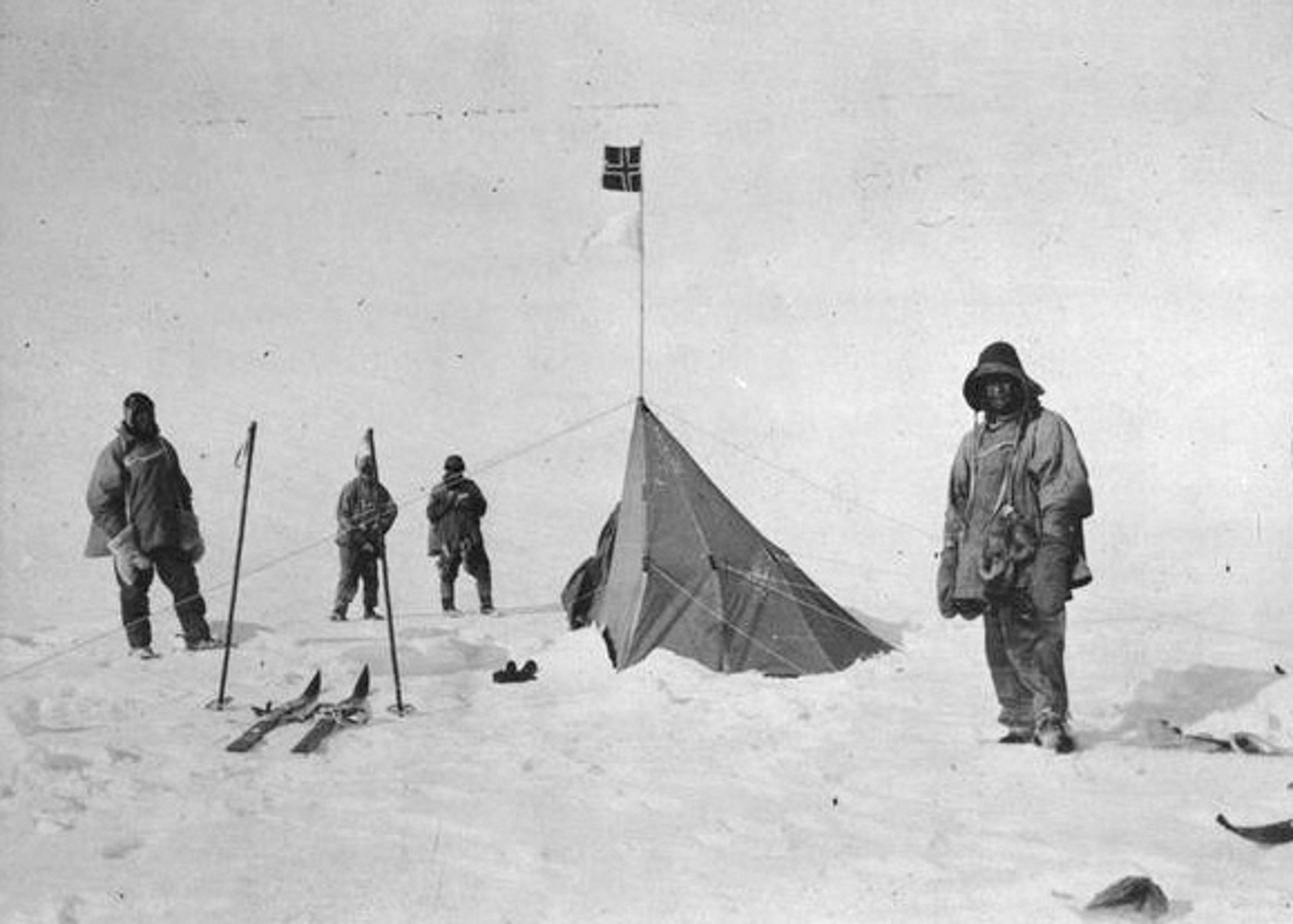

In 1912, only days after Robert Falcon Scott and his team of five explorers reached the South Pole, their fate took a doleful turn. Just 11 miles from the safety of their base camp, a fierce Antarctic storm forced them inside the cramped confines of a tiny canvas tent. The sullen conversation that ensued forecast their inevitable outcome. Lawrence Oates, suffering from debilitating fatigue and with frostbitten hands and feet, gave his now famous and moribund farewell. As he exited the sanctuary of the tent he announced to his comrades, “I am going outside and may be some time.” He never returned. The other four would eventually succumb to the ordeal as well.

