Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in Overland Journal’s Winter 2022 Issue.

At a crossing in the wild country of the Limpopo River may be found Gatvanolfant, the elephants’ hole. Here is also Oerwoud Store with the Wiltshire, a pub established in past times by a British Army unit that once guarded the drift across the river between South Africa and Botswana. This human watering hole was known for its cold beer and cheap whiskey.

Botswana is a sparsely populated semi-desert country, once a British Protectorate, and until recently, had a poorly developed road system, with properly tarred surfaced roads only found in the major centres of Gaborone and Francistown. The rest of the country was served by rough dirt roads or tracks through soft sand. As a result, pickups and trucks with oversize tyres, especially on the rear driving wheels, and four-wheel drives such as Land Rovers, Ford F-250s, Land Cruisers, and Bedford trucks were common.

A popular topic of conversation at the Wiltshire revolved around the best vehicle for use in the wild bush of Botswana. Herman, an adventure safari operator, used Internationals, unbreakable trucks they were. He cared nothing for Land Rovers as they broke axles. Len remarked that the Jeep was a fine vehicle. He had used them in the South African Army. They were indestructible vehicles and could go anywhere. He would like to get one. Johan remarked that his father had a Jeep on his farm near Machadodorp, a town on South Africa’s eastern border with Mozambique. He wanted to sell the vehicle because the rear axle was making noises.

So Len made plans. These involved a friend by the name of Broz, who was building up a Jeep and had a stock of scrap Jeep bits and pieces, including a rear axle. And so it was that one Saturday morning, Len and Broz headed to Machadodorp. At the time, both were students at university, neither had cars, and Broz’s father flatly refused to lend them his Mercedes-Benz for the journey, especially as they intended to load a spare axle in the trunk. They had no option but to hitchhike the 200 miles or more, toting the axle between them—and everyone knows the weight of a Dana 41, even without the springs attached. The less said about hitchhiking with a Jeep rear axle, the better. Kindly people in sedan cars would stop to give them a lift, only to take off at the appearance of the axle. Thanks to farmers with pickup trucks, they got to the farm many hours later.

The Jeep was found to be a CJ-3B of about 1956 vintage. The instrument panel still sported individual instruments; an ammeter; oil, petrol, and temperature gauges; and a speedometer. The inner windscreen frame could be opened up, and the wiper motors were vacuum operated. The canvas upholstered seats were tatty, and the tyres were worn 600 x 16 non-directional.

Squashing under the vehicle, Broz inspected the back axle and found nothing outwardly wrong with it; the oil was full, and there was almost no backlash nor sideways movement on the pinion. The axle was, in any case, a Dana 44, and such a mechanism is bulletproof.

The problem, however, was found to be with the transfer case. This was as devoid of oil as burnt toast, having all leaked out through the rear output shaft seal, the oiled-up handbrake drum evidence of this. An inspection through the rear cover showed beyond the intermediate gear having play on its shaft; there was obviously no life-threatening problem. Some hands full of grease were squashed into the transfer case, which was then filled with oil.

The farmer hospitably offered them accommodation for the night, and after early morning coffee, the Jeep was started with a pull from a tractor. Once warmed up, the engine ran as smoothly as could be expected from its somewhat worn YF carburettor; the oil pressure was adequate, and beyond a hint of blue smoke on acceleration, all seemed good to go. Concluding the deal, the farmer produced a bottle of murky liquid. “For you, take it to ensure safe travel, and have a sip before you go,” he said, uncorking the bottle, “a sluk (sip) to ensure a safe journey.” A hand-printed label declared the stuff to be Die Raat vir Elke Kwaal (the cure for every ill). The farmer explained such a sluk was a tradition passed down from the Boer War of 1899 when his great-grandfather fought the British. The stuff clearly worked as the British never caught Great-grandfather, and their journey back to Pretoria was quite straightforward.

