Back in the 1970s, during the dark, torrid days of Apartheid, South Africa fought a Cold War proxy conflict against a collective of international communists in Angola. Due to the oppressive, racist regime and the policy of “separate development,” international sanctions were imposed against the country, limiting the average consumer’s options for purchasing everything from washing machines to blue jeans to cars. In 1976, in response to the sanctions, General Motors South Africa (GMSA), likely inspired by and hoping to contribute to the arms sector (the South African government built their own war machines via arms manufacturer Armscor, which did a decent job, surprising the world) had the bright idea to create a “homegrown” off-roader. An automobile built from South African materials and ingenuity, a capable truck to take on the harsh African landscape!

Image by Car Mag

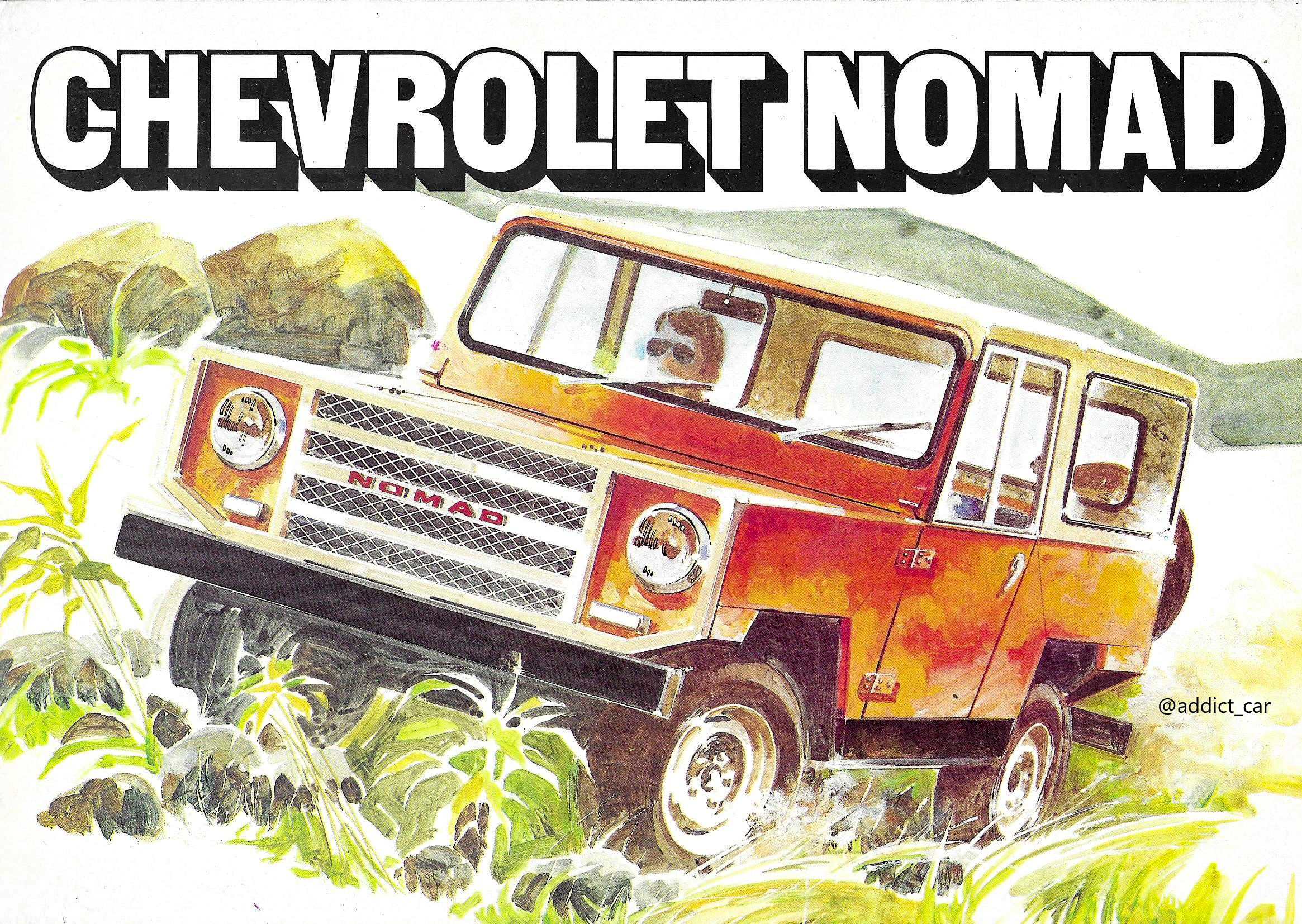

The concept was relatively simple—build a vehicle to rival the Series Land Rover and do so on a shoestring budget, with minimal production costs, to produce an affordable “open body” utility vehicle. Dubbed the Nomad, GMSA offered the model line with rear-wheel drive only and powered by a 2.5-liter inline-four that produced 102 horsepower (76 kW/103 PS) at 4,000 rpm. Paired with this monster engine was a 4-speed manual Borg Warner transmission delivering the power (I use that term loosely) to the limited-slip differential-equipped rear axle, a Holden unit from Australia. The sparse dashboard housed a coolant gauge alongside the headlight dial, fuel gauge, and speedometer from VDO instruments in Germany. The United States supplied a Rochester carburetor, and the engine itself was designed by Chevrolet and was shared by the locally-produced Chevrolet 2500 and others.

While the Series Land Rover was quite beautiful from any angle, achieving near-perfect symmetry via a design that reflected the principle of thirds, the Nomad was, in a word, chunky. The panels were all flat, every edge at 90 degrees, the removable doors angular, and the rear door a square of sheet metal.

Image by Car Mag

