Words By Chris O’Neill, Photography by Greg Fitzgerald

Here’s the thing about being in your favorite place in the world when it’s 5:00 a.m., 20°F, and there are 8 inches of snow on the ground—it’s still your favorite place in the world.

For me, that place is the Colorado Plateau, and I was there with my friend Greg, who I’d picked up in a 2021 Ram 1500 TRX at Salt Lake City International Airport the day before. We immediately headed south, fleeing the concrete and asphalt confines of civilization for Southern Utah and Northern Arizona, where we’d put this new 702 horsepower truck through its paces in the red rock desert over the next three days.

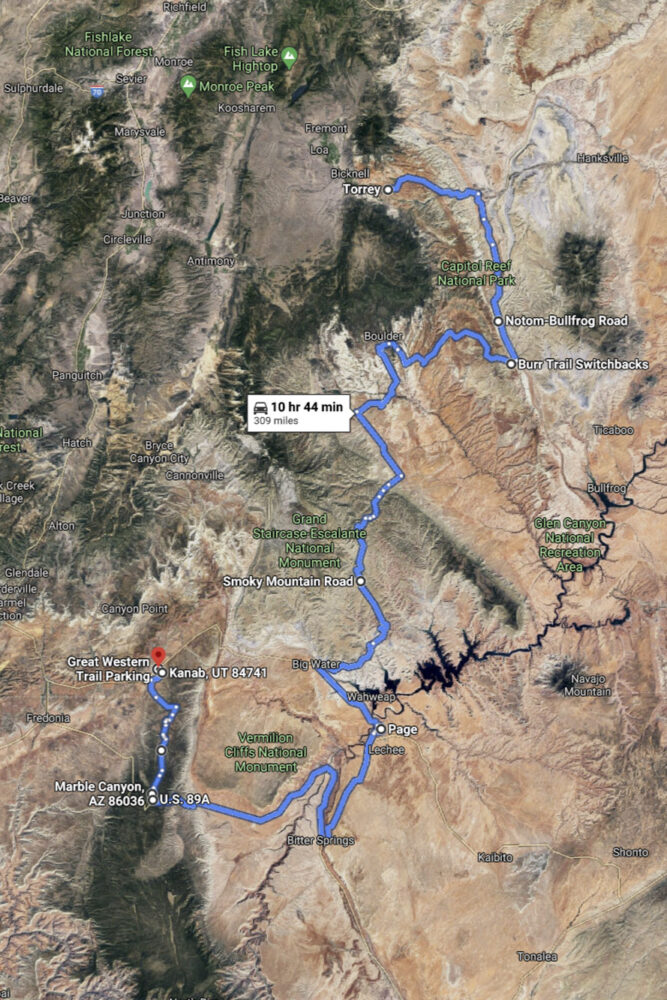

The Route

Our original plan was to leave asphalt via the north district of Capitol Reef National Park, known as Cathedral Valley, but a rare Southern Utah snowstorm the weekend before had placed much of our planned route under 8 inches of snow. The truck had a snow mode, a really good one, as we’d learn later in the trip. But with nightfall looming, we opted to head farther south via asphalt and made our way into the park via the main entrance in Fruita.

Capitol Reef was established as a national monument by Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1937 and existed that way until 1971 when it was named the country’s 36th national park. This coincided with a massive expansion that increased its size from just under 38,000 acres to 254,000. Until a few years ago, you could clearly see on the park sign where the letters M-O-N-U-M-E-N-T had been removed and replaced with P-A-R-K.

The southern district of Capitol Reef is primarily made up of a single landform, the Waterpocket Fold, a giant ripple in the earth’s crust running north to south through central Utah. With the last glimmer of daylight disappearing over the horizon on our first day, we ventured southbound along the frontcountry portion of Capitol Reef, bright orange sandstone cliffs to our left and rolling ivory domes off to the right. Dusk turned to darkness, and the asphalt eventually turned into a narrow dirt road. We took it all the way to its end at a trailhead, where we ate dinner in the dark off of the TRX’s tailgate, surrounded by 150-foot cliffs. The beast had largely been caged on our first day.

The Waterpocket Fold

After a night at the Days Inn in Torrey (pro tip: cheap hotels add texture), we started day two of our adventure at 5:00 a.m. in an effort to catch the sun rising over the Waterpocket Fold. We retraced our eastward tracks from the previous night, this time going a bit farther before turning off at Notom-Bullfrog Road, which follows the Fold down to Bullfrog Marina at the reservoir currently occupying Glen Canyon. The road runs through an area of Southern Utah I’ve looked down upon on numerous occasions from high up on Highway 12 as it passes over Boulder Mountain. From above, the terrain is an intricate smattering of whites, yellows, deep forest greens, burnt oranges, and reds. This morning, though, it was cast in darkness.

Notom-Bullfrog Road gave us our first opportunity to press into the TRX’s capabilities. While still being respectful of our surroundings, we were able to get to our turnoff point in about two-thirds of the amount of time it would’ve taken in a lesser truck or SUV. This isn’t because we blitzed through areas where a more conservative pace would’ve been appropriate, but rather because we were able to sustain our pace in turns, over washboard, and through rougher areas where you would’ve wanted to slow down to a crawl in your 4Runner or Wrangler. In those vehicles, you get to your destination, exhale, and say, “We made it.” In the TRX, you suddenly come upon your turn and say, “Oh, we’re already here.”