The 3B was a wonder and had distinct advantages over earlier model Jeeps. Firstly, it was powered by the F-head motor, and although being hardly more than the excellent old L-head motor in disguise, it was in ways a better machine. The overhead inlet valve setup with 2-inch inlet valves and cross-flow design promoted much improved breathing with increased horsepower and torque. Furthermore, the cylinder head was not prone to warping and blowing gaskets as the old side valve flat head had been, and with better head cooling, exhaust valves no longer burned when they felt like it.

The other great benefits found on the CJ-3B were the Dana Spicer 44 rear axle and Dana 18 transfer case, now with an inch and a quarter intermediate gear shaft, infinitely more robust than the shaft used on earlier models. To make the whole contraption more attractive, the 3B had a stronger chassis than the MB or CJ-2A, more leg room, and a slightly higher windscreen for lanky types.

Back in Pretoria, Len sorted out all that was wrong with his Jeep. He replaced the intermediate gear and shaft in the transfer case, overhauled the brakes, and replaced suspension bushes and tie-rod ends. Not liking the sombre grey, he painted the Jeep a grassy yellow—baby poop, said his friends. Len used the Jeep for years on geological field trips and for work in the bush, interspersed with diving expeditions on the Zululand Coast, on one occasion nearly rolling off the edge of a high dune because he lost concentration when his girlfriend distracted him. Then, needing money to get married, he sold the Jeep to Garner.

Garner was from Dundee, a town in the province of Natal about 200 miles south of where Len lived. As he was about to leave with his new acquisition, Len presented him with the bottle of Die Raat vir Elke Kwaal. “For you, my friend, a sluk. Take this bottle to watch over you, to promote luck and good fortune in all your doings with your Jeep,” he said, uncorking the bottle. Garner’s sluk was complemented by a cough and an enthusiastic, “Hoo boy.” It certainly was foul. It need not be said that Garner’s drive home was quite uneventful.

Garner was very proud of his acquisition, save the baby-poop-yellow color, so bowing to his British heritage, rebranded the 3B a royal blue, using ordinary household enamel applied by paintbrush. The Jeep looked grand when viewed from afar, especially as he had splashed out on a new Bestop canopy and a set of 700 x 16 Dunlop Universal tyres. The Jeep was wonderful and took him and his wife, Bev, on adventurous trips about the country, to the Zululand Coast, the Cape, and up the steep and treacherous Sani Pass into LeSotho.

Then in July 1976, Garner and Bev joined Broz, Issie, Mike, Ron, and Swarts on a three-week trip to explore Northern Botswana.

Botswana borders South Africa’s northern and northwestern boundaries. It’s a mainly dry country of some 230 thousand square miles of primarily sandy semi-desert scrub known as the Kgalagadi. The centre of the country is dominated by the Makgadikgadi, 7,000 square miles of salt pan. In the north, the Okavango River, which rises in southwest Angola, drains into the Kgalagadi, forming a huge inland delta, a wildlife paradise. It was into this world they were headed.

