Photography by the Toledo-Lucas County Public Library and Public Domain

Face-to-face with a large lynx, Blanche Stuart Scott’s heart pounded as she gripped the Colt .32 in her hand. “How do you do?” she asked politely, meeting the wildcat’s hazel-colored eyes. She and journalist Gertrude Phillips were amid a vehicle recovery on the way to Lake Tahoe, using block and tackle to continue up the steep grade. Slowly stepping backward, with her attention on the cat, Blanche murmured how friendly and beautiful he was, hoping that playing to the lynx’s ego would keep her safe. Finally reaching the car, she jumped into the driver’s seat of the Willys, revved the engine, and continued up the hill and toward San Francisco. Nothing would stop her from becoming the first woman to drive west across America.

Scott’s need for speed developed at an early age, during her childhood in Rochester, New York, just before the turn of the 20th century. After clinching several ice-skating medals, she turned to trick bike riding and, as a result (and to the dismay of her father), smashed up seven bicycles in the process. Vowing he would never buy her another bike again, Blanche’s father gifted her a Cadillac, which she sped through the streets of Rochester so frequently the local city council called a special meeting to discuss the wild, 5-foot-one, red-haired 13 year old that had taken to the streets.

After graduating from boarding school in New England (which I imagine was a struggle based on Blanche’s need for self-autonomy), she moved to New York City and worked selling cars. Automobiles hadn’t reached mass popularity by this time, and few women held jobs outside the home. Discovering that most women knew nothing about driving and maintaining a vehicle, Blanche sent a letter to the Willys Overland Motor Company, pitching a transcontinental trip. The official purpose of the journey, according to author Julie Cummins in Tomboy of the Air: Daredevil Pilot Blanche Stuart Scott, was “to interest women in the value of motor car driving, provide wonderful educational possibilities attending such a trip across the continent, and to promote the benefits of long-distance touring from a health standpoint.”

Willys, delighted to benefit from the publicity, jumped on board, and Blanche arrived at the New York City Hall ready for departure on May 16, 1910. Named “Miss Overland,” the Model 38 was a 25-horsepower rear-wheel drive car powered by a two-speed transmission. The slogan “Overland in an Overland” was painted on the engine cover, while blocky letters behind the driver’s seat read “The Car, The Girl, and the Wide, Wide World—New York to San Francisco.” Willys described the $1,095 Overland vehicle as “so simple and trouble proof that even a novice can successfully operate it from the very start. All complex mechanisms have been eliminated in this car. It is the ideal women’s car.”

Thousands of people lined Fifth Avenue to witness Scott’s departure. Accompanied by Journalist Amy Phillips, who would document the trip, Scott accepted a bottle of Atlantic Ocean water from Mayor William J. Gaynor, who officiated the event. Admiring the Overland’s 32- x 3.5-inch Goodyear tires (including two spares) and accessories, additional water bottles, five-gallon gas and oil cans, acetylene lamps for night driving, and a cylinder of compressed air in case of a flat tire, spectators gathered to witness history as Scott climbed into the driver’s seat. The rear seat was replaced with a large wooden box, which housed Blanche’s clothing, tools, and spare parts. She started up the 4-cylinder L-head engine, fitted with a single Schebler carburetor, and watched as a crowd of photographers elbowed to get the perfect shot.

Scott told the New York Times there would be “nothing spectacular, strenuous, or notorious in the performance,” which, according to the Times, she approached with a “most beautiful modesty.” However, hard spring rains at the outset made going tough—so much so that Amy Phillips packed it in after a week on the road. Going forward, Amy’s sister, Gertrude, took on the role of the traveling journalist. “You must realize that, those days, there were only 218 miles of paved roads, exclusive of cities in the U.S.,” Scott told the Democrat and Chronicle in 1946. “There weren’t even any road maps for certain parts of the country, where cowpaths along the old Union Pacific were the only roads.” On the pair’s most challenging day, they covered only 14 miles due to unmapped streams and river crossings.

