Our plane landed in Chennai in the dark and we exited the airport into a calamitous mess of bodies. Touts hurried from passenger to passenger trying to round up business for the taxis. We were swept up in the chaos and found ourselves cramming into the back of an old Ambassador with a velvet headliner and ornamental drapes hanging above the windshield. The driver gunned it and we heaved into a thick torrent of box trucks and taxis and motorcycles. We fought the urge to fall asleep aboard this Indian death rocket while we listened to our cab mates: a couple of idealistic young hippies who were on their way to becoming enlightened and certified as ayurvedic healers at a meditation retreat with their internet yoga guru.

One hour later we were deposited in front our hotel, a ramshackle heap of brick and mortar that we’d been required to book online in order to receive our Indian visas, and which looked nothing like the pictures, nor did it seem “quaint and inviting.” The cab driver did his best to cheat us out of more than the agreed rate, but failed and drove away with the hippies and their guitar.

The hotel man was kind, and walked us to our room—a mosquito-infested, moldy, dank hole in the corner of the dilapidated building. The beds were hard and clammy, and the air stunk of deep, pungent body odor. It was as if the humidity in the room which soaked the walls and sheets was not water, but a fine mist of rank armpit juice. Throughout the first night I would repeatedly wake up gagging, as if a big sweaty Indian man were smothering my face with his sour, repulsive armpit. This was a rude awakening after five weeks in our posh, fluffy white Bangkok apartment; we weren’t in Kansas any more.

In the morning I sought out a general store that sold incense sticks, and burned them continuously the following evening. Our room had neither mosquito nets nor window screens, so we slept with the windows closed to fend off dengue fever. The room quickly filled with incense smoke, making it hard to breathe, but every time I awoke I was relieved to be asphyxiated by hippie-smelling smoke rather than by a big, wet Indian armpit. When our booking ended in the morning, we hastily moved to a less repulsive hotel.

Out on the street, Chennai could be described as no less than a complete and brutal assault on the senses. There were no in-betweens; the traffic was suicidal and unforgiving, every car continually blasting its eardrum-splitting aftermarket horn; the roadsides, alleys, and street corners were ankle-deep in rotting trash; the street gutters were filled with a black sludge formed by a concoction of human and animal excrement mixed with stagnant water, urine and dust. The sidewalks were unusable, filled with parked motorcycles, shop inventory, or else replaced by deep crevasses filled with black goo.

There was never a time that the place didn’t smell. It fluctuated depending on location, so walking in a straight line brought a rainbow of odors ranging from decomposing garbage, to mutton briyani, to burning plastic, to chana masala, to cow poop and the overwhelming wet odor of copious amounts of human piss baking in the sun. But it never smelled like nothing.

Cows roamed the streets, rested in busy intersections, shat on sidewalks, and swallowed plastic bags like they were weeds while dining on the trash heaps that filled every nook and cranny of the city.

But amid all of the slime and stench and ear-splitting noise, Chennai had a saving grace—it was fascinating. We had found a place with more color and life than any place we’ve ever been. Men with wooden staffs and white robes hobbled down the middle of the street, beautiful sari-clad women traveled in packs, people in cars honked incessantly at one another, but waited patiently as enormous cows sauntered along in front of them.

One night we were awoken from our sleep in the middle of the night by the sound of drums and eerie horns outside. We jumped out of bed and ran downstairs and into the street to see what was going on at such an hour. When we emerged into the empty street, we found a group of men carrying a giant statue of Ganesh the elephant-faced god down the street. A band of musicians walked in front while women twirled around, flapping their vibrantly colored saris in the night air. A shirtless man walked up to us and handed us some sweet pongol in cups, and then the procession left us behind. We ate our pongol, sauntered back upstairs, and fell back asleep, as if it was all part of a dream.

The food in Chennai was life-changing. Every day we emerged from our hotel and found our way to one of the hole-in-the-wall restaurants lining the chaotic streets. Sometimes it was simple, as in the case of Briyani Boy, who had invited me to take his photo. He served mutton briyani into a page from the day’s newspaper, and then we would stand on the sidewalk eating it with our hands. Other times we sat inside of sweltering restaurants while fans pushed the humid air around, and we gorged ourselves on mouthwatering curries and South Indian specialties like dosa, idly, puri, or the all-you-can-eat South Indian thali. Always we ate with our hands—but only the right, as the left hand has a single and kind of gross purpose in India, and is not to come into contact with food. We drank masala tea, served in steel cups and poured back and forth between the cup and deep saucer repeatedly from such high heights to mix and cool it before drinking. And invariably the most expensive entrée on any menu hovered around a dollar or two.