Almost since the dawn of man, the portable abode has been an integral part of the human experience. An ever-present prop in countless scenes from history, it is more than just a safe haven. It has advanced our civilization, broadened our horizons, and allowed us to venture beyond the caves our troglodyte ancestors once favored.

It didn’t take long for early humans to understand what contemporary experts consider fundamental to survival: to stay alive one must have food, water, and shelter. Archaeologists generally agree the first structures to qualify as tents appeared in modern-day Moldova and date to the Upper Paleolithic era 40,000 years ago; they were constructed of animal skins draped over mammoth bones. A smaller number of researchers suggest the first tent is considerably older—another 360,000 years older to be precise.

Tucked inside the dark recesses of the Grotte du Lazaret, a cave located just beyond the cafés and promenades of Nice, France, archaeologists found what they believe is the outline of the earliest tent-like dwelling. Amidst thousands of prehistoric artifacts they found evidence of a wooden frame covered with animal skins held in place with heavy stones. Traces of grasses, furs, and seaweed suggest floor coverings used to insulate the occupants from the cold ground below. It even had a hearth and was divided into two separate living chambers.

For our ancient ancestors, mobility was essential to life. Meal opportunities often moved on four legs and frequently had to be pursued for long distances. Water and edible vegetation shifted with the passing seasons, and as the population grew, we were forced to disperse amongst our limited resources. The transportable habitat, a product of our migratory lifestyle, ushered in the age of nomadism that persisted for millennia. The Tuareg of the Sahara, Laplanders of Northern Europe, and the descendants of Genghis Khan on the Mongolian steppes are just a few wandering cultures living today much as they did centuries ago.

For North Americans, the tepee is the iconic domicile we have inextricably linked to the tribes of our great grasslands. Made of bison skins wrapped around a dozen or more lodge poles, the tepee of the Plains people could be erected quickly and comfortably house an entire family. It was a critical component in their endless chase of the vast herds that kept their societies alive. Although many believe it is exclusive to the Great Plains, it has been widely used throughout the world.

In the remote corners of Siberia and Russia, the Uralic tribespeople used a similar structure called a chum. Like their Native American contemporaries who followed bison, Europe’s northerners hunted migrating reindeer. The Sami of Scandinavia relied on conicalshaped tents called lavvus, kååvas, or kåtas. The Inuit, who occupied expansive ranges of land above the Arctic circle, built their pointed tupiks out of caribou and seal hides.

The Bedouins of the Sinai and Mesopotamia survived by trading goods and domesticating livestock, namely camels and sheep, which needed to be herded from one oasis and grazing area to the next. The silk and spice trading routes of antiquity were frequented by Romans, Turks, Persians, Somalis, Arabs, and Chinese. Each of these cultures utilized temporary shelters which permitted their extended journeys, many of which lasted for years.

Other nomadic societies throughout the world created their own moveable homes. Herodotus, the contemporary of Socrates and known as The Father of History, was amongst the first to mention the round yurts used by the Scythians in what is now Mongolia. Siberian Yupiks, pastoral Tibetans, and various peoples of Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, and surrounding regions still depend on the yurt to keep them protected from the harsh conditions of the Asian Steppe. First implemented more than 3,000 years ago, they are commonly constructed of felted yak wool panels stretched over a wooden lattice frame. For many people of Central Asia, it is core to their cultural identity. In Kyrgyzstan, the national flag depicts a stylized image of a tündük, or the rounded internal crown of a yurt.

