It seems like whenever it comes up in conversation that we’ve just driven our van around the world, and that to do so took nearly three years, the first thing people say is something along the lines of “That sounds expensive!” I can see why people might think that. I mean, we used to take ten day vacations to Europe, and when we would return our bank account would sometimes be $5,000 less than when we left. There were the plane tickets, the buses and trains, hotels, restaurants, and entertainment. That’s not to mention the fact that the cost ticker on rent and bills never stopped ticking while we were away. So yeah, Jesus H. Christ, if it costs $5,000 for a ten day international vacation, it must cost, like, a cool half million to do it for three straight years!

But it doesn’t. So how much does it cost to drive around the world in a car? The short answer is: far less than it costs to stay home. If that doesn’t make you feel like you’re missing out on something, it should. I’m sitting in my house right now, thinking about the fact that our yearly rent on this studio apartment in Seattle is nearly as much as our yearly cost to drive around the world.

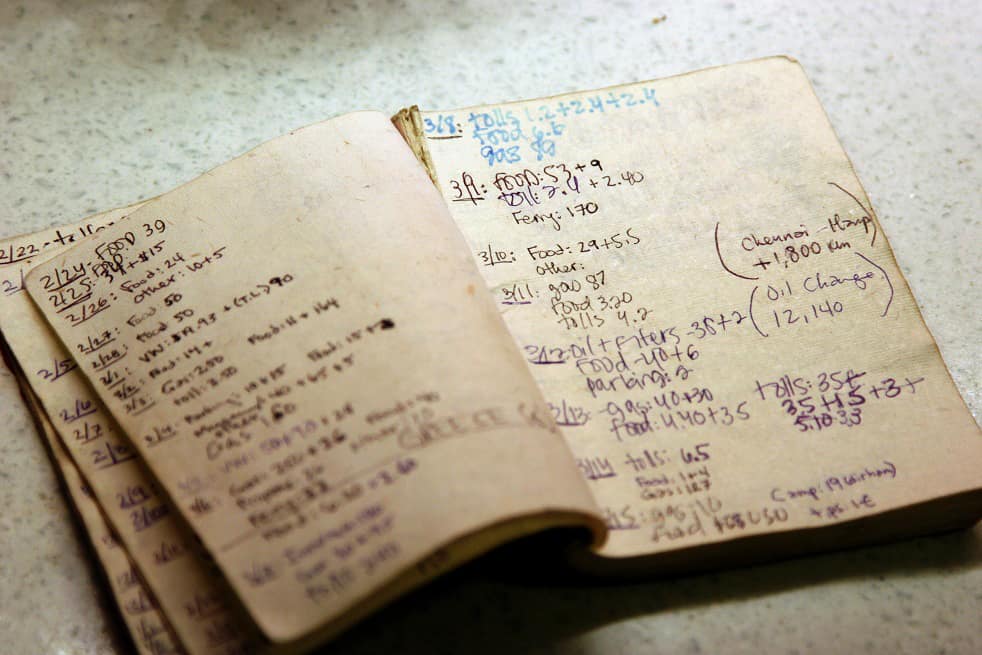

Before we jump into the numbers, a quick note on cost accounting methodology while on the road. We were gone for 927 days, and we tracked every single penny that we spent. And we didn’t do it with fancy online bank tracking tools, as that would have been impossible since we paid cash for 99.9% of our expenses. Even for big bills like shipping our van on container ships across the oceans. And no, we didn’t use a fancy smart phone app either. That would have been impossible on account of the fact that we didn’t have any phone at all most of the time. No need to adulterate a perfectly good adventure with a telephone.

That’s another thing that seems to surprise people: we didn’t have a phone for three years, and it was absolutely fan-freakin’-tastic. But I digress.

No, we tracked our expenses by writing them down with a pen in a small notebook that I kept in my pocket throughout the entire trip. I don’t even know how many of these notebooks I went through. Every week or so we would transcribe the information from the notebook into a spreadsheet I created that tracked our categorized expenses. It told us whether we were on track with our budget, and extrapolated our expenditures to estimate how much we’d have left at the end of the trip. Tracking our expenses to this level proved invaluable in staying on track on such a long trip.

With that out of the way, we can get down to the rice and beans of this affair. There are a lot of ways to slice this data, so I’ve prepared it in a few different ways. This is how I’ve broken it down in sections:

1Summary of expenses

2Cost breakdown by country

3Detailed costs by month

Without further ado…

Summary of Expenses

In this section I’ve summarized all of our relevant trip stats and categorized expense data. It should be noted that these costs include everything; food, gas, lodging, vehicle shipping, insurance, flights, repairs. If we were to remove costs for shipping the van, flying from continent to continent, and replacing our engine, for example, the average daily cost would be greatly reduced. It would be much cheaper to stay on a single continent, but that wasn’t the point of this trip. This was our total cost to survive.

