Originally featured in the 2009 Gear Issue of Overland Journal – Few auto manufacturers can lay claim to producing the same model for three straight decades. But that’s exactly what Mercedes-Benz is doing in 2009, with the 30th anniversary of the Gelandewagen—its construction uncompromised, its styling conservative—even severe—but timeless, its configuration adaptable for any situation from a battleground to a Vienna opera house.

The venerable Gelandewagen longs not to be part of current fad, but may well upstage the vehicles that do. Square, modular lines communicate an emphasis on function rather than form, while a comfortable interior make this vehicle an instant old friend. However, it takes more than an enduring design to both remain current and withstand the ever-changing marketing demands, cost-cutting measures, and management disagreements found in modern automotive corporations.

Predecessors

The Mercedes-Benz Gelandewagen, often referred to simply as the Mercedes G or G-Wagen, has found its way into all three major 4WD vehicle sectors: consumer, commercial, and military. This has been key to the G’s continued success as a product of the highest level of quality and performance. The cost of building a vehicle that is 70-percent handmade is staggering in the current economy. However, by adapting quickly, as the vehicle also does to varied terrain, Mercedes has kept the G-Wagen a valuable tool. Just one year into production, the Gelandewagen was being produced in more than 40 different versions. It has become a legend, whether defending the peace or winning multiple Paris-Dakar trophies. Countless successful expeditions have earned the Mercedes G its status as one of the best overland expedition vehicles ever conceived. A strong sense of values, such as an emphasis on safety, quality of build using commercial truck components, and an unmatched balance of performance, allows the G to captivate those fortunate enough to have relied on one as a travel companion. Since 1979, the G has proven itself to be, as described by Ed McCabe in his book Against Gravity – From Paris to Dakar in the World’s Most Dangerous Race, “a proven tank capable of going to hell and back under frightful conditions.”

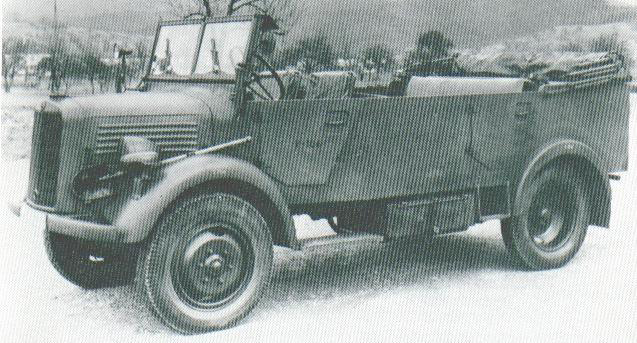

The history of the Gelandewagen is rooted in Karl Benz’s first designs of the world’s premier 4WD and AWD vehicles. Benz developed the first motorcar in 1886, and the first 4WD soon after, although the designs would take more than 20 years to get into production. In 1926, the companies of Karl Benz and Dr. Gottlieb Daimler merged to become Daimler-Benz, and soon after that the 170 series of automobiles was in production, offering a platform upon which to fit out the first production all-wheel-drive and all-wheel-steering vehicles in the world, known as the 170VG and later the 170L.

In 1926, Daimler-Benz introduced the G1, which featured rigid axles, leaf springs, and a pressed-steel frame, and was thus a stouter platform from its inception than the 170-based predecessors. The model designation G originated during the research and development phase, when it was referred to as a “cross-country vehicle,” or “Gelandewagen” in German (this is also the root term for the BMW G/S motorcycle).

The G1 was short-lived, and only six were ever produced. It was used as a prototype for the higher-production G3/G3A, of which more than 2,000 were manufactured between 1929 and 1935, primarily as part of the German war effort. The G3 platform incorporated three axles, one forward and two aft. The G3s, astonishingly, featured locking differentials in both rear axles. Half-track versions were also produced. In 1934, Daimler-Benz released the G4 as a larger, longer version of the G3 series, featuring up to 110 horsepower with three body styles. Followed finally by the G5, the series would see its end once Germany fell to allied forces.

