On our arrival in Japan, on the southern island of Kyushu, we needed to plot a general route for the coming months. We skimmed our two guidebooks and marked the possible-of-interest places on our Reise Know-How roadmap.

Local information is always a welcome addition and Japan, we quickly learned, has a super-organized system of tourist information centers. You will find their counters in train and bus stations and in michi-no-ekis. These road stations offer a number of things to travelers: a parking lot where you can camp for the night, public toilets, a store selling local produce and handicrafts, and either a shelf with brochures or a counter where you can ask for maps and get information about local places/activities of interest. Whenever we enter a new region, the first thing we look out for is a michi-no-eki.

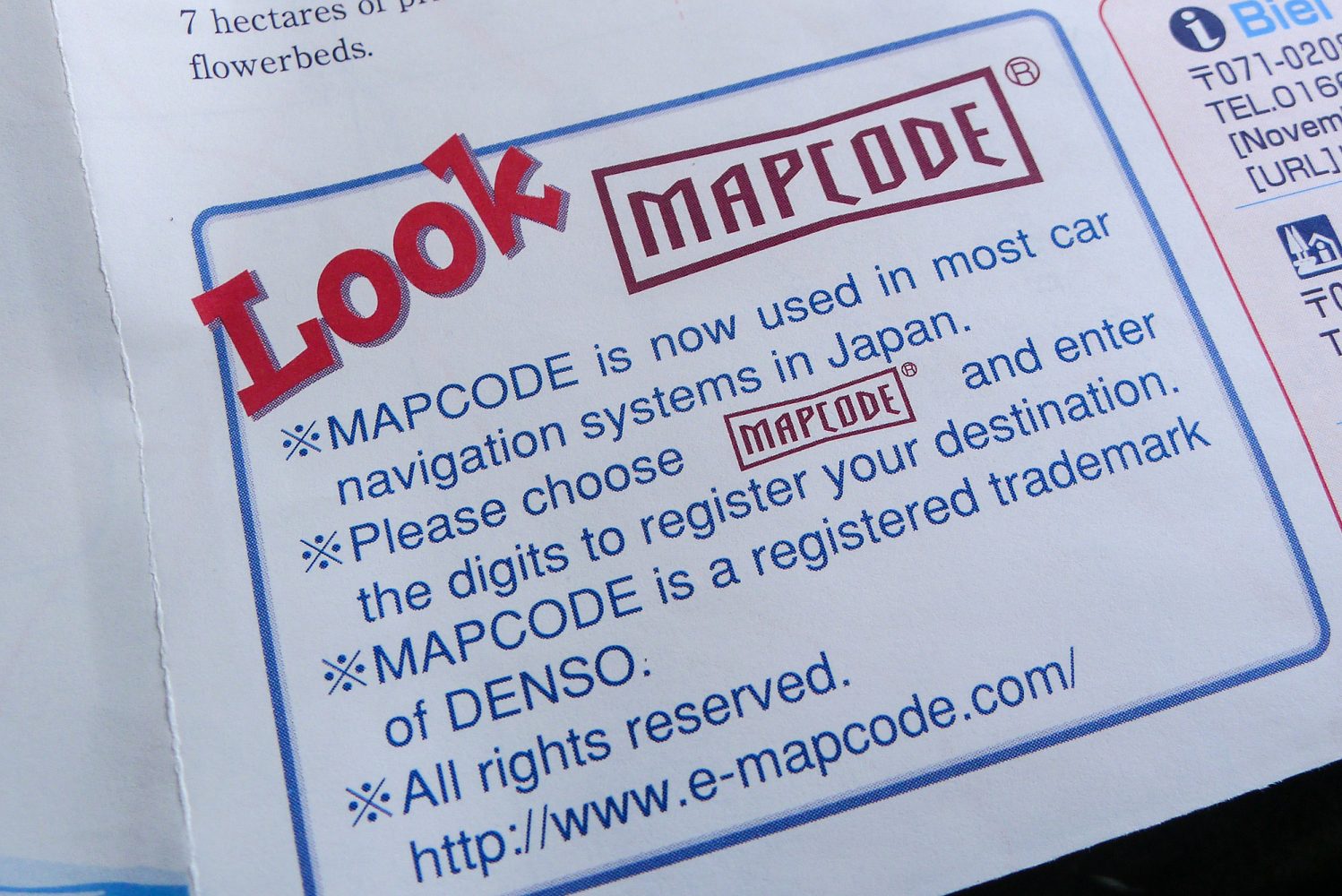

Japanese MapCodes

“Wow, awesome! Where is that? We have to go there!” Often these are Karin-Marijke’s first exclamations when browsing through flyers. The address is most likely in Japanese, followed by a telephone number and a yellow icon called “MapCode” that comes with a six-to-ten digit number. Karin-Marijke has never cared for mathematics, so she will hand the flyer to me. “See if you can find out where it is.”

Most Japanese cars come with an integrated GPS system. You type a telephone number or a MapCode—both being common location identifiers in this country—into your GPS and you are on your way. Unfortunately, that doesn’t work for us. I haven’t been able to convert a MapCode or a telephone number into a more useful (to us) WGS 84 coordinate (a latitude and longitude) when offline. The last part—offline—is where the problem lies.

The international WGS 84 system

When we left the Netherlands in 2003, I brought my Garmin eTreks that I had used on motorcycle trips. It contained no maps, only waypoints. It stayed buried in the bowels of the Land Cruiser for a year or so until we met other overlanders and discovered the advantage of exchanging coordinates of camping spots. We used the standard degrees, minutes, seconds notation (DD°MM’SS.s”) when we needed to share a specific location with someone. It makes sense to use this notation as it relates very closely to paper maps that include degree lines. You can pinpoint locations roughly on a paper map without any problems.

