An 11,000-foot descent, sheer drops and 200 plus deaths a year: Welcome to Bolivia’s Road of Death, the terrifying route tourists love to two wheel down. Its official name is Camino a las Yungas but it’s best known as La Carretera de la Muerte, the Road of Death. It’s not just a name either: the gorgeously lush, winding 64-kilometer route that links La Paz with the town of Coroico is still considered by many as one of the deadliest roads in the world. Just one of many in Bolivia.

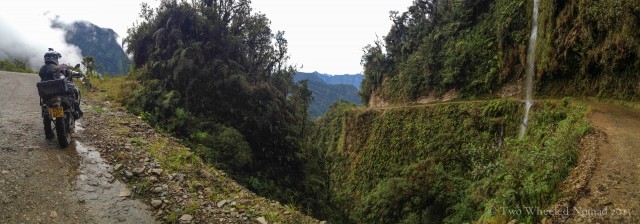

The North Yungas journey is renowned to be overwhelming, as much for the staggering scenery as for the dangerous gravel route. It’s part of the transition zone where the Andes fall away into the Amazon Basin. For the locals, the ‘Death Road’ was an important transport route, which they braved in cars and trucks, teetering on the edge and risking their lives with every trip. The mortality rate is not surprising considering that: safety barriers are few and far between, vehicles meet head on along a miniscule dirt track – at peak altitudes of more than 4,500 meters – and with a vicious drop off on one side of up to 800 meters. No wonder it was deemed ‘The world’s most dangerous road’ by an Inter-American Development Bank report in 1995. On the up side there’s now a much improved, replacement route, which since 2007 tends to all the heavies and commuter traffic with far less incident than before. Still, leaving an old road not to be reckoned with.

Although still in use by the odd local car, tourist minibus and support vehicle, it’s the over-zealous cyclists that come a cropper, more than passing motorized traffic. This is because of kamikaze, freewheeling cycle guides racing down at full tilt for the sheer thrill, substandard mountain bikes on hire to one and all, or a blind unawareness if not overconfidence to any oncoming, upward traffic.

Psyched with a mixed bag feeling of ‘Just how hard is this road going to be?’ deliciously tinged with that pre-excitement you get moments before a rollercoaster’s tipping point. We gave ourselves no choice but to take a deep breath and carefully: navigate around careening cyclists hell bent on fulfilling their bragging rights, falling rocks and blind hairpin bends, penetrate waterfalls, cross two rivers and endure the fog, mud and humidity. All over a 3,600 meter vertical descent.

We knew the trip was set to take in stunning views among the rolling hills, but come with the somewhat distracting – and for some frightening – lofty heights from the canopy as two rubber tires separate the rider from a narrow single-lane road with very little in the way of roadside protection. The ride was set to be adrenaline-packed as it was unforgettable.

Built on the backbreaking labors of Paraguayan prisoners during the Chaco War between Bolivia and Paraguay, the construction of the road took place in the 1930s. Due to both the engineering design of that decade and the natural structure of the area, its topography and geological formation meant steep slopes were created. The resultant single-track lane varied in width from 2.9 to 3.5 meters.

Our starting point in La Paz at 3,600 meters was almost a low point compared to the motorcycle-chugging ascent up to La Cumbre’s cloud forest at 4,650 meters. Along the way on ruta 3 I coaxed Pearl, my motorcycle on a little as she sighed in a sluggish, less responsive manner. ‘It’s alright lady, I’ll keep you in third gear’, I reassured her. We fumbled our way farther on through bike-swallowing fog under grey scraps of cloud, which tossed like leaves in a fitful breeze, shifted, like wind-tossed foliage. The cold wind helped to numb the pangs of hunger but didn’t alleviate that gnaw of anxiety building.

With my helmet visor permanently steamed up, icy rain pellets stung my cheeks as I carefully worked my way up and down the undulations of the road, skirting around deceptively deep potholes. I probably looked like a drunken sailor on two wheels heading toward the next watering hole. When you face the force of foggy rain, you don’t exactly ride boldly forward in a show of unbridled confidence. Bluster will get you battered. Still, the views passing Cotapata National Park took on the supremacy of the Scottish highlands, the delirium of England’s Lake District and then New Zealand’s soul-nourishing hills, towering above us. Bolivia for me just keeps getting better and better.

The entrance to the Death Road started in rarefied air, slightly above the already high-elevation of La Paz. Although not so deadly nowadays, for a few hummingbird heartbeats the realization of making one mistake and you’d meet your maker hit home, but the thought flickered away again. May be the thought of reaching ‘game over’ had been lurking but I hadn’t dared to admit it because then, like the nuclear bomb, it could never be uninvented. Pearl and I would exercise care and become caution personified.

