Golden rays of light skipped over the red sands of the Simpson Desert, dispersing long shadows in their wake and alerting us of a new day. Peering out of my swag and across a shallow ephemeral lake, small birds pecked at the newly formed tarn. Breaking camp on this morning would begin the second half of ARB’s Outback Experience. In Part I of the adventure, I’d signed off after trekking the backroads from Broken Hill to the edge of the Mundi Mundi and delving into the Sturt Stony and Simpson Deserts. After getting washed out of Eyre Creek we returned to Birdsville.

Two days earlier it had been nearly void of life. But on this afternoon, utes and horse trailers lined the town’s riding arena. We’d happened upon the Birdsville Rodeo (pronounced row-day-oh for us non Aussies). In a world where you and your neighbors may be separated by a 10,000-acre cattle station, the church, the pub, and the rodeo become a cohesive bond for community and kind. In the stands, true-blue locals munched on meat pies (traditional Aussie snack), and cheered while friends and family members wrestled unwitting calves to the ground.

The Outback is a land with deep roots in cattle and sheep ranching. In the days before mechanized transportation, stock was moved the old fashion way, on foot. It was an undertaking was of great scale and proportion, and the annual trek became known as The Great Australian Cattle Drive. But it came with risks unknown to city dwellers like us, and it was the history of these intrepid pioneers that us drew us to the Birdsville Track.

Other than the 500-plus kilometers separating the two points, Birdsville to the north and the train depot in Marree to the south, the terrain is relatively void of geological deviations and lacks topographical or physical barriers. It is also lacks water. We were in the center of Australia’s cattle country and over a thousand kilometers separated us from the nearest seaport. Such was the dilemma for the early cattle ranchers—how to drove cattle through one of the most arid and inhospitable environments on the planet…and get them through alive.

In the mid 18th century there weren’t any reliable sources of water along the route. Cattle drovers like Jack Clark and the S. Kidman Company would depart Birdsville with up to 2,000 head of cattle bound for the transportation depot at Marree. Clark and Kidman’s route would become the footprint for Birdsville Track, the primary economic arterie to the outside world. Getting to Marree was a four-week endeavor, to which fate would often play a key role. In Clark’s case, a fierce sandstorm pinned his drovers down for days, scattering the stock and reduced its number to only 72 by the time he reached Marree. It was such an undertaking, and with so dire a consequence if things went awry, that between 1880 and 1920 the Australian government funded the digging of a series of bores (wells). What they found was the Great Artisan Basin, a 1,000-foot deep artesian aquifer that spread across most of the region.

A few hours from Birdsville, we crossed a non-descript two-track to the west. Our wagon master, Michael McCulkin of Tri-State Safaris, knew it was the road to the Page family grave. A single white cross marks the spot where the Page’s car broke down in 1963. Stranded without water or food, and a hundred kilometers from town, the family of five, three children and their parents, headed out on foot. The 100-plus degree heat drove them back to their car where they perished on Christmas day. They were found 11 days later, so badly decomposed that the townsfolk dug a hole with a tractor and pushed the car in, bodies and all. It was a chilling reminder of how harsh and unforgiving this land can be.

To our good fortune, the rain gods had been smiling on the Outback, releasing it from a 10-year drought and allowing the blue lines on our map (creeks) to live up to their names. Midday we realized we’d broken a sway bar bracket on the Toyota Tundra. After temporarily securing it, our resident mechanic, Mark Lowry, would later MacGyver a replacement bracket from used bubblegum and bailing wire.

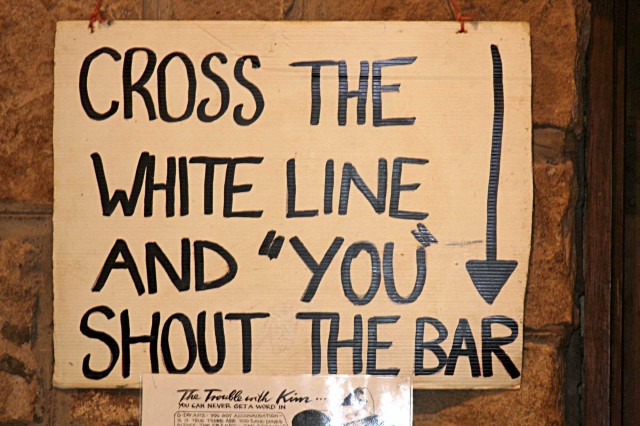

The clouds gave way to sunshine as we slogged south towards the Mungerannie Roadhouse. Sitting on the banks of the Derwent River, one of the few semi-perennial water sources in the area, Mungerannie was established in 1886 as a supply depot for shepherds, stationers, and travelers. The sinking of a bore by the government in 1888, from which entrepreneur William Crombie sold water to cattle drovers, secured its future. That same bore now provides warm water for a riverside hot tub. After setting up camp along the water, we soaked in the warm spring and tossed back stubbies until the sun was well below the horizon.

