Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in Overland Journal’s Spring 2022 Issue.

First synthesized in the late 1850s, Sigmund Freud was an early advocate of cocaine in addition to being an addict, prescribing it for depression and other conditions. In the late 1800s, coca leaves found themselves on the ingredient list for Coca-cola, and in subsequent years, cocaine was broadly used in tonics and wines across all social classes.

The indigenous people of the Andes chewed the leaves of the coca plant long before the arrival of Europeans. Coca was a gift from Pachamama, an Earth Mother goddess, to improve their lives in the severe high-elevation conditions. But its stimulant properties found a new purpose when local populations were forced to work under brutal conditions for the newcomers. With a pinch of Cal lime and a wad of leaves, the urges for food and water were suppressed, as was fatigue.

The late 1980s saw the United States and the rest of the world awash with cocaine. Although it had been on the scene for many years, there was a significant increase in consumption, and it was no longer considered a “rich man’s” drug.

The majority of coca is grown as a cash crop in Bolivia and Peru, as well as Colombia and Ecuador. Coca leaves are processed into cocaine in a series of steps in primitive laboratories deep in the jungle. It is first made into cocaine paste using sulfuric acid, kerosene, and sodium bicarbonate. The coca leaves are soaked in a solution of water and sulfuric acid in a long, above-ground trough (pozo), then stomped on for hours, causing the leaves to release the coca alkaloid into the liquid. After eight to ten hours, the liquid is collected and poured into another smaller pozo. Kerosene is added, which causes the solution to separate, and the lighter alkaline solution, called agua rica, floats to the top. The “rich water” is then collected and poured into a large bucket where sodium bicarbonate is added until there is a slurry, which is passed through a cloth to filter out the cocaine paste. The paste is squeezed to remove as much liquid as possible, formed into a ball, and wrapped in pink toilet paper. It’s gathered and brought to an area where a buyer purchases the paste balls for US dollars, then is flown to Colombia from one of many clandestine airstrips for final product processing.

