Photography by Bristol Foster, Robert Bateman, and Erik Thorn

It all began with birds. Birds near Toronto’s Forest Hill, to be exact. Back then, the nearby ravine and creek were thick with vegetation and towering willow trees, offering endless opportunities to identify warblers and flycatchers, blue jays, and thrushes. At least, that’s how it was for Bristol Foster and Robert Bateman, two young Canadians with an early appreciation for all things nature and wildlife. As teenagers, Foster and Bateman joined the Junior Field Naturalist Club at the Royal Ontario Museum, where their lifelong friendship, round-the-world trip, and the legacy of a 1957 Series Land Rover officially took flight.

Coincidentally, my interview with Bristol also begins with birds. This time, however, he’s referring to the ones perched near his home on Salt Spring Island, British Columbia. “They’re well fed,” he reassures me. The nonagenarian is a naturalist, conservation biologist, and documentary filmmaker with a PhD in ecology. He co-wrote the definitive book on the giraffe, spent five years in Kenya leading a graduate student program in wildlife ecology, and acted as director of the Royal British Columbia Museum and the British Columbia Ecological Reserves Program. This is an abbreviated version of his CV, by the way.

Throughout the winter months, Foster rings up his longtime chum, 94-year-old Bateman, who also lives on Salt Spring Island, to chat about the latest and greatest. Although he’s received international recognition as an acclaimed wildlife painter, Robert Bateman is more of a household name in Canada, where he has received numerous honors, awards, and 14 honorary doctorates, including Officer of the Order of Canada. Robert’s storytelling talents were evident during our interview, as he recalled scenes in crystal clear detail from the 14-month overland trip he took with Bristol in 1957. The pair picked up a Series I Land Rover, the now-famous “Grizzly Torque,” at the Solihull factory in England, setting off on a 60,000+ kilometer adventure through Africa, India, Southeast Asia, and Australia.

While the Brits, Americans, and Australians celebrate their contingents of early overland explorers, we Canadians have our legacy of heroes, too. To travel in time with Bristol Foster and Robert Bateman into the late 1950s, peering into a world that no longer exists, is something I’m truly grateful for. Plus, I learned a thing or two about the importance of birds along the way.

Although you didn’t know each other very well, Bristol suggested the round-the-world trip in a Land Rover. How did you react?

Robert: Although he’s a little bit younger than me, Bristol has been a leader in many ideas, including this trip around the world. He had gotten his MA and was going to get his PhD, but he came up with the bright idea to go around the world before getting settled into his PhD, which was going to be quite a time commitment. Obviously, it’s a dumb idea to go alone on an expedition, and he didn’t know me very well, but he knew me a little bit, and I was available.

He said, ‘How would you like to go around the world in a Land Rover?’ I said, Well, gosh, I don’t know. I’ve got this job, and so on. Not only did I not have a wife, I didn’t even have a girlfriend. I was a high school teacher in Richmond Hill, Ontario, but in those days, there were 10 jobs for every teacher. You could get a job anywhere, anytime. I knew if I took a year off, it wouldn’t make any difference.

Bristol said, ‘If you can think of five good reasons why we shouldn’t go around the world, I’ll accept it. Otherwise, we’re going.’ He called me back the next week, and I said, I can’t think of one good reason why we shouldn’t go. So that’s how it all got started.

How did you two meet?

Robert: We were both Toronto boys and got to know each other at a naturalist club at the Royal Ontario Museum. We called ourselves the Intermediate Naturalist Club. There were the juniors (which I was too old for), and we considered the seniors a bunch of old fogies. They weren’t, of course, but we were teenage boys, and we thought we were hot stuff and much more active than those old seniors would be. So, we formed our own club, and that’s where I met Bristol.

Bristol: Robert and I worked together for a summer studying mosquitos in Churchill, Manitoba, on the edge of the Arctic. We had a great time.

How did you prepare for this multi-continent expedition?

Robert: Bristol picked up the Land Rover at the factory in Solihull, England, and took a course on driving and how to take [the vehicle] apart and put it together again. Literally, they had these long tables covered with white tablecloths and the Land Rover all in bits and pieces—you know, the differential and the steering rods and everything all there. And then you had to put it back together again.

