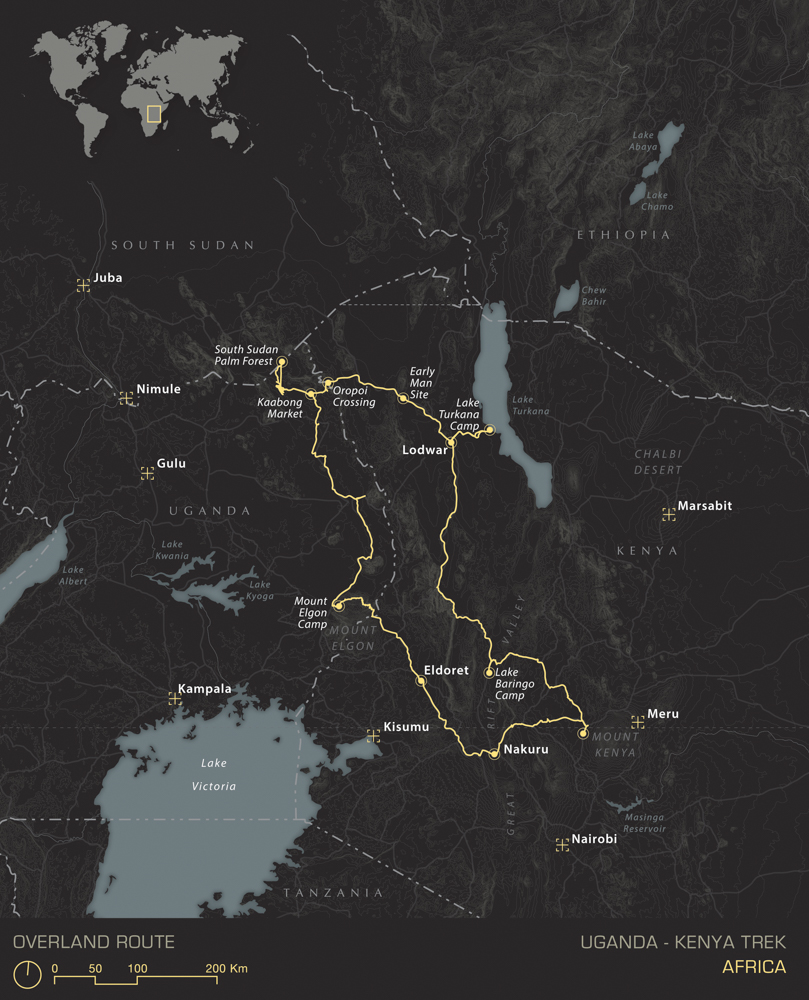

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in Overland Journal, Spring 2017.

Kenya stretched out before us. We moved slowly and deliberately along a rogue track through the rugged and sparsely vegetated area near Sogwass Mountain in Northern Uganda. We were not convinced that this rarely used smugglers’ route was even passable, let alone legal for access to the border—then we got caught. The tribal militia met us with a combination of crooked smiles and blank stares; two of the men unslung their HK G3 rifles, coming to the low ready. Walking toward the GWagen the leader’s grin broadened, his eyes shielded by mirrored aviators and a baseball cap emblazoned with “Disobey” above the bill. Bryon and I continued to take stock of the approaching party, a mix of camouflage and traditional cloaks, some even gripping wooden staffs and bows and arrows.

This adventure was an opportunity for Bryon Bass (contributing editor) and me to explore Central Africa, driving one of the rarest of expedition vehicles, the Mercedes Geländewagen 461. These Entdeckers were prepared by Front Runner for global travel and only 12 were manufactured. We were also joining a crew of seasoned adventurers, gentlemen that had crisscrossed most of the globe: Stanley Illman (Front Runner’s co-founder), Alex Beccaria (designer for Entdecker), and Franz Czepek (racer and engine builder) allowed us to join their much-venerated ranks for a trip across Kenya and Uganda.