However, this way of notation is prone to errors, both when writing down the unwieldy minutes and seconds punctuations as well as when copying them. Especially when working in HTML, I encountered problems because the degree symbol didn’t always play along nicely.

I also wasn’t aware of the fact that there were more ways of notation until someone gave me the coordinates of a canoe center in Patagonia, and I couldn’t find it. We drove up and down several times without finding the large barn. It turned out that the coordinates were in degrees, minutes only and I used a calculator to translate them. I could have switched the settings of the old Garmin, but since in this case it was only one coordinate, a calculator was quicker.

N 50°45.270’, E 6°1.266’

and

N 50°45’16.2”, E 6°1’16”

They depict the same location but are written in different notation forms.

Shortly after that we switched to yet another notation: the degrees-only format, which looks like this:

50.75450, 6.02110

Local systems

Fast forward a few years. Meanwhile, we discarded GPS units altogether and have been using an iPhone 5. We have continued to use the degrees-only notation, as it is the most copy-friendly system available. Then we reached Japan. Here I was confronted with MapCodes. The Denso MapCode system was developed in 1997 by Denso Corporation for Japanese navigation systems. There was, and is, a market for this system because house numbers in this country are often based on the age of a building rather than being sequential, making it difficult to find a location even when you know the address.

It makes sense to have a system that minimizes the error margin. In Japan, they have found this system by using phone numbers as well as MapCodes: just one number instead of latitude and longitude numbers. The downside, as said before, is that it works only in dedicated Japanese GPS and car navigation systems. We have a similar system for dedicated units in the Netherlands where you punch in a zip code and a house number. I can imagine other countries having their own systems that perfectly work within that country.

International Map-coding systems

So how do I, as a traveler, deal with this? On my search to convert MapCode into degrees while offline, I stumbled on another MapCode system, developed in 2001 by TomTom’s Pieter Geelen and Harold Goddijn. “Mapcodes is an important development in creating a new global standard that makes it easy for anyone to pinpoint any location,” said Harold Goddijn, TomTom CEO.