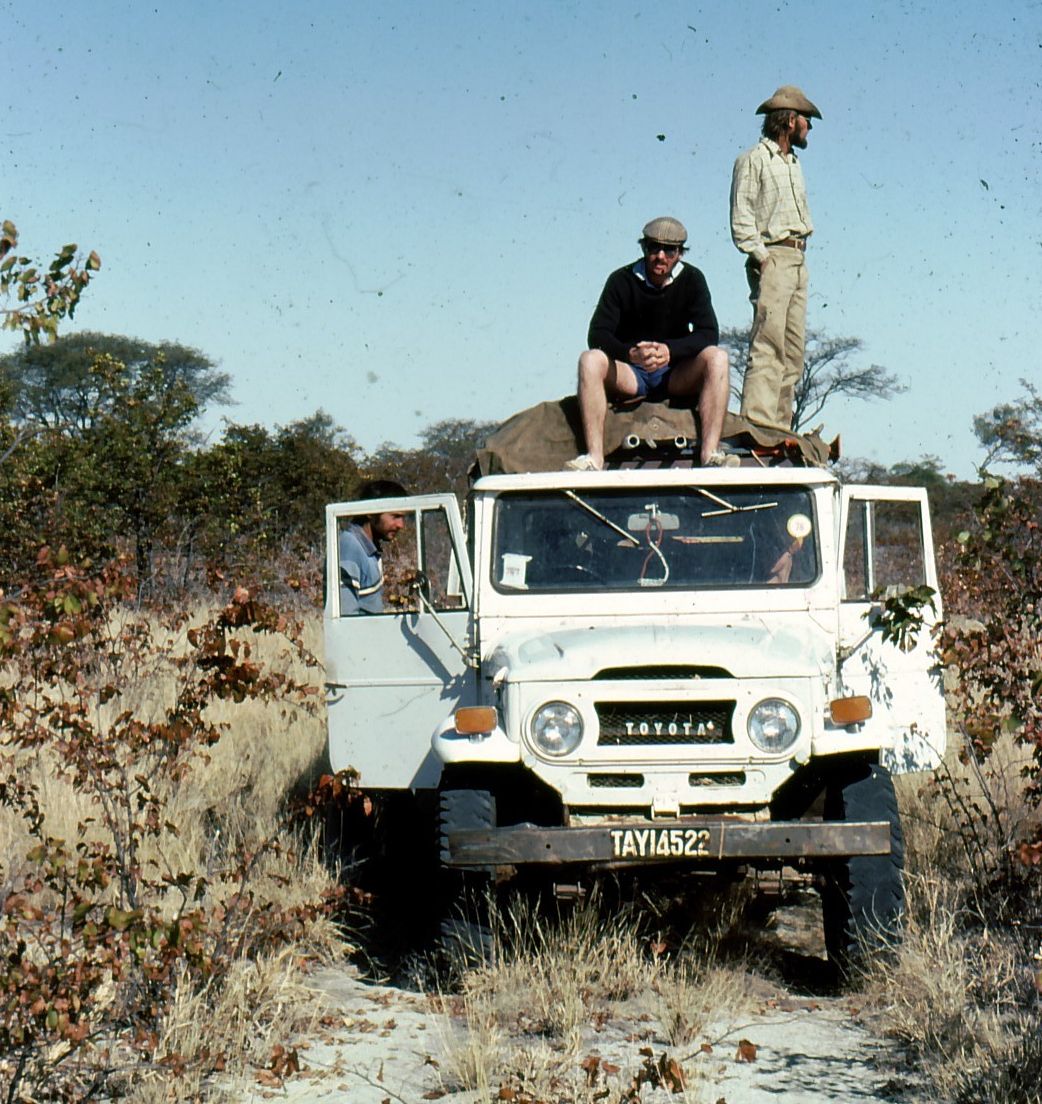

Broz had a Land Cruiser pickup, a 1972 FJ45, still with a three-speed transmission. Major towns were sometimes hundreds of miles apart on unsurfaced dirt roads, often involving days on tracks through soft sand where petrol consumption could drop below 10 mpg. The Jeep and Land Cruiser were well loaded with camping equipment, food, booze, cans of water, jerry cans of fuel, and necessary spares and tools. As they were about to leave home in South Africa, Garner produced the bottle of raat for all to take a sluk from to promote luck and good fortune in their endeavour.

