After a six-day off-road journey through Los Llanos in Colombia we arrived at the border crossing of Puerto Carreño, confident we’d be able to find a way to cross the river into Venezuela (read about it here). More than four days later we hadn’t even come close to getting the necessary stamps and our record for the longest border crossing (2 days thus far) was pulverised.

Day 5 – The Waiting Game Continues

As a result of Venezuela being one hour ahead of Colombia, combined with numerous delays and waits, I did not arrive at the Seniat office in Puerto Ayacucho until around ten thirty. Here I was stalled further and informed to return after lunch. I walked about to find some food and information about the local exchange rate, and made sure I was back at 2pm to seek out Maria, who was Chief of Operations.

She then dropped the bombshell with additional requirements, some of which I knew no other overlanders with foreign vehicles entering on a Temporary Import Document had had to deal with at other border crossings with Venezuela. Among the demands was a paper stating the value of our Land Cruiser as well as a payment of one percent of that value into the Customs’ account. I couldn’t give them that paper, as Dutch car papers never mention value.

I asked to speak to the Chief of Chiefs, Mr. Franklin, and was asked to wait, wait and wait some more. By the time everybody started to pack up and leave they told me to return the next day. It was 5pm and by then the last speedboat had left. So I bused to the main bus station where I found an overpriced shared taxi to the bongos at El Burro some 60 miles north.

Halfway I was picked out by an immigration officer at a military checkpoint. I then realized I had forgotten to stamp out at the immigration office in Puerto Ayacucho.

“Adonde vas?” Where are you going?

“I was hoping to get back to Colombia, where my wife is waiting.”

“But you haven’t stamped out of Venezuela. You cannot leave!”

“I’ll be back tomorrow as I’m working on getting my car into your beautiful country. Can’t I just cross the river and I will not stamp in at the other side either?”

“Hmm, you could be in big trouble if the marine guards catch you. Your call.”

“I’ll risk it,” I answered.

“Okay, I’ll let you off the hook. But be sure to properly stamp out and in tomorrow.”

Pfew. Off we went. Finding a fisherman who dared sneak past the marine guards at dusk with an illegal alien wasn’t at all a matter of course, but I managed to find one and by 10pm I was back with Karin-Marijke.

Day 6 – The Power Play

Not taking any chances by landing at the official border crossing of Puerto Ayacucho as I was not stamped in, I took the long way around via Puerto Paez (the way I had come the night before), hoping I wasn’t going to be checked on the Meta River crossing. It went as planned until I was confronted by a mobile military check on the Venezuelan shore. It took me an hour to get through the queue caused by extensive luggage searches. When it was my turn I kept my non-stamped passport in my pocket. Strangely, and luckily enough, they accepted my laminated copied passport as ID and waved me through.

The shared taxi dropped me off at the Seniat office. This time they enlightened me that I would not get a stamp to bring our Land Cruiser into Venezuela. I was baffled. So many of our friends had easily entered the country either coming from Brazil or at the more northern Colombian border crossings. Here it seemed they wanted to deal with their incompetence by sending me away.

However, I have an unwavering tenacity when it comes to red-tape procedures and I wasn’t about to give up. I asked for the boss who made me wait until the end of the day while I sat underneath a poster claiming ‘Efficiency and Transparency’. It became a power play and at six I was told, once more, that the boss had no time for me. I exploded, shouting some nasty things about this so called efficiency and transparency, and left the office fuming.

Another day lost in waiting and another long return: by bus to the terminal, by shared taxi the 60 miles to El Burro, a bongo across the Orinoco, a motorcycle zigzagging through Puerto Paez, a second bongo across the Meta River, a walk downtown to the bomberos. By then it was, again, 10pm.

Who says overlanding is nothing but an extended holiday?

Day 7 – Hope

I met an angel by the name of Richard, of the Seniat’s ‘Legal Department’. He had heard my tirade the day before and it had kept him awake that night as he searched for a solution. He turned out to be the only man on this side of the border who cared about our journey and wanted to help. He did his best, but throughout the morning I saw how he was sent from pillar to post as well.

Another couple of hours lost in waiting. By then my spirits had sunk so low I finally gave up and threw in the towel. They had won.

I was about to leave when I discovered that, two days earlier, I had handed my original Impronta de Sijin to the Seniat, instead of a copy. Stupid! I wanted it back though, and asked for it at the counter. The clerk asked the Big Boss for it who, for reasons unexplained, all of a sudden was willing to try and find a solution.

“Organize your local insurance, which you’ll need anyway. This will settle the issue of the value of your car, giving us a way to deal with that one percent tax as well,” he suggested.

Feeling hopeful again I took a bus downtown, found an agency and bought a third-party insurance. When the desk clerk was about to finish registering everything in her computer there was a power cut.

“Return tomorrow.” Mañana, mañana – have I ever hated those words more than during this week?!