As our civilizations developed beyond basic needs of subsistence, the tent, like many of humanity’s greatest technological innovations, was eventually pressed into military service. As the Roman Empire reached its zenith, the expansion of the realm became its raison d’être. Their massive army moved so quickly, fixed buildings could not be built fast enough to house the thousands of legionnaires on the march. Tents were required to keep tempo with their advances. A Roman encampment could be established in a matter of days and included a thousand shelters housing eight men each. Verona and Turin were initially Roman military encampments and exist today as modern cities. Throughout the annals of time, these temporary quarters have been integral to military exploits. From the age of Charlemagne to the American Civil War, the soft-sided dwelling has served millions of soldiers of every stratum.

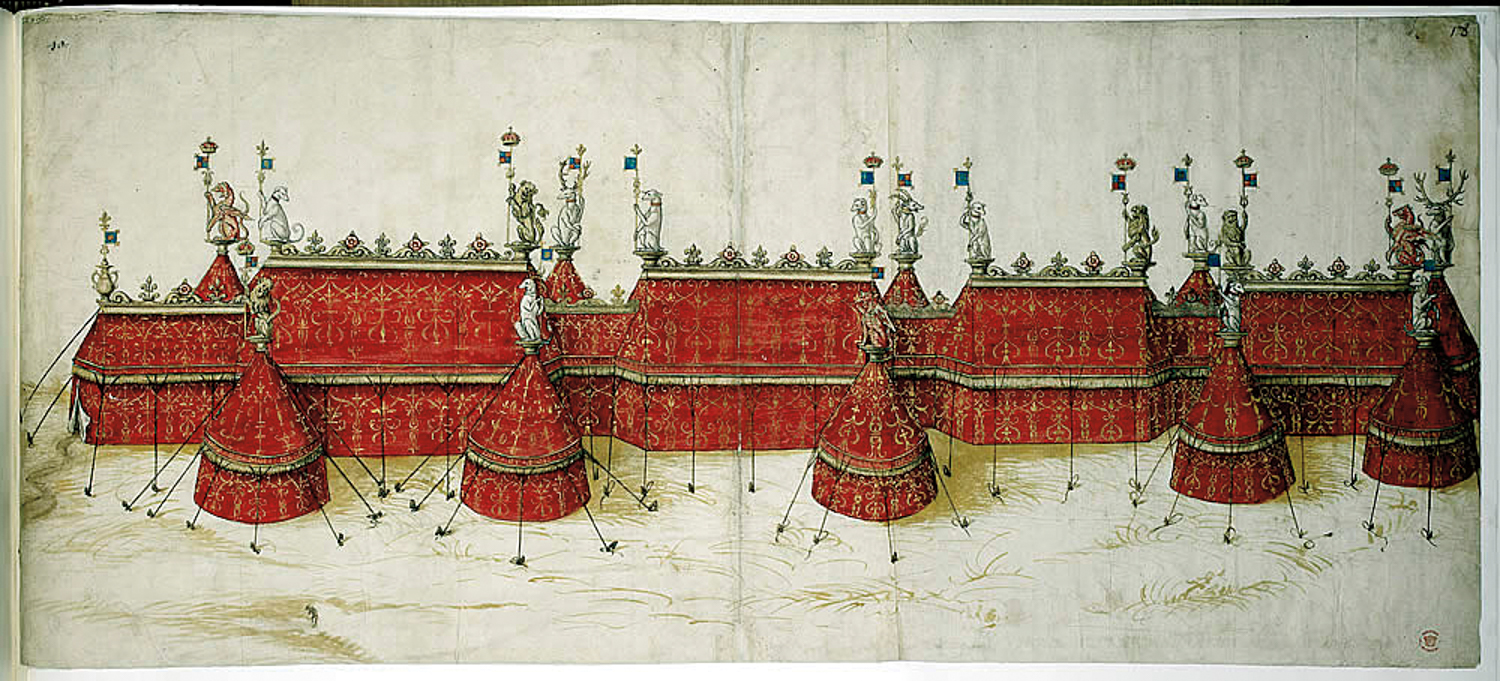

Beyond its martial applications, the tent was also leveraged to assert sovereignty and superiority. In the 15th through 18th centuries, during the height of the Ottoman Empire, they displayed the might of the ruling sultan. Throughout those years, great tent cities were erected utilizing immense and opulent structures designed to replicate the magnificence of the sultan’s walled kingdoms. Some featured fabric ramparts, battlements, and towering walls, analogous to those made of stone. French orientalist and archaeologist Antoine Galland, famed for his translation of The Thousand and One Nights (or The Arabian Nights), noted that sultans of the period oftentimes traveled with an encampment complex so lavish it had to be transported on as many as 600 camels.

At a time parallel to the dominance of the Ottomans, Mughal emperors in the desert regions of the Indian subcontinent also created palatial tents used for ceremonies, coronations, and assemblies with dignitaries to demonstrate their eminence. While traveling through Central Asia in the late 13th century, Marco Polo made mention of the extravagant tents that comprised the court of Kublai Khan.

