The silence of the Alvord Desert is all-consuming. The column of quiet that descends on the dry lakebed in the evenings reaches through you. Sounds that would be swallowed by the regular cacophony of a workaday wilderness are amplified, like they’ve been plugged into a Marshall stack—the rumble of a pickup truck on the county road a dozen miles away, the thud of a grasshopper landing heavily on the cracked mud at your foot, the creak of the frame of your camp chair as you lean back to take in the stout expanse of Steens Mountain to the west.

There is unease in the tranquility. Ghosts haunt the playa, gliding over its preternaturally plumb surface as sure as the landsailers leaning into the morning gales. It was here that “the fastest woman on four wheels,” Jessi Combs, crashed and died in 2019 while setting the women’s land speed record in her North American Eagle jet-powered racer. It’s difficult to imagine the fury and clangor a jet engine would inflict on the Alvord’s hush. The playa is open ground, and you’re welcome to drive in all directions and at any speed across its 84-square-mile expanse.

But travel lightly and carefully. The lakebed hides certain dangers like difficult-to-suss wet spots riven with sucking mud and large stones, the likes of which might have upended the North American Eagle on its last ride. The faster you go, the more the horizon seems paradoxically to run away from you in the glimmer of a mirage. Despite the temptation of 450 horsepower at my beck and call in the 2018 Ford F-150 Raptor I was driving, with a measure of respect for the landscape and for Jessi Coombs, I took it easy exploring the playa. Fools rush in where angels fear to tread.

There are few places left for the fools among us to really get lost, but Oregon’s Alvord Desert country is one of them.

General Information

An unlikely landscape in one of America’s most remote and least populated corners, the Alvord Desert is where the northern reaches of the Great Basin run headlong into the Pacific Northwest’s volcanic corridor. The overlapping rain shadows cast by the Coast Range, Cascades, and Steens Mountain conspire to limit rainfall in this region to as little as 5 inches every year. However, as true denizens of the desert know, aridity does not necessarily equal emptiness.