Day 8 – Insurance

Meanwhile it was Saturday. Karin-Marijke and I returned to Puerto Ayacucho once more and organized the insurance. The document stated that in case of an accident the maximum compensation would be a mere 30,000 bolivianos, the equivalent of about 200 US dollars. The value of our car, however, wasn’t stated anywhere. This would surely give the Seniat reason enough to put more obstacles in my path.

We agreed I would give it one last shot on Monday. If then the Seniat would continue to be obstructive, we would give up and drive the 930 miles to the Cucuta border crossing.

Day 9 – Sleep

I took a day off – Sunday – to sleep.

Day 10 – Papers!

It is hard to believe, let alone understand, how a situation can turn around so quickly. All of a sudden the Seniat agreed to the Land Cruiser’s value of US $5000, which I had initially mentioned but which they had wanted to see stated on an official piece of paper. They now handed me another document to sign, by which time it was 2pm. This gave me exactly one hour to take a bus to the bank and pay that one percent tax.

For once things went smoothly. While the bank transaction took place I met a woman who gave me her card after she had offered me the best exchange value for US dollars thus far. On our arrival in Venezuela – which was really about to happen – we’d call her to change money (which eventually we did and her efficiency stood in stark contrast to anything Venezuelan we had experienced thus far).

Day 11, 12, 13 – The Crossing

With matters on the Venezuelan side in order, at last, I returned to my challenge on the Colombian side: Milamores. There was nothing for it but to accept his scandalous fee. His mañana, mañana was followed by more mañana, mañana, but finally, things were happening on this side as well.

We agreed to meet at the docks at 7am. Unsurprisingly, Milamores wasn’t there, plus now Karin-Marijke was about to back out the moment she spotted the boat on which we were about to cross.