Visiting all 175 Willys Overland agencies, Blanche and Gertrude wove 6,000 miles cross-country. Although the vehicle had a windscreen, the women were completely exposed to the elements otherwise. Early 1900s driving clothes did their best to protect from dust, mud, bugs, and weather in the form of duster coats worn over a tailored suit with a long A-line skirt, matching jacket, and separate high-cut blouse. The cherry on top was a very large driving bonnet, complete with ribbons, to protect the hair. You really have to see it to believe what was fashionable (although not very aerodynamic) at the turn of the 20th century.

The Detroit Public Library holds a decent collection of digital archive photographs from the cross-country tour, where Scott and Phillips are shown holding vacuum flasks while picnicking on the roadside. An escort car led the Lady Overland by about a mile, while rival car manufacturers sent out groups of male reporters for days at a time to cover the story. Although the media coverage was welcome, it added another complication to the journey: lack of privacy. During a drug store visit en route, Blanche purchased a stomach pump, which she inserted into a hole cut into the vehicle’s floorboard, effectively creating a portable “she-wee” device so she and Gertrude could drive all day without stopping. This caused great confusion among the reporters, who were told by Blanche that she and Gertrude had “cast-iron kidneys.”

After 10 weeks and 42 driving days, the pair arrived in San Francisco on July 23, 1910. Greeted by the mayor, a street parade, and a military band, Scott ceremoniously poured the Atlantic water into the San Francisco reservoir, mixing with the Pacific. She and Gertrude had covered 260 miles on the furthest driving day while Scott pushed the car to a top speed of 50 mph on a hard-packed lakebed in Nevada. But when she arrived in San Francisco, she didn’t yet realize that she was the second woman to drive coast to coast across America after Alice Ramsey, who set the record a year earlier in a 1909 Maxwell DA. Blanche had, however, made her own repairs—Ramsey had not.

“I discovered I was totally unsuited for the life of bridge, telephoning, socials and social visiting. The great big world was out there and there were things to be done that were more important than who trumped Charlie’s ace or who fell into the punch bowl Saturday at the Country Club. The interests of Dayton society were a million light years from mine, I couldn’t care less about bridging the gap.” – Blanche Stuart Scott