THE EQUATOR AND THE WONDERS OF UGANDA

Every good Africa story should start with a fixed gear Cessna and a dirt runway, and this one begins a few hours from Nairobi in the prominent shadow of Mount Kenya. Even more entertaining is that the plane was owned by a Kenyan by the name of Jamie Roberts, who happened to buy the aircraft years before from our Stanley—curious indeed. Mr. Illman realized it was his old plane’s tail number while driving past Nanyuki Airport in his Entdecker. Fascinating, given that Stanley owned the Caravan 208 in South Africa, and this was Kenya. Such is the way of the traveler, proving once again that the world is indeed very, very small.

Taxiing up to the tin-roofed Tropic Air “terminal,” we unloaded the plane and our pile of gear, shuttling it to the waiting line of G-Wagens. Not in a big rush, this provided the chance to get organized and drink a few beers while loading the fridges, lashing the bags and boxes, and installing a new set of rear shocks on our unit. It might seem that the G-Klasse eats shock absorbers, but that could have more to do with the pace of these (actual) rally drivers than the engineering of the dampers. We were also content with taking our time as we were staying at Soames Hotel and Jack’s Bar, a local hangout for expats, British military, and wayward vagabonds; the watering hole was rich with intel and cautionary tales.

After a few days of mostly doddling, drinking, and provisioning, we headed toward Uganda, and I almost immediately “ran out of gas,” the glorious Mercedes turbo-diesel sputtering to a stop on a narrow stretch of highway. In a modest attempt at self-defense, we were heading to the gas station and had somewhat intentionally transferred from the main tank to the secondary tank to ensure everything was topped off. Nevertheless, I was stuck between a culvert and an onslaught of tuk-tuks. Through a combination of moving a few gallons back to the stock tank, “Stanley-voodoo,” and a few key cycles and flicks of the pump switch, we were finally on the road—shaken, not stirred.

It is funny how we anticipate travel experiences, expecting these idyllic scenes and Instagram #youdidnotcampthere photographs. Well, my first crossing of the equator happened without me even knowing it, and then it happened again. I was anticipating the sign, weathered and in perfect patina, but it never appeared and I never checked the GPS. Despite this folly, I was not particularly upset, thoroughly satisfied by the beauty of the Subukia Rift Valley, dense with agriculture and humanity, the cradle of life indeed.

After a night of camping, it was time to cross the Ugandan border, situated at a river crossing along a dusty track at the base of Mount Elgon. The officials were happy to see tourists and made the entire process pleasant, down to the cobalt blue silk blouse and perfect smile of the woman who helped us. From the frontera, we meandered around the mountain, an extinct shield volcano with a respectable 4,321-meter summit; its caldera is one of the most expansive and intact in the world. Continuing west, we drove through village after village, in nearly every instance greeted by children waving and jumping up and down. Thatched roofs with branches for walls provided modest shelter, but these people seemed happy and the entire region resonated with me, reminding me of the beauty of simplicity and community.

KIDEPO AND BURNING PALMS IN SOUTH SUDAN

Traveling north, our destination was the Kidepo Valley National Park, a 1,442-square kilometer reserve bordering South Sudan, home to open savanna and over 80 species of mammals and 500 avians. We entered through a little-used gate at the south end and completely surprised the unexpecting ranger. After filling out the logbook, he discovered that he had forgotten the combination to the safe. “Pay at the main lodge” was his response, and he opened the gates. We were one of only three guest groups in the entire park.

For several days we crisscrossed the valley and experienced endless game sightings. For about $40 per day, we camped in the open and enjoyed the company of Denis Odong, a ranger and our protector from both four- and two-legged predators. He carried a well-worn AK47 with a single loaded magazine and no round in the chamber. I asked when the last time was he shot the weapon and he replied, “About 4 years ago.” I quietly asked Denis if anything really bad should happen, would he just hand me the carbine? He agreed, looking more relieved than concerned by my request.

Each campsite was better than the previous, the last perched high atop a knoll in the center of the Narus Valley. A flat-topped rock outcropping had made for ideal parking and sleeping, along with an uninterrupted view of the area. Other than one angry elephant, nothing went bump in the night. In the morning, we gently suggested to Denis that we would like to drive into South Sudan, which shared a border with the reserve and conveniently had an abandoned border post. The Ugandan military was there, but we generally agreed that there would be few Sudanese because of the current civil war. With that, we fired up the G-Wagens and headed north, barely crossing into the neighboring country to explore a massive palm forest. When we turned around and headed back into Uganda, Denis looked visibly relieved.