The G5, built as a car version with a production of 606 units and a truck version that totaled 4,900 units, offered some interesting technology as well. The engines were tuned for maximum torque just above idle, to assist crawling through difficult terrain. The first-gear ratio, a staggering 722:1, yielded an impressive 64-percent climbing ability even when burdened by a full load of cargo. Truly the ultimate vintage 4WD, the G5 became the starting point for the legendary Mercedes L-series AWD trucks, produced until just recently and sold in the millions. In the 1950s, the Unimog combined elements of this series with the farming tractors of the day to morph into yet another timeless design. But the G series would not be revived for much longer, and mostly by chance.

A New Beginning

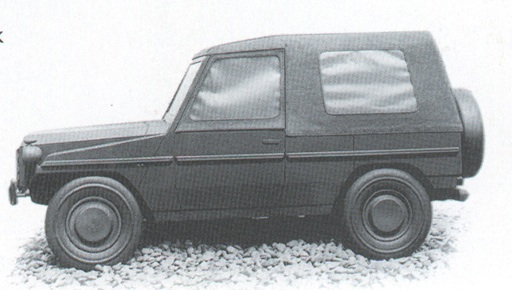

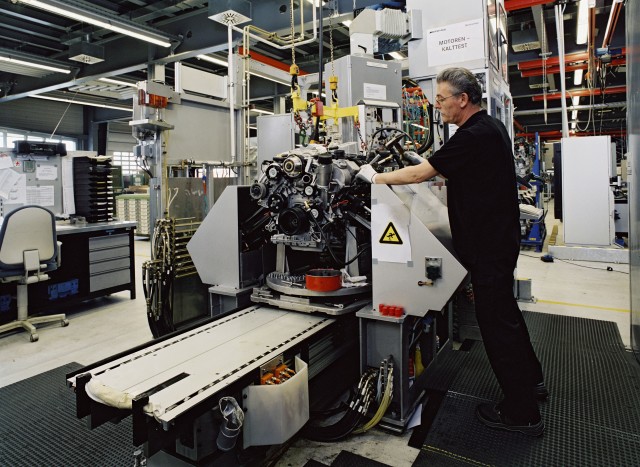

The Gelandewagen was reawakened as a design in 1973, conceived as a commercial- and military-grade vehicle that could also be marketed to consumers. The first production code was H2, once Steyr-Daimler-Puch of Graz, Austria became involved with the project. SDP was chosen after careful review of several potential sub-contractors, including the large commercial European maker MAN and even General Motors. At the time, the SDP production facilities were busy assembling more than 2,000 bicycles and 1,000 motorcycles every day. Four-wheeled vehicles would become SDP’s mainstay business during the 1980s. (The conglomerate was broken up in 1990, and Steyr’s automotive production division sold to Canada’s Magna Industries; it’s now known as Magna Steyr.) The Steyr end of the business had produced a wide variety of products, from firearms to large commercial trucks. That experience was applied directly to the G.

When SDP began to develop what would become the Gelandewagen, they chose the designation H2 because it represented a replacement for the current offering on the same assembly line, a product known as the Steyr-Puch Haflinger. The Haflinger, a tiny but robust 4WD vehicle, had locked in several military contracts over the years. However, few Haflingers made it into consumer hands as new vehicles. Volkswagen’s 183 Iltus had bettered the Haflinger’s minimal bodywork and poor occupant protection, but still left much to be desired in regard to cargo capacity and towing ability. Thus, a new vehicle was sought to meet the needs of a higher-speed and more nimble military. Contract preference seemed to be moving away from the larger and more complicated Pinzgauer, also built in Graz before and during the production of the G model. The G would fill the military requirements and at the same time be more of a consumer-friendly product. Other names were considered initially, but in the end the Gelandewagen was born without a fancy marketing term attached.

An advance 20,000-unit order from the Shah of Iran, the largest shareholder of Mercedes-Benz in the 1970s, got the ball rolling toward production of the first Gelandewagens. After the Shah’s sudden overthrow during the Islamic Revolution of 1979, the order was abruptly cancelled, so Mercedes and Steyr-Daimler-Puch looked to establish contracts with the German Border Patrol. Elsewhere, the Argentine Army was preparing to embark on the ill-fated Falklands campaign, leading to a large order. Later, NATO, as well as the Norwegian, Belgian, and Greek militaries, submitted orders too, viewing the G as a step forward in cargo capacity, personnel safety, and ability to be airlifted directly to and from the battlefield. Similar to other military contract spec-based vehicles, the G can be stacked in a jet cargo plane to maximize use of space. These were, and still are, important concerns for military customers, and the clearly defined symmetry of the G body style stands as testament to the engineers under pressure to comply.

