There was a mix-up at the border crossing. There, I said it. To this day I still can’t recall what we were actually thinking or exactly how it happened. Rule number one in overlanding… always ensure your paperwork is in order. We skipped past about 100 trucks queued up on the embankment road and followed the GPS directly to the Mali customs building. It was busy but we managed to get the carnet stamped out of Mali. We asked about our passports and we were waved on. We found a gap in the road and carried on driving. After we crossed the river, we found what looked to be the Senegal side of customs, so we queued up and got our passports sorted. We asked about the carnet and they waved us onward again so on we drove. About two miles down the road, we realised that we must have missed it, or taken a wrong turn etc. So we turned back to the passport stamping place and they directed us to the local police station, where we woke a man who was not impressed to see us. He looked at our passport and carnet, did some stamping and signalled us to go on. Now, I’m not sure what exactly happened here (or even previously!) but somehow we managed to leave without the Carnet getting stamped. Maybe in the chaos of getting our passports stamped, we forgot about the vehicle. This all happened over a few hours in the morning, fighting the parked up trucks, queues, street hawkers, unhelpful customs staff, bureaucracy, rubber stamps and ramshackle buildings that showed no indication of whether they were customs, police, the local bakery or someone’s residence. Whatever happened our passports were not stamped out of Mali and the vehicle was not stamped into Senegal! We drove on, heading northwest in a poorly vehicle, tired and unsure what to do about the Carnet. We pulled off the main road to wildcamp that night and relaxed in the glow of the setting sun.

We arrived at the Zebrabar near St. Louis the following afternoon and met Martin and his wife. They have lived there for quite some time and have set up an overlanders haven on the Senegalese coastline. Martin has his own workshop for vehicles and employs locals to work in the kitchen to supply campers or guests with some tasty meals or snacks (they have a number of small accommodation blocks). We sheepishly told them about our Carnet… They couldn’t believe it and explained in detail what would happen if we got caught – fines and/or deportation. They advised us to head to the main customs/police in St. Louis to try and get it sorted there. They called ahead for us, as they knew them very well.

As it turned out, things were going to get worse. We were pulled over by an angry little policeman, so we indicated and turned onto the verge. He asked us to pull over some more, further into the verge, which we did. Calmly he asked for Simon’s IDP (International Driving Permit) then tried to bribe/fine us because we didn’t indicate the second time when pulling further onto the verge. Nothing we said made a difference, so I told Simon to give him the $5 because if he asked for more paperwork we would be in big trouble.

We hadjust paid our first bribe in four weeks. Remarkably, we didn’t get stopped again and made it all the way into St. Louis. We found Customs and they were very helpful but didn’t fully understand how this had happened, or why we drove nearly 1000 miles directly across the country to where we were all now sitting (we couldn’t explain that either). Eventually we received a piece of paper covering us until we could get help at Customs at Diema, just on the border. We drove back to the Zebrabar and got stopped another three times just trying to get out of St. Louis, so we were thankful for the note!

We left Zebrabar the next day for Diama to see if they would stamp our paperwork. It was less than 100 miles to the north but seemed to take a long time in a limping Land cruiser. After an hour of Pidgin English conversation overlooking the Mauritanian desert, we managed to ‘blame’ the customs guys on the Senegalese side for not stamping our carnet. He looked at us out of the corner of his eye, almost not believing us but as we had this ‘piece of paper’, he issued us a three day ‘passavant’ to cover us until we reached Dakar where we could get our Carnet in order (at a cost). With a sigh of relief, we returned to Zebrabar with the good news, only getting stopped six times through St Louis… We spent the rest of the day looking at the fuel tank leaks and taking the front propshaft off as the UJ was destroyed. How we had gotten this far, I will never know.

We headed for Dakar the following morning in the darkness that is 5am, taking the main routes south with difflock engaged. With worries of winding up the transmission we took every opportunity to disengage, coast along and re- engage which usually happened at the numerous speed bumps entering and exiting every village and town along the route. Entering Dakar, we managed to hit rush hour and had to battle our way through to the port. We stopped at a number of locations, trying to get someone to understand what we were trying to do, but just got passed around. Some just didn’t have the ‘right’ rubber stamp. Eventually a young chap said he knew where to go and hopped in the back of the Toyota; he was on the phone for most of the time and giving us directions. Turns out he was picking up what we think was his dad, who dived into the Toyota among our bags, photography gear, laptops and satellite broadband unit. The older gentleman was shouting and gesturing with a general African tone of aggression. We told him to calm down or get out but he didn’t seem to understand. Either way, he found the man we needed to speak to and got us in there to see him pretty sharpish. He spoke on our behalf and we have no idea what was said but the right rubber stamp emerged from the top right drawer of the desk and in slow motion began to stamp the triplicate page for the temporary import of our vehicle into Senegal. A wave of relief and $40 to the aggressive man who wanted $200, and it was on to challenge number two… Propshaft UJ.