Bristol: We had this new Land Rover, so we went here and there to try it out. The back doors had to be rebuilt because they came down too low, and if we were going over bumpy roads, which, of course, we were, the back doors would hit the ground and bend. Pilchers of London made the body, and they gladly fixed the doors by cutting off the bottom 6 inches and raising them. Pilchers also put a metal cover on the roof because we had a third person come with us across Africa, Eric [Thorn], a fellow birdwatcher who we knew from many years ago.

Why did you choose a Land Rover?

Bristol: We wanted a superior vehicle because we knew some of the roads were really bad, especially in West Africa. Land Rovers seemed to be the most adapted to hard driving. We didn’t know if a Jeep would get through, but we knew if anything, a Land Rover could—and it did.

You eventually landed on a 1957 Series I Land Rover named Grizzly Torque. Where did the name come from?

Robert: Torque was for the vehicle’s might, and Grizzly was after a bear in Walt Kelly’s comic strip [Pogo], a series that Bristol and I both collected and admired.

How did you decide the route?

Bristol: Originally, we were thinking of crossing the Sahara from Algeria or Casablanca, somewhere along the north coast. But in 1957, there was a war going on in Algeria, Egypt, and North Africa, which generally wasn’t very safe, so we had to get on a freighter and ship from Liverpool to Ghana, West Africa. That’s where we started our drive. Unfortunately, we missed the Sahara.

[The route] was partly based on where the boats go and partly where we wanted to go. We decided that we wanted to cross Africa through the tropical rainforest. There were earlier trips— I’m thinking of the Oxford Cambridge Expedition—that gave us an incentive to do this. But they went down through the Near East and the desert, and we didn’t appreciate the desert so much. We’re both naturalists and biologists, so we wanted to go where the flora and fauna were richest, so that was across Central Africa, until we finally hit the east coast at Mombasa. Then we took a freighter from Mombasa to Bombay.

What was that experience like?