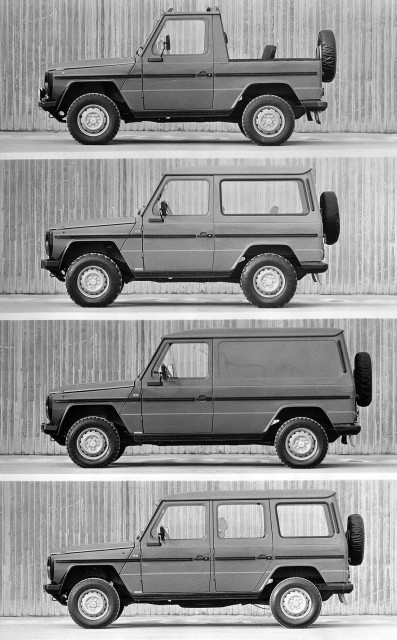

For the civilian market, the 1979 G-Wagen was launched with three body styles. The chassis offered were a short-wheelbase (SWB) two-door hardtop, a SWB convertible pickup, and a long-wheelbase (LWB) five-door wagon. The following year, a van version was added, and an open-chassis truck soon after. Many of the driveline components were sourced from the ranks of Mercedes’ own commercial transport product division; other influences came from the recently acquired Hanomag Company. With the engineers from Mercedes, Hanomag, and SDP all cooperatively working on the H2 project, success was hardly a surprise. By the time the wood models had been turned into clay, followed by a series of different test mules, the resulting production G series featured a unique combination of comfort, on-road performance, safety, and off-road prowess. The vehicle was equally at home traveling the Sahara, crossing boulder fields in the Americas, or cruising on the Autobahn.

Engineering Excellence

Stark differences from previous 4WD vehicles could be found on the first of the G production vehicles. Front and rear differential locks, for instance, were not available on other production vehicles, nor was a transfer case capable of shifting between low and high range while moving. The latter feature meant momentum was not lost in critical situations, such as during a soft sand crossing: The more a vehicle loses forward momentum, the more likely it is to sink or exceed possible traction. If the driver has to stop in the middle of a crossing to shift to low range, he may already be beyond hope of extracting the vehicle. Of course, a seasoned driver will shift the vehicle into low range before entering the difficult stretch, but having the ease of selection on the go is certainly an asset, and even experienced drivers can be caught unaware of changing surface conditions.

Geometry in frame shape, suspension components, and axles was designed with an emphasis on maximum traction and control, but without a loss of driver feel. The center of gravity on the G was kept low with careful placement of components within the boxed steel frame. This allowed for the boxy, utilitarian bodywork, which to the casual observer might appear top-heavy. It truly works, and Mercedes, in 1979, included a 54-percent side slope diagram in brochures. A wider track than many previous SUV-type vehicles—1425mm (56 inches)—also gave the G very stable underpinnings. Approach and departure angles were 36 and 31 degrees respectively, allowing the G to maneuver over large obstacles. Once on an incline, the G could continue climbing a grade of 80 percent. Many different ring and pinion sets were offered, up to 6.17:1, which yields a 98:1 crawl ratio.

Safety had been at the forefront of Mercedes-Benz product design for some time, and during the 1970s, it was becoming one of the company’s most promoted selling points. Crumple-zone engineering had just made incredible strides in the W123 chassis automobiles released in 1977, so in the G it was employed for the first time in an off-road vehicle.

After testing the Land Rover, Range Rover, and other 4WDs, Mercedes engineers made another choice still considered radical at the time: they specified coil springs at all four wheels, rather than conventional leaf springs. The engineers knew that coil springs would improve ride quality dramatically, as well as handling, dampening, and rollover safety. The rear axle received progressive-rate springs that were unique, designed in cooperation with Eibach. The spring rate not only changed in regard to spacing between each coil, but the overall coil diameter changed from top to middle to bottom. This allowed the suspension to act more consistently, even with large differences in cargo load. Many different lengths and spring rates are available, each one color-coded with stripes to indicate length under various loads.

