Photography by Akela World

Conditioned from childhood to view the desert as a place where rain doesn’t fall, things don’t grow, and life can’t thrive, we can be surprised by what we encounter when we go. Camped off a remote trail system in the region outside Phoenix, Arizona, just before the first day of spring, my husband and I found ourselves stymied by a peculiar sound. Too inexperienced to grant anything but a human cause, we guessed a 4WD outing had gone mechanically sideways. The scratchy, jarring sound continued on and off for hours. Imagine our surprise when the nonchalant culprit wandered from the brush—the local burro.

Desert, defined as having less precipitation than evaporation each year, occupies a full third of land on Earth. There are several types, ranging from frozen tracts like Antarctica and the Arctic to the largest hot desert, the Sahara in North Africa, which is nearly as large as the continental United States. For its part, the US holds four major deserts, all in the western part of the country–Great Basin, Chihuahuan, Sonoran, and Mojave, as well as smaller desert regions.

Those of us fortunate enough to experience these areas for ourselves know there is nothing like the stillness of the desert, restoring our souls from the frantic pace we often choose. Our sense of wonder is ignited when we discover life there again and again. Native plants and animals are endlessly fascinating and have adapted to the harsh environment in a myriad of ways. Southwestern cacti like the saguaro or Mexican giant cardon have been known to live for 300 years, and they are an ecosystem bastion that provides food and shelter for surrounding species. Across the Atlantic, a current favorite of mine is the desert lion, reestablished along Namibia’s Skeleton Coast in 2002 after a decades-long absence. These impressive animals live in the dunes but head to the beaches for the majority of their food intake, including fur seals and marine birds.

Because of its apparent barrenness, concern for desert land may not come so intuitively. Nonetheless, these regions stand in need of the conservation travelers can offer. Here are positive steps you can take to treat the desert with care when you visit.