Their route took them from Pretoria in the Province of the Transvaal Province west to the town of Gaborone in the southwest corner of Botswana—camp pitched at the town dam. It was the first night of their adventure, and they sat long into the dark hours at their fire, discussing their plans for the days ahead. The next morning they headed north the 70 miles of corrugated dirt road to the village of Mahalapye (pronounced Maghalapee), a stop made to rinse the dust from their throats at the bar of the Chase-me-Inn, where the stuffed head of a lion gazed at their doings. Jack Chase, the hotel proprietor, was most interested in their trip, being born in Botswana. He knew its every corner and suggested that instead of continuing on the stony potholed misery of the main road on to Francistown in the north, they head to the village of Serowe, taking the road passing President Seretse Khama’s house to follow a bush track west. After 65 or so miles, they would reach a junction with a track coming from the south, marked by an empty 44-gallon drum shot full of bullet holes. There, they should follow the track north another 60 miles before dropping down an escarpment onto the southeastern fringe of the great Makgadikgadi Pan. They should follow the edge of the pan to the village of Nata, about 70 more miles of dust and sand track north. At Nata, the Makgadikgadi Salt Pans bar served the coldest beer and meat pies the size of a miner’s boot. On the way, they should spend at least a full day on the northeast corner of the pan where the Nata River drained into the pan, a water wonderland and home to large numbers of flamingos, pelicans, and hosts of other waterfowl. Hearing of their plans to visit Moremi Game Reserve, he suggested they camp at the Xakanaxa Lagoon on the Khwai River. They were sure to see lots of elephants and many hippos. Lions could be a nuisance, though, so they should keep a fire going at night.

Garner passed the raat around again. They were now headed for the Kgalagadi, so a sip, a sluk for a smooth road in the desert wastes ahead. The road soon became little more than a sand track through thorny scrub. The 3B, undeterred by the deepest sand, moaned along in F-Head fashion, following the Land Cruiser. They stopped for the night in a wooded valley between rocky hills, grilled the local coarse sausage known as boerewors on an open fire of sticks and spent the night perfectly happy around the fire. Garner slept in a tent, maintaining it was the right and proper thing for a married man to do, the rest in sleeping bags or wrapped in blankets around the embers of the fire with the brightest stars overhead. Jackals yelped, and a lone hyena moaned in the dark.

The following morning, they took the sand track, winding through low scrub and bush, and then, voilà: the shot-up drum and intersection of tracks. That demanded a sip of raat for sure. Turning right, they followed the track north through never-ending miles of scrub and grassland before crossing the main road from Francistown to the Orapa Diamond Mine. Some miles more found them on the edge of the escarpment overlooking the southeast edge of the great Makgadikgadi Pan. It stretched to infinity.

A spectacular sunset saw them camped on the edge of the pan, revelling in the reflected light and open flatness of the place. Garner prided himself as a bush cook, making a stew of the last of their fresh meat. Not bothering about tents, they lay their sleeping bags and blankets on the white soda salt surface and slept, serenaded by the pirriping chirps of tiny scops owls in the dark.

After a sluk to start the day’s travels, they continued north on a track following the shoreline of the salt pan, the CJ-3B and Cruiser trailing plumes of white dust as they went. Ostriches and herds of springbok, wildebeest, hartebeest, and small groups of zebra galloped off as they passed. Later that afternoon, they found they were at the mouth of the Nata River, which during infrequent summer rain, emptied into the northeastern reaches of Sua Pan. They arrived as the sun touched the horizon and again marvelled at the dead, flat-white expanse ahead, toasted the sun’s going, and again slept under a sky of the brightest stars with geckos barking and nightjars calling and jackals again serenading the dark.