After a blue-hour photoshoot at our turnout, we ventured up the Burr Trail Switchbacks and hiked up to the Strike Valley Overlook, which lets you gaze across the valley at the Waterpocket Fold in its entirety. I’ve got a thing for landforms that can easily be identified on a map, and the Waterpocket Fold is one of them.

On our way into the town of Boulder, I played with the TRX in my favorite off-road setting, Baja mode. This is effectively Sport mode, but for dirt, and it keeps the revs high, the steering tight, and the suspension firm. Unlike in the Ford F-150 Raptor, you can’t put the TRX into two-wheel drive; it defaults to a four-wheel-drive auto mode, but I was still able to kick the back end out around turns as we carved our way over the dense hardpack that makes up much of the Burr Trail.

Kaiparowits Plateau

After passing through Boulder and traversing 28 miles of the winding, twisting two-lane road that is Highway 12, we rolled into the town of Escalante. You might not expect much from the small towns in rural Utah, but between Boulder and Escalante, there’s something for everyone along Highway 12. You can find a soda and chips at a gas station or burgers at some roadside stand, sure, but are you perhaps in the mood for some more bourgeois provisions? Maybe a farm-to-table dinner at a Zagat-rated, James Beard-recognized restaurant? How about a coffee on the side of a cliff? Cocktails? Emergency backpacking gear or some local art? You’ll find it, unexpectedly, along Highway 12.

Unfortunately for us, most of these places were still closed for the winter as we passed through, thus limiting our options when it came to commerce. We managed to find sustenance at a little

’50s-style place called Nemo’s, named for the preferred alias and sandstone tag of Everett Ruess, a 20-year-old vagabond who went missing down nearby Hole in the Rock Road back in the 1920s and has since achieved cult status.

Talking with some locals, we planned our next move. Knowing that we wanted to be in Page by sundown, we charted a course over the massive Kaiparowits plateau, which looms heavy to the south of town through the heart of the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument. Our route would be along Smoky Mountain Road, which we were told was the least likely to have considerable snowpack out of any of our options.

This portion of our trip wound up being the most arduous. We wouldn’t see asphalt for another 60 miles, which took us about 2.5 hours to cover. The route was hardly picturesque, consisting of the same dense evergreen scenery for about 45 of those 60 miles. We didn’t encounter one other vehicle along the way. The terrain was dense and rocky, the kind that wears out your neck and shoulders after just a few miles, even in a vehicle as cushy as the TRX.

As we made our way over the Kaiparowits, we found ourselves spending a lot of time fiddling with the TRX’s different drive modes, of which there are many. The issue that we were running into is that even in my preferred option, Baja mode, the transmission wouldn’t hold onto a gear long enough for us to climb an obstacle, the inevitable upshift contributing to the aforementioned maddening shifts in momentum. You’d think Rock mode would’ve solved the problem, but that requires the vehicle to be in low-range, and the distances between obstacles meant we wanted to stay in four-high. Greg figured out a custom setting that ended up working surprisingly well; we put the steering in Rock mode, which made it looser, the suspension in Baja mode, which averages out the bumps, and the transmission in Tow mode, of all things. Tricking the 8-speed automatic into thinking it was pulling a load meant it held onto gears longer, thus giving us more of the rev range to play with while navigating the flowy, rocky road.

Finally, the road straightened out, giving us the opportunity to sail along in our beloved Baja mode the rest of the way down to Page. There were plenty of dips and rollers through this portion, but only once did the truck’s tires leave the ground. I’ve jumped these trucks before, and while it’s fun, what isn’t fun is misjudging a landing and plowing the nose of a 6,400-pound pickup straight into the ground 20 miles from civilization. So we played it safe.

Toward the end, Smoky Mountain Road went from pinyon and juniper forest to a smattering of beige cliffs and castle-like buttes. The shelf road and switchbacks were a nice change of pace after a long day of tedious throttle modulation. We were off to Page for Mexican food, showers, and an evening spent plotting our next move at a newly constructed Hampton Inn.

Horseshoe Bend

We were up early again the next morning, this time with a plan to photograph the famous Horseshoe Bend. This has been done once or twice already, as evidenced by the hundreds of thousands of photos of Horseshoe Bend hanging up in stuffy art galleries in ski towns across the world. Upon making our way through the hordes of influencers to get to the overlook, though, we realized something: it’s hours before the sun actually hits the bottom of Marble Canyon, meaning that until the late morning, the Bend stays cloaked in shadow. No matter the light, though, there’s still an element of wonder to the clear water and glassy surface of the Colorado as it snakes around the sandstone. Camped on the riverbank was a group of campers who’d piloted a boat upstream from Lee’s Ferry, the glow from their fire a tiny indicator of scale from our position up on the ledge.