As our wayward ancestors pushed beyond their familiar surroundings, the tent became an essential tool for exploration and the expansion of our known world. For the Norsemen of the 9th and 10th centuries, their shipbuilding skills allowed them to make strong shelters that could be transported on long boats. During the excavations of the Oseberg and Gokstad Viking ships, archaeologists uncovered elaborately carved wooden planks depicting Norse gods—frameworks that were to used to support heavy fabric tent panels.

In our modern era, the tent has continued to play a part in the discovery of distant lands. Lewis and Clark, John Wesley Powell, David Livingstone, and countless other dauntless explorers and adventurers relied heavily on their canvas homes as they plied uncharted rivers, crossed unknown lands, and mapped new headwaters. Sir Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay would have never reached the summit of Mount Everest without a means of overnighting on the high flanks of the peak. And Hiram Bingham’s 1911 discovery of Machu Picchu in Peru was only made possible due to their movable domiciles.

It would have also been impossible for Roald Amundsen to reach the South Pole, 34 days before Scott’s ill-fated team, without his canvas shelter. During that expedition in 1911, Amundsen pitched his tent as close as he could to the southernmost place in the world and dubbed it Polheim, or Home at the Pole. That tent, made by his longtime friend Dr. Frederick Cook, is reportedly still at that site. In 2012 a team of researchers located what they believe is the final resting place of Amundsen’s tent, but over the course of 8 decades of ice accumulation, it is estimated to be 56 feet below the surface.