ROGUE BORDERS, BOWS, AND ARROWS

We started to encounter problems with Alex’s Entdecker: the 24-volt alternator was no longer providing power. The system has redundancy with a 12-volt alternator as well, but this creates several problems since the 24-volt system is responsible for starting and a few other functions. Because of this, we attempted to charge individual batteries from the remaining alternator. Many efforts were made to repair it but to no avail. Franz and Stanley were impressive to watch, and it seemed like they relished every chance to work on the Mercedes, laying out tarps and tools and working in the true South African way: ’n Boer maak ’n plan. Anything that went wrong required immediate attention and repair, which I believe speaks to their experience in the field. Stanley said, “Don’t wait until something gets worse, fix it now, and properly.”

Even with a wounded G-Klasse, Stanley suggested we take an old smuggler’s route from Uganda into Kenya. There might be a border post was his justification, but we all knew this was unlikely. The track would be both remote and technical, and arguably legal. Just getting to the mountain pass took us through rarely visited villages, the people stunned by our convoy. Thatched roofs dotted the hillsides and young boys tended sheep; one child, maybe 5 years old or so, stood holding a lamb and a staff, lord of his hectare.

We continued to climb, the road becoming increasingly narrow and rough, the occasional boulder sliding into the track from above; erosion became more prominent and tire placement was now a consideration. Rounding an exposed shelf we encountered a tree across the path. It was evident a few motorcycles had made it past, but we were the first 4WDs to arrive in some time. Out came the gloves and winch line for a quick trail repair, a combination of hatchet and Warn clearing the way. From that point the difficulty increased: large rocks and washouts slowed the pace and required regular marshaling. The last few switchbacks were to bedrock and the Geländewagens stepped down carefully, the risk of trail damage high.

At the bottom of the canyon a few more obstacles remained, and now on the Kenyan side of the border, the lead vehicle with Stanley and Franz sped ahead into the open basin. Bryon and I were last onto the flats and turning through a large bend when we noticed armed men emerging from the brush. Bryon stopped short, about 100 meters behind Alex and the second truck in our convoy. The men were clearly agitated, and every able-bodied villager was descending on our group, several carrying G3 battle rifles and others grasping AK47s. Even more carried staffs, farm tools, and bows and arrows. This was quickly going to go one of two ways.

Fortunately, Stanley’s experience shined. He casually stepped from the Mercedes with his wild white hair, shorts, Izod shirt, and dusty Crocs over sockless feet. A big smile led the way and he bellowed a “hello” to our hosts. They didn’t smile, but were clearly taken off guard; rifles were lowered and the tension began to ease. A leader emerged and had a brief conversation with Stan and Franz. A few minutes later they began moving toward Bryon and me, still held short. Almost simultaneously, we removed our aviators and did our best at displaying the same disarming smiles. They were not amused and asked us a few questions, obviously verifying the story of Stanley and the others. One thing was clear, we were going to the police station.