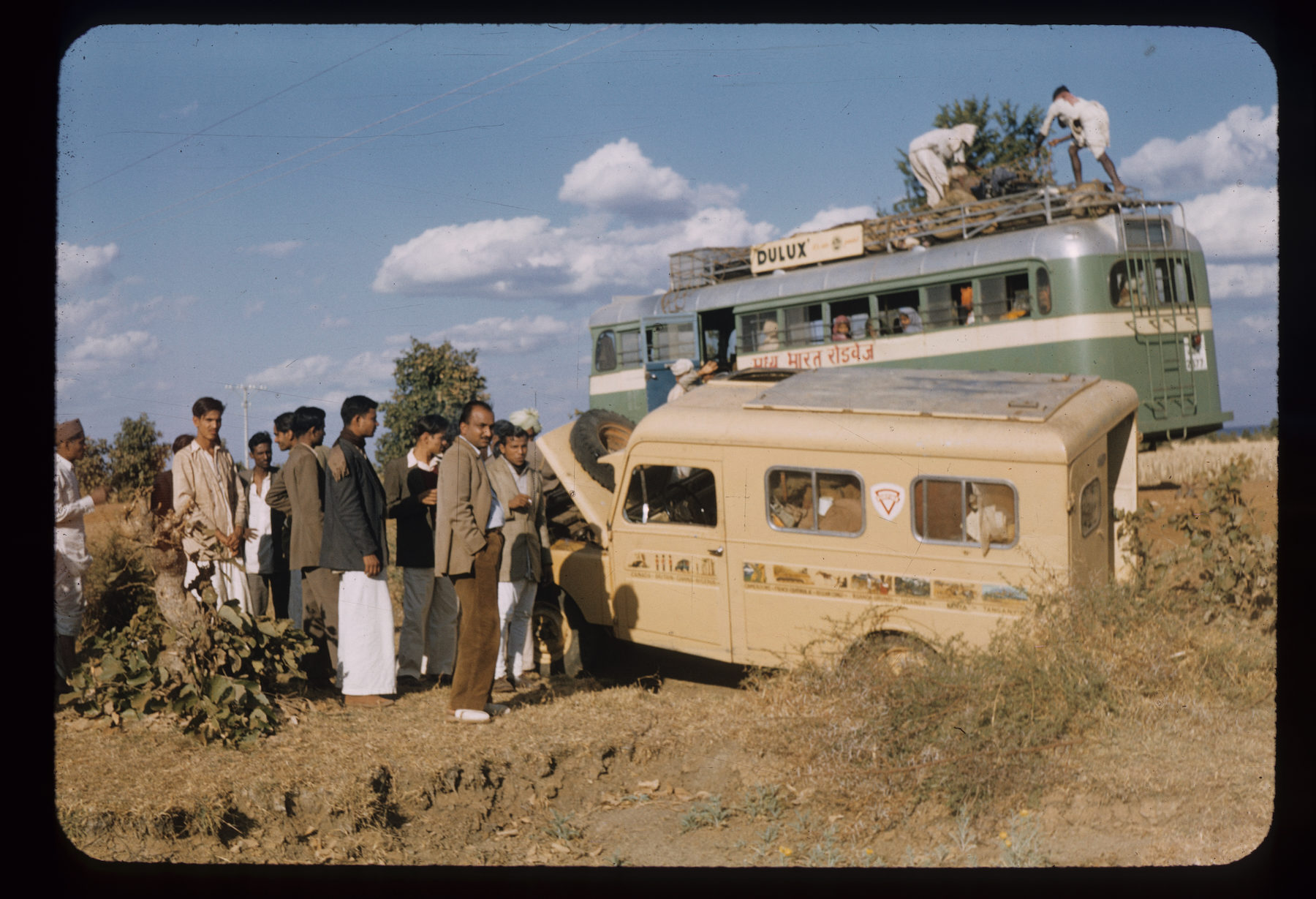

Bristol: It was very interesting. There were over 1,000 people on board. We were given a berth inside a cabin with hundreds of screaming kids and noises and the smell of puke. It’s a 10-day trip across to Bombay, so we stayed there for one night, and then we took our mattress from the Land Rover, put it up on the deck, and slept there. That was perfect because the weather was outstandingly good. We enjoyed that. We spent a lot of time with the first officer in the evening, chatting about life and love and all sorts of things. That got us across to Bombay, and we hopped out with the Land Rover and drove north to New Delhi, across to Calcutta, and so on.

Were the road conditions as difficult as you expected?

Robert: Two or three places caused us problems. One was the so-called dried-up lake in Tanganyika [Lake Magadi, part of present-day Tanzania]. It had a crust, but underneath was many feet of black, slimy gumbo. We broke through the crust and went right down. All four wheels were deep in the mud, and the bottom of the door was lying on the crust. If it had rained, that would have been it.

There was a couple in a Volkswagen Beetle who happened to be within hailing distance. They did not break through the crust, of course, because the Beetle is very light. They helped us out, and we went ashore, and we would get pieces of driftwood and drive the Beetle over to the sunken Land Rover, and we’d jack the driftwood down into the muck and then jack other pieces in the muck on top of it until finally, it took hold. Then we jacked up the Land Rover until it was flush with the ground, put stuff under the wheels, and emptied all the weight out of it.

In the Cameroons, which had the worst road of the whole trip, the Oxford Cambridge group took four days to go four miles. We did it in one day—that was all we could do because the road was so bad. The only vehicles that were doing it were Dodge Power wagons with huge wheels and a wide wheelbase. If we were going to drive in their ruts, we had to put the left two wheels in the rut and the other one up on the hump or the other way around. We went back and forth with deep mud, spinning the wheels. But we had a Capstan winch on the front with a terylene rope. You tie that to a tree and wrap it around the winch, and then you’d go off to one side and keep pulling on the rope as the winch turns slowly, and we would winch ourselves back up onto the road and get out of the deep ruts.

How did each of your strengths contribute to the trip?

Robert: I deny that I made much contribution at all except companionship [laughs]. I did art every day and kept a journal. We were writing letters for the Toronto Telegram and called ourselves the Rover Boys. We had a little Olivetti typewriter, and I could type while we were driving along.

