Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in Overland Journal Magazine, and is available as a back issue here

The Hemi barked to life, squatting the rear of the Wrangler, accelerating us up the face of the dune. Dave did his best to navigate the aggressive camber of the slip face and the large bush that blocked the cleanest line to the top. The transmission hesitated, downshifting too late and causing the tires to break free from the available flotation. Instead of accelerating more, Dave backed off the throttle and came to a controlled stop. Even with 37-inch tires and a 400-horsepower V8, the soft silica was too much, and a different tack was required. Backing down would have been difficult, and the Jeep was already listing heavily to the driver’s side. It is moments like this where someone’s true experience shows through, the 10,000 hours that come to a practitioner of their craft. Gently, Dave rolled the vehicle rearward ever so slightly, bringing the tires to the rear lip of the small hole dug when the tires spun. He used that position to restart the climb, and we progressed another foot higher. Again, he backed off before the vehicle was grounded to the frame, and another attempt was made—the perfect balance of momentum and acceleration moving us forward a few feet. With one rock of the throttle, the Wrangler hooked up, and we started building momentum to the top, to the cheers of our teammates on the crest.

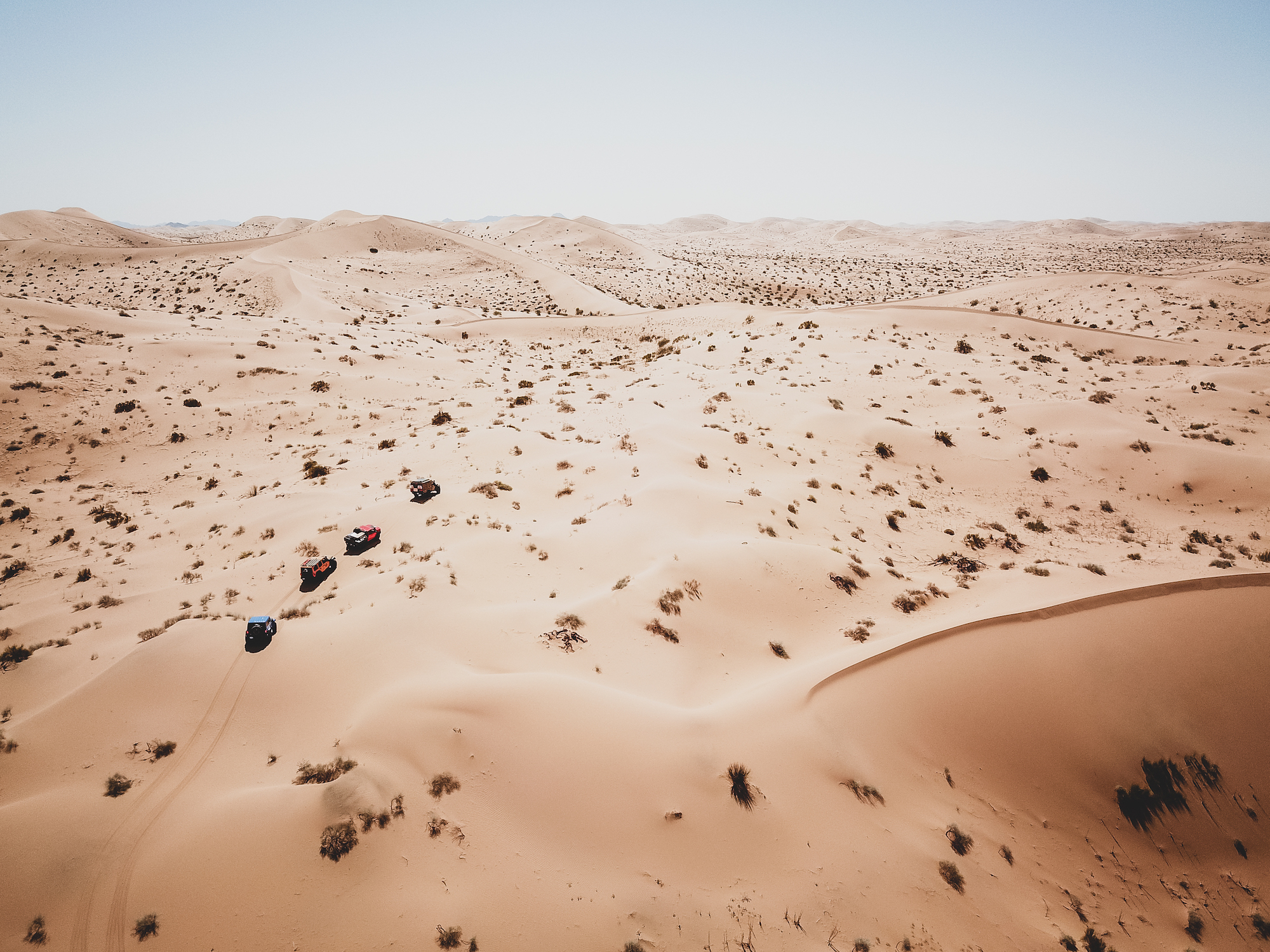

Nobody wants to read about what I ate for lunch—unless of course, it is tacos. The elements of a good story require far more than what a traveler had for breakfast, but the travelogue remains the most common means of sharing an adventure with a reader. As a result, there are times when an experience goes so (near) flawlessly that there is little to talk about. That is how our recent crossing of the Altar Desert in Mexico went. Not a single breakdown, never lost, never stuck, and no one got hurt, sick, or even upset. Instead of describing how beautiful the sunset was (stunning), or how good the lobster burrito tasted in El Golfo de Santa Clara (amazing), I decided to share the story of what made everything go so well. The ingredients of a safe, memorable, and successful journey.

It was about -30° as we drove away from Tuktoyaktuk, Dave Harriton and I piloting his Ram tray back on 41-inch tires. We had just made it to the northernmost vehicle-accessible village in Canada and were grinning from the euphoria of having accomplished the goal and experiencing some of the most breathtaking scenery in North America. Yet, as one does once an objective has been met, we started planning the next one. This is how the idea of crossing the Gran Desierto de Altar was born.

It All Starts With an Idea

Almost any adventure is worthwhile, but what makes a particular trip so special? For me, it begins with a unique idea or a location with some rare or unusual attribute. In the case of the Altar Desert, it is the largest dune system and the only active erg region in all of North America, a feature that spans north and east of the Colorado River Delta. All of the sand in the dunes and sediment in the delta has come from the Colorado River, and the Grand Canyon it carved over eons. This area is significant to the overland traveler for many reasons, including the remoteness, technical challenge, research and skills required for route finding, and ultimately, its international location. This is not a place to drive into without a plan.