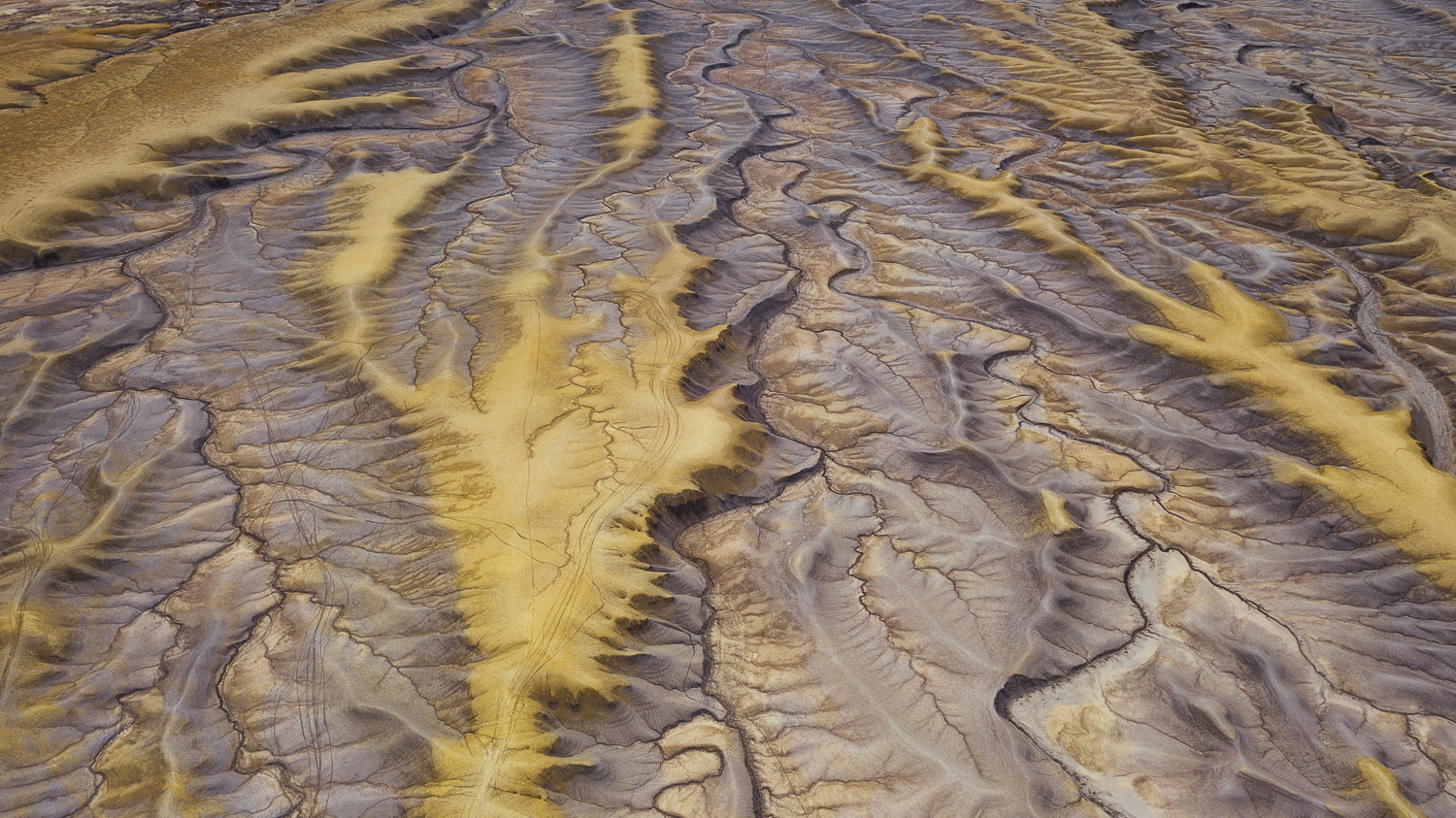

Respect Posted Signs Desert ecology is complicated, and posted notices are meant to protect the fragility and interconnectedness of desert life. For example, pet rules should be closely followed. Our furry companions can inadvertently damage native fauna or even transmit disease. Where trails and tracks are clearly defined, it may not seem necessary to stay within boundaries. What we may not notice is the desert’s delicate skin, a black crust called cryptobiotic soil. This deceptive desert feature is teeming with microbial life. It absorbs water, allowing groundwater recharge and sustaining plant life while reducing soil erosion. When damaged by footprints or tires, cryptobiotic soil takes years or even decades to recover. These are just two justifications for the posted signs we sometimes disregard.

Where Rules Are Nebulous or Nonexistent, Choose the Right Thing In many regions of the world, no one is monitoring our conduct. Even where conservation-based rules exist, they are not always enforced. During times when no one is watching or nobody cares, we get to choose how we are going to act. We can respect the land as we would in our home country or disregard what we know. The latter is surprisingly easy to justify. I had been anticipating Peru’s Paracas National Reserve largely because of images I kept seeing from other travelers on Instagram. In these stunning photos, overland vehicles were perched on the edge of sand-covered cliffs with the dark Pacific surging below. As we drove along gravel through the national reserve, posted signs instructed drivers to stay on the designated road. Yet we kept seeing tire tracks leading off the road (including those from local fishermen) across the sand to the cliffside. With a sinking feeling, I realized two things. First, I wouldn’t be able to get the photos I wanted without breaking the rules. And, second, many overlanders before us had disregarded the signs, knowing there would be no penalty. It’s worth considering whether we need legal consequences to behave a certain way or whether we will choose self-governance that respects our surroundings, no matter where we are.

Know Weather and Soil Conditions Regrettably, I’ve learned this one the hard way. It was early April, and we hadn’t camped in the Moab area so early in the year before. We claimed one of our favorite BLM (Bureau of Land Management) spots, an isolated site requiring four-wheel drive and high clearance to access. The weather was ideal when we arrived, but we neglected to check the forecast. Overnight, heavy rains fell, and we awoke to a thin sheet of ice on our tent. Navigating out was both dangerous and difficult. We lost traction on a steep slope because our tires were caked in mud, and ended up sliding off the trail at the bottom, stuck. By the time we self-recovered, the trail was a horrendous mess. We’d never made this mistake before, and it was painful to see what we’d done to the track that had been so firm one day before. If we had familiarized ourselves with seasonal weather patterns and consulted the forecast, we could’ve chosen our campsite more wisely.

Pack It Out or Bury It Properly Where humans meet desert waste is a recurring issue. Whenever possible—and it usually is for vehicle-based travelers—human waste should be packed out. When absolutely necessary and legally permitted, waste should be buried 6 to 8 inches at least 200 feet from running water. Twelve inches deep is better in areas where coyotes and kit foxes live due to their curiosity and sense of smell. Pack out used toilet paper. When we fail to dispose of human waste properly, animals can dig up shallow catholes and attract insects. Food waste should also be managed appropriately. When food is left at campsites or thrown in fires, vermin can feed and multiply. On some public lands, this has led to growing concerns about the spread of hantavirus.

Mind Your Ammunition Recreational target shooting is permitted on most BLM land in the United States. In these areas, participants should consider green ammunition, also known as green bullets or green ammo, to prevent significant quantities of lead buildup in concentrated areas. Many best practices associated with recreational shooting on public land are outlined and readily accessible at blm.gov.

Author and environmental activist Edward Abbey wrote, “The desert is a vast world, an oceanic world, as deep in its way and complex and various as the sea.” As we cut our engines and still our minds, the desert will compel our respect. In response to the desert’s great gifts, we should leave as little evidence of our presence as possible. In this, we allow its undisturbed stillness to touch others seeking its restoration.

Get Involved

As vehicle-based recreation continues in popularity, trail systems in specific regions require regular maintenance. Areas like Moab, Utah, and Sedona, Arizona, along with many others, need volunteers to collect and haul away trash, repair and mark trails, close off user-created unauthorized trails, close illegal campsites and eliminate their fire rings, and other tasks that protect the larger desert ecosystem. There is typically a government employee at the relevant BLM or national forest unit who can communicate volunteer needs (for example, see fs.usda.gov/managing-land/trails/priority-areas/sedona for Coconino National Forest around Sedona). Overlanding communities, off-road clubs, and other groups can coordinate with the public land agency in their area to organize events that move the dial where it’s most needed. If you’d prefer to join an existing event, search the internet for “[place name] trail clean up,” with the place name being your nearest BLM land, national forest, or another desert ecosystem in your area.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in Overland Journal’s Winter 2024 Issue.

Our No Compromise Clause: We do not accept advertorial content or allow advertising to influence our coverage, and our contributors are guaranteed editorial independence. Overland International may earn a small commission from affiliate links included in this article. We appreciate your support.