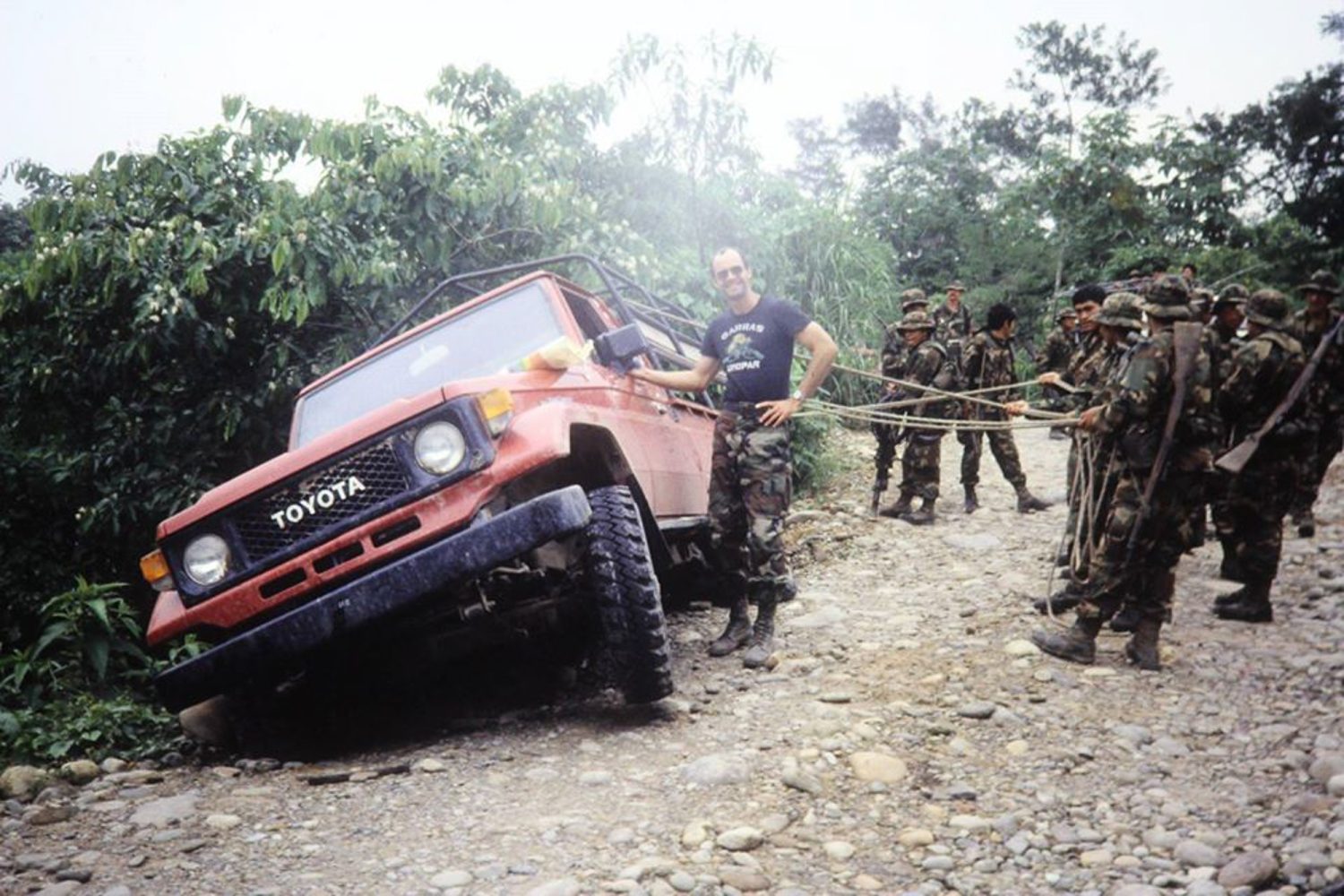

The US Government, trying to stem the tide of cocaine, formulated a plan to attack the sources of the drug. Elite teams of special agents of the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) and border patrol tactical agents (BORTAC) were inserted into these source countries to interdict the jungle labs and smuggling aircraft. I was one of those agents, and in 1988, I went to Bolivia. I should mention that I am half Bolivian; my father was Bolivian. Growing up every year, we would spend the month of February visiting family in Cochabamba. This gave me an advantage over my teammates, most of whom had never even left the USA before.

My team was assigned to a Bolivia Anti-Narcotics Police (UMOPAR) base camp at Chimore in Chapare, Bolivia, known as El Infierno Verde (the Green Hell). We also worked with a Green Beret A-Team who was already at the camp. Chimore was where most of the coca was grown and processed into a paste. In addition to the locals growing and processing the coca, there were many Colombian buyers and their sicarios (hitmen). The Bolivian government declared this area a “red zone” due to the narco activity and associated violence.

My first exposure to Land Cruisers was when I reported to the US Embassy in La Paz, Bolivia, (elevation 12,000 feet). A couple of volunteers were needed to drive to Cochabamba and then to Chimore. My buddy Tom and I quickly volunteered. We were taken to the motor pool and assigned an FJ70 shorty and an FJ75 pickup, both new with plastic still on the seats. I was only vaguely familiar with FJ40s, so the sight of these two vehicles waiting to be driven on a big adventure was very appealing.

We grabbed our gear and weapons, loading them into the pickup. We were delivering a load of explosives, weapons, ammunition, and MREs (meal, ready to eat) to the Chimore base camp. Did we have any permission, permits, or a letter of safe passage? Of course not. We were the DEA and special agents. There were at least two military checkpoints to cross on the route, and our objective was to do our best to get through them. We were also told not to let the army seize any cargo and to top off with gas whenever possible.

The start out of La Paz was uneventful; I was used to New York City traffic, so aggressive driving techniques were nothing new. On bumpy, 100-year-old cobblestone roads, we climbed out of La Paz onto the Altiplano—the effort of driving seemed strenuous at 13,000 feet. We would be on dirt roads that would climb well past 14,000 feet, wind around the Cordillera Real, and then drop to 8,300 feet into Cochabamba.

The rock-covered ground was brown with the occasional flowering plant, the hills covered with terraces and cultivated plots. Rock walls surrounded farms with small herds of sheep and llamas tended by small children. The people here live a harsh existence in the mountains, not much different than they did hundreds of years ago. They cultivate potatoes, corn, quinoa and raise sheep, llamas, and cuy (Guinea pigs). Cuy is the major source of dietary protein; easy to keep and prolific, I found it delicious.

The road was dirt, though we could make good speed until we came upon an overloaded truck or bus. These “cholo” trucks and buses were the primary form of travel for the local people. Both types of vehicles were as overloaded as possible. This type of road could easily gain international fame due to a bus plunging off the edge down hundreds of feet with impressive death tolls. It apparently happened often enough, as evidenced by the number of roadside memorials, mostly on curves.

Many of the curves were blind ones. Local traffic rules dictated that the first vehicle to blow their horn had the right of way. In reality, it was good only in theory, as we had many close calls when encountering oncoming traffic. We hugged the mountain wall so tightly at times that the side mirror scraped the edge. Going the opposite direction, the shoulderless road drops hundreds of feet onto the rocks. Fortunately, the Land Cruisers were a pleasure to drive, feeling rock solid on the narrow dirt roads, with plenty of power—even at this elevation.