Having crossed the Altar for the first time in 2012, I was aware of the general route and limitations. One of the most critical considerations is the boundary of the biosphere reserve, which cannot be crossed legally. It is a vital protection area just east of 114 degrees longitude. It is only possible to drive west of that border, and additional care is needed to avoid private lands used for agriculture in the north. This is where Google Earth is magic; it allowed me to find a road into the sand, and to plot a generalized path through the largest of the dunes, while also staying out of closed or restricted areas. Connect with locals on what spots require additional permissions.

It is easy to follow the latest idea en vogue, or the most common route hashtagged on Instagram, though it is the path less traveled where the real gems can be found. Searching out new routes also reduces impact to those popular tracks, and reduces the likelihood of sharing a campsite with a half dozen others.

I still remember the first time that I drove a Jeep on 37-inch tires in technical terrain. It was a 5.7-liter Hemi Wrangler with 3.5 inches of lift and a catalog of accessories. It can best be described as effortless, as I traversed terrain with ease that my Land Rover would struggle greatly to cross. Massive ledges and rocks became a point and shoot affair. The same was true the first time I ascended a glacier in Iceland, the Arctic Trucks Prado with 44-inch tires, dual lockers, and dual transfer cases slowly fighting gravity at 2.5 psi. With the right equipment, the impossible becomes probable.

A Suitable Tool for the Job

One of the other elements of a successful journey is selecting the right vehicle and equipment for the adventure. This is not to say that most overland trips require some highly specialized machine and a dozen Pelican cases filled with exotic gear, but some environments do necessitate a level of capability and reliability. In the case of the Altar, the dunes are big, easily taxing the available flotation and performance of the average SUV or pickup. Even when we crossed the ergs in 2012, the Land Rovers were often stuck, and the learning curve was steep for the less- experienced drivers. However, for this trip, we used vehicles with extensive modifications, larger tires, and higher horsepower motors. The results were night and day, without a single vehicle requiring a winch or strap. This allowed for more time in camp and a more relaxed pace, although it did remove some of the fun of testing the limits of smaller tires and underpowered Rover V8s and diesels.

In contrast, the Jeeps and Chevrolets for this trip were equipped with significantly taller and wider tires, the smallest being a 35-inch Interco on the Colorado Bison. The Wranglers sported tires as large as 37 inches and benefited from higher horsepower V6s and 8-speed transmissions. The Wrangler JK Outpost enjoyed the bark of a Hemi V8. As a result, the drivers were able to attack taller dune faces with shorter runups, and even correct for a poor line choice or loss of momentum with a press of the accelerator. The suspensions were also significantly modified, complete with taller springs and custom-tuned shock absorbers.

Each of these vehicles was particularly well suited to the challenges of the sand, and the modifications were either premium OEM offerings (like the suspension on the Bison), or thoroughly engineered aftermarket enhancements from American Expedition Vehicles (AEV). It was also impressive to travel such technical terrain with a flatbed pickup loaded with over 100 gallons of extra fuel and water, along with a massive Yeti cooler and a pile of personal effects. The perfectly flat load floor was essentially a square and allowed for quick access to everything on the platform. Tie-downs were everywhere, and the sides would fold down, making the entire process even easier. The downside to this type of configuration is reduced security, but we were so remote that it didn’t matter. Overall, the Bison was a workhorse and sipped fuel with the small-displacement turbo-diesel.