Before biting the bullet onto the road itself, we spotted a pair of 250cc Chinese bikes in a clearing and, perhaps stalling for a little time, headed straight for them. Two Australian guys were also preparing for the thrill ride, getting their gig in order as much mentally as physically. Their jacket-less armor and lightweight machines boasting proper knobbly tires made quite the model ‘Death Road’ ensemble. “Nice bikes, guys!” was the first comment to come from them. “Thanks lads, looking forward to the Death Road?” I enquired. Of course, now lets go do it.

The mix of beauty and danger on the Death Road was intoxicating. The stony dirt track thinned and when it nearly died altogether, grew more confident just as quickly, giving way to a wider track, which led to a stretch so to speak, ridable on road. Without wisdom, imagination is a cruel taskmaster. I observed early on that letting go of any apprehension got us moving much quicker.

Despite the intermittent bounteous rainfall, repeatedly stopping to don and ditch the waterproof onesies, the weight of the world dissolved in the invigorating flashes of the rainbow-spraying waterfalls, the sun on my shoulders and the stillness of the place drawing me in. With the remnants of the cyclists remaining after midday – who waved their fronds and gave way to us – an excitement sang in my veins as I rode along the steep and bumpy track. It seemed the whole world was in my grasp, and it seemed as though I was lifting off above myself; tooling along on my motorcycle and at the same time lifting into the sky, and so filled with elation and freedom that I had to open my mouth and scream.

Jason was itching like a kid on Christmas morning to unwrap the drone from its box and take it for a spin over the near-vertical abyss. The space between the dry highlands’ Altiplano-bound clouds and the steaming, forested depths of the humid lowlands. I guess it’s every filmmaker’s dream to capture the airborne essence of such a dramatic scene. Alas, the pervading air of hard-won tranquility ceased and resulted in a calamity-led crash. Inches away from plummeting over the precipice, the unit dropped towards us like a gannet dive-bombing its prey. That high thin air left little and less for the drone to push against. Hey ho, Jason had still managed to shoot a few microseconds of aerial gold.

Hugging the walls of the sheer valley, we snaked our way beneath rocky overhangs and elongated cascades. It was impossible to ignore the reminders of deaths as we rode past shrines, memorials and crosses that pop up at chillingly frequent intervals. All marking the tragedy of the vast number of lives lost to the road. It humbled me from the inside out.

High in lush elevated jungle, riding through 100-meter high waterfalls, streams and by coca fields was a ride like no other. As I got power-showered through the waterfalls, the terrain became its most rocky. And slippery, washing away part of the road. I rallied. I had better go through with it, Pearl had pride. More than me. It was easier than I’d anticipated, as if I were an oyster already loosened within the shell. I held onto the little thrill this gave me. A needlelike pleasure in my stomach, just below my ribcage.

Close to the road’s connecting town of Coroico – a town that takes its name from the Quechua word coryguayco meaning ‘golden hill’ – we convened at the second river crossing. More rocky than the former river’s pebbly version, the latter was also longer; a 20-meter stream gushing water half way up our wheels as we wended through. Two locals had parked up in a shallower section, utilizing the free resource to clean their cars and themselves. ‘Why not?’ I mused. The water looked fresh and sparkling, pure enough to drink I’d imagine. I staggered across on Pearl, a little jerky as Jason effortlessly glided through showing me how it was done. My textbook river crossing would have to wait.

We survived all the way to the end of the Death Road. Its steep mountains, plunging valleys and rugged terrain. Whoa! It seemed only logical to return the way we came and enjoy the road going back up. Even if it meant meeting the odd unsuspecting cyclist or car coming downhill; as oncoming upward traffic, we supposedly had right of way. Ascending was in fact easier, enjoying the physical and psychologically safer wall of the mountainside on my left. One of the few if not only places in South America that stipulates left-hand side driving.

The afternoon’s momentum maintained in full swing, showers fell on and off until eventually the sky dried and reared up above us, rose and lavender. The reverse journey saw long shadows inch across the dense, bottle green sub-tropical Yungas. There was a light from the sky that gilded the clouds, intensifying the sun lowering every hour. Perched on the precipice was definitely a day to let the world take care of itself, a paradise of thoughtfulness.

The Camino de la Muerte is a legendary road and despite its past innumerable deaths experienced, that moment of adrenaline, suspense to the unknown and exposure to nature, you can feel the fascination and buzz – down and up. Every second that passed the little hairs on the back of my neck rose, whilst my image-tank became full to bursting as emerging and radiant growth unfurled before us. It was a biker’s fantasy with jaw-on-the-floor views, another visceral experience. It left me windblown, mind blown and exhilarated.

You can follow Lisa Morris’ offbeat travel tales at www.twowheelednomad.com