And then there were the people. People watching in Chennai became our favorite pastime while we waited for Nacho to arrive in the port. Each day we would emerge from our hotel with the camera in search of people. Four shops down there was a hole in the wall where men sat around a crude machine. One man cranked a large wheel while another sat on the ground sharpening knives and scissors against a spinning piece of stone. Seeing my camera, they invited me inside, told me the story of how Ghandi used to spin thread for his own clothes, and let me take a bunch of photos. Next door a young man stood proudly in front of his briyani pot, spooning portions into steel bowls for his hungry clients at fifty cents per meal. He asked me to photograph him serving up some briyani, and then offered me lunch. On the next block, peering into an open gate revealed a young girl in her school uniform watching the boys exercise in the yard before class. When I turned to leave, a beautiful woman who was seated on the curb asked me to take her picture. And down the block the story continued.

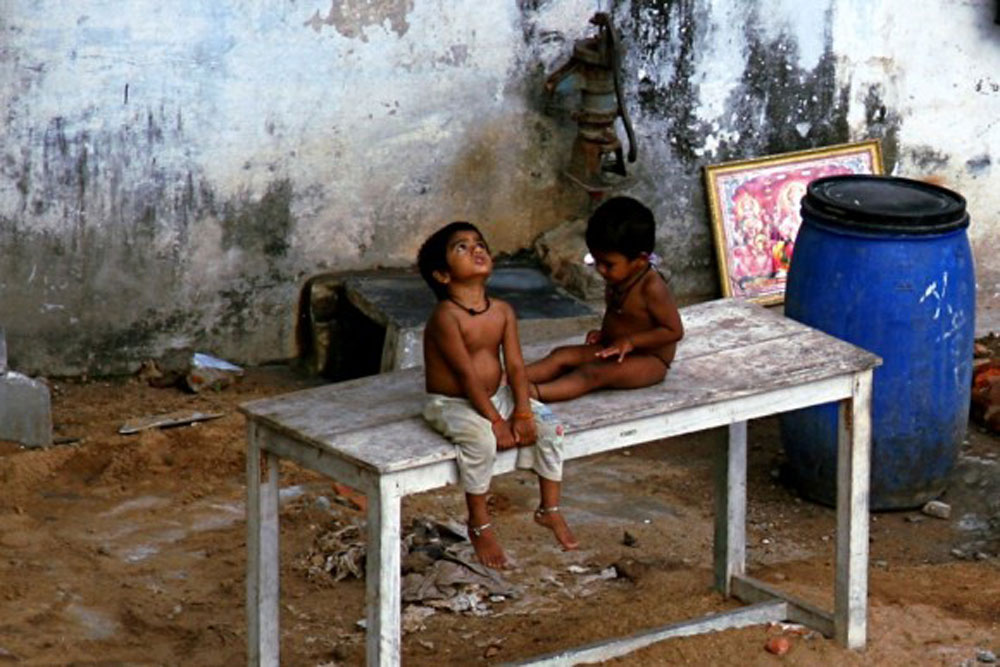

But the intrigue that strangers feel for us is both a blessing and a curse. One afternoon we walked from our apartment to the beach. Along the way we met a homeless family, and we made small talk. They were thrilled when we wanted to take their photo, and excitedly handed Sheena their bare-bottomed baby for the occasion. Arriving at the beach, we walked a hundred meters across the sand where mobile popcorn stands were painstakingly dragged through the deep sand, young Muslim and Hindu couples strolled, and people huddled in the shade of the dozens of abandoned wooden carts dotting the sand.

As we strolled, young groups of boys began approaching us. They would ask us where we were from, and then quickly ask for our photo. They had no interest in me; the bottom line was that they wanted their photo taken with Sheena. At first this confused us, but we were later told that they simply want to take photos of themselves with white girls so that they can post them on Facebook and claim that they have a white girlfriend. Now if anyone wants a photo, they get both of us or neither. This may seem like a small annoyance at first, but once we reached the waterfront we couldn’t walk more than twenty feet without being stopped by a different group of boys wanting photos with their new American BFFs.

After becoming quickly overwhelmed, we retreated toward the street. In doing do, we found ourselves behind a bunch of abandoned shacks, and soon a dodgy looking man fell in step behind us. We could tell he was behind us, but thought nothing of it at first. After a while we passed a trash pile, and the man bent over and picked up an empty glass bottle. He fell back in step and got really close to us and we could feel him burning holes in the back of our heads with his eyes. Sheena stopped and turned to me.

“I’m feeling uncomfortable,” she said.

“Got it, let’s go,” I said. We turned around and walked past the man with the bottle. As we passed him he got angry and threw the bottle at a shack and it burst into pieces. We speed walked out of there and made our way back to our hotel feeling a little exhausted, and a little jaded.

What can be said so far about India? It’s too loud, too stinky, there are too many beggars and touts, the traffic looks to be the worst we’ve ever encountered, and some of its people have a tendency to be inappropriate. But on the other hand, it’s possibly the most interesting place we’ve been, everybody is a intriguing to look at, and some of its people can be very kind. This is going to be an interesting place, if not more than a little overwhelming.