A load-bias control spring, as seen earlier on Mercedes Unimog and L series trucks, was fitted over the solid rear axle, to ensure the best balance in braking under varying load requirements. The spring senses the load differences carried by the vehicle and adjusts the front-to-rear brake bias accordingly. More pressure is sent to the rear of the car for heavier loads and less pressure for light loads or when empty. This allows added rear braking not normally permitted on a static system, because when empty the rear wheels would skid. (One note worth remembering is that when any G is modified with a suspension lift, it is vital to replace this spring with another version from Mercedes.)

Wheel travel with the coil springs was a generous 260mm (10 inches) in order to keep as many tires as possible on the ground in extreme conditions. The axle-load distribution was optimized so that the G would slide slowly sideways when tilted toward its tipping point, allowing the driver to react in time in order to counteract the situation. Chassis flex was minimized with three torsion-resistant cross tubes in the rear, boxed-steel longitudinal frame members, and additional cross tubes in the mid-section as well as the front. All driveline components were mounted to these strong tube frame members with oversize dampening bushings. Drive shafts, axles, even the seemingly unnecessary count of eight bolts for the flanges to the pinions and transfer case, all give an immediate sense of “overbuilt.” Taking apart a G takes quite a bit more time than some of its counterparts in the SUV product set, but many owners see this as a fair trade for not having the car come apart on them while traveling.

Specific wet-weather features such as water-tight doors, breathers on all gearboxes, a high engine air intake with optional snorkel, and hand-sealed bodywork joints are just a few of the design components the G employs to enhance its water-fording ability. Both the electrical system and any engine components that need to remain dry are positioned in a way that allows a 60-cm (23.5-inch) fording depth.

In snow conditions, early G-series cars, known as the W460 models, can have a more difficult time driving safely with their part-time 4WD. Similar to any other part-time system, if only two diagonally opposing drive wheels are receiving torque, a forward-moving vehicle can be at risk of spinning out if the vehicle is downshifted at too high an rpm. Later versions, developed in 1990 and sold presently, are known as the W463 series. The W463 vehicles offer an advanced AWD system that significantly reduces the possibility of spinning on ice.

In the 1970s, car manufacturers were making strides in regards to corrosion protection, and the G was no exception. During production, the body is first degreased, phosphate coated, and then electrophoretically primed. This is done by way of dipping the whole unit into a pool that is electrically charged in order to best migrate the coating particles onto the metal. The bodywork is then treated with an undercoat before being subjected to a baked-on final finish. PVC is then used as an under-sealant, and even the chassis gets its coatings bonded on through a heat process. A zinc-dust compound is placed into areas where road debris may collect. Only once this exhausting process is completed is each body then married to the similarly over-constructed chassis. (Even with all this effort, prospective buyers should be aware of older Gs, which tend to hide rust in the rockers, rear corners, below the windshield, and below the B-pillar on the LWB.)

New Competition

By 1990, the Japanese had launched a formidable set of 4WD products into the global market. Toyota’s rough-and-ready Land Cruiser was redressed in fancier clothes for U.S. customers. In Europe, the Range Rover had bridged the chasm between utility and luxury and was seen as a more comfortable, better-mannered option to the early G. Thus, in the late 1980s, it was thought that the G should be replaced. Many argued, however, that instead of being completely redone, the platform could be updated into a more comfortable road car that retained its proven off-road underpinnings. Mercedes set its eyes on the Range Rover and Land Cruiser 70 Series to see what they needed to improve. In 1990, the new W463 version G vehicles were finally released to a very positive public reaction.

The W463 not only dealt with some of the negative aspects of the previous W460, it also took the whole G experience up a notch. Now the G was equally at home with any other luxury 4WD on the road, giving its owner smooth manners, more power, and comfort accented by orthopedic seating and walnut trim. Airbags were included for passenger safety for the first time in the model range, and larger brakes were also fitted. Additional changes included full-time four wheel drive and ABS. The differential lockers were now switched electronically. The new VG150 transfer case also included center-locking capability, usable in high or low range.

One oddity on the W460 series was that the transfer case reversed the direction of drive for the front axle, adding unnecessary complexity to the system. The W460 also suffered from driveline angles greater than optimal. Over the long term, many W460 owners experience driveshaft u-joint failure and vibrations because of these angles. SWB models have an even worse angle in the rear with their shorter shafts, which without major modification also limits suspension lift to about three inches. Both the reverse-direction front drive and the excessive driveline angles were corrected on the W463 models.

The new W463 introduced upmarket upholsteries and carpeting, and although this was a hit with the non-adventure types, many overlanders prefer the older spartan interior, which could be easily sponged clean, and the mat flooring that featured 1.5-inch-thick foam padding similar to a sleeping pad. On the other hand, the early vehicles have a heavy folding bench seat that, while removable, is a cumbersome 145 pounds. The newer W463 cars have split folding rear seats that are easily removable with pins. Either model in LWB form can accommodate a six-foot-three owner and partner or furry friend sleeping in the back. Most adventurers will remove the rear seats entirely, creating a van-like interior that can be used for hauling massive amounts of cargo (well secured with plenty of tie-down D-rings) or as a comfortable sleeping cabin. Gunther Holtorf recently completed a series of trips totaling more than 600,000 km (370,000 miles) in his 88hp 300GD, and kept 450 items on inventory in the car, the heaviest being a pair of shocks. He still had room to sleep the car almost every night of his journeys.

The American Market

Nearing the end of the century, Mercedes was again looking at the G in regards to replacement rather than refinement. Some large contracts were cancelled, and it seemed that the Graz production line might need to be backfilled to keep things going. It was at this time that exporting the G to the United States was not simply considered, but pushed. For many years, Mercedes corporate in Germany had wanted to sell the G in the U.S., but the North America marketing teams did not see a fit for the vehicle, since it did not resemble the modern sedan and coupe designs they were advertising and thus was thought to detract from the product positioning of the time.

For many years, a New Mexico business called Europa had an agreement to import a limited number of G vehicles specially converted to USDOT specs. Due to the exclusive arrangement, Europa was able to charge a premium, sometimes exceeding $135,000 when fully optioned. This restricted the U.S. G-Wagen to the very wealthy. The profit on these sales was large but the volume was low—the same vehicle sold around the globe for about half the price demanded by the New Mexico importer. About 1,000 Gs were imported before 2002, when Mercedes finally settled legally with the owner of Europa and began to sell the car in its own dealers. When this was accomplished, Magna Steyr production filled the void, and Mercedes gave the G a new lease on life.

Once Mercedes began offering the G500 in the U.S. in 2002, with a base price of $72,000, values of used Europa and other grey-market G-Wagens instantly dropped. The two exceptions were the diesels and convertibles, neither of which has been imported by MBUSA. Due to their rarity, these models still retain high value, sometimes double that of the standard five-door petrol vehicles.

The modern 2002 through 2008 G500, and the 2009 G550, offer much the same solid engineering as the previous G cars, but for serious overlanding use the cars have also been somewhat overdone. Much new technology, such as BAS (brake assist), ESP (electronic stability program), ETS (electronic traction support), and ABS, have been added. While these systems do improve safety for the driver in certain situations, they do not improve all situations. ETS works to control traction using the braking system under 6 kph in high range and under 3 kph in low range. Coupled with the advanced torque converter, it is very hard to spin the wheels from a start. ESP manages wheel spin at higher speeds by pulsing the brake of the spinning wheel and moderating engine power. BAS dramatically boosts braking force by employing additional vacuum pressure from the booster circuit when the system senses panic-braking inputs.

Owners frequently complain that there should be a way to turn these systems on and off, but Mercedes has not offered this. You can turn the systems off only by switching on the center differential lock in the transfer case. There is an ESP delete button on the console, but it works only up to 35mph. The only way to drive these cars without these systems taking over when wheel spin is detected is to drive with two feet, rally style, where you can ever so slightly ride the brake pedal into turns, thus deleting the ESP intervention. The way these systems are interconnected does not always make the best sense either. There are about 26 sensors in the car, and multiple “PROM boxes,” or small computer-chip boxes. The main computer sends messages out to these boxes to gather information about the conditions, the way the vehicle is handling, if there is wheel spin, if the yaw is too great an angle, and so forth. The problem is that the computer seems to send out the message to every box in an order, and if one box does not answer back, the system may find an error. Sometimes the error will mean nothing, sometimes the system will not complete its attempt to communicate to the appropriate PROM, and in rare instances the car may shut down all together.