Furthermore, I recently received an email from What3words. Richard Lewis wrote, “What3words is a universal addressing system. We have divided the world into a grid of 3m x 3m squares and given each one a unique 3-word address. There are 57 trillion squares covering the whole world’s surface and all of them have been named.”

I was totally into the game and spent an afternoon online finding out more about it. To my surprise I came across a number of companies all doing the same thing: TomTom’s Mapcode, What3words, the Natural Area Coding System, M.G.R.S, UBI and Google’s Open Location Codes.

They are all trying to find a way to name locations so an understanding of latitude and longitude is no longer required, and the use of positive and negative grid values is eliminated. They are targeting countries that don’t have an effective addressing system but do have emergency services that need to be able to reach the remotest places, while probably depending on communication via bad connections. They emphasize the ease of using and memorizing their short codes and naming, in contrast to the difficulties that are encountered when using the good old WGS 84 coordinate.

The crux of the matter

I came across a striking clarification from Dr. Mike. “Although I have never tried to memorize coordinate pairs, I agree that lat/lon coordinates might be hard to remember. Of course, so is memorizing and retaining the correct form of a random concatenation of 3 words from a 40,000-word dictionary that creates approximately 57 trillion unique variations of these coordinate triplets.

Perhaps more to the point, I cannot remember the last time I focused on remembering a specific lat/lon coordinate. However, I use lat/lon almost daily, but this action has been made opaque by mapping and finding technology. In my daily life, I no longer need an address for others to find me. I can call up a Google map and by tapping into my GPS chip it can calculate my location and tell others how to find me.

Indeed, if I point at a location on a map in Google Maps, right click and query, “What’s Here,” I receive the lat/lon of that location. If I put that lat/lon in a signature block, it would allow people to find me who did not know my postal address. In fact, the finding action in the above example seems to roughly approximate the same procedure people have to use to find the three-word coordinates in w3w that define the a lat/lon coordinate.”

He continues with, “While the concepts of “finding” and “finding grids” might be considered a global problem, providing addresses for individuals and their businesses may, in fact, be an opportunity that is best considered a local problem.”

What would work, for locals and foreigners?

That last point is exactly our issue at hand. To circumvent the local system of house numbers not being sequential, the Denso MapCodes were invented and are used in all Japanese car navigation systems. It works perfectly, but for a foreigner using an iPhone as means of navigating these MapCodes are pretty useless, unless you are connected to the Internet and can find a way to reverse calculate these codes into a WGS 84 coordinate, which I still haven’t been able to do.

While new-kids-on-the-block are trying to achieve a similar thing as Denso did in Japan, it won’t help a foreign traveler. All these companies use their own proprietary naming system, without providing any sort of standard. Their systems are not interchangeable and in order to use or convert them you need to be online. For navigating they will point to Apple’s Maps or Google’s Maps on the iPhone and I haven’t found a way to get a WGS 84 coordinate out of them either.

I thought technological advancement was there to aid instead of confuse, but I have the feeling things are not getting easier, only more complicated.

Wouldn’t it be great if all the navigation apps could handle all the different input variations? Or even better, if there was an app in which you could enter a geolocation in any format and have it spat out in your favorite notation? While being offline, of course.

Is new always better?

Imagine yourself lost in the great Sahara Desert: Your electronic equipment is out of juice, and you drank your last bottle of water. However, you happen to have a guidebook with latitude/longitude references to an oasis. You get out your paper, grid map, pencils, and a compass and you are on your way.

Now envision the same happening and you have a guidebook in which the oasis is referenced to in three words. Even if it would be aptly called Quench.That.Thirst, you’d still be lost and you wouldn’t be able to find your way.

Meanwhile…

As a global traveler, I adapt and that means I have installed a Japanese car navigation system in our Land Cruiser. Just kidding. No, of course not. The way to deal with this is to go back to old-school navigating and ask people for directions. I will show them the tourist leaflet and ask the Japanese to pinpoint it on our paper map or the digital map on my iPhone. As a bonus we get to practice our Japanese for free. – CW

Read more adventures from Landcruising Adventure by clicking on the banner below: