Photography by Enrique Pacheco

Western Europe is not exactly a paradise for overlanders due to restrictive laws regarding off-roading and free camping. In turn, countries on the continent’s Eastern side, especially those in the Balkans, abound in what their occidental counterparts lack: looser regulations and fewer off-pavement prohibitions, with vast areas of stunning nature still seemingly untouched by mass tourism. Among the countless things to see here are the unique, alien-looking monuments called spomeniks, a testament to the region’s struggle and revolution against fascism in World War II.

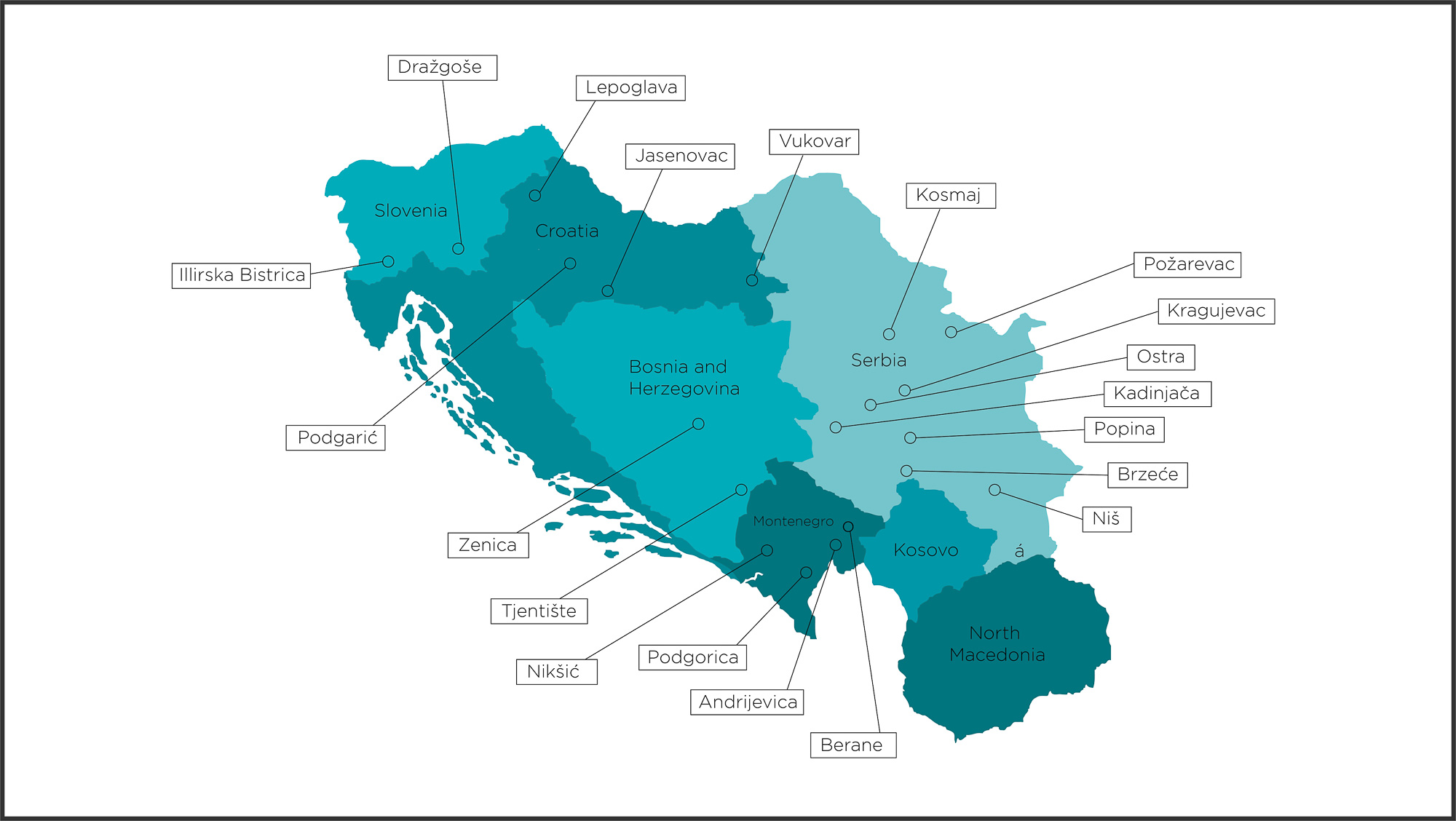

Spomeniks are scattered all over the territories of the six republics that once formed the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. Some of the most impressive monuments were built on actual WWII battle sites. Their remote locations, sometimes well outside of inhabited areas, are significantly more convenient to visit in a camperized vehicle, especially if you’re hoping to see them at sunrise or sunset. Four-wheel drive is unnecessary, but Balkan mountain roads can be challenging for an unpracticed driver, especially in the wintertime.

To a visitor unfamiliar with the region’s complicated past, spomeniks might seem purely abstract, random in location and design, and devoid of any meaning. There is a bigger story to be told, though. After WWII ended and a new, socialist Yugoslavia came into existence, both the perpetrators and the victims of horrific war crimes suddenly found themselves linked together into one country and one nation. The government had to find a way to create a modernized kind of patriotism, a base on which to build the “brotherhood and unity” of the Yugoslav people. These bold, abstract artistic visions shifted the focus away from the actual war crimes and toward the impressionist feelings of loss and suffering, ushering in a bright, shared future.

In 1948, Yugoslavia’s leader, Josip Broz Tito, parted ways with Joseph Stalin and the USSR, aiming to create a “third way” for those nations that wished to be excluded from the increasingly polarised world of the Cold War era. These ideas resulted in the creation of the Non-Aligned Movement, and Yugoslavia’s newfound status as one of the leaders of the emerging “Third World” meant it now needed an identity completely separate from other socialist countries grouped in the Eastern Bloc. Is there a better way to make a country culturally distinguishable than through art? Spomeniks stand in sharp contrast with socialist realism, the artistic style used by the USSR and its satellite states, and its immense, realistic statues of the “common worker” straightforwardly expressing Soviet ideals.

Many spomeniks were erected in city centers, parks, and frequented avenues. The most imposing ones stand on battle sites, secret meeting places of the resistance fighters, or locations where unspeakable horrors were committed, dominating and defining the landscape surrounding them. They honor both victories and losses and, above all, the human lives lost in the liberation struggle.

It is hard to define which Yugoslav monuments qualify as spomeniks as not all of them are abstract in style or grandiose in size. They were never cataloged, but we do know that by 1961, 14,000 had been erected at sites all over Yugoslavia.

Yugoslavia split apart through a series of armed conflicts stretching through the 1990s. Many of the spomeniks in war zones were destroyed, a symbolic purge of the old socialist system and way of life. The ones that remain standing are in different stages of decay, usually neglected by current governments, as the events they commemorate are no longer important for the national narratives.

Practical Tips for Visitors

Spomeniks can be found in Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, Serbia, Kosovo, and North Macedonia. These seven countries are quite small, spanning a little over 1,000 kilometers from the northwestern corner of Slovenia to the southeastern border of North Macedonia. That said, the monuments are numerous and often in remote places, and the roads are usually far below the European standard. Whatever your chosen itinerary, getting from one spomenik to another will almost certainly take longer than estimated; be sure to plan for extra time.

You will notice that some monuments are a short distance apart but located in different countries. Crossing borders more often than necessary should be avoided as the wait times sometimes amount to several hours. Visiting all points of interest in one country before continuing to the next will save you time and reduce stress.

We visited the following monuments on two separate trips dedicated solely to spomeniks; even so, we still managed to explore only five ex-Yugoslav countries. Including too many sites in your itinerary will only make for an overbearing journey, so when in doubt, opt for fewer (well-chosen) monuments instead of trying to cram them all in.

Slovenia

The westernmost of all ex-Yugoslav republics, both geographically and culturally, Slovenia is a wonderful place to start. The spomeniks in Slovenia are usually found in a fair state, although a little forgotten.

The monument structure in Dražgoše doubles as an observation point, with open vistas of the town and the battlefield below. The shape is evocative of a hayrack, a typical sight in the rural parts of Slovenia. The message is that the victory over fascism would not have been possible without villagers whose humble but numerous efforts ultimately led to freedom.

The complex in Ilirska Bistrica holds the remains of 284 Partisans (the communist-led anti-fascist resistance to the Axis powers) underneath the concrete cube monument. This region of Slovenia is world-known for an extensive cave system (Postojna and Škocjan), and the monument’s shape invokes the caves’ emblematic stalactites and stalagmites, as well as the bones of the fallen soldiers lying below.

Croatia

Croatia’s gorgeous landscapes make it easy to forget about the bloody conflict that took place here in the 1990s. In the war zones, many of the largest, most important spomeniks were destroyed or taken down. However, one still stands alongside a memorial center and museum: the Stone Flower in Jasenovac.

Jasenovac was a forced labor and extermination camp and the most notorious death camp in occupied Yugoslav territory. The number attributed to Serbian, Jewish, and Romani lives lost here varies greatly depending on the source and is generally estimated to be around 100,000.

Jasenovac was Yugoslavia’s biggest open wound. The leadership thought long and hard about how to adequately commemorate a site that witnessed such horrors without reawakening past trauma. Bogdan Bogdanović, the artist behind the ethereal Stone Flower, did not envision a memorial invoking war horrors and death but instead opted for a more figurative composition meant to inspire feelings of forgiveness. The complex is replete with symbolism: the symmetrical lotus flower stretches its petals toward the sky, and its roots, invisible at first glance, dig deep underground and safekeep a crypt.

Jasenovac saw armed conflict in the 1990s, alongside countless attempts of vandalism and destruction. Seeing the looming danger and the complete lack of institutional protection, the assistant director of the memorial site packed what he could out of the museum’s collections and kept the artifacts safe in his apartment for years.

Jasenovac remains a highly divisive piece of history to this day. There are security cameras everywhere, and during our first nighttime visit, we were approached by the local police, who were friendly but wanted to know exactly what we were up to.

During WWII, the remote hills surrounding Podgarić hid a hospital complex, which doubled as a cultural, political, and military center for the resistance. Many have found the shape of the strange central statue similar to the ancient Egyptian winged sun; I see something straight from a Pink Floyd album cover. The monument presently lacks any illumination, and the complete darkness surrounding it makes for a formidable first impression when visiting at night.

Lepoglava’s notorious political prison operated as a death camp during WWII, in which several thousand lives were lost. The memorial park stands on the spot where the camp’s victims were buried in mass graves. The abstract sculpture central to the cemetery is a prime example of uniquely Yugoslav abstract expressionism. Where another nation would have erected a touching memorial invoking the atrocities of war, Yugoslavia chose to place this conceptual statue instead.

The spomenik in Sisak marks the location where young Communists founded the first Partisan brigade in 1941, thus kicking off organized resistance in Yugoslavia. An elm tree was originally planted at the site, and the present-day monument emulates the tree’s shape and branches.

Vukovar monument honors an estimated 455 civilians executed by Ustaše (Croatian fascist movement) forces and buried in mass graves here between 1941 and 1943. The memorial was heavily damaged during the town siege in Croatia’s Independence War in the 1990s. This conflict birthed another unintentional memorial to the war: a heavily bombed water tower that still stands unrepaired, predominantly considered a symbol of the town. The spomenik complex has been renovated since and now remains in decent shape, although well outside of any tourist routes.

Bosnia and Herzegovina

Historically a melting pot, the country is shared by Serbs, Croatians, and Bosniaks today. The territory saw the most vicious of war scenes in the 1990s, and with them came some of the most complex erasure of the Yugoslav legacy.

Even today, daily politics are tainted with ethnic tensions and rivalry, which mark a definitive distinction between “us” and “them.” In many places throughout Yugoslavia, but especially here, markers of the old country were torn down and replaced with symbols of the new nationalistic ideologies, most notably through the construction of religious buildings. Despite it all, Bosnia and Herzegovina is a wonderful, authentic place, well worth the visit, and overwhelmingly safe for international travelers.

Tjentište Valley was the stage for the Battle of Sutjeska (1943). The Partisans, trapped between Axis lines, orchestrated a daring escape operation for Tito at a great cost of life—over 7,000 soldiers died ensuring his safe passage. The outcome established Partisans as a significant military force and a critical player in the war. Sutjeska served as a foundation of Yugoslav patriotism and the myth of the leader’s superior persona.

This spomenik was and remains one of the most widely known. Its symbolism works on three levels. The monument’s soaring shape is an abstract rendering of “the wings of victory,” and the structure’s unique position in the valley makes it visible from the entire battlefield below. It stands guard above it, marking the way to the heavens for those who have fallen. Finally, the portal-like passageway points with precision in the direction the Partisans escaped, serving as a sort of battle compass in the landscape.

The monument was almost destroyed during the Yugoslav wars. A Bosnian Serb Army commander had every intention to blow it up and did not do so only because his unit did not carry enough dynamite. The sculpture had been neglected for a long time, but it recently underwent a thorough cleaning, which transformed the concrete from a desolate gray back to shining white.

The area around the monument is safe to visit, but bear in mind that landmines can still be found in the wider area of the park. Exercise caution and do not walk or drive outside of the marked trails.