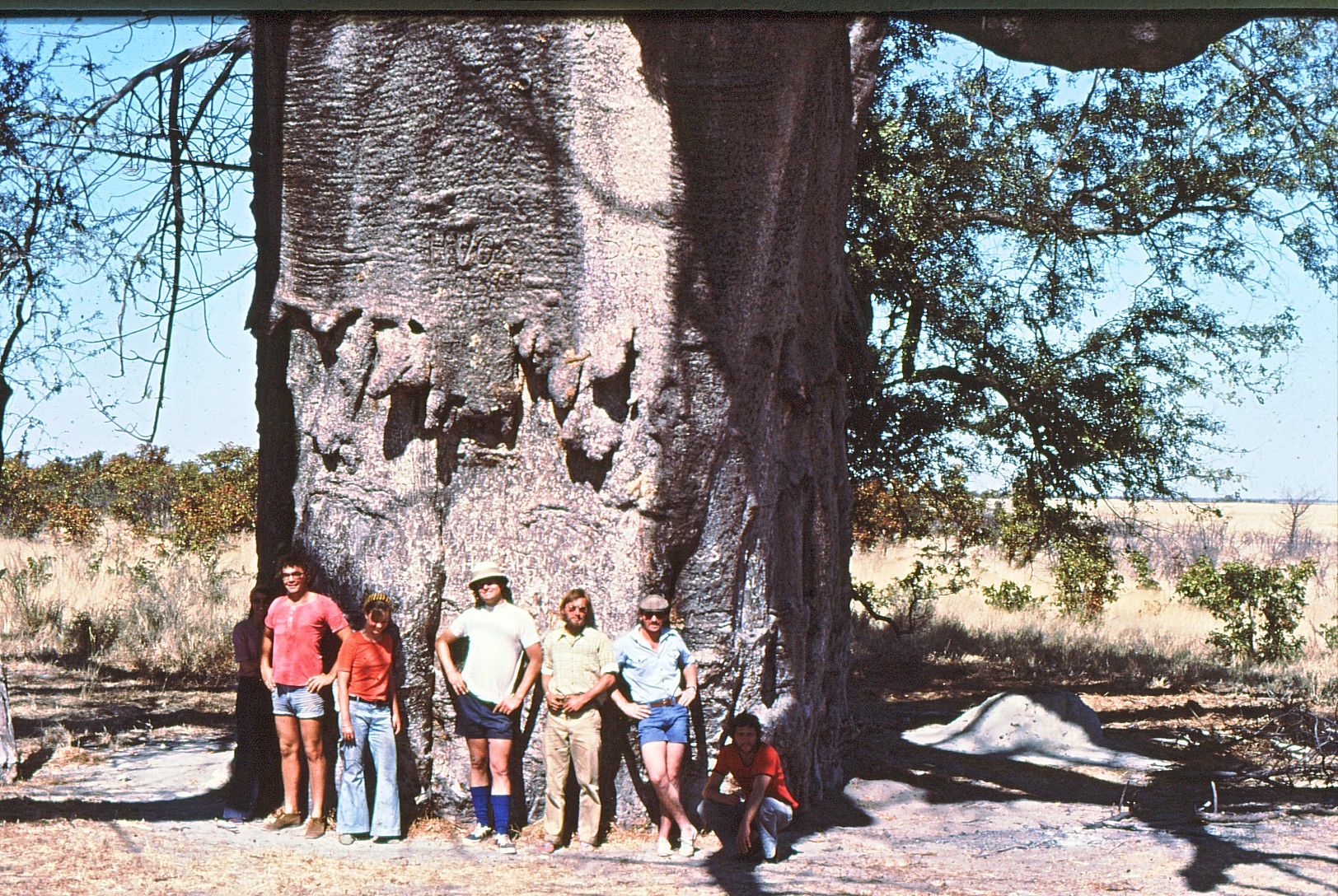

Flocks of different waterfowl, pelicans, and flamingos wading in the shallows held them spellbound over their early morning coffee. More herds of antelope sprang away at their passing as they made their way north to Nata, driving on the edge of the pan, the surface as hard and smooth as the best highway. Reaching the road, a gigantic baobab tree greeted them before they stopped at a foot and mouth disease control post at Dukwe Pan, encountering the first people they had seen for days. Thirty-five miles farther, they reached the tiny settlement of Nata, where the Makgadikgadi Salt Pans Bar did indeed serve the coldest beer and meat pies the size of a miner’s boot.