The windscreen folded flat, and GMSA sold the vehicle with a soft canvas top or an equally angular fiberglass canopy and no heater. The vehicle’s flat steel fenders could be easily replaced in the case of an accident, and, I have to admit, the car can generously be described as charming, but not when parked next to a Land Rover. The interior design was purely practical and spartan, a mirror of the exterior. A bench seat could fit three, and there was no rear seating; the designers diligently omitted every possible creature comfort, and the rear load area very closely resembled an empty, antique steel toolbox.

The Nomad featured a short 82-inch wheelbase (six inches shorter than the 88-inch Series Land Rover) and boasted 10.4 inches of ground clearance. The undercarriage was fitted with a sump guard and a built-in box-section grille guard to protect the radiator and headlamps. It seemed to check all the boxes for an off-roader, but there was one severe, fatal flaw, as I would discover.

At the tender and financially challenged age of 24, I decided that humanity generally irritated me and that country life was the way to go. I had found a house to rent on a farm outside Johannesburg. I was on the lookout for a rugged vehicle with which to explore the countryside, brave the elements and eventually head out for weekend camping trips when my newborn son was old enough to rough it a bit. I should have saved my pennies and waited for the perfect little Land Rover to come along, but instead, I convinced myself to buy a cheap-as-chips Nomad, which I had seen parked beside a rugby field, for sale, in Pretoria.

Image by Curbside Classic

Admittedly, I knew nothing about vehicles other than how to drive and change tires, and I knew few people who could advise me about purchasing an off-road vehicle. The Nomad looked ready for action; it had vaguely all-terrain and fully inflated tires and came with a fiberglass canopy; I drove it home one late winter afternoon and arrived blue with cold. For the next few months, I tinkered on the Nomad, which, surprisingly, turned out to be a reliable vehicle that always started and ran well as I bumbled around the farm and took weekend drives into town for supplies. It was fun to drive, and my affection grew for the little box on wheels. My fondest memory is of a warm Saturday morning when I picked up an elderly Zulu hitchhiker. He played his tinny, homemade guitar and raised his voice to sing over the rumble of the tires and grumble of the engine as we rattled down the road, the fiberglass roof removed.