Bristol: Well, we had similarities. Bob was the artist—and a really good artist, as it turned out, a world-famous artist. I was a mammal specialist, so I got somewhat famous with that, so we complemented one another. Almost every night, we set out mouse traps to catch specimens for the Royal Ontario Museum. We were often skinning the mammal in the morning that we had caught the night before. The Pygmies brought us a lot of small mammals to skin. I think we were paying them five or seven cents each, and we finally had to say no more because we had no refrigeration.

I also was responsible for the upkeep of the vehicle. If the brakes were failing, it was up to me to fix them, which I usually could and did. There were lots of little things going on with the vehicle, but it was riding pretty well, considering what we were driving through. That was my job, and Bob was [documenting] the trip with his paintings, his drawings, and his writing. All of that is coming out in a book, maybe one day.

You captured quite a bit of the trip on a 16-millimeter film camera.

Bristol: The film was quite tricky because we only had so much, so I was stingy with it. I wish I’d had 10 times as much film. We didn’t have the space to carry it, and there were all sorts of complications. It was great to be able to send the film home to my father in Toronto, and he would give it to processing. We didn’t see the results for a year and a half, but [the technicians] would say whether the film was fine or if we needed to adjust things.

I made an hour-and-a-half movie from the 16-millimeter film for the Audubon Society. They promoted me driving around North America as I gave hundreds of lectures on the trip around the globe. We’re doing another movie about the Rover Boys [titled The Art of Adventure] and have a very smart, bright editor, Alison Reid [director of The Woman Who Loves Giraffes, a documentary about Dr. Anne Innis Dagg, a pioneering biologist and co-author of The Giraffe: Its Biology, Behavior, and Ecology, with Bristol Foster]. She’s taking video of myself and Bob, and it’s a reflection back in time and what’s going on now in the world. Of course, it is very different than it was back then.

Were there any scary moments?

Robert: One memorable night, we were almost attacked and could have been killed. In India, we tried to hide and stop before dark so we could have some privacy. Usually, and we didn’t mind it, we had an audience, which wasn’t surprising. We were kind of unique everywhere we went. We were getting a little sick of this, so we stopped early so we could find a good clump of trees and made our supper in daylight so we didn’t have to have lights on. Then we went to bed.

We heard the shouting of angry men getting closer and closer and hoped they were just going by. But they weren’t going by. They were coming for us. They came to the back of the Land Rover, and we had two doors in the back, which were wide open with mosquito mesh. Anyway, [the men] stood around—there might have been about 10 of them—with sticks and clubs, yelling at us very angrily. The ringleader started reaching into the Land Rover under my mattress. Under the mattress, we had an air gun that looked like a real gun or rifle. It shot dumbbell-shaped slugs, and Bristol used it a bit for collecting specimens. We were quite worried he would find this gun, and then who knows what would happen.

So, [the ringleader] was yelling at me. I had no idea what he was saying. But he would say, ‘Aggabaggaboo!’ I didn’t know what to do. I was scared stiff. So I said, Aggabaggaboo! And he would go, ‘Haaaghhh!’ And I would go, Haaaghhh! His companions, the other men who were carrying clubs, saw the humor in it and started to snicker a little bit. Then they all started to laugh and chuckle and went away. That was our only close call.

What was the most surprising thing you learned about the people you encountered?

Robert: I don’t think the word surprise would be an apt description of my reaction. It was more like eating a wonderful turkey dinner—savoring, enjoying, and soaking up. Certainly, one of the highlights was to spend five days with the Pygmies in the Ituri Forest in the Belgian Congo.

We had heard about a woman by the name of Mrs. Putnam, who was from the Bronx and had quite a fascinating story. [In 1946,] she was walking along the beach on Long Island in the offseason, in the middle of winter. There was a guy walking too, at a distance, and they couldn’t ignore each other, so they had to at least say hello. They started to chat a little bit, and I guess he said, ‘What do you do?’ She said, ‘Well, I’m an artist. What do you do?’ He said, ‘I actually keep a kind of hotel for Pygmies in the Belgian Congo.’ [Editor’s note: the man was field anthropologist Patrick Putnam]. We had heard about her, so we drove up to her house and chatted away. But our time with the Pygmies was one of the most moving experiences of the entire journey.

