Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in Overland Journal, Gear Guide 2011.

The year was 1982, and my parents packed up my sister and me in the car and headed north. It was a typical family road-trip vacation to my knowledge at the time, and it would be many years before I found out it could be done any differently. Leaving the city by the major highway, we motored north and west, watching for speed traps and smelling acrid smoke from continual grass burns on the verge. Eventually, we left the highway and moved to secondary roads as we approached the border. North of the line, the roads degraded until, at a small town called Molepolole, we hit dirt and, after a very cold night camping by the side of the road, set off into the Kalahari Desert.

Moving north on dirt tracks, with little to no traffic other than donkey carts and the odd cow, we reached the vet fence that bisects the Kalahari (supposedly to prevent the spread of disease from wildlife to livestock), and were witness to what has been estimated at 50,000 wildebeest dying along the fence line, something that has had a significant and lasting impact on me. We camped on the shores of Lake Xau before turning slightly west towards Maun and the Boteti river.

On a dusty desert track, the question of our position was raised by my mother, to which my father indicated we just had to travel north to the river. The compass was on top of the transmission, its needle making lazy circles rather than indicating any specific direction. Tensions got higher, but eventually, the river revealed itself and we camped on its shores, our sleeping bags tucked inside dog-repellent trash bags to ward off roaming crocodiles. (Still not sure if that one works, though I still have feet.) Finally, we reached the end goal of the trip, after we passed Maun—the Moremi Game Reserve. Back in those days, there were no established camps, and visitors could camp where they found a spot. There were no fences, so wildlife was quite free to investigate you at any time. We had no roof-top tent, but rather slept under an awning guyed out from the side of the car, a small fire kept alight all night to ward off large cats and hyenas. Unfortunately, elephants didn’t seem to mind the fire and would pull the guy lines out of the ground as they ambled past, dropping the whole caboodle on our fast-waking forms.

Leaving Moremi after several days, we started south across the enormous Makgadikgaki Pan, raising a wake of white dust behind us. At one point, parked for lunch next to a large baobab, my sister and I etched ‘MMBA’ in the dust on the back window of the car: ‘miles and miles of bloody Africa,’ now established as the tagline for the trip.

Which brings me to the vehicle we were in and the reason for this whole story. It was a 1973 two-door Range Rover, in Maasai Red, powered by a 3.5L V8 and manual transmission, with minimal interior appointments (since none were available in that year). To a boy of 10, as I was at the time, the Range Rover was awe-inspiring. The many miles of rough roads, the soft sand of the desert, the massive load of fuel and equipment we carried, and not a single problem apart from punctures. I was already a Land Rover fan, but that trip galvanized my appreciation for the marque, something that has not waned since. I refined my taste from the Range Rover to the Defender, but have always had a hankering for the old Rangie. Of course, my idea of the Range Rover is not typical. Not a mall crawler, not a luxury vehicle, not what Land Rover North America sells, but rather a tough, capable, and comfortable expedition platform. And that is what this build is all about—getting back to the heart of the Range Rover. Over the course of several articles, I’ll explore what it takes to turn a luxury SUV into my idea of the perfect mid-range overlander.

Goals

So first to establish some goals. I’m a big believer in diesels for expedition use, both for reliability and for economy, which translates to range. I’m also leery of too many electronic systems, especially in older vehicles, as that seems to be where problems first crop up. Luxury appointments usually add more weight than luxury, and keeping an expedition truck as light as possible should be a primary goal. At the end of this project, I hope to have a reliable, competent vehicle that is comfortable, simple to work on, and doesn’t break the bank during the build.

The truck for the project was very kindly donated by Land Rover Las Vegas. It’s a 1995 short-wheelbase Range Rover Classic, the very last of the classic line. Certainly not the same as the two-door we had in Africa, but a direct descendant. From the factory it came Epsom green, with leather seats, sunroof, air suspension, automatic transmission (as with all North American Specification Range Rovers), Borg Warner transfer case with viscous center differential, and the 3.9-liter version of the Rover V8. It spent years under the Nevada sun, so the clear coat is ruined and the paint faded. The two front seats were torn and stained, and the electronic adjusters had failed. Desecrating the load bay was a massive home-made structure containing two 22-inch sub-woofers and two amplifiers, the sort of thing you might expect at an impromptu rap concert in an alley.

Why a Range Rover?

The choice of a 1995 Range Rover was far from arbitrary. That model year has several distinct advantages with regards to this project. To start with, the bulkhead and dashboard closely match the Land Rover Discovery Series I, so some parts are interchangeable across the two models. The 300tdi 2.5-liter diesel was offered in European versions of the Range Rover, and I already had a full 300tdi drivetrain. 1996 saw the entry of OBDII requirements for US emissions, so 1995 will be the last easy model year to get a diesel transplant emissions-certified without catalytic converters and OBDII sensor requirements.