The other surprise from the trip was taking a self-contained camper along for the crossing, the Outpost II. This machine is the brainchild of Dave Harriton, CEO and head designer for AEV. Dave is a longtime friend, and he wanted to see if a “house” on wheels could make the crossing. In the end, what made the Outpost work was the attention to detail, from the use of lightweight composites and minimalist design to the fitment of a 5.7-liter Hemi and 37-inch tires to help propel the camper through the dunes. Dave slept in total comfort, sealed off from the blowing sands.

For the rest of us, various degrees of success were experienced when sleeping in tents on the ergs. On the second night, the wind blew hard and pulled at the stakes in the soft ground. The stakes were better than the typical bent rods, a cross shape of extruded aluminum with more surface area, but not enough. Tent pegs pulled free, and one tent tumbled for several meters before being stopped by the side of a truck. We improvised and used the vehicles as windbreaks against the silica still pummeling the thin walls and mesh. Being three-season tents, the designs were all intended for increased airflow, which also allowed a steady cascade of sand to fall inside and collect on the sleeping bags and us. It was no fault of the tents we used, but this was a lesson learned for next time: either sleep inside the vehicles or bring four-season tents that can be fully sealed on the windward side (still allowing for some airflow on the leeward side).

There were a few other pieces of kit that worked like a charm, including the mess kitchen that Dave brought along. It is designed for whitewater rafting trips, so it was extremely robust and also collapsible. The entire unit was constructed primarily from aluminum and is well sealed from both water and dust. This made for a perfect gathering place at the end of the night and early morning to prepare meals and clean dishes. Dave would set it up next to the Outpost, which had a National Luna fridge on an exterior slideout—ice cream for everyone. He also used a semi-porous drop cloth to keep the entire area relatively clean and organized. I still remember how good the pancakes and bacon tasted deep in the Sonoran Desert

The most powerful takeaway I have experienced from my more ambitious overland adventures is the deep gratitude and respect for the individuals I have traveled with. Of any of the trips that went awry, it has always been attributed to the weakness in someone’s character. Just like any organization, we all require a healthy, motivated, competent, and optimistic team. This was never more apparent than during the Expeditions 7 crossing of Greenland, where I had the pleasure of crossing the world’s largest island with some of the most exceptional individuals of character I have experienced in my travels. Picking the right vehicle is easy. Coming up with a great idea for an adventure is even easier. But it is the company we keep during the trip that will make all the difference.

The Company We Keep

Certainly, inspired ideas and innovative equipment add to the success and pleasure of an overland excursion, but what matters most is the experience. That can even mean going it alone, and the care we show ourselves on a solo journey. For me, any adventure is made sweeter by having others to share it with—the laughs and memories that come from the challenges and wonders along the way. Because of this, it is important to be deliberate about who we have along. The positive attributes of someone will likely shine on an adventure, while the negative traits will be amplified by the uncertainties and difficulties of life on the road. Some people thrive in harsh conditions, while others wither and retreat. I have seen both happen in the field, and it can have a significant impact on the enjoyment of everyone involved. One of the best ways to ensure a good team is to understand everyone’s goals and expectations, a clear insight into what they hope to experience during the trip. If left undetermined, it can quickly lead to frustration and disappointment. For example, if one person loves to drive every day, and the other prefers to spend a few days in each location, a compromise needs to be identified early on. The secret is in the planning.

For this trip, I knew all but one of the travelers, and they were vouched for. In the case of Brian McVickers, Dave Harriton, and Chris Wood, I have known each of them well over a decade and have traveled extensively with them, too. They are all levelheaded and respectful, in addition to being game for nearly any challenge. Some are better at planning, and some at execution, but all are as dependable as the day is long. Frustrations will invariably arise on any trip, so the company we keep will make all the difference when things go sideways. I remember the night when the sand blew so hard that our staked tents buckled and our sleeping bags filled with silica. There was not a single grumble from the group, and the hardship was addressed with self-deprecating humor and optimism. Egos had been checked at the border, and we all worked to make the trip a success for everyone.

During our travels, we often discover limits. We encounter the fringes of our character and the capability of our equipment. The assumption is that buying more things will make it better, that going from 33-inch tires to 35-inch tires will somehow enhance the experience. It won’t, and neither will another electronic gadget or pair of synthetic underwear. Overland travel has foundational principles for genuine adventure, and that comes down to visiting a place we are excited to see, bringing a vehicle and equipment suitable to the task, and being very, very intentional about the company we keep. After that, it is all about the journey.

Expanded Gallery of the Altar Crossing:

DCIM100MEDIADJI_0105.JPG

DCIM100MEDIADJI_0128.JPG

DCIM100MEDIADJI_0155.JPG

DCIM100MEDIADJI_0184.JPG