How so?

Robert: To start, the setting of the Putnam house featured the biggest thatched building I’ve ever been in. It was a huge circle with mud walls and this high conical roof, which, to my memory, was maybe 30 feet high or so, which meant you were looking at the underside of the thatch with the ceiling going up and disappearing into the gloom. In the center of the room was a high hearth, about 3 feet tall, that you could pull your chair up to. It was quite a magical evening listening to the stories of the Bambuti and Mrs. Putnam, with the glow of embers on people’s faces as we sat around the fire.

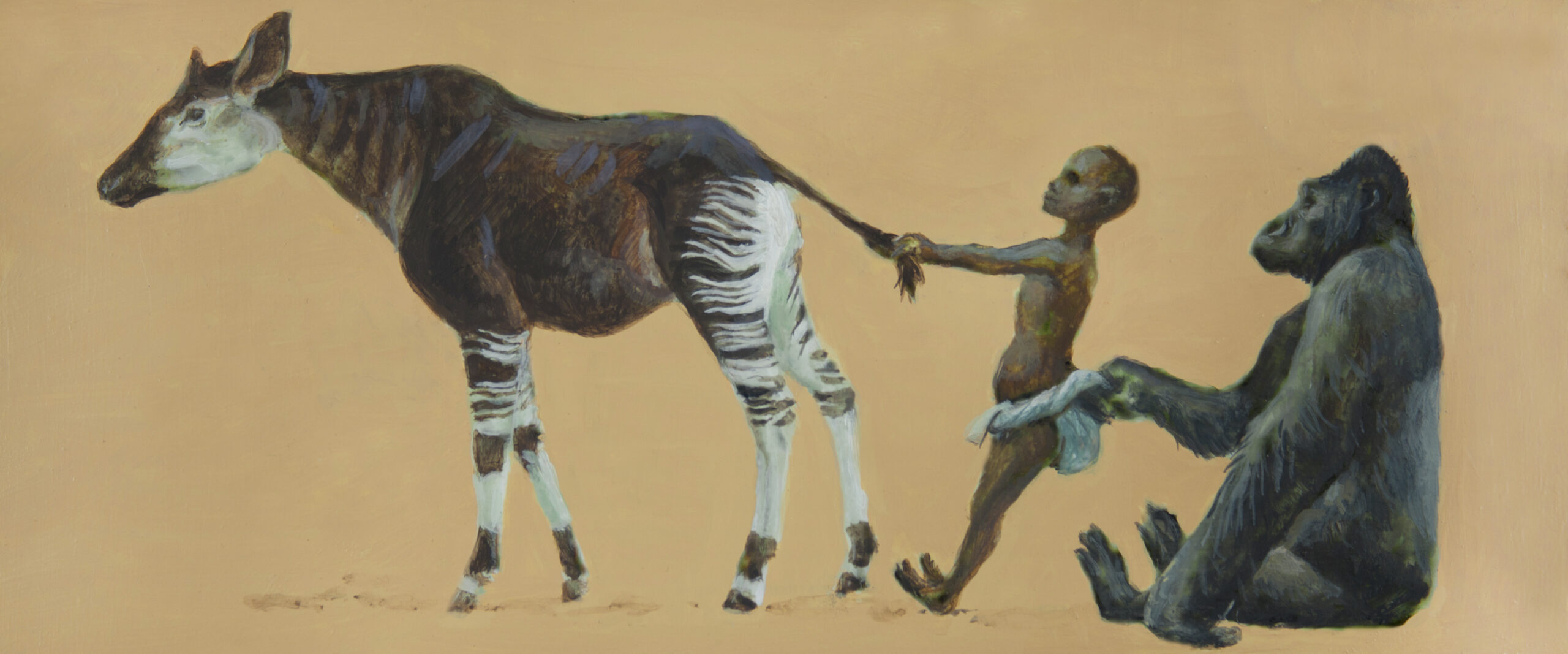

The next day, we joined the hunt. I guess we had about 20 people sitting on the roof and the hood of the Land Rover, and we drove where they directed us. They arranged for the women to go ahead on foot. The men had homemade nets about 20 or 25 feet long made out of twisted fiber, and they hooked them on twigs and bushes. The next man hooked his to the next man’s net and strung this out through the forest. The virgin tropical rainforest had immense trees with great buttress roots and was quite open below because of the canopy. There are whole ecosystems, including birds, mammals, and reptiles, that never set foot on the ground, easily going for miles without running out of canopy.