The monument in Zenica resembles a pitchfork, a common symbol of popular uprisings. The design is peculiar in that the highly polished aluminum body of the obelisk makes it visible from the city below, but only at certain times of the day when the sunlight hits it just right. In this sense, the monument is just like a painful memory: it resurfaces suddenly and when we least expect it.

Montenegro

The small mountainous country of Montenegro hides some of the last true wilderness in Europe. The final nation to leave Yugoslavia, Montenegro keeps the old country’s artifacts in good condition.

The Nikšić monument bears highly intricate decorations. On its face, some see a gearwheel, standing for ruthless “gears of war.” Others see a flower, embodying rebirth. No matter what you see, a prominent five-pointed star, a significant symbol in Yugoslavia’s history, dominates the image.

The memorial in Podgorica is an example of an art piece intended for active public use, as it includes an amphitheater. The work follows a theme of journeying through time and space, with a flowerlike statue in the center, symbolizing the optimistic Yugoslav present and future.

The six pinnacles of the monument at Andrijevica represent the six Yugoslav republics, each distinct and unique and still bound together by the eternal flame burning between them.

A strange conic tower surrounded by a slew of engraved stones stands alone in a somewhat isolated forest just outside the town of Berane, paying respect to those executed on this site during the war years.

Serbia

Yugoslavia’s legal successor, Serbia, is where its legacy is most noticeable, even though the country’s current policies are far from socialist. Belgrade, Yugoslavia’s old capital, is replete with history and deserves a visit.

The Spark of Freedom is located on top of Kosmaj Mountain, making it visible from almost everywhere in its surroundings. The structure’s shape bears a clear resemblance to a spark. With a change of perspective, another outline becomes apparent: when inspecting the monument from its center or from the air, the shape shifts to form a five-pointed star.

The chaotic-looking statue in Požarevac is the odd one out—it honors the Soviet Red Army, whose soldiers liberated the city in 1944.

The Interrupted Flight in Kragujevac tells a heartbreaking story. In 1941, German soldiers executed hundreds of schoolchildren at this very spot in retaliation for Partisan resistance. This event was a defining tragedy for Yugoslavia, serving as an example of the occupier’s cruelty. The sculpture is shaped like a bird trying to take off but unable to do so because of a broken wing. When examined more closely, eerie shapes of children’s faces protruding from the monument become visible. This was one of the first spomeniks, and it is a good example of the emergence of the distinct Yugoslav style: great suffering rendered in abstraction.

The gravity-defying monument at Ostra has peculiar company, a Serbian Orthodox church. A passerby told us the story: The site was designated for a church before WWII began. Post-war, the church project was abandoned in accordance with the country’s official policies. After the fall of Yugoslavia in the 1990s and a subsequent upsurge of religious sentiment, the idea was revisited. Today the church is active and well taken care of, while the spomenik, only some meters away, is in a state of disarray.

The majestic memorial at Kadinjača consists of a legion of white concrete pylons protruding from the earth at different angles. The bullet hole formed by the two tallest pylons points directly toward the town of Užice, the first liberated Yugoslav territory in WWII.

The Sniper, the otherworldly monument at Popina, comprises three separate elements, which, when aligned properly, form a tunnel or portal. The eerie echo effect that occurs when one is standing inside the structure makes the site even more mystical.

Two strikingly tall pillars meet halfway and form Brzeće’s monument. Located close to the Kosovo border, it symbolizes the Serbian and Kosovar ethnicities coming together to fight against a common enemy. How times have changed.

The three fists bursting from the ground in Niš mark the location of a prisoner of war camp and tell the story of brave prisoners who were executed with their fists high up in the air, defying the enemy even with their last breaths. The statues have different heights, indicating that men, women, and children were killed here indiscriminately.

The Future

Over the last decade, spomeniks have sparked new interest, especially in international visitors, who saw the strange structures with fresh eyes. Many find the monuments charming precisely because of their deteriorating, almost apocalyptic aspect. Tourism ultimately brought spomeniks back into the focus of local communities and governments. With more interest came more investments into the upkeep of the sites, so their future is looking bright.

Resources

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in Overland Journal’s Winter 2023 Issue.

Please enjoy Episode #169 of the Overland Journal Podcast: Ibérica Overland on What You Should Know About Overlanding Spain

Our No Compromise Clause: We do not accept advertorial content or allow advertising to influence our coverage, and our contributors are guaranteed editorial independence. Overland International may earn a small commission from affiliate links included in this article. We appreciate your support.