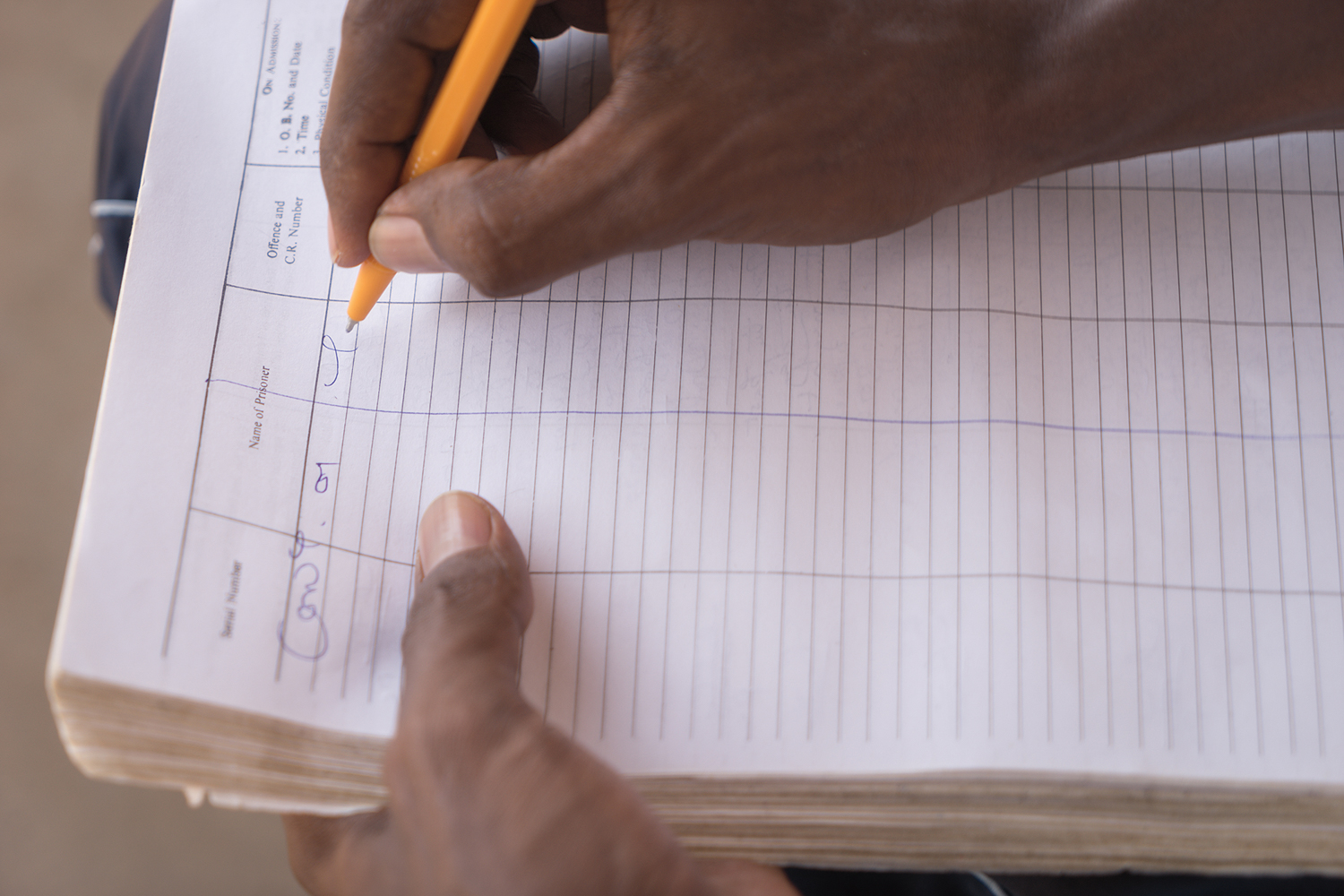

With a few instructions and a stern warning that the police would be waiting for us, they radioed ahead and we drove the few miles to the enclave of Oropoi. Just finding the building was difficult as it was tucked in a nondescript courtyard, with a few stray dogs lounging in the shade. When we rolled in, a few officers emerged from a fractured doorway in various states of dress and uniform. They were also not happy to see us, their annoyance more evident than anger. An officer took our passports and inspected our visas, recording the details of our documents and infraction in a broken and tattered logbook. Without a word to us, he told Stanley, Franz, and Alex to leave—he had further plans for Bryon and me.

They wanted to search our vehicle and started with a small innocuous gray bag Bryon had in the passenger footwell. Out spilled every manner of paraphernalia, from a compass to paracord. This raised the official’s eyebrows and with a stiff open hand he motioned to the pile and said, “What is this?” Improvising, I grabbed the most touristy item, a spork, and replied, “For camping.” He was far from convinced and demanded to know what our mission was, to which I responded, “We are just tourists.” “You are supposed to disclose your mission,” he growled, clearly still agitated. I remained silent. Frustrated, he shoved our passports back toward us and waved at us to leave. While loading up he took several images with his cell phone. Again he grumbled, “You are supposed to disclose…” as the Mercedes clattered to life. Onward.

