It’s not that I don’t have friends, quite the contrary. I tend to travel alone because after several decades of analyzing it, I have deduced that I simply enjoy my own company. I think quiet and solitude are the perfect antidotes to the chaos of a busy life. My aloneness within big landscapes also amplifies my headspace, the refuge where I really go to escape and get lost.

There really is safety in numbers. It provides redundancy of gear, more decision making brainpower, built-in human resources, and much more.

I mostly relish the challenge of going solo, but understand how venturing out with no one else to rely on can multiply the dangers. That too appeals to me for reasons I can’t explain. It’s not unnecessary risk taking if I do my due diligence and plan accordingly. Because I’m intrinsically studious, I spent years researching the best lone wolf explorers in history, from globe circling sailors to the most celebrated mountaineers, naturalists, and even astronauts. There’s a surprising amount of nuanced skill required to be an adventuresome party of one.

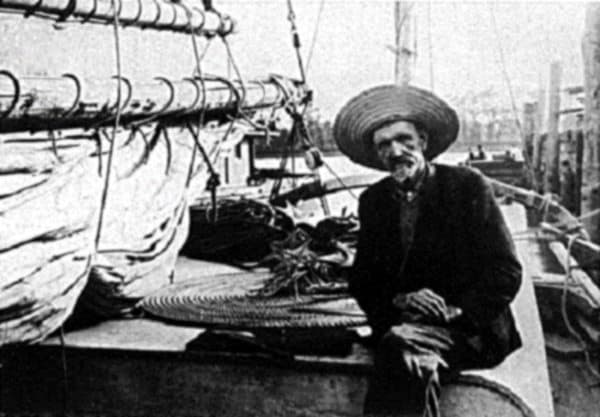

Master Lone Wolf: Joshua Slocum

In 1900 Joshua Slocum published a best selling book chronicling his solo circumnavigation of the globe aboard his sailboat, the Spray. The first American to make the journey, he covered more than 46,000 miles and visited virtually every corner of the planet. His book speaks to the challenges of solitary travel for extended periods of time and proves that time alone is never lonely.

Why go solo

Not to dismiss any of the more introspective reasons to leave your travel mates behind, there are a few reasons why it can be preferred. Traveling solo allows me to move at my own pace. Whether on a motorcycle, bicycle, skis, or on foot, everyone has a tempo they not only find most comfortable, but safe. Nobody likes to be rushed anymore than they like waiting around for a sluggish partner. There are also settings were a lone traveler is faster. Speed can be essential for survival. The ability to quickly get over a mountain pass to avoid a storm, or cover big miles before supplies run out, factors into one’s risk assessments.

With no partner or group of people to manage, the soloist has more individual flexibility. I can wake up late, go to bed early, even leave my camp in the middle of the night without lobbying for approval, or coaxing people to get moving. I can press hard, go slow, stop for lunch when I want––it’s my call. Some of my travel pals are also notorious for bad ideas. I generate enough on my own and don’t need additional help. Peer pressure is dangerous. It can lead you to do things you wouldn’t otherwise do.

Another element I like is the fact I’m responsible for only me. As an adventure guide for over a decade, I’ve spent countless days coddling clients. With just myself to attend to, those pressures are eliminated and I can enjoy the experience for what it is and not how it’s being impacted by others. The other obvious reason I go it alone is because the older I get, the more difficult it is to get my calendar to coincide with my friend’s schedules. I can go when time permits.

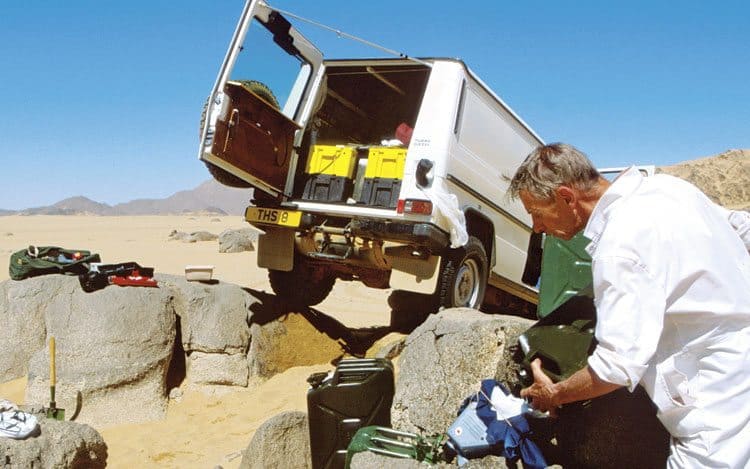

This is the kind on nonsense I get myself into when I’m with others. If solo, I never would have tackled this road. It’s tempting to let others lure me out of my comfort zone, even if they’re not actively trying to do so. I ended up in a pile of regret a second after this shot was taken.

I spent years plying the fjords of Alaska as a solo kayaker on multi-day journeys. Decisions were made cautiously, mistakes carefully evaluated as to not be repeated again, but it was exceptionally rewarding.

