Meet Karin-Marijke, Coen and their Toyota Land Cruiser BJ45, on the road in Asia and South America since 2003. They are often characterized as the slowest overlanders in the world but for them it’s all about staying in places and connecting with people. The following is just one of many informative and entertaining posts from their beautiful website: landcruisingadventure.com

“The most important decision you’ll ever make is whether you live in a friendly universe or a hostile universe” ~Einstein

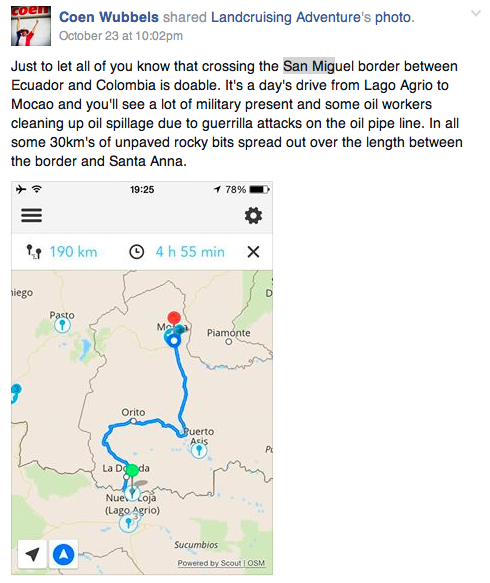

After we had crossed the border of San Miguel between the Ecuador and Colombia, Coen posted the following on the PanAmerican Travelers Facebook group:

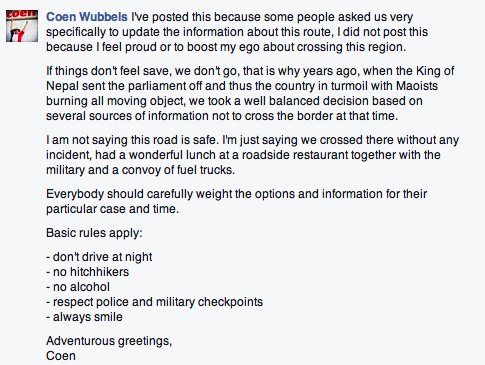

We got a mixed response with some members called us careless. Coen commented and added this:

While for some that added a (much wanted) nuance to the initial post, others continued to call us careless.

Being Careless vs. Making an Informed Choice

I found it an interesting thread. In our opinion, we weighed the pros and cons and took a decision based on reliable information on both sides of the border (read about the actual border crossing here). We don’t feel we did something reckless at all. How could others see it so differently? Coen and I discussed the topic at great length.

When is something doable? When is something safe? When is something reckless? Often safety issues are clear and there is no discussion about them. For example, today Chile or Argentina are safe travel destinations whereas most of us will agree that visiting Syria isn’t a good idea right now. Today, countries such as Iran, Pakistan and Colombia spark the debate: go or no go?

In some cases safe/doable/reckless balance on a fine line. The interpretation of a region being safe or not may differ. This is not the first time we’ve come across contradictory opinions. Let me give you an example:

Traversing the Baluchistan Desert in Pakistan or not?

The main road through the Baluchistan Desert, from the Iranian border to Queta in Pakistan, runs along the border with Afghanistan. The region is known for smuggling and banditry. In east Iran we traveled with a Dutch couple. They were afraid to drive in Pakistan and had considered shipping around it. They asked if we could team up for this stretch as they felt safer driving with two cars, which was fine with us.

Coen and I had another idea. After Quetta we wanted to cross the Baluchistan Desert once more, but then all the way down to the Arabian Sea. After his conquests on the subcontinent, Alexander the Great lost his army here when returning to Europe and it hasn’t been a much traveled region ever since. To know whether it would be a safe stretch from Quetta to Gwadar, we did a couple of things, among which writing to the Dutch consul in Karachi.

He wrote back. The first part of his email was a copy of the embassy’s official statement which warned us against traveling in Pakistan no matter where. We discarded it as this opinion came from officials who never left the capital of Islamabad and had little or no clue of what was happening outside of that city.

But, very kindly, the consul had added his personal opinion about this particular area. Coen printed two copies and handed one of them to our friends. That night we read the letter and highlighted all the parts we liked, which confirmed our wish to drive to Gwadar. We concluded this would be doable. The next morning over breakfast our friends didn’t look that happy, stating, “Were not going. It’s too dangerous.” They had highlighted exactly the opposite of what we had underlined, searching for the confirmation of how dangerous it was.

Our truth was no higher than theirs, or visa versa. It does show how we can interpret information differently.

I guess you can say that the example also shows our search for the positive, for signs of optimism, for confirmations that something is possible (doable, if you like). We search for ways to make something work. We see the positive in people and situations. This, of course, doesn’t mean we are always right. I use the example to show how we stand in life, our journey. Others may have a different outlook on life, and, of course, that’s fine too.

Where Do We Draw the Line?

We love adventure, we love stretching our boundaries. We entered Bhutan illegally as we did Tibet.

Having said that, we don’t care for endangering our lives. When we traveled in India, we heard how ‘everybody’ went to Nepal. However, by the time we wanted to go to Nepal, the Nepalese king had seized power, the Maoists were at the height of their struggle. While it was safe to fly to Kathmandu, the Maoists were patrolling the roads, setting cars on fire or confiscating them. We skipped Nepal and moved on to Bangladesh instead.