The width of the road varied from one-track to just enough room to pass. The trick was to find a section straight and wide enough to pass. Each passing action turned into a game of chicken as there was always an oncoming car.

The trucks had Motorola radios, so Tom and I were able to chat and point out sights of interest and traffic hazards. All this white-knuckle driving was done to the music of Jimmy Buffett and Warren Zevon on the cassette player.

The military checkpoints took a bit of finesse. There was no way we could allow the soldiers to see what was in the back of the pickup or the shorty. Lots of “No entiendo” (I don’t understand), showing our Embassy IDs while saying “Diplomatico,” and finally, offering a gift of a case of MREs would get us on our way.

What goes up must come down, and now comes the descent into Cochabamba Valley. Passing the slow-moving buses and trucks downhill was another harrowing experience, requiring a constant downshifting with our brakes overheating. In contrast to the desolate brown of the mountain, there was green everywhere in the valley. Instructions to the DEA safe house were good, and soon we were parked inside the compound. Time for a steak and some Paceña beer to wash away the road dust.

In Cochabamba, we linked up with the rest of the team and drove to Chimore. The drive is only about 120 miles but takes just over 6 hours. We passed through farm country, passing the Corani Reservoir, a huge body of water which had great memories for me, as we used to spend time there at a family friend’s bungalow, fishing every day.

As the road climbed up into the mountains, the air got cooler. In addition to our two Land Cruisers, our little convoy had grown with an FJ60 and another Land Cruiser pickup truck. The pickups were set up as troop carriers, with folding bench seats along the side of the bed and a cage over the bed as the frame for a canvas roof. Soon we would be driving our Bolivian counterparts on mobile land operations against the traffickers.

After cresting the mountain, the air quickly became hot and humid as we descended into the Infierno Verde. Our first stop was Paracti, a small village built around a police checkpoint at the entrance to the red zone. We dropped the BORTAC agents there, leaving them to train the police in vehicle searches, looking for the precursor chemicals needed to process the coca leaves. At 7,800 feet, it was hot and humid during the day and cold at night. It rained almost every day and was not a pleasant place to be.

There were still several more hours to drive, and the road became narrower and muddy as it wound down the side of the mountains. The 7.50×16 Goodyear mud and snow tires provided excellent traction, the deep lugs cutting through the mud with ease. I wish those tires were still available today.

As with the previous drive, the side of the road was dotted with memorials to the dead. There were also a couple of large scars on the mountain where landslides had occurred. One time, we ended up being stuck in the Chapare for over three weeks after a landslide, as it took that long to clear the road.

Several waterfalls cascaded down the mountain onto the road, splashing the trucks as we drove. We soon came upon the first town, Villa Tunari; people stared at us in surprise as we passed. It’s not a tourist zone, so we were out of place. On the other side of town, we came up the first water crossing, the Río Chipiriri, about 25 yards wide. A tractor was parked on the bank, ready to tow those whose vehicles had gotten stuck or could not make it across.

My experience with off-road driving was a real advantage, and I briefed the other drivers on what to do. Lock the hubs, low range, second gear, and we plunged into the water. The water was slow-moving and only a couple of feet deep. The bottom was rocky; locals had placed rocks to keep vehicles from sinking. We made it across, shifted back into two-wheel drive, and continued along.

We soon came upon another crossing on the same river, wider with the water flowing faster: back into low range and straight in with a steady throttle. Aiming for the tire tracks on the opposite side, I could feel the water pushing the truck, splashing over the bumper.

We all got across, with only one truck momentarily stuck. As we continued, traffic was light, consisting of cholo trucks, buses, and some motorbikes, with no personal vehicles. Before we knew it, there was another river crossing: the Río Chapare, wide with swift-moving water. This time, I made a bow wave as I drove across, small swells of water flowing over the hood. I would later know these river crossings well as we had to cross them daily to get to our area of operations. Sometimes, the water was over the wheel and the headlights underwater, especially noticeable when crossing at night. It seemed these Land Cruisers were unstoppable. We continued our drive and were soon passing through a good-sized town, Shinahota; more on that later.

Another river crossing, and we finally arrived at the gate of the Chimore Base Camp. The police checked our IDs as we pulled in and were greeted by the special forces guys. After introductions, we were shown to our cots in the GP medium tent that would serve as home for the next few months. While squaring away our gear, we were warned to always sleep under the mosquito bars as vampire bats flew around at night. Welcome to the jungle.

We had brought a couple of cases of beer, which we shared while talking about our objectives. The plan was to drive to different areas and search for the pozo labs; we would seize any evidence and intelligence and then destroy everything with fire and explosives.