Older Gs have the field serviceability that one would desire for long overland trips into remote territories. Diesel variants in particular can usually be repaired with the most basic tools. Modern vehicles, however, require special toolsets, computers with fancy Mercedes diagnostic software, and hard-to-find parts. For the early cars, master cylinder rebuild kits, axle seals, a shock, or driveshaft end, might be the only special items one need carry. With later models, especially those built after 2001, items such as the crank position sensor, K40 relay, alternator, and various tools to install these items should also be added to the travel kit. For instance, you might feel safe with a spare crank position sensor in your glove box, but if you don’t also have an 18mm extension on a 1/4-inch drive ratchet with a knuckle at the bottom and #8 Torx socket, you’re still sitting in a non-runner. These types of unique situations are all documented on various discussion forums and club sites, so obtaining the list and securing the parts/tools is all that is needed before venturing off. Taking printed versions, or at least PDF files, of service manuals is also a clever move for those keen on leaving civilization.

Sometimes “improvements” and added features take away from the design philosophy that brought the product’s initial success. In the G’s case, it was the original simplicity and field serviceability that was lost in the fray of modern marketing. Fret not: the modern G still retains most of the truly important features of the original design, and can be relied upon as a stalwart, trusty steed that will get you to your destination and back in great comfort. After all, the modern G’s climate-control system keeps the cabin pleasant whether it’s -14 degrees F or + 118 degrees F outside, and heated seats might be welcome during a winter trip near the Arctic Circle. (Although some might find those seats a bit flat in the bottom. Recaro and Porsche seats fit the G just great and can be looked upon as easy-to-install upgrades.)

The W463 lost a bit of the all-terrain ability of the early cars, with approach and departure angles reduced to 36 and 29 percent. In other areas, the model was bettered, and has retained its 80-percent grade-climbing ability and 54-percent side slope capability. With its new advanced torque converter, the G now has a 180-percent increase in startup torque, allowing slow pull-away and smooth transmission of power. The enhanced traction is startling when compared to the older automatics. A new 25-gallon (95-liter) ABS fuel tank replaced the previous steel versions, which could leak if hit on the trail.

Buying Your Own

The final question in regard to these great vehicles is: Are they affordable? It took a while to depreciate $130,000 when stock markets were high and G availability was low. After the release of the 2002 G500 by MBUSA, for $72,000, we found ourselves in another league, where the vehicle is no longer such a rarity. A search on clubgwagen.com, a global G club website, shows many older and newer varieties for sale, with caveat for the previously mentioned diesel and convertible cars. Sites such as autotrader.com, mobile.de, and cars.com show hundreds of available G500 cars. With the valuation of a 2002 model G almost below the $25,000 mark, it will be no surprise to start seeing more interest in it as an overland vehicle.

With depreciation mostly absorbed, the early MBUSA cars may just rise in demand for a new audience—one that will take it off tarmac. The hot-rodded G55 AMG version is not recommended for those interested in backcountry use; its suspension lacks ground clearance, and is too stiff and the rebound too sharp. Repairing AMG motors requires special training, so if you break down in a rural area lacking a Mercedes repair shop employing qualified AMG-trained techs, you are out of luck. Lastly, the massive torque has led to transfer case and u-joint failures, decreasing longevity. The base model G500 needs just the running boards removed to gain rocker clearance, and the 18-inch wheels replaced with the 16-inch wheels previously fitted to the 463 series. Other than these two easy changes, the G500 is an out-of-the-box, ready-to-go overlander that can compete evenly with highly modified trucks. The G likes playing the part of duality so much that it barely seems to get dirty on the trail, helped by the massive ABS plastic fender inserts, mud guards, and a smart flare design that funnels tire debris back down to the ground.

Gelandewagen enthusiasts see the purity and harmonic balance between nature and driver as reason enough to choose the G for travel. The G not only brings its occupants home, it even goes so far as to provide inexplicable Zen-like experiences along the way. Recently I asked 4WD guru and guide Harald Peitschmann why he would choose the G from his diverse stable of vehicles for any long expedition. He replied with one simple answer: “Without having to worry about breaking down or becoming stranded, adventure travel becomes more enjoyable.” The 30th anniversary of the Gelandewagen brings hope that vehicles can still be made with little compromise if they are properly executed and managed right from the start. It also means that those of us without $135,000 can finally purchase a reasonably priced Gelandewagen and start using it as it was intended—to explore!