Contrary Opinions – Who Do You Believe?

It is tricky, isn’t it? Because it all comes down to whom you believe. Do you go for the story told by person A or by person B? You may choose A while the other traveler opts for B.

For example, when we were in Mocoa, in south Colombia, we hopped in the back of a local pick-up truck to go from our camping spot to “El Fin del Mundo”. This is a hike in a beautiful, remote, mountainous area to a 70-meter-high waterfall. One of our fellow passengers said we shouldn’t go there by ourselves. “Very dangerous”. “If you go, only go in a group, and with Colombians,” she added.

Her opinion stood in complete contrast to the (foreign) owner of our hostel Casa del Rio, who has run this place for four years. There have been no problems hiking this trail at all, he said. Furthermore, during the days we’d been there other travelers had hiked the trail, all foreigners going solo or in duos. They had not encountered problems.

So there you have it. Contrary opinions. Who do you believe? It is without doubt that all were sincere in their opinion and based it on their experiences or stories they had been told.

How Do You Determine the Safety of a Region?

As is clear from the examples above, there isn’t one answer to the question how to decide whether a region is safe. It depends on your outlook on life, your past experiences, your character, and the persons you talk to.

Here are options we have used to make informed choices (in random order):

01. Other overlanders

We listen to travelers who recently visited the city / region / country. We value experiences of overlanders over those of backpackers because we share more similar experiences (border crossings with paperwork for the car, road conditions, check points, etc).

02. Journalists

In the case of Nepal we took the advice of two Dutch journalist who we knew personally. They had just returned from Nepal and discouraged us from going.

03. Embassy / Consulate

03. Embassy / Consulate

You can always search for information on embassy websites. Truth be said, this is something we have never done. In the case of Pakistan we got their advice through an email but ignored it (Note that there is much more to this story as to why we dismissed their opinion but this is not the place to elaborate on that).

It was interesting to see, in this particular case, how the opinion of the consul stood in contrast to that of officials in a capital 1500 kilometers away. As the consul had actually lived in the region for years, we valued his opinion.

04. Police Officers and Soldiers

Both can be a reliable source of information. When soldiers at the San Miguel border (Colombia) told us it was safe to drive to Mocoa, we believed them. They have lived and worked here, know the risks, and they have no interest in travelers getting hurt.

In most areas in Pakistan there was no doubt about where we were allowed to drive or not. If a region was unsafe, soldiers closed it off and sent you back (mind you, this was ten years ago and says nothing about the current situation).

05. Local Authorities

In India it was clear: we needed permits for some of the Northeastern states and we weren’t going to get them at that time because the situation was considered unsafe. Period. End of research.

For the Baluchistan Desert, on the other hand, it wasn’t clear at all whether we needed permits. Some officials said we needed one to cross the southern part of the Baluchistan Desert, others said we didn’t. Our default interpretation being a positive one, we read that as we didn’t. Others may chose the opposite and either fight for that permit or give up.

06. Locals

We find that the trickiest one. As you may have experienced yourself, when you go from one country to the next, locals are often aghast. Turkish people were shocked to hear we were driving to Iran while the Iranians didn’t understand how we had survived Turkey.

In South America local people are filled with horror when you tell them you are going to Brazil. Heck, talk to Brazilians and many of them will warn you not to visit the big cities in their own country, never mind that they have never been there themselves. The argument to “listen to ten locals and if they all say the same it should be good,” doesn’t work exactly for that reason. Ten locals in ten remote villages in Brazil may all tell you not to go to Río de Janeiro or São Paulo, which is an opinion based on fear mongering and not a reliable advice.

07. Other

07. Other

Of course we have Internet, newspapers, guidebooks and maps that can all help in gathering information about a region.

Obsolete vs. Up-to-date information

Whatever the advice, it has to be up-to-date information. This is why I dislike blogs without dates. It makes their information totally unreliable.

When people email us for practical information about Pakistan or Iran (“Is it safe to travel there?”), we answer that we can’t help them. Our journey to those countries was ten years ago and situations have changed.

Trust Your Gut Feeling

Most of all we trust our gut feeling. There is our inner voice that warns us for danger. Coen and I have come to completely trust that voice. The times we haven’t listened (generally because we were tired, fed up, angry, in a bad mood), we got in trouble. Fortunately, most of the time our voices say the same thing. One time that didn’t happen was when driving down the Vía Auca, in Ecuador and we were confronted by indigenous people (read about it here).

Even if we all listen to this voice and the same advice, your gut feeling may say something different from mine. Our gut feeling is not a rational thing. That feeling, we believe, is based on experience, on how we stand in life, on how you we with people and tricky situations. E.g. I know for myself that when I encounter a threatening situation, rationality takes over. I don’t panic, I don’t get scared. Rational thinking is my default reaction in times of danger. It’s Coen’s as well.

When fear, or anger, or feeling uncertain, is your default response, your gut feelings will respond differently. One default system isn’t better than the other. They are different, and there are many more than the ones I mention here. Having said that, it is good to know what your default response is, because it help you understand your gut feeling to a situation.

So, I guess that pretty much sums it up. We hope it’s helpful.

What sources have you used to get reliable information? And do you trust your gut feeling?