Though the last official cattle drive on the Birdsville Track was in 1972, the drive has recently been reborn as an annual event and drawing would-be drovers from around the globe. Somewhere before reaching Marree we met Shannon Bell, a 6th generation drover and rancher. Shannon’s ancestors planted roots on the edge of the Tirari Desert in 1893 and were droving hands in the early cattle drives. Shannon and her brothers are the real deal, and continue the family’s work and tradition. We said our goodbyes and they continued with their 400-kilometer trek, The Great Australian Cattle Drive, to Marree.

Known as Hergott Springs until World War I, Marree was once a center of commerce in the Outback. After the Central Australian Railway reaching town in 1884, it became the main conduit to Adelaide and Port Augusta. It was also a staging depot for the Afghan Cameleers who supplied remote Channel-country cattle stations with supplies. An occasional dog naps in the middle of the road these days, and the original rail station lies in a state of slow decay. We visited a small open-air museum which houses several railcars, period relics, and a small mosque, erected in honor of the Afghan Cameleers of the Outback.

The Prairie Hotel came into view about mid-day. If you ever thought about scooping up fresh road kill and serving it up for dinner, the Prairie Hotel’s feral food specials have got you covered. Smoked roo (kangaroo), camel pie, and emu stew—we dined on the feral food sampler…delicious!

Turning east towards the Flinders Range, temperatures began to cool, clouds were forming above, and we were leaving the arid Outback behind. Passing Leigh Creek we peeled off the main road and up a canyon lined with native cyprus and red river gum. As we gained elevation the increase in vegetation also meant an increase in wildlife. Elusive during our desert trek, emu and kangaroos grazed on ample supplies of grass before bounding into the brush as we approached. This night we do a farm stay at one of the Flinders oldest sheep stations, the Wirrealpa.

The Flinders, which date back 640 million years, is Australia’s largest mountain range. Sedimentary and volcanic layers containing some of the first known multi-cell life forms (from the Ediacara period) were folded, faulted, and pushed high above the surrounding plains. During the last half-billion years, wind and water have eroded and washed away softer layers, leaving the region ripe for agriculture when the first Europeans arrived in the 1850’s. Prior to that, the indigenous Adnyamathanha people, who were made up of the Kuyani, Wailpi, Yadliaura and Pangkala, resided in the Flinders for tens of thousands of years.

Warren and Barbara Fargher greeted us as we pulled into the Wirrealpa at dusk. The sun cast a warm glow across an array of 1860 circa stone and mortar buildings, one of which we would call home for the next two days. Warren’s father acquired the Wirrealpa in 1957 and the family has run sheep and cattle in traditional fashion for the past five decades. Cattle and sheep stations in this part of the world are larger than one can imagine. Between the Farghers and their cousin Walt, whom they share a 20-mile common fence, they manage a 1,000 square miles of land. That is 640,000 acres. When asked how they get around, Warren said “Yamaha dirt bikes, four-wheel drives, and a Cessna make it much easier to keep an eye on things.”

The following morning, a light rain began to fall as we headed out for a day on the trail. With a station of this size, we could run new routes all day and never leave private land. Visiting the decaying ruins of long-abandon drovers huts, hand-dug wells, and even a section of sand dunes brought us to the top of Carry Peak. The dry and thirsty soil embraced each drop that was released from increasingly gray skies. Rain followed us through the afternoon; subsiding by the time we pull through the gates of Wirrealpa and heard the dinner bell ring from the mess hall. They say, “When in Rome, do as the Romans.” Aussies lover their beer, so we joined in for a few tinnies and enjoyed an evening of cowboy poetry from famous Aussie Outback Bob—something about Grandma’s bosoms getting caught in a clothes wringer.

Well before dawn, the timely crow of a rooster resonated through the shearer’s quarters like a natural alarm clock. In the darkness, the aroma of coffee on a light breeze let our minds drift back to a time before jumbo jets and automobiles, to a time when the world seemed like a simpler place and priorities were less cluttered. The sound of footsteps on a creaky wood plank floor reminded us that we had an early rendezvous this morning.

The sun broke through the clouds as Warren’s Cessna 182 banked left over a jagged rift on the eastern Flinders and a full view of Lake Frome came into view; the Strzelecki Desert beyond. We had come almost full circle since our departure from Broken Hill. Reflecting back, we’d traversed Strzelecki Track, stood on the corner of three states at Cameron Corner, dodged kangaroos, emus, and deadly snakes, and followed dusty hoof prints of early drovers on the Great Australian Cattle Drive. As with all good things, ARB’s Outback Experience was coming to an end. However, in this vast and timeless land where tradition, culture, and the natural world coexist, the friendships developed and memories shaped will last a lifetime.