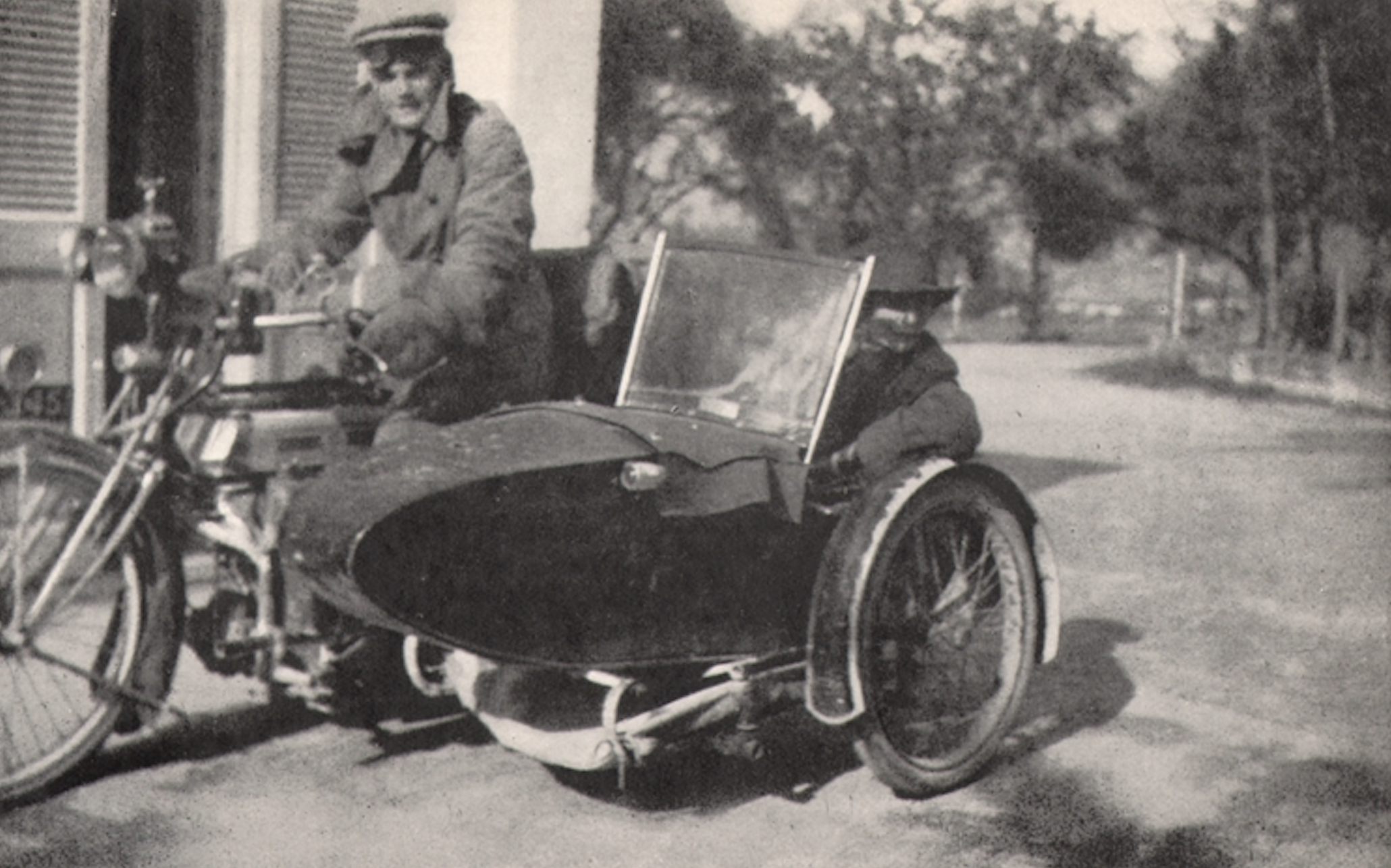

After enjoying a hearty lunch at one of the largest Roman stone ruins in the world, Lady Warren and her travel companion, “P.” left the El Djem amphitheater, departing north to Sousse, Tunisia. Thunder, lightning, wind, and hail crashed, cracked, and swirled above the pair, who rode a 4-horsepower, belt-driven 1918 Triumph motorcycle with a Dunhill sidecar along the newly metalled road. Lady Warren was tucked into the sidecar, where she frequently wrote notes that eventually formed her 1922 travelogue Through Algeria & Tunisia on a Motor-bicycle. “P. was in greater spirits, and we went faster than ever we had done before,” she said. Suddenly, P. remarked, “Something desperate has really happened,” and the sidecar became airborne, flipping over the motorcycle as they plunged into a ditch, landing upside down.