It was late afternoon when they arrived at Maun, the administrative centre for Northwest Botswana and then little more than a large village. Camp was made under great fig trees on the east bank of the Thamalakane River, a place of paradise after five days of dust and bush and no baths. Bailing out of their vehicles, they threw off clothes to leap into the clear waters of the river that drained the great desert delta of the Okavango River. Of crocodiles, they had no thought.

The next morning, they loaded up and took the 60 miles of sand track north to Moremi Game Reserve. A sluk of raat, ensuring safe travels in the wild country ahead of them.

Moremi Game Reserve is a most wonderful place, a world of forests of great trees, open grassland, shallow water pans, with the Khwai River meandering in channels, waterways, lagoons, and wetland swamps throughout the reserve. In those days, one could freely camp and walk where one would.

Entering the reserve at the South Gate, they bumped across Third Bridge, the much-photographed construction of poles across the Khwai River, and made camp on the lagoons at Xakanaka. Jack Chase’s words on the lions of the area rang in their ears, and so the Land Cruiser and Jeep were parked close by, and with a good fire, gave some measure of protection from the baleful dark. Being of the Realm of Real Men, they scoffed at tents and slept in the open with a sail to cover them from things that swished passed in the night. Still insisting it was the right and proper thing for a man with a wife to do, Garner set up his tent again to entertain his wife with snores. The others were not fooled, though. Lions loomed large in their imaginings, and a tent was a handy hideaway. But in the face of Garner’s nocturnal disturbance, the lions kept their distance and did no more than moan in the distant dark.

They stayed at Xakanaka for a week and had adventures with lion and aggressive elephant and buffalo, and saw huge herds of zebra and impala and giraffe and waterbuck and wildebeest and hartebeest and packs of wild dogs, and baboons and a leopard even, and more elephant than they ever wanted to see again in their lives. Garner was not sure about matters. Next to an overprotective elephant cow, his Jeep resembled a skateboard. He took a double dose of raat for insurance.

And then they split up. Garner and Bev wanted to see the Victoria Falls on the Zambesi River, 260 miles to the north, whilst the group in the Land Cruiser were dead set on exploring the wonderland of the Okavango Delta.

Leaving Moremi Game Reserve at the North Gate, Bev and Garner again crossed the Khwai River by yet another pole bridge and disappeared into the deep sand and bush of the Madikwe Sand Ridge and so on north for Savuti.

Savuti is an astonishing place where an arm of the Okavango Delta sometimes empties into an extensive grassland, which at times becomes a massive marsh and grassland of irresistible attraction to herds of every sort of game. The waters of the Savuti Channel swirled over the 3B’s bumper as they crossed and headed north for Kasane on the Chobe River close to that river’s confluence with the Zambesi River at Kazungula. The 3B was very small in all this, and they saw not another soul. There were lots of elephants, and they had to stop now and again to let them pass, waiting nervously with the engine idling as the great beasts milled around with raised trunks sniffing the intruder. Once Bev went to pee in some trees at the roadside and had just settled down when she noticed she was almost wetting an elephant’s foot. Garner gained courage by taking a few sluks of raat.

They camped at Serondella on the bluff overlooking the Chobe River, taking the ferry across the Zambesi River at Kazungula the next morning, from where it was but a short stretch of good road to Livingstone. They treated themselves to cold beer before crossing the Zambesi River on its great iron bridge to gaze in awe at the mighty waters thundering over the Victoria Falls into the chasm of the Zambesi Gorge, a sight they had long desired to see. After a meal and refreshments, they camped in the little town of Victoria Falls, their plan was to head south to cross back into Botswana at the little-known border crossing at Pandamatenga, to join the Land Cruiser group at Nxai Pan before returning to South Africa and home.

However, it was 1976, and Rhodesia was in the throes of a violent and bitter independence struggle. There was plenty of evidence of military activity about, with uniformed men and vehicles aplenty. At the time, civilian traffic on main routes was regularly ambushed by ZAPU and ZANU insurgents. Civilian traffic was conducted in convoys protected by armed soldiers.