Total days in trip: 927

Total countries: 34

Cost per day: $102

Mean cost per month: $3,102

Mean cost per year: $37,224

Total cost of trip: $94,524

Highest month: $7,462 (Argentina)*

Lowest month: $1,245 (India)

*Includes shipping van from Argentina to Malaysia, flights from Argentina to USA to Malaysia, and the fee to get our Carnet de Passages for Nacho.

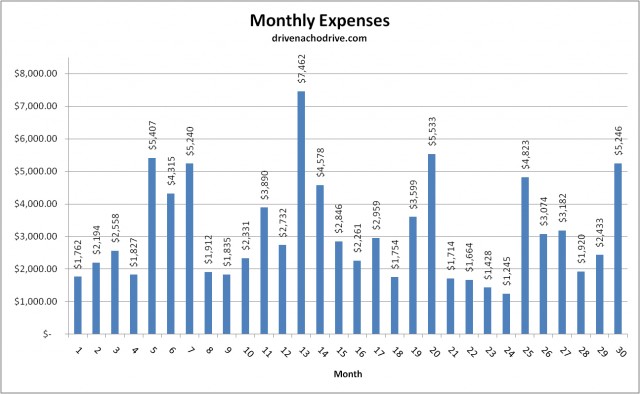

Here’s how the cost played out, month by month. Notice that there are a few very high outliers (due to incidentals like shipping the van/flying ourselves, replacing our engine, and the whole transmission smuggling debacle). Our costs were generally around $2,000 per month when we were just living and driving.

And here are the total costs broken down by category over the course of the entire trip, ordered from high to low.

Food: $23,064 ($756/mo)

Shipping/Flights: $19,885 ($652/mo)

Gas: $13,874 ($455/mo)

Other: $13,293 ($436/mo)

VW Expenses: $11,293* ($370/mo)

Hotels/Apartments: $5,383** ($176/mo)

Transport/Parking/Tolls: $2,391 ($78/mo)

Entertainment/Entry fees: $2,092 ($69/mo)

Borders/Visas/Permits: $2,043 ($67/mo)

Camping: $1,454*** ($48/mo)

*This was for anything we spent on the van; from small things like oil/filters, to big items like the engine transplant in Thailand and transmission replacement in Colombia.

**We rarely stayed in hotels, but occasionally we would rent an apartment for a month. The reason for doing so usually had to do with waiting on the shipping process, but it was always a welcome recharge.

***We almost exclusively “wild camped,” or “boondocked,” which is free, as we usually found it preferable to the confinement of campgrounds. Once we hit Asia there were virtually no campgrounds anyway, and when we got to Europe they were too expensive to consider.

Cost Breakdown by Country

Even when I tell people how cheap it is to live on the road, they tend not to believe me. I’ve just shown you that we lived rather comfortably on a little more than $37k per year. From an American perspective, that’s a fairly low-cost existence; that’s about the starting pay for a teacher, or half what a typical junior engineer makes in a year.

Now consider it from a different perspective. We were living primarily in third world countries where the cost of living is directly proportional to the income of the population. In Mexico, the average monthly income is only $375. Therefore, it is possible to survive in Mexico on $375 per month. Obviously we have some extra expenses like gasoline and road tolls, and we tend to spend more on food and entertainment, but it makes the $1,900 that we spent per month in Mexico seem preposterously excessive. Now consider that the average monthly wage in Nepal is just $37, and the $1,400 per month that we spent there is downright lavish.

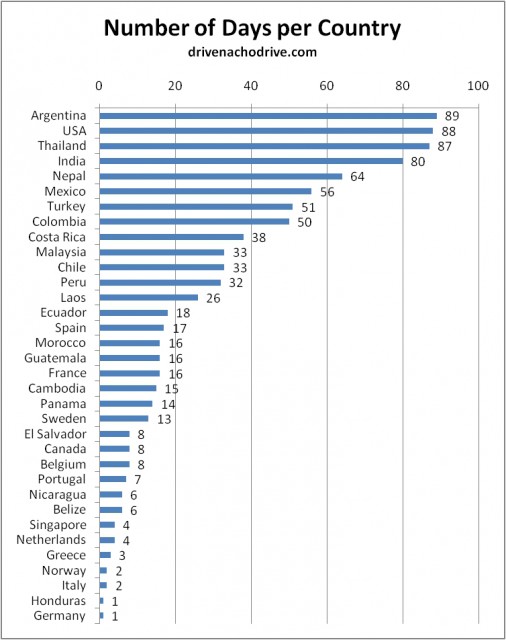

Before looking at the cost, here’s a list of which countries we visited, ordered by the amount of time we spent in each country. Keep in mind that our average daily costs for countries with a greater number of days will paint a more accurate picture of the real cost to travel there, as it will draw from a greater sample size.

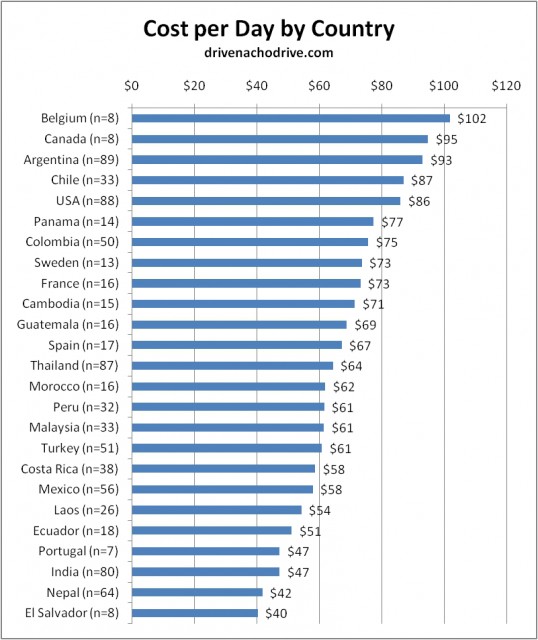

To get an idea of how much it cost for us to live in each country, for the next graph I’ve removed the major outliers for things that don’t relate to living expenses; namely, shipping, flights, and major van repairs. Think of this as the cost for us to overland within each of these countries once we were already there.

For this chart, I removed all countries for which we didn’t have data for at least one week. Countries with higher sample sizes will naturally have higher accuracy. For example, Panama is a pretty cheap country, but since we spent most of our time there preparing for shipping, we had some higher costs than if we were only exploring. If we’d been there longer, it wouldn’t have come up as the 6th costliest country. Conversely, Sweden should have been at the top, but we were there for a short enough time that we were able to hobble by on bread and water while sleeping on Sven’s couch.

Detailed Costs by Month

I mentioned that we transcribed the cost notebook to the spreadsheet every week or so. I’ve taken screen shots of the meaty bits of that spreadsheet for each month—all 31 of them—and have compiled them into great big sheets.

Click the image below to be taken to a page containing one such image for each month. It depicts total cost per category by month.

So we must be rich, right?

All right, so we’ve established that we drove around the world for nearly three years on $94,000. And while that’s much less than most of us Americans will spend in three years of sitting around at home, the problem still persists that we can’t drive around the world on $94,000 unless we have $94,000 in our bank account first, right? Right! So how the hell do you get $94,000?

It’s daunting, I know. And you don’t want to come home broke, so it would be prudent to come back with some savings to live on while you plug back into society. So now what? You need an ungodly amount of money to buy your freedom, and only rich people can do that, right? Wrong! We started with very little in savings, just like everyone, and ultimately got the money we needed by saving up. Sounds too hard, I know, but hear me out.

We were making decent money at our jobs (I as a mechanical engineer, Sheena in corporate accounting), but not crazy money. Just regular money. Your standard dual income college-educated professionals on salary. But just like pretty much everyone in America, we had no money left at the end of each month. Maybe we could save a few thousand dollars per year, but it seemed like there was always something popping up to take away our money. But one day I was talking with one of our lab technicians who complained to me that he had only taken home $24,000 the year before, and he was pissed off about income disparity. Of course I felt for him, having grown up in a household like that. But it also occurred to me that he was surviving on $24,000 per year, and he also had no money left at the end of each month, just like me and everyone else. So what were we spending all of our extra money on? In theory, couldn’t we live on $24,000 if we really tried? Don’t millions of Americans already do it?

Quite simply, yes. No matter how much we earn, most of us will spend it all. If only we made a little bit more it would make life so much easier, but the truth is we’d still spend it all. So Sheena and I decided to live like the lab technician and put the rest in a special bank account we set aside, which we called the “Nacho Fund.” Back at the beginning of our trip I wrote about some techniques that we used to save our money. But to summarize, by simplifying our life and living as if we earned a lot less, we were able to survive entirely on Sheena’s salary, while mine went into the Nacho Fund.

In the end, it took us only two and a half years to save not only enough money to buy our freedom, but also enough for a post-trip savings buffer. Honestly, once we made the adjustment to living inexpensively, we sat back and watched the money pour into our account each month while our daily life concurrently became far more enjoyable in its simplicity. It was unreal. And we had never even considered that it could be possible, because before that we were like everyone else, always ending up with nothing.

I do realize that there are people out there for whom this kind of thing isn’t possible, but it’s not as many of you as you think. I hear it all the time, people telling me that it’s nice that we could do it, but there’s no way they could because of X, Y, and Z. But most of them are selling themselves short. If you can think of someone in America who is surviving on less than you are, and you’re willing to make the necessary sacrifices, then you can do it too. And if it will enable you to live the life you want, then I hope you do.

All of us at Expedition Portal would like to extend our genuine gratitude to Brad and Sheena for being so generous and sharing their travels with us. It’s been a fun ride traveling in Nacho vicariously through their beautiful writings and images. We can only imagine what new adventures await. www.drivenachodrive.com