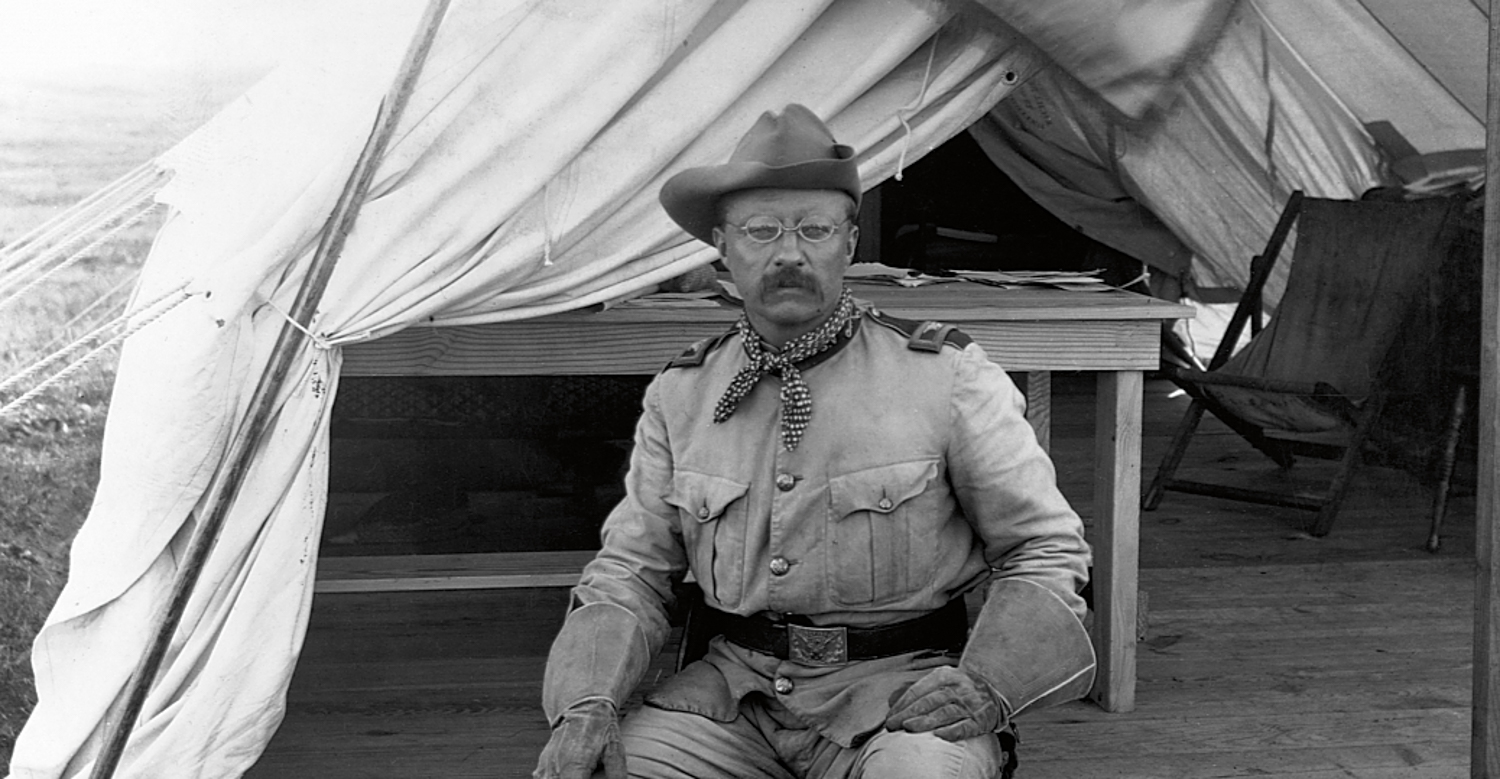

Some of the most intriguing narratives take place inside canvas walls. The harrowing tale of the Somali warriors who attacked Richard Francis Burton and John Hanning Speke mid-slumber during their African expedition is riveting. Teddy Roosevelt’s journal entries from his famous 1909 safari to Africa were invariably written at his campaign desk, set within his luxurious canvaswalled refuge. It must have been an extravagant accommodation compared to the cramped pup version he slept in while commanding his legendary Rough Riders during the Battle of Kettle Hill in the Spanish–American War.

As essential as it was to the age of exploration, and still is today, the tent remained virtually unchanged for thousands of years. Not until 1935, when DuPont scientist Wallace Carothers invented nylon, did these basic structures begin to evolve. With the introduction of aluminum poles and advanced architectural designs— like the geodesic dome made popular by R. Buckminster Fuller—the tent began to get lighter, stronger, and more portable.

Today tents employ space-age materials like high modulus carbon fiber poles, silicone-coated ripstop nylon, and anodized aluminum. A few, like those from NEMO Equipment, forego poles entirely in lieu of inflatable support beams made of 4-ply, diamond-weave sailcloth. Computer-aided designs have produced models that not only weigh a handful of pounds, but can withstand gale force winds and torrential rains.

We owe a great deal of our evolution as a species to the tent. Without it we never would have ventured beyond the safety of our subterranean hideouts. The next time you stop for the night to pitch your humble home away from home, take a minute to think of the Lakota of America’s Great Plains, Tuareg, and Mongols. Think of the spice traders, sultans, and Roman legionnaires on campaign to expand the empire. Imagine what it was like to watch Lawrence Oates slip out of the narrow canvas opening and into the endless white of an Antarctic storm. Where would we be without the tent? Stuck at home, that’s where.