In the meantime, the Land Cruiser group took a rickety boat called Slow But Sure, piloted by Mr Oscar Poesoetsile into the great swamp of the Okavango Delta, 120,000 square miles of wetland, the clearest waterways, islands, grassland, and beautiful forests. They camped on islands, poled along the channels aboard canoes carved out of a single log, and experienced great hospitality from people who provided grilled fish, boiled reed roots, and palm wine drunk from beautiful, tightly woven grass pots. They sat in small family settlements on islands and watched men making a mokoro while others carved paddles and women wove baskets.

Having enjoyed some of the wonders of the Okavango, the Land Cruiser group returned to Maun. After spending a night at their old campsite on the river, they headed east on the main road back toward Francistown to meet the Garners at Nxai Pan. Another 70 lonely dusty miles later, they were to take a faint sand track leading off to the north, marked by a Lucky Strike cigarette packet stuck on the thorn of a bush by the roadside. As luck would have it, they found the packet and took the track. Sandy, it was, requiring miles of low ratio first and second gear and four-wheel drive to cover the 20 miles to the pan.

The Nxai Pan area was another wonder. Covering 3,000 square miles, it is home to huge herds of springbuck, zebra, wildebeest, and giraffe. They saw families of suricates, a honey badger, locally known as a ratel, springhares, jackal trotting about, and both brown and spotted hyenas serenaded them with whoops and chortlings in the dark.

Expecting the Garners, they took the road, then but a little used track, for many miles northeast into the bush toward Pandamatenga, hoping to meet them with a welcome beer, but in vain. Of the Garners, there was no sign, the track undisturbed by recent motor traffic. As it was, life was not to be simple for the Garners.

Leaving Victoria Falls, the Garners drove on to Pandamatenga, only to find the border post closed because of the armed conflict in Rhodesia, transformed into a sand-bagged fort. They had no option but to retrace their steps. Without the benefit of joining a protected convoy, they headed on alone to the city of Bulawayo. Taking a good sluk of raat for luck and good fortune, they headed on. By late afternoon, they were still a long way from their destination and so cast about looking for a spot to camp. They found a likely place under beautiful trees on the bank of the Lupane River, a short distance from a great steel railway bridge that spanned the dry sand of the riverbed. They stopped and looked around at that peaceful place in the golden bush, so beautiful in the light of late afternoon.

.

.

Then Garner got a very strong feeling of evil, that they must leave the Lupane River, that this was not a good place to be, and that they were in great danger. So in fear and trepidation, they drove on into the night, for driving alone at night in Rhodesia at that time was a very bad idea. It was after midnight before they drove into Bulawayo and stopped at the public campsite. Great was their astonishment the next morning to see on television that the Lupane River Railway Bridge, where they had wanted to camp, had been blown up and destroyed by saboteurs during the night. That called for more consultation with the raat, much more indeed.

A while after this, Garner sold his CJ-3B: the little Jeep that had conveyed the Kaapmuiden farmer about his place before Len the geologist used it in all his scratchings in the hills, and Garner and Bev on other adventures on the Zululand Coast and up the tortuous steep Sani Pass into Lesotho. It was a grand car. He used the money to buy a Land Rover of all things because Bev produced daughters, and the little CJ-3B Jeep was much too small for all the accompanying impedimenta. At least it would take him on other great adventures, which it did, but that is another story.

Standing in pride of place on the mantelpiece of Garner’s home, next to some model Jeeps, is the well-used bottle with its tatty label declaring, Die Raat vir Elke kwaal. There are but a few drops left.

Our No Compromise Clause: We carefully screen all contributors to ensure they are independent and impartial. We never have and never will accept advertorial, and we do not allow advertising to influence our product or destination reviews.

Read more: Paradise Found by Roger Gaisford