Aside from what she wrote in Through Algeria & Tunisia on a Motor-bicycle, very little is known about Lady Warren. Even less is known about her travel buddy, P. However, we do know that Lady Warren lived in London, spent three weeks driving through Algeria and Tunisia with P. in 1921, and that she continuously searched for hotels with a bath and preferred to eat with cutlery. In many ways, she was quite typical of the average British female traveler and travel writer at that time; at the same time, she was also very different.

The beginning of the 20th century saw modern tourism taking hold in Britain, where tours organized by tourist agency Thomas Cook & Son were all the rage. Before the Industrial Revolution, leisure travel by Europeans to Northern Africa was mainly accessible to the aristocratic elite. But the development of transportation such as railways, coaches, and steamships generated a drive for vacation time and provided a cheaper and safer means of travel over long distances. Women took advantage of these changes, traveling farther than ever.

North African countries such as Algeria, Tunisia, Morocco, and Egypt became desirable European holiday destinations. Thomas Cook’s Practical Guide to Algeria and Tunisia (1908) and Conty’s Guide Bleu French travel guides provided practical information about excursions to the area, making it convenient to include these countries in tourists’ itineraries. But Lady Warren and P. desired independence. Initially, they considered traveling by boat, train, or public or private car, which “sounded thrilling at first,” until “one realized that it meant being tied to one’s conductor, the transatlantic company who have flooded the route with tourists.” The more they considered the idea of Algeria as their starting point, “the more it pleased us…[and] the more determined we were to be independent.”

The motorcycle and sidecar combo was P.’s idea. Lady Warren admits that her “spirit shrank” at the prospect. Only once or twice had she ridden in a sidecar, with “blenched face and turned-up toes… [as we] whizzed round corners at what felt like the peril of my life. P. swore he wouldn’t drive more than 5 miles an hour (they hit 40 at one point) or take them down winding mountain passes (welcome to Algeria’s Atlas Mountains!). After some convincing (and unaware of what lay ahead), Lady Warren acquiesced, purchasing a hood for the sidecar to “keep the sun off my delicate person,” goggles for dust and glare, a mica windscreen, and plenty of spare parts. Into the sidecar went “loose things, books, cameras, field-glasses, sketching materials, fur coats, overcoat, dust-coats, mackintoshes, and lastly myself.” Behind the seat, they placed a kettle and stove, biscuits, chocolate, and tea. “It seemed absurd,” she wrote, “to have 15 boxes, bags, holdalls, and bundles”—minimalism be damned!