Then we started to hear this wonderful yodeling, singing, kind of calling in the forest by the women, [who were] getting closer and closer. They were clapping their hands and trying to frighten forest creatures and the duiker, a small forest antelope. One [duiker] on that particular sweep came running and got tangled in the net. The next thing I’m going to say is a little hard to hear, but in the whole group, there was only one knife, and the guy near the animal didn’t happen to have the knife, so they broke all of its legs. The guy with the knife arrived a few minutes later, and they cut its throat and butchered it on the spot. It was a male duiker, and of course, it had large testicles, and the teenage girls wanted those. As soon as they received the testicles, big smiles on their faces, they got quite excited and ran off, I believe, to roast them.

What did you learn about the Bambuti people that you didn’t know before you arrived?

Robert: Well, I knew very little about them at all before I got there. Of course, Bambuti are very small, less than 5 feet tall, and came up to my Adam’s apple in height. What I concluded was that they are among the most perfect people, fitting best with nature. They consider the forest their mother and father and all of their ancestors. They understood every aspect of it in the kind of detail we would never comprehend. The way a twig is bent, or four or five blades of grass are flattened means something. They would know what had passed by and how long ago. They could read it all. And music was a big part of their life—songs of praise and thanksgiving. None of them were lamentations but cheerful songs.

Does overland travel lend well to the naturalist?

Robert: I don’t want to torpedo the thought because my life has almost been based on it. But a famous environmentalist—his name is escaping my mind at the moment—said, ‘I have a solution to problems of the environment in the world. Two words: Don’t move. Don’t get in cars and drive. Don’t get in airplanes and fly. Stay where you are and get a full life right where you are.’ I think that’s probably true.

I’ve probably said this already—I’m a hypocrite and moved quite a bit. I’m conscious that moving isn’t good for the planet. I’m doing a lot less of it, partly for reasons of principle and scruples and partly because I’m an old guy. But I’ve done a huge amount of moving, including the greatest one of all, which was this trip with Bristol.

What are your favorite books?

Bristol: Ernest Thompson Seton. A good one for children is Pogo Possum [by Walt Kelly], which has some good environmental messages.

Robert: I like all of Gerald Durrell’s [books]. My Family and Other Animals was one of his most famous. Another one is by Laurens van der Post, A Story Like the Wind, about the San people who live in South Africa. Out of Africa by Karen Blixen. West with the Night by Beryl Markham—it’s a wonderful read about a pioneering woman who spent time in Africa.

Bristol and Robert in Ngorongoro, Tanzania, in 2012. Photo by Birgit Bateman

*

The Legacy of Grizzly Torque, the 1957 Series I Land Rover

Decades later, the legacy of Bateman and Foster’s Series I Land Rover extends well beyond the Canadians’ 1957 and 1958 round-the-world adventures. At the tail end of their trip, Foster stayed in Sydney, Australia, to teach wildlife ecology. Several months later, he and Grizzly Torque boarded a ship bound for Vancouver, Canada, where Bristol sold the vehicle to a biology student studying peccaries, a type of wild pig, in Texas. Eventually, the Rover disappeared for several decades under the guise of a coat of blue paint.

In 2006, collector and enthusiast Stuart Longair purchased four dilapidated Series I Land Rovers from a farmer’s barn near Williams Lake, British Columbia. It turned out one of them was Grizzly Torque. However, Longair didn’t know this then, so the vehicle sat for another 10 years before stumbling across a photograph from Foster and Bateman’s expedition on a Land Rover website. Curious, he contacted the Rover Boys to confirm. The driver’s door window gave it away as it was outfitted with plexiglass—a result of damage incurred in India after Foster served to avoid a bicyclist.