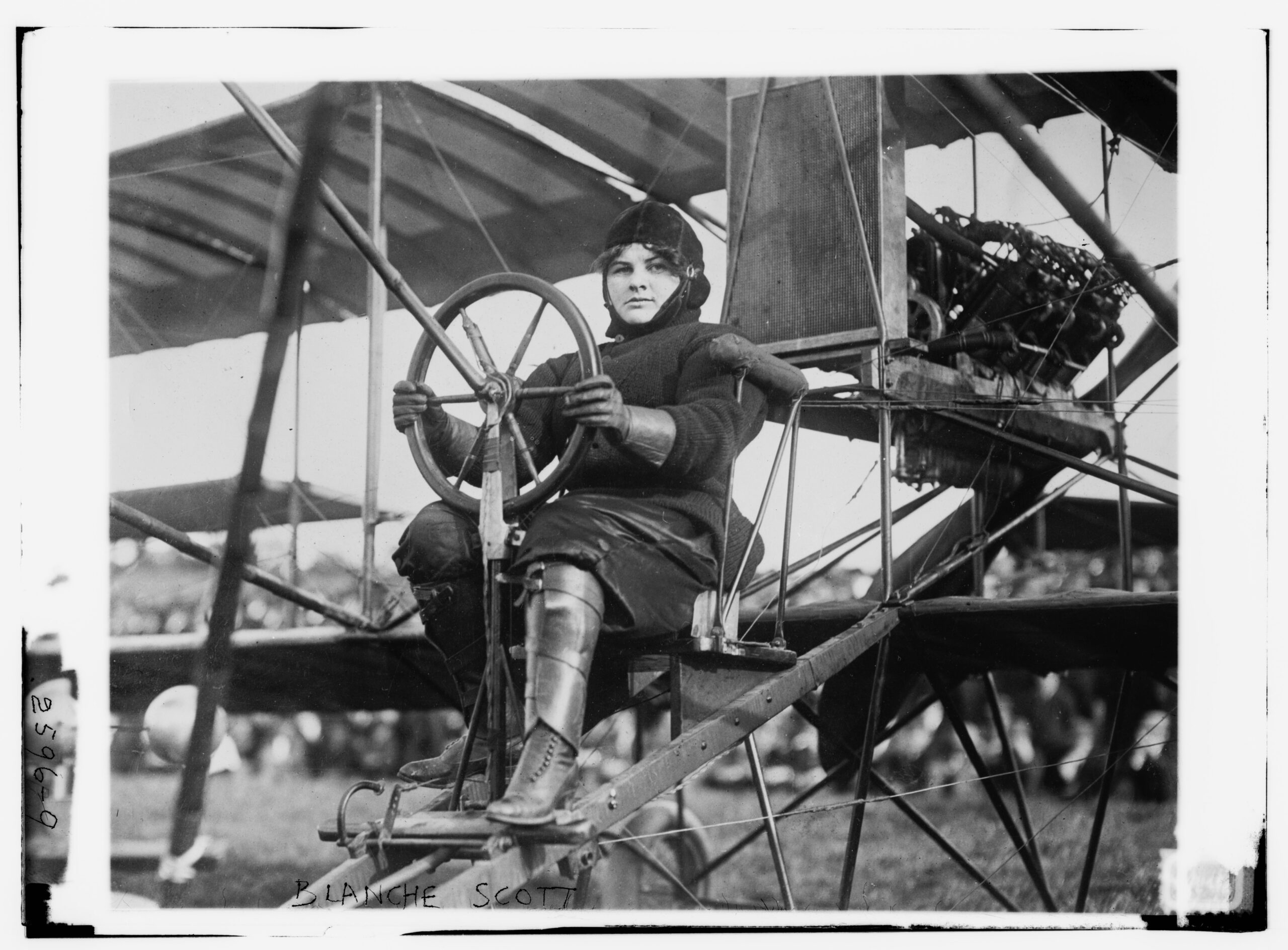

Life isn’t always about firsts, though—a journey such as this nearly always presents unplanned opportunities. As Scott approached Dayton, Ohio, during the cross-country tour, she and Gertrude were delayed by a crowd of ten thousand people who had gathered to watch a spectacle at the Wright brothers’ airfield. Put out by the delay, Blanche huffed that “anyone poking around in the clouds in a glorified kite had to be a nut… a complete and absolute idiot!” Months later, she signed a contract to join the Glenn Curtiss Flying Exhibition Company, eager to be the first woman to pilot an airplane in the United States. On September 2, 1910, in a field near Hammondsport, New York, she did just that.

Blanche became an exhibition pilot, setting multiple long-distance flying records and starring in the first aviation motion picture, The Aviator’s Bride. Despite the risk, and, as her flying reputation grew, the incidence of crank calls, hate letters, death threats, and overall sentiment that it was indecent for a woman to fly an airplane, she continued to perform for crowds, where she was hailed “The Premier Woman Aviator of the World.” “Each offer to fly was like a hot needle shoved into quivering flesh,” she said about her passion for aviation. “There was an inescapable thrill and exhilaration in flying and being in the air.”

Photo courtesy of the Bain News Service, publisher, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Although she retired from active flying in 1916, Scott’s accomplishments continued. On September 6, 1948, she became the first American woman to fly in a jet, and throughout the 1950s, she acted as a public relations consultant for the United States Air Force Museum, traveling around the country to collect early aviation artifacts. She died on January 12, 1970, but is remembered for paving the way for women drivers and aviators with a take-charge attitude. “Women should wake up and take a serious, intelligent, articulate, practical interest in what makes the world tick,” she told the New York Herald in 1911. She certainly led by example.

Our No Compromise Clause: We do not accept advertorial content or allow advertising to influence our coverage, and our contributors are guaranteed editorial independence. Overland International may earn a small commission from affiliate links included in this article. We appreciate your support.