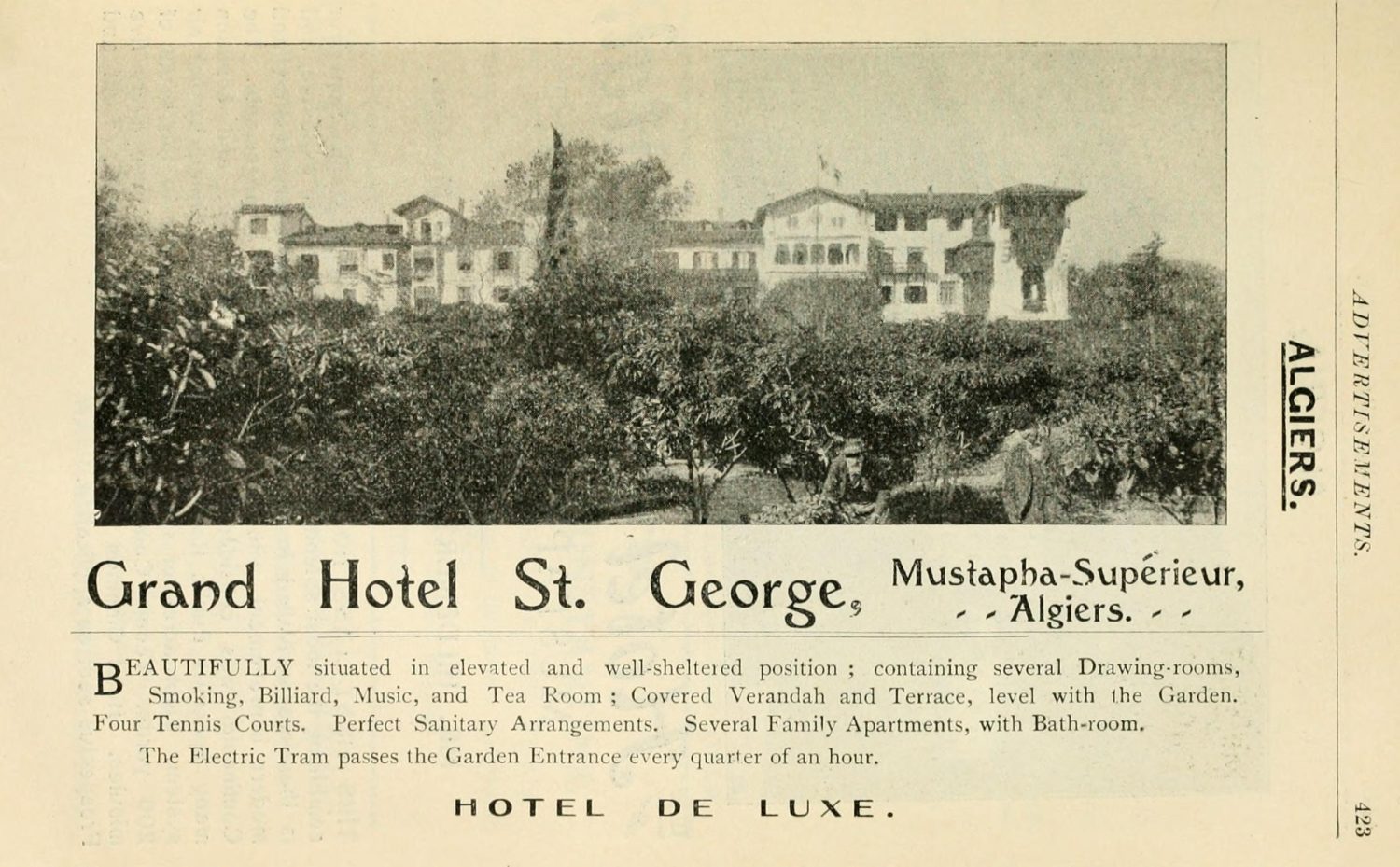

In the early morning of February 15, 1921, the pair boarded the China bound for Marseilles and eventually settled onto the Timgad, which would take them across the sea to Algiers. “It was afternoon on a winter day, the sun thinking of setting, the sky blue at the zenith and silvery gold on the horizon east as well as west,” she wrote. However, not everything was so magical. “As we drew nearer, the town itself lost all its magic qualities and revealed an ugly sameness of barrack-like flat-topped modern French-built hotels and houses…” Eventually, they arrived at the five-star Hotel St. George (which still stands today as Hotel El-Djazaïr), surrounded by a lush botanical garden. Lady Warren’s room featured a window overlooking the bay, and a view of the sea, “blue as indigo, threw splashes of white foam on the yellow sand.” After dinner, she and P. walked in the garden and listened to some “very excellent” classical music played by the hotel orchestra. Not a bad start to the trip.

As they departed from Algiers the next morning, Lady Warren shared her fears about traveling in the sidecar, which would continue throughout the trip. “I had visions of various tragic endings to our beginning,” she notes. But the scenery, marked with wooded hills in the distance and “great spaces of vivid magenta pink and bright gold flowers,” raised her spirits. Through towns marked by French colonialism, over twisting mountain roads, past olive trees, and the lands of the Kabyle people, they drove on, often arriving after dark. “In all our tour there was hardly a day that we were not benighted or had to race home in the last vestige of twilight,” she writes.