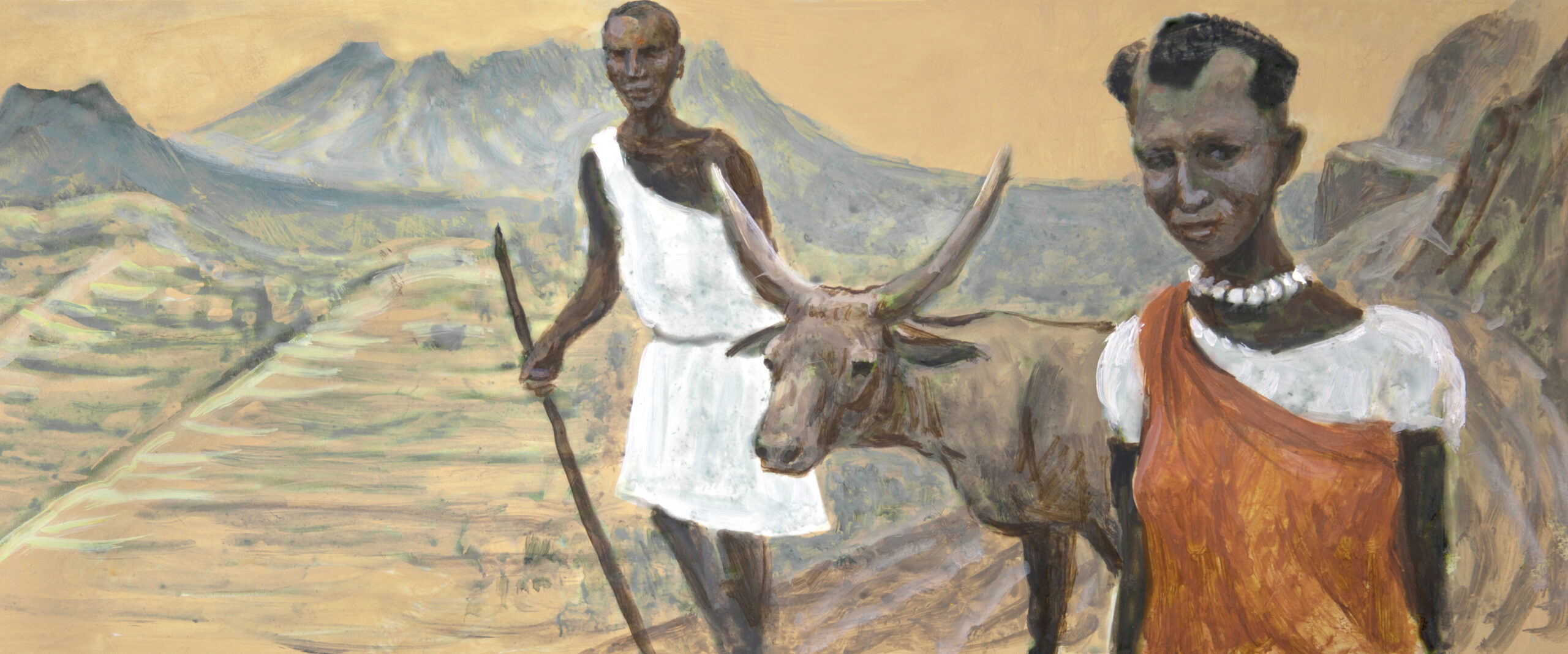

Stuart commissioned a complete vehicle restoration including, according to Silodrome, “bodywork … made of the same Birmabright alloy that was used for Aston Martin sports cars.” Robert Bateman repainted his original vignettes along the side of the Rover—his tributes to each country they traveled through. Grizzly Torque, in all its splendor, became the star of Land Rover’s 70th Anniversary celebrations across Canada and has appeared at various events. It seems 67-year-old “GT” has embarked on another adventure, as the vehicle was sold for $123,200 USD as part of an RM Sotheby’s auction in Monterey on August 19, 2023.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in Overland Journal’s Winter 2024 Issue.

Read more: The 1958 Women’s Overland Himalayan Expedition

Our No Compromise Clause: We do not accept advertorial content or allow advertising to influence our coverage, and our contributors are guaranteed editorial independence. Overland International may earn a small commission from affiliate links included in this article. We appreciate your support.