Diesel Conversion

Embarking on a diesel conversion should not be taken lightly. So often conversions end up causing more problems than they solve, as vehicle systems are disabled and engines end up with inadequate cooling or electronic support. A good way to mitigate these issues is to install a drivetrain that was offered in the model by the manufacturer—that way factory components fit, and both electrical and mechanical systems match. Since the 300tdi was offered in the European 1995 Range Rover, engine placement is easy, although it requires welding new engine mounts on the frame and installing a new frame cross member with the appropriate manual transmission mounts.

I’m very lucky to count Keith Kreutzer from RoverTracks as a good friend, someone willing to allow me to park the Range Rover at his house for the duration of the drivetrain transplant. Truth be told, we think we could complete it in one weekend if all the parts were on hand. But don’t ask Keith to put a diesel in your Land Rover; he’ll help you, but he’s not a conversion shop.

Conversion Mechanics

The mechanics of the conversion are easy. The pedal assembly, including the clutch master cylinder, swaps directly from a Discovery. We removed the Wabco ABS pump, a problematic and expensive system on the 1995 Range Rover, and went back to regular power-assist brakes from a 1989 Range Rover. This eliminated both ABS and traction control. The transmission and transfer case dropped right in with the correct crossmember and factory diesel mounts, which are very important for vibration isolation. The propeller shafts from the Borg Warner transfer case are too long for the LT230 case, so I got custom shafts from Tom Woods, including a double cardon for the front shaft to deal with vibrations after the suspension lift, and a U-joint conversion for the rear pinion, where Land Rover had the troublesome rotoflex.

Electronics

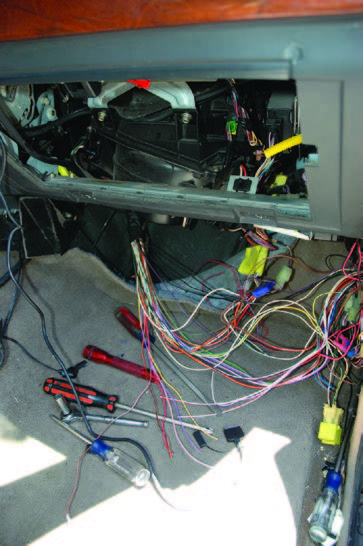

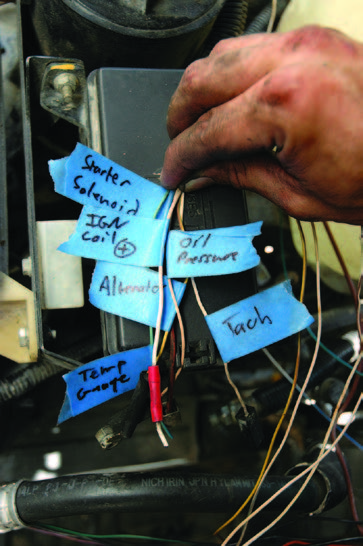

The electronics for the engine conversion take some work. All the engine management electronics, including the ECU go away. The new engine harness is made up of exactly six wires: starter solenoid, oil pressure, temperature, alternator, tachometer, and the ignition coil wire (which becomes the fuel solenoid wire on the diesel). For the transmission, the reverse lights have to be separated from the transmission harness and run to the correct position on the R380. The wires for the park/neutral position switch have to be connected so that the car will start, since on an automatic starting is disallowed if the transmission is in any position other than neutral or park. We pulled all the other wires on the engine harness except the air conditioner switch and a few power lines, which will be used for accessories later. After the conversion, Keith was able to source a 300tdi air conditioning kit, which included the compressor, idler, adjuster and the belt. All have been added to the engine, but the lines have not been completed yet.

Fuel

On the fuel side, the electric fuel pump has to be removed from the tank, and a longer pickup line installed. Then it’s just a matter of making sure that the supply line and return line are hooked up correctly on the injection pump.

After getting the drivetrain in, it was just a matter of completing the inside with the center console and shifter boots, and tying up a few loose ends, such as eliminating the alarms and interlocks for the Borg Warner transfer case and the automatic transmission. Replacing the seats with cloth versions sourced from RoverDude was a straight swap.

Suspension

The air suspension had already been replaced with Land Rover factory springs when I got the truck, but I went one step further and installed an Old Man Emu kit from ARB. The medium-duty Range Rover springs and the new Nitrocharger Sport shocks installed easily, and give a firm ride and a two-and-a-half-inch lift with the truck in its current light state. Jeff Corwin of JC’s Rovers in Denver supplied me with a couple of pre-air-suspension shock towers for the front. Once other accessories have been added, I’ll revisit the suspension and make sure it matches the load and sits level.

Stage one result

So now I have a turbodiesel, manual-transmission Range Rover in mostly stock form. There are a few details left on the conversion, and then the modifications for expedition work. Will I take this Range Rover through Botswana? No, probably not, but, as Land Rover would like everyone to believe, I could.