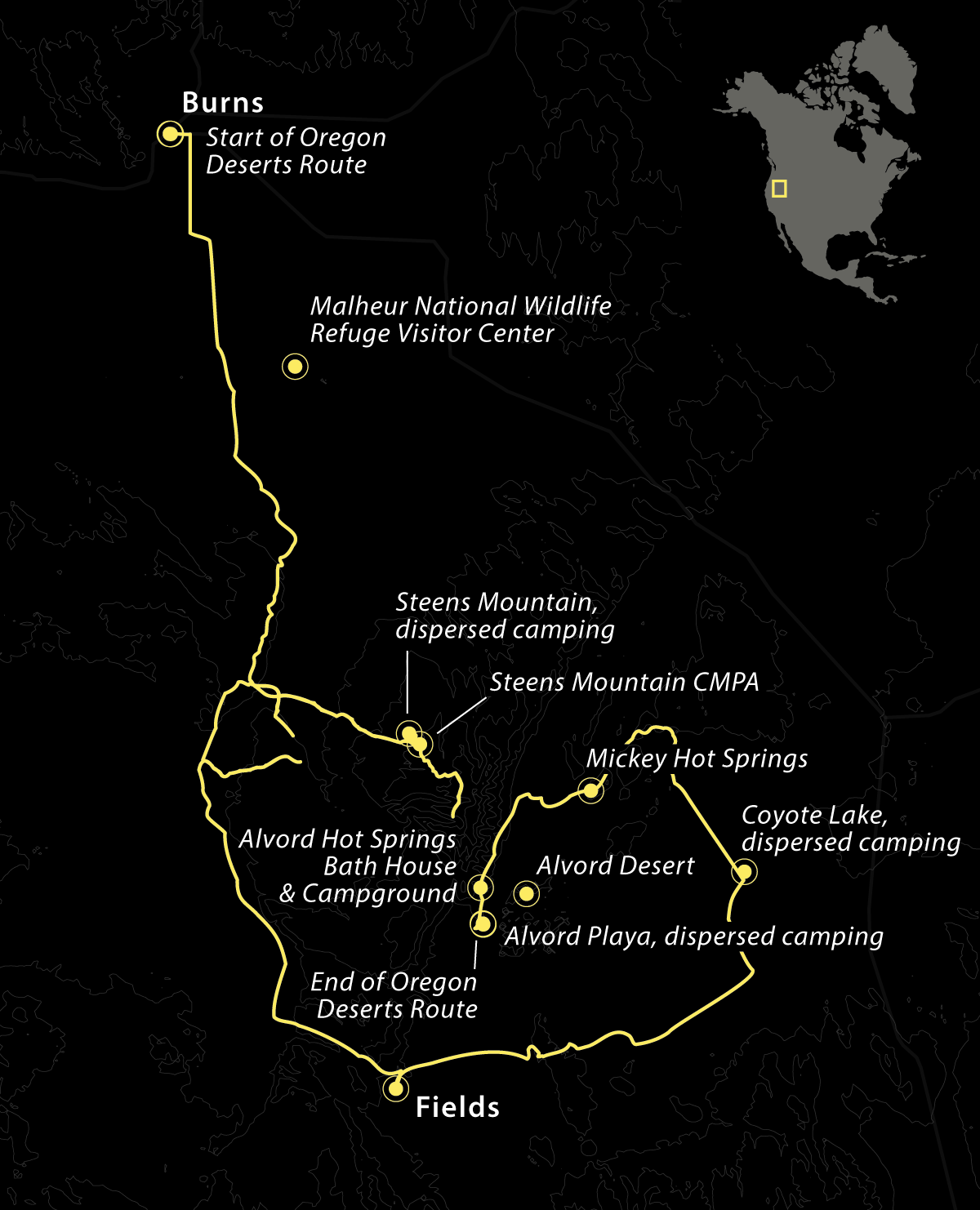

The route detailed below is one variation on a theme—the miles of tracks interlaced across the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) lands that dominate this part of the Beaver State make for lots of opportunities to forge your path. However, the patchwork of publicly owned land and private property can be confusing, especially since much of the BLM territory is leased for grazing. There are lots of gates to open and close. Visitors need to pay careful attention to these boundaries so the roads stay open to future voyagers. Some landowners allow transit through their properties but not camping. Trespassing is taken seriously, and the private lands layer on my onX Offroad offline navigation app kept me from breaking the law.

Finally, preparation is key. Except for Burns and barely-there Fields, Oregon, there is no civilization within 50 miles of this route and very little in the way of cell signal, basic services, or even water. Pack more supplies than you think you may need and prepare to be self-sufficient in every aspect of your travels. Be ready to backtrack if your chosen route peters out, as most roads here are not regularly maintained, and they may simply disappear into the sage without a trace. Resign yourself to being dry and dusty—the fine silt that covers the off-road tracks and dry lakes will make its way into everything you own.

The Route

In July 2023, Central Oregon was suffering from the double blow of record-high temperatures and a plague of meaty Mormon Crickets. By the time I turned the wheel south from the insect-slicked US Route 20 at a fuel stop in Burns, Oregon (with 2,700 souls, it’s by far the largest town you’ll encounter on this route), I was more than ready to escape both the swelter and the sickening crunch of countless exoskeletons under my BFGs.

Oregon Route 205 leads you deep into the heart of Harney County, the state’s largest and least densely populated. The highway’s grand, sweeping curves provide long views of the high desert as you climb out of the washes and up the sides of one sage-studded mesa after another. I rushed past the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge, a haven for both migratory birds and birders, on my way to the Steens Mountain Cooperative Management and Protection Area (CMPA).

Over 75 percent of Harney County is federal land, and Steens Mountain looms at the center of it all—a 9,738-foot remnant of a long-dormant shield volcano, roughly 50 miles long on its north-south axis. A significant portion of it is managed as true roadless wilderness, but broad swaths of the peak are crisscrossed with many miles of engaging off-piste tracks.

Basque immigrants settled in Oregon over the span of nearly a century, and you will encounter their legacy across Steens Mountain, both in the sheep herds that still meander the meadows and in the aspen groves where they established their shepherd’s outposts. Above the treeline, I found snowfields as the highest road in the state reaches practically all the way to the peak. The eastern face of the mountain falls away precipitously to the Alvord Desert, almost 5,000 vertical feet below, and the view you take in will leave you as breathless as the elevation.

Elk, bighorn sheep, and mule deer roam the slopes of Steens among the willow thickets and several endemic species of wildflowers. I rambled along the many spur trails that fan out from the main road corridor, seeking out shy wild horses, and ran across one small group with yearlings who promptly took their leave, trotting off among the juniper and spooking a couple of sage grouse. Rejoining the highway, I made my way with a grumble in my stomach to the hamlet of Fields, Oregon.

Fields is the last stop on the way to anywhere. The Fields Station offers the desert traveler the only opportunity to fill up on fuel, groceries, and a meal for many miles in any direction. Prices and selection reflect this fact (brace yourself for $9 per gallon for premium unleaded), but the Fields Station has its charms. It’s clearly the hub of the tight-knit local community, and I enjoyed a substantial breakfast platter on the outdoor patio and chatted at length with the manager, a disabled veteran and a Raptor enthusiast.

Climbing back into the Ford, I set my sights on a desert trek and a wild camp in the parched reaches to the east and north of Fields. I picked my way across the jumble of grazing leases and along power-line and ranch access roads. Alternating between deep sand and sharp volcanic stones, these routes constantly changed as I scrambled over steep escarpments and down into dry lakebeds. I disgorged myself from the truck many times to open and close the gates that keep the local cattle herds in their place. I paid a visit to a pair of 6-foot-high cairns built atop a prominent ridge looking south toward Nevada and stared deep into the hot pools of the only active geyser area in Oregon at Mickey Hot Springs.

These recently discovered pools are not the only thermal activity in the area, as many smaller hot springs bubble up in isolated canyons and washes—the legacy of Oregon’s ancient geologic past. Be wary of these wilderness springs as many are too hot for humans or contain unsafe levels of toxic elements, not to mention they harbor delicate microecosystems that are easily damaged. Stop instead at the Alvord Hot Springs Bath House and Campground, which offers day-soaking in their pools and a few well-tended campsites. I opted for an isolated wild camp on dry Coyote Lake, not far from the Alvord Desert but well away from the many cows lowing their way among the rocky outcrops.