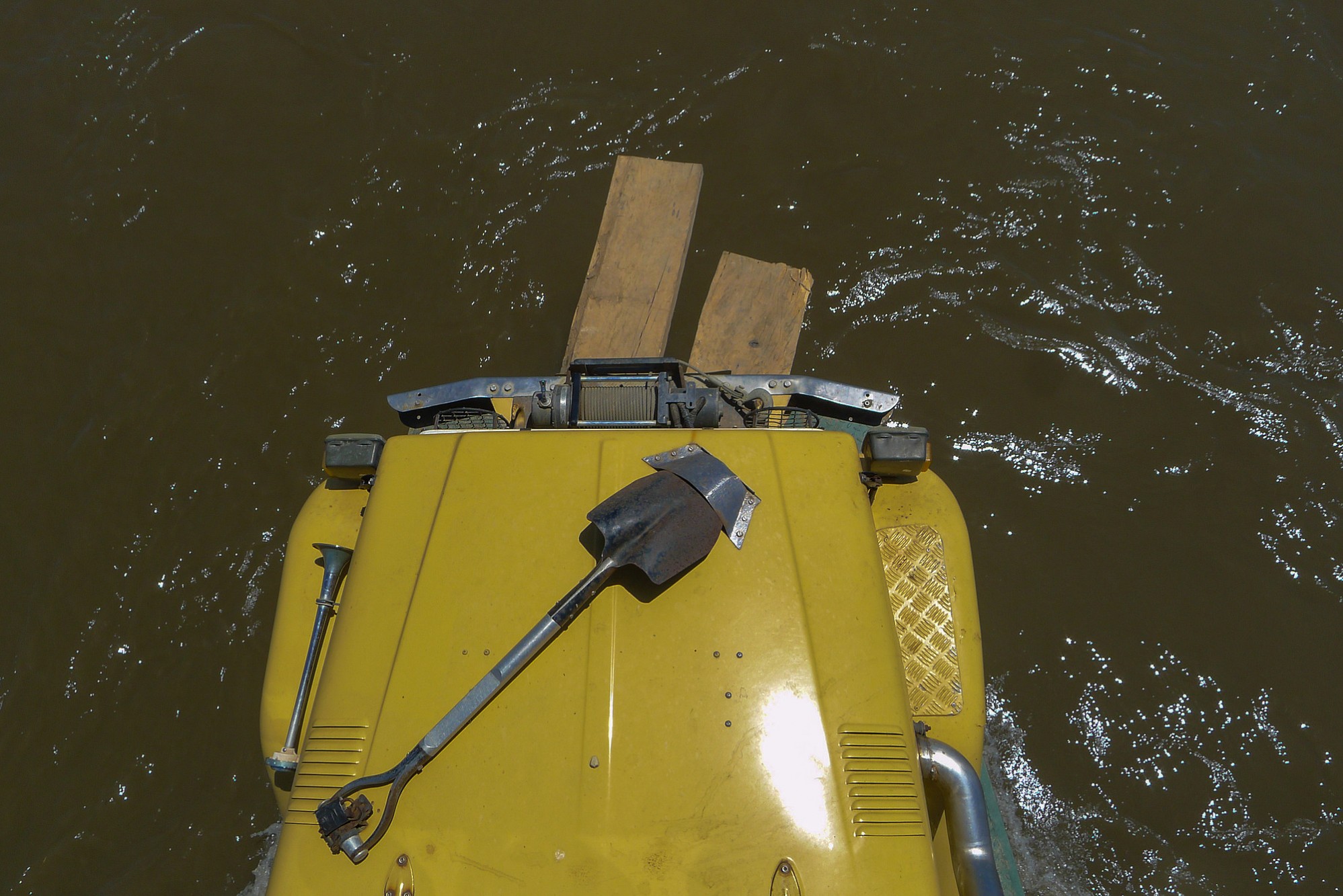

“Are you mad? We are not going to cross on this!” She was livid. Truth be said, I had not paid attention to the actual boat and this was the first time I saw it too. And, truth be said again, in her shoes I would not have been confident either, but I had seen photos of the barge carrying a tractor across.

“It’s used to carry tons of cargo,” I argued.

“Where do we put the car?” she asked.

“On the front deck,” I answered.

Of course that sounded improbable – it was about the size of our vehicle, if that.

I called Milamores – again. “Fifteen minutes,” he answered. Meanwhile mechanics were fixing a broken truck uphill that needed to be able to drive closer to the boat before the boat’s cargo could be unloaded, and only then could our vehicle embark.

By 9am the truck was fixed and the crew had unloaded 30 tons of rice. They put two planks in front of the boat as a ramp and Milamores, who had finally shown up, guided me onto the boat in one go. There were about four inches of space left on each side of the Land Cruiser. There now were three tons on the front of an otherwise empty boat and as a result it got stuck on the sandy bank. For an hour the crew pulled and pushed, but the outboard engine was too weak to free the boat. They solved it by filling the cargo space with two tons of water. The boat regained its equilibrium and got free.

As the boat was about to get free I asked Milamores for his papers of the Capitania, which still need to be signed (by the Capitania) before they would allow us to leave. He knew nothing about papers – sigh – and set off to organize them. On his return he stated we wouldn’t be allowed to leave as there were no import/export documents.

Off I went, taking, once again, matters in my own hand. At the Capitania I explained how this was a transit issue, not import or export. It took some convincing but towards the end of the morning I finally got the Capitania to sign a paper clearing the boat out of port. Next door I sweet-talked a customs officer into coming with me, inspect Milamores’ boat and our Land Cruiser, take photos as proof and nullify the Temporary Import Document.

We were off!

And now you think we made it into Venezuela without any further hiccups, right?

Wrong.

Reaching Venezuela, or not?

While Puerto Carreño had at least something that resembled a port, at Puerto Paez there was nothing but an overgrown riverbank. Parts were unaccessible due to vegetation and Milamores decided to dock at a patch of bare rocks. The boat was pushed sideways due to the strong current and frankly we were a bit worried about capsizing.

We managed to reach the shore where I walked up the rocky surface, checking if we’d be able to leave this place to get to any form of civilization. I feared large cemented walls would keep us trapped after Millamores had dropped us here and disappeared into the sunset with his boat. My confidence in others had sunk a little over the past two weeks! Fortunately, this was not the case but thank god we have a Land Cruiser because without 4WD we would not have been able to rock-crawl up that hill.

As I returned to the boat I saw the boatsman making a miscalculation and the boat, with Land Cruiser and Karin-Marijke, got swept away towards an area full of whirlpools. My stomach turned and I shouted to Karin-Marijke to pull the handbrake, to put her full weight on the brakes and to not suddenly shift weight. I didn’t know if she could hear me and hoped for the best. The outboard engine was roaring at full power. To my great relief I saw the boatsman realized what he was doing and ten minutes later he managed to bring the boat safely to the bank again.

All this left enough time for more officials to appear out of nowhere on this spot in the middle of nowhere: soldiers. What were we doing here?! We were not allowed to be here! I stifled a shriek of despair. It was not that they were unkind. They were just doing their job but my patience had run very low and it took quite an effort not to scream, “Please, stop with all this nonsense!” It would have been useless, or worse, worked against me.

So, another deep breath and some more talking and cajoling. We were instructed to show our papers in Puerto Paez at yet another office – they would escort us there.

In low gearing I maneuvered the Land Cruiser up the rocks, through vegetation, to an asphalted road, and stopped at the office. They wanted copies. Right. Off I went on a wild goose chase to find a working Xerox machine – there was precisely one to be found. However, there had just been another power cut, which was a daily occurrence in this country that was going deeper down the drain each day. And so we couldn’t make copies.

By now you know what followed: yet more talking, yet more cajoling. Finally they let us go, trusting us to return the next day with some copies (which we did) and then we set ourselves to our last task: driving the 60 miles south to Puerto Ayacucho, which I had driven so often the last few days in shared taxies, to the immigration office where we finally got our visa stamps in our passports.

At last, we could start our exploration of Venezuela.

Read this article and many more at: [Click on the banner]