It was lunchtime in Dakar and we decided to stop and eat first before heading to the main dealer. I’m giving this a mention here because it was perhaps the best roadside food we had eaten in all of West Africa. It was a little café next to the port, run by a lone Senegalese woman with only 5-6 tables inside. The food was exceptional and came in what I would describe as a ‘western portion’, meaning it was enough to fill you. Some places we had visited we had to order our meal twice to the disbelief of the staff, as it just wasn’t enough and we are not exactly big guys! Suitably filled with sustenance and a glimmer of hope, we set off for the Toyota main dealer. They were closed for lunch or whatever from 11am to 2pm, giving us a brief window of two hours before they closed at 4pm. It took two hours and seven ‘windows’ to get the UJ and persuade them to press it into the propshaft for us. They wouldn’t refit it, however, as it was 3.45pm and they wanted to close. So we refitted it ourselves in their car park, much to the annoyance of the gun-touting security guard telling us to leave while we swore at him from under the vehicle. Finally fitted, we were done, so next we had to find a camp site outside Dakar. Two lanes turn into six at rush hour in Dakar, and everything grinds to a halt. It took three hours to drive the 20 or 30 miles out of Dakar to the main road by which time it was dark and it had been an extremely long day with only a little rest. Worn down by this, we decided our best hope was to head back to Zebrabar so that is what we did, driving through the night so we could relax the next day. Arriving at midnight we quietly opened the main gate and drove in, parking back up exactly where we left earlier that day before putting up the tents and crashing out. It was our longest day having driven for some 14 hours and covering over 600 miles, with much of the time spent arguing with officials!

We still had two national parks to map while we were in the north. The parks in Senegal are generally bird sanctuaries; migrating birds from all over the world depend on the wetlands that make up most of the protected areas. We would have to map these parks in a different way because driving was not an option. Instead, we took boats, pirogues and other local vessels and used the hand-held GPS to map our routes, waypoints and important features. Leaving the truck behind and letting the guides take us in various directions was a welcome break from sitting behind the wheel.

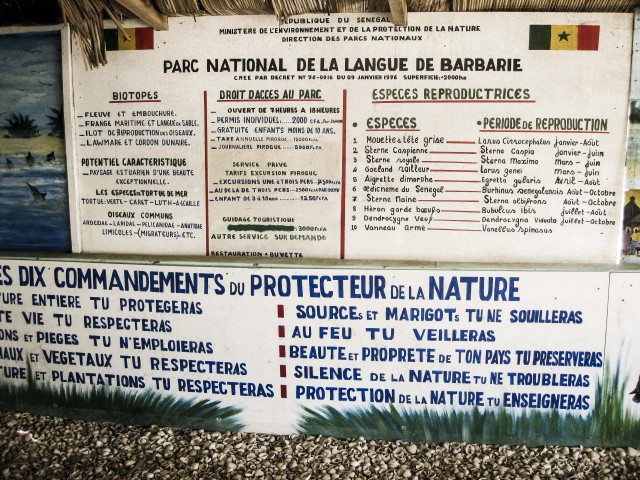

The first park we visited was The Langue de Barbarie. It is right by Zebrabar and is easy to get a local boat trip (pirogue) with a guide right from the shoreline. Our guide was an enthusiastic young chap who grew up in the area. We saw plenty of bird life over the next 45 minutes that included terns, pelicans and a distant osprey. The Langue is a thin sandy peninsula that shields the mainland from the Atlantic Ocean and provides a haven for migrating sea birds.

The second park that needed mapping was Djoudj National Bird Sanctuary, so the next day we headed off in that direction. To get there we had to drive back through St. Louis and got stopped no less than six times! Within 50km of our turn-off, there was a clunk and a scrape… We pulled over to inspect the latest failure. The main fuel tank had sheered its cradle brackets and the nose of the tank, which was nearly full, had ploughed a line in the gravel road. The tank seemed OK but the bracket was toast. With some ingenuity using a ratchet strap, we managed to secure the tank well enough to get back to Zebrabar. On the way through St Louis we had the cradle welded up and picked up the bolts and bits we needed to fix it. After being stopped another four times, we made it back to camp and spent the remainder of the day under the truck.

While at Zebrabar, we got to know some of the other guests including a group of ladies from the US. They didn’t have their own transport so we offered them the three seats in the back of the Land Cruiser and the chance to come and visit the Djoudj Bird Sanctuary with us (and to also see exactly what we were doing). The added advantage of this was having a female presence, as the police no longer seemed interested in holding us up for any length of time. They also spoke better French than both of us combined.

Djoudj National Bird Sanctuary is situated in the Senegal River delta near the Mauritanian border and is a wetland of 16,000 ha.