In the Forward to Encountering Difference: New Perspectives on Genre, Travel and Gender, Carl Thompson of the University of Surrey writes, “…we are all moulded to some degree by the languages, histories and cultural practices we inherit and inhabit. Wherever they may wander in the world, travellers necessarily carry with them a gaze formed by their upbringing and background, and by membership of diverse, intersecting communities and identities—of nationality, family, class, gender, sexuality and so forth.” This is evident in Lady Warren’s travelogue, as she touches on the weather conditions, landscapes, political and historical backgrounds, and the beliefs, practices, and manners of others—all of which were typical themes featured in women’s travel writing in the 1920s.

But we also see differences in Lady Warren and P.’s travel styles. “…Then I knew that P. and I had started with different ideas. Mine that the bus was a means of travel and seeing things, his that travelling was a means of trying the bus; mine to stop in the quaint places, his to do as many miles a day as possible,” she writes. At one point, like a couple paddling a tandem kayak (often aptly referred to as a “divorce boat”), they get into a heated argument. “He pretended he did not hear me. P. said he would go back, in the sort of tone one uses to an idiot, a drunken man, or a tiresome child to humour it or them. Quite a bright and sparkling dialogue took place at the top of our voices…” Like most travelers getting into the swing of things, she admits that they were “new to it and over-did it” and the “vicissitudes of the weather” and overtiredness accumulated over the initial long days of travel. They began their marathon with a sprint.

Lady Warren and P. continued, from Fort National to a guided tour in the desert via Touggourt, motoring through Constantine, soaking in the waters of the Hammam Meskhoutine, and into Tunisia, where the pair found themselves in a roadside ditch, and fortunately, relatively unharmed. “It seemed ages before I felt the ground with the back of my head, and I thought my neck was broken.” She knew how heavy the motorcycle was and, afraid, hesitated to ask P. if he was okay.

Finally, she felt him stir. “Are you dead?” she asked feebly. “No, are you?” Bruised and shaken, they rolled out into 6 inches of mud, surveying the damage. The sidecar frame had parted, revealing a clean break in one of the arms. Lady Warren walked to a small railway station three miles away for shelter while P. separated the motorbike and sidecar. Eventually, they hired a motorcar, P. driving separately on the Triumph, and transported the wreckage back to London. “The remains followed by steamer,” she wrote, “and, wonderful to relate, renewed and rejuvenated, the whole ‘bus’ is… as it was before the start, waiting, and vainly I fear, for us to do it again in some other country.”

Did Lady Warren head off again, gallivanting through another country? If so, there is no evidence to suggest that she published another book. Her publisher, Jonathan Cape, saw the demand for travel books after the first World War, and Through Algeria & Tunisia on a Motor-bicycle made the 1922 list. Today, she is remembered, primarily by scholars, as one of the few women who wrote about their travels through North Africa in the early 20th century. As far as I know, she is the only one to have written her tale from behind the windscreen of a sidecar during this time.

Another question remains unanswered—who is P.? Readers aren’t introduced to him until page 12. There is no evidence that the pair are married, and Lady Warren is silent or vague on the details of their relationship. It appears she made her way through London alone but must have met with P. sometime before they boarded a boat bound for Marseilles. They always stayed in separate hotel rooms, ship berths, and once divided a room in half with screens as it was the only one available. Finally, P. and Lady Warren went their separate ways at the end of the trip. “The train swallowed me up London bound. P. started for Germany via Paris, and all was over.” Was P. her brother? A friend? A relative? Perhaps we’ll never know.

Summary, from Through Algeria & Tunisia on a Motor-bicycle:

Dunlop 2.5- x 26-inch tyres

4 H.P. Belt-driven, 1918 “Renovated” Triumph, with light Dunhill side-car

Weight of machine, 310 lbs.

Weight of passengers, 260 lbs.

Carried 2 suitcases, 3 gallons petrol, ½ gallon oil, spare tyres and parts

Total weight about 630 lbs.

Total Mileage, 1,707 miles (1,589 miles with side-car)

Total Petrol consumed, 27 ¼ galls.

Total hours travelling, 104 ¾

Total hours on road, 87 ¾

Average speed, 19 m.p.h

Average miles day, 99

Average hours travelling per day, 6 ¼

Our No Compromise Clause: We carefully screen all contributors to ensure they are independent and impartial. We never have and never will accept advertorial, and we do not allow advertising to influence our product or destination reviews.

Read more: The Rugged Road – A Sidecar Journey from London to Cape Town