Northwestern Kenya is cattle country, complete with cowboys and stolen livestock, and regular battles between tribes—the AK47 is as common as a cell phone, the area a far cry from the opulent safari lodges of the Maasai Mara in the south. Most overlanders travel on the eastern side of Lake Turkana, but we were dodging potholes on what remained of the old British colonial A1. The road was so abusive that Stanley lost both rear shocks, the tail of the G-Klasse bobbing with each impact. Alex’s G-Wagen was also giving him trouble with the charging system and all attempts at remedy were failing. We needed a new battery since one was off-gassing into the cabin, the result of overcharging. We pulled into Lodwar and “Team Stanley” went to work. Soon, a crowd formed and one particularly surly local decided that I was to be the target of his torment. His breath reeked of alcohol and his eyes were wild and bloodshot. He wanted money and told me that he was a fighter. “I fight for money,” he yelled while making a fist. The condition of his hands was evidence of this truth: swollen knuckles, with fingers and wrist disfigured from constant abuse.

At first, I just tried to ignore him, but his aggression increased. “Come on Mr. Military Man, give me some money.” By this point, Bryon had taken notice and moved to my side of the Mercedes. The situation was escalating, and it was clearly going to get physical. Despite my height and size advantage, this was heading quickly in the wrong direction. This guy made a living beating people up and getting beaten up. Ignoring him only made him angrier and any attempt at discussion made him bolder. My hand rested on the hilt of my fixed blade, casually at first, but as he closed into my space nearly touching me, I gripped it tightly. Apparently, the locals could also see where this was going and one older gentleman intervened, grabbing the man by the arm and pulling him away. “You take me to America!” was the aggressor’s last comment as he slid into the crowd and out of sight.

THIS IS AFRICA

Adventure comes in all forms, from climbing mountains to crossing countries. Every new experience, both good and bad, forms who we are as travelers. Africa is all of this and more, a massive continent with a biodiversity unmatched on the planet. This place has also experienced unimaginable tragedies, along with colonists, dictators, and warlords all ripping it apart. However, the people remain (mostly) kind. The women impressed me the most, with an ever-present work ethic and determination to provide for their families. Bryon and I picked up a woman and her children to drive them to school, a distance of 19 kilometers from their home—they normally walk.

Despite a few lively encounters (thankfully, all benign), my love for this cradle of humanity has only grown. It certainly helped that we were driving rarified vehicles, but much of the enjoyment came from the companionship of truly interesting teammates, their lives as diverse and storied as any I can imagine. This realization came full circle when Bryon handed me a typical looking rock, a few chips evident along both sides. “Check this out, an early hominid chopping tool used to crush bone to access the marrow—well, it’s the early human multi-tool.” Bryon has a PhD in archaeology, and within 10 minutes at our campsite had found tools that represented millennia of human activity in the area. Scrapers, projectile point fragments, and miscellaneous finds were all laid on the hood of the G-Wagen. I asked Bryon how it was possible that all of these artifacts could be right here. He responded, “Probably the same reasons why you were drawn to this place to camp is why all of these other humans stopped here too. Protection, proximity of water and other resources, a flat place to sleep.” I thought about that for some time, the sound of “Team Stanley” in the background fixing something loose on the vehicle. From the ancient hunter-gatherers to present-day cattle herders, to us. A good campsite, a few tools, a meal cooked over the fire, friends to laugh with. We are far more alike than different.

2 Comments

Clint van Blanken

September 4th, 2018 at 9:12 pmLove the look of the map at the end of this story. What map program or graphic is this from?

Greg Illes

September 5th, 2018 at 9:00 amYour observation about the armed ranger in Kidepo reminds me of our recent travels through Namibia and Zimbabwe. There, we were in the company of licensed guides, not rangers. The guides must “qualify” with their weapons four times a year (at a rifle range only).

Those guides were definitely prepared against large game problems, not poachers or insurgents. Their lightest caliber of choice was 375 H&H, and many went for the 458. We did run into anti-poaching patrols — strictly AK-armed.