After the first couple of missions, it was apparent the fleet of new Land Cruiser troop carriers at Base Camphad some condition issues. Many were missing spare tires (sold for money), had bald tires (new tires were sold), were not fueled up (stolen gasoline), missing windshield wipers, etc. Since the vehicles belonged to the US government, we took control of them and started getting them back up to operational order.

Every day, we crossed three rivers on the way to “work.” It was amazing how these Land Cruisers could dive into the rivers and motor across, sometimes with the water up to the hood’s level. On one operation, I was driving the FJ40. As we crossed a river, the water was up to the seat—my feet submerged and my bottom getting wet.

There were no paved roads in the Chapare, so the routes were either very dusty, muddy, or submerged in water. We also crossed bridges made of logs spanning small gullies or streams. The trick was to keep the tires on the top of the logs lest we slip in between and get stuck. We never had a breakdown and only a few flat tires.

One day while driving an empty pickup, I entered the river. As I got in a couple of feet of moving water, the back of the truck started floating. I was soon moving downstream with all the wheels churning up the water like a paddleboat. As the front of the truck hit bottom, I made some forward progress. After several tense minutes, the vehicle was pushed into shallower water, and I made my way along the side of the river to an exit area. Note to team: do not drive empty pickups through the rivers.

Our days consisted of searching for the coca-paste-producing pozos. Traveling the dirt roads, it was easy to detect places where a lot of activity had occurred. We would then follow the path and come upon the pozo. There would be large sacks of coca leaves and cans of chemicals. Established pozos were truly toxic waste dumps. We would destroy everything and go back and look for more. We would also look for men walking on the road with black feet—a residue left from stomping the leaves in the sulfuric acid water mix. In a 12-hour day, we could hit over a half dozen of these labs.

While pozo hunting, we were also looking for high-frequency (HF) radio antennas. All the coordination between the narcos within Bolivia and Colombia was done with HF radios—the cell phone of the time. Possession of an HF radio without a permit was made illegal in an attempt to disrupt command and control. Removal of a radio could knock out operation transport for several days. The coca paste would then build up and was stored in caletas or coves, becoming another mark of ours.

Clandestine airfields were targeted in two ways. First, we developed or obtained intelligence of when an airfield was being used, and then we would infiltrate or “lay in” the airfield and wait for an aircraft. Once the plane landed and was being loaded, we would make our presence noticed (initiate the ambush) and move to disable it, detain the pilot and loaders, and seize the dope. Since there were always Colombians, it never went as smoothly as we wanted. Thankfully, we always prevailed without any casualties. But unfortunately, I can’t say the same for them.

Our other mission was interdiction: getting to the airfields and planting cratering charges. These charges were a simple ammonium nitrate and diesel mixture (ANFO) that we made in camp and packed into sandbags. We would dig 4-foot-deep holes at the airstrip and fill them with a couple of sandbags, some seized dynamite, and a block of TNT. The resulting craters were huge, many times reaching the water table and quickly filling up, making them harder to repair.

As you might guess, we weren’t very popular with the local coca-growing population. It got so bad at times that as we drove through Shinahota, we would have rocks thrown at us and even lighted sticks of dynamite. We went as fast as we could with the windows up, suffocating in the heat and humidity. One time a stick of dynamite landed on the windshield, the fuse sputtering toward the stick. I hit the wipers, knocking it to the ground, where it went off with us laughing nervously. Other towns greeted us in similar fashions. Despite being hit with good-sized rocks, we never had a window broken—another testament to the trucks.

Things got worse after time, and we had to race through towns and push through flimsy roadblocks, cracking open the doors and rolling CS (tear-gas) and smoke grenades out to discourage the rocks and dynamite being thrown.

Each day was an adventure in off-road driving with the river crossings and muddy roads due to the frequent rains. There was a Jeep CJ, full-sized Bronco, and a Bronco II at the camp that were never used other than going to the village to buy beer and chickens. I asked one of the guys, who had been at the camp longer than me, why the vehicles weren’t used on ops. He replied, “They just can’t handle the conditions.”

After 120 days, it was time to go back home. It was going to be a major adjustment from driving Land Cruisers in the Bolivian jungle back to driving a car in NYC traffic.

I was so impressed with the capabilities of these Land Cruisers that I knew I would soon be owning one. My first was a 1985 FJ60, quickly joined by a 1977 FJ40. I now have a 200-Series and would not hesitate to drive that anywhere.

After many tours, a couple of years later, I reported to the DEA office at the US Embassy in Lima, Peru. I was handed the keys to a brand new 1991 FJ80 5-speed manual transmission with level III armoring. But that is another story.

Read more: Evolution of an Icon: The Toyota Land Cruiser

Our No Compromise Clause: We carefully screen all contributors to ensure they are independent and impartial. We never have and never will accept advertorial, and we do not allow advertising to influence our product or destination reviews.