The park was chiefly established as it is an important region for birds, being one of the first fresh water sources they reach after crossing 200km of the Sahara. From September to April, an estimated 3 million migrants pass through, including shoveler, ruff, pintail and black-tailed godwit. Thousands of flamingo nest here regularly as well as white pelican, white-faced tree duck, spur-winged goose, several species of heron, various egrets, spoonbill, and Sudan bustard. Mammals including the warthog and West African manatee, and several species of crocodile and gazelle have been successfully reintroduced into the area.

But this wildlife haven is threatened from many sides. Agricultural chemicals seep into the waters of the Senegal River, disturbing delicate links in the food chain, and a dam is being built which will disturb the annual wet-dry cycles that have brought life to Djoudj. A study sponsored by the World Heritage Committee has reported on the measures required to ameliorate the effects of the dam through an inexpensive series of dikes and sluice-gates and a carefully timed release of the life-bringing waters. It is hoped that the World Heritage status of Djoudj will help convince the government of Senegal to take the necessary measures and that tourism will take notice from the work of the MAPA Project.

We arrived at the park and booked ourselves on the next boat trip out along the backwaters. Armed with the GPS and our cameras we boarded a wide and open boat as we headed off away from land for the next couple of hours, marking waypoints as we went. The backwaters were lined with tall grass that concealed crocodiles and Nile monitor lizards, and we spotted a variety of birds including a majestic fishing eagle. With the watercourse recorded on the GPS, we disembarked from the boat and drove around the main lake, following every possible route. We found a number of hides tucked away in trees overlooking predominantly dry lakes. One large lake had dramatically decreased in size, and we could just make out the pink flamingos in the distance. We followed bumpy tracks and trails for most of the afternoon and then called it a day, heading back to Zebrabar, now referred to as ‘base camp’.

After processing the day’s data and sending it to March in South Africa, we rewarded ourselves with a few beers before bed. The plan was pretty straightforward from this point on, as the project had more or less come to an end. By this time, Seb and Chris from Team 2 had made their way through Sierra Leone, Liberia and Guinea and would map the parks in the Gambia on their way through to Dakar. That left one more small reserve south of Dakar on the coast at Popenguine. It was agreed that we would head down there and map the park, then rendezvous with Team 2 in Dakar in the next few days.

Popenguine is a small coastal village populated by ex-pat ‘artists’ which has a small nature reserve just to the south of the village, adjacent to the coast. This is the first and only park in Senegal managed by the National Park Service in partnership with the local women’s group, RFPPN (Popenguine Women’s Gathering for the Protection of Nature). It is only possible to hike through the 2493-acre park, as there are no routes for vehicles. Landmarks include the Cap de Naz, the lagoon for bird observation and a number of concrete WWII bunkers/gun emplacements. We spent the afternoon walking and logging our route, climbing to the top of the cliffs and scrambling around the gun emplacements before heading back to the truck. We spent that night in a local campsite that had a great pool and was right on the beach, a welcome treat after a hot and dusty few weeks.

The last few remaining days of the trip were spent in Dakar clearing out the truck, backing up MAPA data from both laptops and the GPS systems, arranging for the kit and trucks to be returned to South Africa. We managed a bit of ‘tourist’ sightseeing, and spent some time with Seb, Chris and their friend Dale in his apartment complex in Dakar. We ate well, from tuna steaks on the Braai to eating out in some great coastal restaurants. With Seb finalising the container shipment for the trucks back to Durban, there was nothing left to do but hop in a taxi and head to the airport. Our once in a lifetime mapping project had sadly come to an end.

Epilogue

Five weeks in West Africa felt like a very long time, even when we were two weeks in. The mapping part of our expedition went very well and was, for me at least, enjoyable. Probably the most critical aspect of the expedition was the ill health of the truck in general. The vehicle had been driven by previous volunteers all the way from South Africa up the west coast route through Angola, DRC, Congo, Cameroon, Nigeria, Togo, Benin etc. and hadn’t been well serviced due to the limited facilities in these countries. It had been driven hard for nearly a year prior to it landing in our hands. Everyday we had to nurse it along in one way or another and the fuel leaks never went away. It was a constant worry, day in, day out.

An expedition with a purpose, the mapping of these National Parks allowed us, pushed us even, to go further and deeper into blank spaces on the map. If this were a regular overland journey, we would probably have turned around long before we got to where we did. Driven by the need to map these parks, we passed through some truly remote villages, saw some exceptional landscapes and stayed in places that truly epitomized the term ‘wild camp’.

Without the MAPA Project and Tracks 4 Africa, we would never have had this opportunity and for that I (and I am sure I speak for Simon too) am truly grateful. My advice? If you see an opportunity for something that you want to do, go for it. It doesn’t matter if the details are unknown or the dates ‘don’t fit’. Lodge your enthusiasm.

On a final note, my Grandad passed away a week prior to our departure, and I felt terrible leaving my family behind. At the time of his funeral (which Lisa attended for me), we were mapping Deux Bales NP in Burkina Faso. We stopped driving so I could take a moment to honour his passing. With that moment, the expedition became a tribute to him, and I will always associate this trip and my love of Africa with him.