After two days of demanding off-road driving, I reached the Alvord Playa with a plan to spend the final day of the journey out of the truck and simply sitting on the edge of the desert in the silence. I followed a sliver of shade as I read or just stared into the shimmering waves of heat radiating from the crazed expanse of dry mud. As the sun finally dipped below the bulk of Steens Mountain, I found myself planning new adventures in the Alvord. There’s so much more to see here for fools like us.

Access

Steens Mountain Entrance The primary access to the Steens Mountain Loop is located near the Page Springs Recreation Site (42°48’33.6″N 118°52’05.4″W), just 3.5 miles from the hamlet of Frenchglen (42°49’43.2″N 118°54’56.5″W), which straddles County Road 205 West of Steens Mountain.

Alvord Desert Entrance The Alvord Desert encompasses a huge landscape, but I joined the spiderweb of tracks and trails that spread across the region just north Fields, Oregon (42°15’51.2″N 118°40’28.6″W) at the junction of County Road 201 and a prominent powerline road (42°17’22.4″N 118°39’54.4″W). From there, the adventure is up to you.

Logistics

Total Miles: 305 miles

Suggested time: 3-5 days, depending on your patience with desert environments

Longest distance without fuel: 75 miles

Fuel Sources

Burns, Oregon: 43° 35′ 13.239″, -119° 3′ 15.789″

Fields, Oregon: 42° 15′ 51.7422″, -118° 40′ 30.1794″

Frenchglen, Oregon (check for availability): 42° 49′ 37.4484″, -118° 54′ 53.4234″

Difficulty (3.0 out of 5.0)

The main Steens Mountain loop can be navigated in an AWD vehicle with standard ground clearance, but the shifting conditions and quality of spur roads on Steens Mountain and the tracks in the desert portions of the route demand 4WD. Few advanced off-road obstacles exist, but the potential for unexpected severe erosion, washouts, and other road damage can quickly ramp up the difficulty factor. Wet roads may prove to be impassable.

When to Go

I traveled this route in the height of summer during a record heatwave, but the relatively high elevation, especially on Steens Mountain, meant nights were pleasantly cool. Late spring can bring thunderstorms that turn the pervasive silt into dangerously sticky mud, making some roads inaccessible. Autumn will see the turning of the aspen trees in the mountains and the fall elk rut, along with considerable numbers of hunters, so solitude may be at a premium. Winter closes the Steens Mountain loop road and many of the more remote tracks in the desert.

Permits and Fees

Only certain BLM campsites (such as the Page Springs Recreation Site or the Jackman Park Campground, for example) have use fees; the rest of the route traverses dispersed public lands where you are welcome to camp for free. Remember to minimize your impacts at wild camps.

Suggested Campsites

Steens Mountain, dispersed camping | 42° 45′ 18.4356″, -118° 38′ 28.6902″

Coyote Lake, dispersed camping | 42° 33′ 58.1718″, -118° 5′ 26.8764″

Alvord Playa, dispersed camping | 42° 29′ 34.4898″, -118° 31′ 42.9594″

Alvord Hot Springs Bath House and Campground, Call for rates, reservations recommended | 42° 32′ 37.7664″, -118° 31′ 59.484″

Contacts

Alvord Hot Springs Bath House and Campground alvordhotsprings.com, 541-589-2282

Bureau of Land Management, Burns District Office blm.gov/office/burns-district-office, 541-573-4400

Malheur National Wildlife Refuge fws.gov/refuge/malheur, 541-493-2612

The Fields Station General Store thefieldsstation.com, 541-495-2275

Resources

I carried the DeLorme Atlas and Gazetteer: Oregon, as well as the onX Offroad app (onxmaps.com) on my iPhone, which works offline if you download the route and map segments you intend to travel ahead of time. Inquire about local road conditions and closures at the Burns District Office of the BLM and The Fields Station. Local knowledge is often the best knowledge.

It is recommended that the traveler utilize redundant GPS devices (like a phone and a dedicated GPS), along with paper maps and a compass. This track, along with all other Overland Routes, can be downloaded on our website at overlandjournal.com/overland-routes/.

23 Overland Route descriptions are intended to be an overview of the trail rather than turn-by-turn instructions. We suggest you download an offline navigation app and our GPSX track, as well as source detailed paper maps as an analog backup. As with any remote travel, circumstances can change dramatically. Drivers should check road conditions with local authorities before attempting the route and be ready to turn back should extreme conditions occur.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in Overland Journal’s Summer 2024 Issue.

Please enjoy Overland Journal Podcast Episode #194: Global Adventures and Overland Journalism with Steve Edwards

Our No Compromise Clause: We do not accept advertorial content or allow advertising to influence our coverage, and our contributors are guaranteed editorial independence. Overland International may earn a small commission from affiliate links included in this article. We appreciate your support.