The Arizona Strip

After bailing on Horseshoe Bend, we were off to the Arizona Strip. This is the northwest corner of Arizona that’s largely cut off from the rest of the state by the Grand Canyon. At the eleventh hour the night before, Greg had remembered a guidebook he had at home that gave turn by turn directions for the Great Western Trail, part of which bisects the Arizona Strip. It would give us a way back into Utah while also allowing us to maximize our off-road travel. After a quick call to a friend back east, Greg had the directions sent to his inbox, which we printed out in the business center at the Hampton Inn. And just like that, we had our plan.

We headed south to Bitter Springs and then north again to take the Navajo Bridge over Marble Canyon. The original Navajo Bridge, built in 1929, is still standing, though a new bridge, completed in 1995, runs parallel to the south and is the one currently used for vehicles. Here we stopped to watch rafters float down the Colorado from Lees Ferry, which lies six miles to the north. A cold time of the year for a river trip, for sure.

Pushing farther westward on US-89A, we traced the perimeter of Vermillion Cliffs National Monument before arriving at Jacob Lake, where we’d gas up for the third time. The entry point for the Great Western Trail lay in an unassuming area off the side of the road. No sign, no markings—without our stapled stack of papers to serve as our pseudo-guidebook, we never even would’ve known it was there. We surged through a snowbank and onto what I assume was a dirt road obscured by 8 inches of fresh snow. The last leg of our journey had begun.

Now, as owners of what you could call more sophisticated off-road vehicles (I’m on my second Land Cruiser, a 2008 model, while Greg owns three Land Rovers), we’d been seeing some major drawbacks to the TRX. First of all, one of its main reasons for existing is to be brash and loud, which doesn’t exactly endear you to the locals in the small, rural towns of Southern Utah and Northern Arizona. Second, at its core, the TRX is a basic Ram 1500 pickup designed for job sites and towing as much as recreational use. So, where my Land Cruiser has loads of features for off-road touring like double sun visors, a built-in refrigerator, and extra dust seals on its split rear tailgate, the TRX lacks this kind of clever ingenuity. Finally, this thing returned about 11 miles per gallon while it was in our possession. Don’t get me wrong, 702 horsepower is intoxicating. On the other hand, this degree of gross inefficiency is hardly necessary in this day and age, which is why we’re unlikely to see another generation of the supercharged 6.2-liter V8 in the TRX’s engine bay.

On top of that, while to its credit, the TRX can be relatively tame on the highway, when it comes time to accelerate, the truck tends to give you either not enough or way too much. You’re either not going fast enough, or the truck is throwing you back into your seat, supercharger whining at full RPM. The lack of a middle ground on-road grew a little tiresome. All this had combined to make for a truck that felt somewhat one-dimensional to this point.

But deep in the woods, plowing through as much as a foot of snow, on arguably the most remote leg of our journey, the TRX went from being a really expensive toy to being an asset. Flip it into Snow mode, keep the throttle halfway to the floor, and the steering wheel pointed in the right direction, and this thing will churn through anything. The best thing about Snow mode is that it holds gears while stifling the effects of the supercharger; there’s a much more linear power delivery in Snow mode than you experience in the truck’s default setting. While the 702 horsepower supercharged V8 felt like overkill before, all that power propelled us, effortlessly, through terrain that either of us probably would’ve turned away from in our own Land Cruisers and Land Rovers. Fully aired up, the 35-inch Goodyear Wrangler Territory all-terrain tires still floated over the snow, the extra diameter helping to keep the truck from getting bogged down. The truck’s size was never an issue either, even though excessive width is a common criticism of this new crop of high-performance off-road pickups.

Conclusion

We got to the end of the road, literally, as it met up with Highway 89 east of Kanab. All-in, we’d covered about 750 miles, more than 200 of which were off-road. As for the TRX, it’s expensive and loud, and incredibly inefficient, however, in the right environment, it allows for a significantly more unique and more immersive experience than any other vehicle. The truck’s tire size, powertrain, suspension, and drive modes combine to make a vehicle that, make no mistake, is certainly a talisman but also a tool.

Terrain that would’ve been impossible to traverse in a rental car, and at the very least, tedious in one’s own Wrangler or 4Runner (or Land Cruiser or Land Rover), amounts to a Sunday drive for the TRX. On every leg of the journey, we got to our next destination sooner, less frustrated, and less fatigued than we would have in any other type of vehicle. And when you’re able to conserve your energy on a trip like this, you can do more, see more, and go further. And that’s exactly what we did.

I’ve ventured to the Colorado Plateau dozens of times now, and many of the places we visited— Capitol Reef, Escalante, Page—I’d been to before. But each of those prior trips had been for the sake of doing something; camping, hiking, climbing. On the other hand, this trip had been more for the sole purpose of seeing it all, taking it in in a more sensory way than I ever had before (and yeah, also to take advantage of having the keys to a 702 horsepower truck for the weekend). The sometimes spirited but generally easygoing drive gave me a new appreciation for this place that I had already loved so much. Its canyons and foliage, color palette, rock formations, and rivers are nothing short of awe-inspiring. Our means of transportation was a noisy and boisterous creation of man, but one that was dwarfed and, in a way, humbled by the majesty of the geologic wonder that is the Colorado Plateau.