How to go it alone safely

There’s no substitute for intensive planning. The best tool I have for survival is the mass of grey goo between my ears. I plan for success and I plan for mishaps. I plan and redraft my plans until I can plan no more.

When I have finally sorted out the details of a trip, I share them with at least one other person. This is basic stuff we all have been told before. Tell someone where you’re going. More importantly, tell them not just when you’ll be back, but when you’ll be back if things go a little wonky. Establish specific times when you want to be considered late, late to a point of concern, and so late it’s necessary to dispatch the cavalry. Give yourself time to be tardy, but know precisely when you told your home support team to send help. If things get ugly, you will need to remember that information without ambiguity.

In the event you are long overdue and your situation proves dire, search and rescue teams will want to know just how prepared you are for your predicament. Leaving behind a list of items you have with you will establish your odds of survival and maybe play into their rescue strategy. They’ll amp up their efforts, maybe putting themselves at risk, if they think all you have is a hoodie and a Snickers.

Master Lone Wolf: Reinhold Messner

Arguably the most celebrated mountaineer of all time, Reinhold Messner made a name for himself as a soloist in 1978 by climbing Nanga Parbat and in doing so became the first man to ascend all 14 8,000 meter peaks. In his 60 books he has written, he often talks about climbing solo, accompanied only by the spirit of his brother Günther who died on that same peak in 1970. He has famously said, “I’m never alone when I solo.”

The soloist’s mindset

When I travel alone, it’s a radical departure of mindset from trips with friends. Everything is a potential risk. While on a mountaineering trip in Alaska, my climbing partner was pouring hot tea inside our tent and not only dumped boiling water on his left hand, he drenched his lower leg. A simple careless mistake made it impossible for him to comfortably wear a glove or a plastic mountaineering boot. Had he been alone, he would have been hosed. When I’m solo and doing little things like pouring boiling water or using a pocket knife, I count to three, gather my focus, and contemplate the fallout if I screw up.

The single biggest challenge for the soloist is the process of making critical decisions without any extra brains around to help. Hard choices have to be carefully calculated and discipline exercised to stick to that choice. Vacillating with yourself will only make you nuts and erode your confidence. Once you deprive yourself of confidence, the bad decisions begin to come in droves. Most people who die in the wilderness didn’t make one bad decision, but a series of them. The key is to avoid the first bad decision.

Master Lone Wolf: Tom Sheppard

This man needs little introduction to the overland audience. One of the most well traveled gentlemen of our generation, his iconic G-Wagen has plied the shifting sands of the Sahara for decades, most of those miles logged without fellow companions. Methodical and academic about his planning, he is probably better suited to lone travel than he is in a group.

Backups and the sucker’s bet

Going anywhere solo is already a gamble, the last thing you want to do is introduce more uncertain variables than necessary. I carry a GPS, but also a map and compass. I always pack a satellite communication device like a Delorme inReach, but I never count on it to work, and inform my contacts at home that it may not work. I also assume that good weather forecasts will prove wrong, the storm of a century is on route, and anything that can go wrong––will.

The inReach is my favorite tool for lonely wandering, but I always assume it won’t work and tell my friends and family the same.

Other tips

Don’t dress like a tree. This is a big one I see violated way too often. Overlanders love earthy tones, but when you’re huddled under a tree clinging to life while rescue helicopters circle overhead, your choice to dress like a bush will haunt you. I enter the backcountry looking like a box of crayons. Not because I like it, it’s just the smart thing to do.

Never take unproven gear. This falls under the Sucker’s Bet header. Don’t wait until you are miles from help to test out that new pair of boots, stove, tent, or water filter. Mitigate the risks of failure whenever you can.

Reduce the difficulty. I’m more inclined to travel a tough road via motorcycle with partners than I am alone. Ratchet back the difficulty of the trip when you go solo to enhance your chances of a pleasant trip.

As a lone driver in a single vehicle, I often avoid situations were a complicated recovery might be an issue. I spend more time traveling and less time extracting myself from a bad situation.

Take notes. I carry a small notepad and pencil on every outing. It’s too easy to forget the mental notes you make to yourself when in the field. There’s also nobody else there to help you remember.

Don’t skimp on gear. Traveling in a group has the benefit of inherent redundancy. The soloist has a minimum of kit, so everything has to be top quality and very reliable. Is saving $100 on a tent a smart choice? Spend the money. Buy the peace of mind.

Failed gear is worse than gear you forgot to bring in the first place. Make bad gear choices––suffer bad gear consequences.

Practice. Even if you travel in a group, practice the soloist’s mindset when you can. Think about how you would make key decisions, or observe how group-think differs from that of the lone traveler.

It’s extremely rewarding to plan an adventure for one and execute it perfectly. You get to take credit for the success, develop your self reliance and self confidence, and it will make you a better group traveler in the end. If you have yet to try it––do.