Summer arrived, and with it, the Highveld storms that regularly flooded Johannesburg and the surrounding areas. The farm on which we lived was accessible by three roads, one of which crossed the Jukskei River and featured a submerged concrete “bridge,” the other two roads were usually cut by the annual flood waters. When it rained for days, the farm would become an isolated island, and only 4WD and off-road vehicles could brave the deep water. The Jukskei was often too deep to attempt, even with a Defender or a Toyota Hilux. I had no fear, as we owned an off-road vehicle, or so I thought. One afternoon I was driving a farm worker back to her house and had to cross one of the rivers. I stopped at the water’s edge and waited to see if any other vehicles could cross; eventually, a Toyota Land Cruiser arrived and slowly plowed through the 200-foot-wide river. Emboldened, I set off slowly in his wake and only made it halfway before the engine spluttered and died, the interior flooding with water. Okay, so no good for water crossings, perhaps that was driver error, but more likely, the fan had sprayed water across the gasoline engine, soaking the spark plugs and distributor. A kind old farmer soon arrived with a tractor to rescue us.

Image by Key Military

A few weeks later, the weather was great, and I was driving home from work; the floods had found their way to the sea, and I drove contently towards a spectacular African sunset. On a flat section of the road, a massive bang and jolt ripped me from my thoughts; the Nomad dipped sharply to the left and ground to a stop in a cloud of red dust. My wife and I, shaken, stepped out to investigate. What we found was the reason why the Nomad is, most likely, the worst off-roader ever built. With chalky mouths, we left the Nomad on the side of the road, returned the next day with a replacement ball joint, and performed our very first “bush repair.” Yes, the wheel and suspension on this “off-road” vehicle were held together by a single ball joint! A few months later, I took the Nomad for a drive to a small abandoned quarry where I intended to have some fun tackling obstacles. Ten minutes after arriving at the quarry, I drove over a bump, and once again, the front end face-planted into the red dirt. I was able to reconnect the front suspension using a bottle jack, a door hinge which I happened to be carrying in my toolbox, and a few large nuts and bolts. I repaired the Nomad but never trusted it again, and it never took us on epic camping trips.

Image by Car Mag

In an attempt to produce a cost-effective off-roader, GM forgot the defining principles of off-road vehicle design. An off-road vehicle must have, at least, a robust suspension and sturdy axles and should certainly not be equipped with the flimsy independent front suspension borrowed from a town car! The Nomad’s independent front suspension, rack-and-pinion steering system, and front disc brakes came from the Chevrolet 1900. The rear axle, leaf springs, and rear drum brakes originally graced the Chevrolet 3800, both family sedans. Who on earth thought that was a good idea? Indeed at least one of the GM engineers must have had the gumption to stand up to the accountants and scream, “No, that’s just stupid!’. If they did speak up, no one listened, and what could have been a decent off-road vehicle instead became a complete waste of investment, manufacturing, marketing, and consumer cash. Once unleashed upon an unsuspecting market, the Nomad soon gained a reputation for having a dry spaghetti front axle. GMSA eventually listened and upgraded the front axle, but the damage was done. For 1976, GMSA assembled approximately 2,400 Nomads, with sales of the model line later falling to 250-300 annually; it was discontinued entirely in 1980.

Image by Car Mag

I happily sold the Nomad without hesitation and at a loss. An exuberant mustachioed man and his son came to inspect the vehicle and took it for a test drive; there are a few people, even to this day, who love the quirky Nomad. I waited, leaning smugly on the hood of a V8 1989 Land Rover 110, you know, a genuine off-roader with solid axles! The man arrived and told me that the Nomad would run rings around the 110; I agreed and added, “until the front axle fails.” He laughed dryly; I laughed wisely, he paid, I chuckled with relief, and he left with the box of disappointment. Good riddance, Nomad!

Why do I miss you?

Our No Compromise Clause: We carefully screen all contributors to ensure they are independent and impartial. We never have and never will accept advertorial, and we do not allow advertising to influence our product or destination reviews.