Editor’s Note – Valentina Vallinotto’s father, Angelo, was an ambitious explorer. Piling his young family into a series of Land Rovers, IVECOs, and Toyotas, he tackled uncharted routes across North Africa and the Sahara Desert throughout the 1960s all the way until the early 1990s. The 1970s was a particularly exciting decade for overland adventurers on the African continent, as many newly independent countries were opening their borders to travelers but were still very undeveloped, and vehicle routes were all but unknown. Below, Valentina shares her memories and her family’s amazing photography from those travels.

Angelo Vallinotto, in Arabic attire, shot this “selfie” with a spring-action timer on a fully mechanical Leicaflex camera. Inspired by the 1962 epic Lawrence of Arabia, which won 7 Oscars, he set out to explore the vastness of the Sahara.

“Mummy? Where is Daddy?”

“Daddy is studying; he is studying his African maps.”

My father, Angelo, spent hours studying his next itinerary across the Sahara desert almost every night.

He often went to Paris from our home in Italy, where he knew he would find 1:20,000 scale paper maps and precious aerial photos of the former French colonies in North Africa. In our family home, I still keep his big orange folder with these maps and images, his Opisometer for estimating distances and fuel consumption, his compass, and his tire pressure gauge.

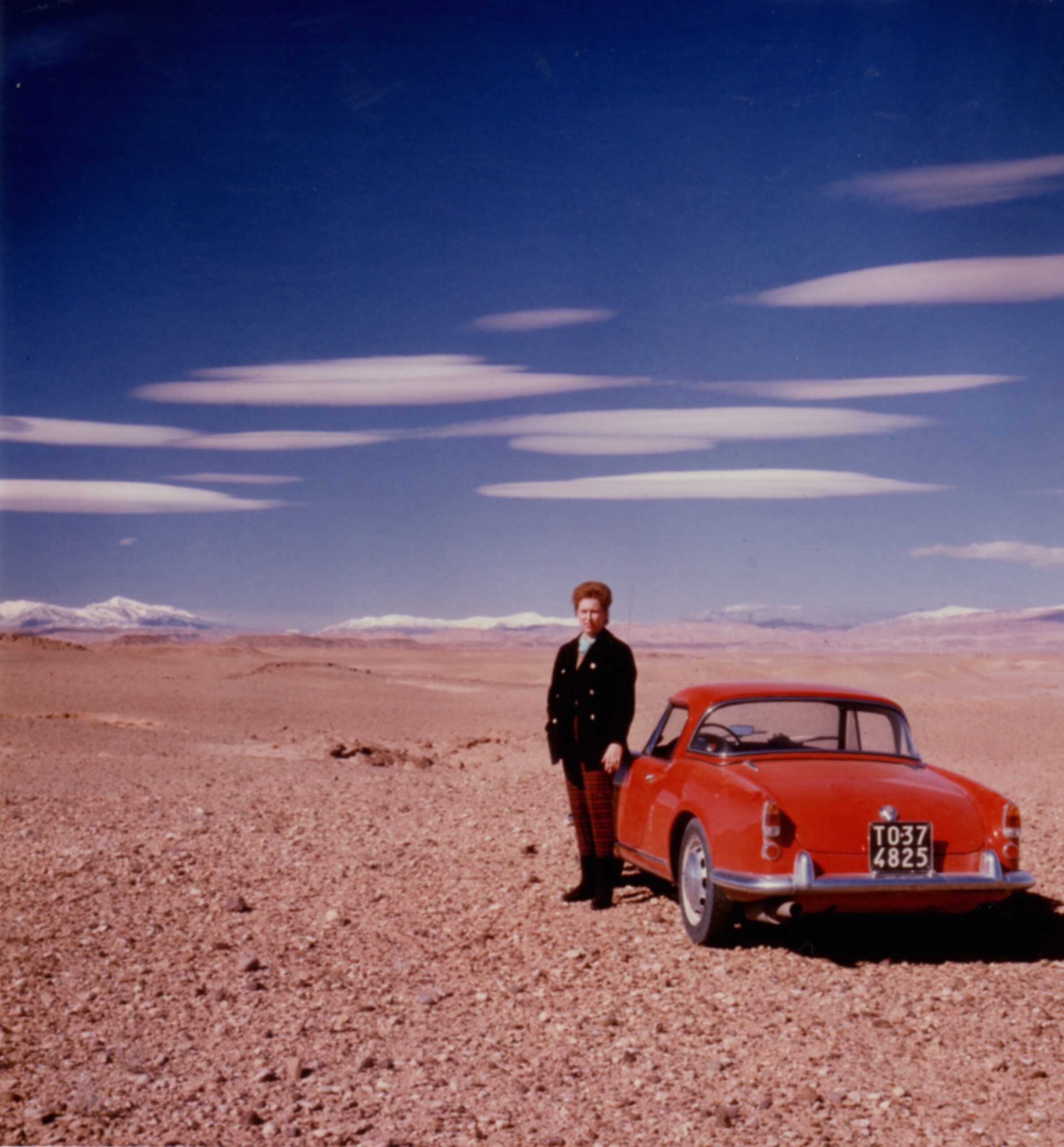

His intense passion for desert travel started in 1962 after seeing the movie Lawrence of Arabia: an epic historical drama shot in the Jordanian desert. One year later, he drove his new bride, my mother Rosanna, a city lady from Turin to Southern Morocco: 4,000 miles in total and 1,500 miles of dirt roads in a red Alfa Romeo Giulietta Spider. His African addiction kept pulling him to overland the Sahara for two to three months each winter until 1992.

Rosanna Damiani Vallinotto, my mother, with the red Alfa Romeo Giulietta somewhere in Morocco.

After this first crazy adventure, he realized the Giulietta was not the proper vehicle for this kind of overland trip, so he bought the iconic vehicle for the African deserts: a Land Rover Series IIA. Other overland vehicles came after this first one: in the 1970s, two other Land Rovers, in the 1980s, Toyotas FJ45 pickups, then a FIAT OM 75 commercial truck. I named it “Maciste”: an Italian movie character from the 1910s, a Hercules-like figure with enormous strength. Unfortunately, Maciste was too big and heavy, affecting fuel consumption. Fuel range is critical when you have to cover hundreds of miles in the middle of nowhere with just a few unreliable gas stations. So, in the 1990s, his last overland truck was a Toyota Land Cruiser FJ75 pickup with a rooftop tent.

My father was my hero, and while I was always happy and excited to help him customize the vehicles, handle the camping gear, and pack the storage compartments, none of these journeys were mine. I always asked: “Daddy, when shall I come to Africa with you?”

At that time, traveling on the continent required many vaccinations, and clean water and fresh food were not always available or reliable since we had no fridge. In addition, I often contracted bronchitis, so my parents were understandably concerned. However, I was stubborn and persistent, and a daddy could say no to his only daughter for only so long. So, in 1978, extending my winter holidays, I started my overlanding life.

Memories of those travels are fixed in my brain even after 45 years.

There’s no camp without a campfire. On the front bumper of the Land Rover sat the red plastic basin, which mummy used to wash dishes. The same water was used to keep the wooden handle of the hammer in place in the head, preventing it from shrinking in the extremely arid desert air.

Shifting sands often erased the trails, making navigation a real challenge without GPS. In these moments, micro-navigation was crucial. As a rule of thumb, we kept a safe distance between vehicles, ensuring that if one got stuck in the sand, the others wouldn’t follow suit.

After days of sand and rock in a sparse desert landscape, we reached the Oasis of Timia. Amidst this transformation, my mother observed a donkey circling tirelessly to operate a Noria, a traditional Persian well system, symbolizing endurance and ingenuity in the harsh environment. Timia Oasis, Niger.

The Hoggar Mountains are a highland region in the central Sahara located in southern Algeria. One of the most striking features of this region is its rocky pinnacles, which create a dramatic and otherworldly landscape. Assekrem, Hoggar Mountains, Algeria.

Saharan dunes, though not the tallest, impress with their prominence. Rare rainfall causes the ground to release salts, giving the sand a whitish hue at its base. Sparse vegetation thrives along lines, marking the presence of the last underground water sources.

- When Daddy purchased this FIAT 75 flat-bed truck, it was branded OM. Later, when the Italian army began using them, the brand changed to IVECO. Daddy designed a camper with corrugated metal sides to enhance its structural strength.

- Mummy and I nicknamed the truck “Maciste,” after the Hercules-like figure known for his immense strength and heroic feats beyond the reach of ordinary men.

The Tuaregs, a nomadic and culturally rich group, faced formidable challenges in the 1970s. They identified more with the Sahara Desert itself than with any single country and harbored a strong desire to maintain their autonomy and traditional way of life. Tassili n’Ajjer, Algeria.

I remember this incredibly windy day. As a sandstorm approached, we had only a brief moment to marvel at the 300 million-year-old fossilized trees scattered around us. Petrified Forest of Marandet, Niger.

In the late 1970s and 1980s, Toyota 4x4s gained dominance in Africa for their durability in tough conditions and low maintenance needs. During that era, my father opted for a pickup Land Cruiser HJ45.

The legacy of colonial boundaries, which divided Tuareg lands among different countries, persisted in disrupting their traditional nomadic routes and unity. Post-colonial governments frequently marginalized Tuareg communities, exacerbating tensions and triggering rebellions.

The mud mosque of Agadez is the tallest mudbrick structure in the world, standing at about 88 ft (27 m). It was originally built in the 16th century, around 1515, and is periodically maintained by the community, which applies fresh layers of mud to reinforce and preserve the mosque. Agadez, Niger.

The Tuaregs are known for their matrilineal society, where lineage and inheritance are traced through the mother’s line. Despite being Muslim, their practice of Islam is deeply entwined with their cultural heritage and nomadic lifestyle. Unlike some Muslim communities, Tuareg women typically do not cover their faces with veils.

The black diesel engine smoke bore witness to our friend Pierre’s challenges as he navigated his overloaded Series III Land Rover through soft sand passages.

This pink dress wasn’t my typical overland outfit. After a full week in the dusty desert, we finally reached Tamanrasset. At the campground, we were able to have bucket showers at last. So, I decided to celebrate the occasion by wearing a pretty dress. Tamanrasset, Algeria.

Read More:

The Overlanding Code to Happiness

Our No Compromise Clause: We do not accept advertorial content or allow advertising to influence our coverage, and our contributors are guaranteed editorial independence. Overland International may earn a small commission from affiliate links included in this article. We appreciate your support.