Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in Overland Journal, Gear Guide 2019.

It’s springtime in Morocco’s High Atlas mountains. The wildflowers are out, birds cheep, and there’s a soft warmth in the air. My flying visit here is capping off a satisfying bout of winter travel in North Africa. A few weeks prior, I’d joined a French trekking group and TV crew exploring Mauritania’s Adrar Plateau. An unseasonal heat wave had seen our caravan on the move before dawn and then sitting out the midday chaleur for up to six hours. And a month earlier I’d returned to the Algerian Sahara for a fortnight of epic desert biking through the winding canyons and pristine sand sheets of Tassili n’Ajjer National Park.

But today it was only Morocco, the sort of place you can visit at short notice with just hand baggage. Joining me were Simon, an experienced overland driver, trials protégé, and mechanic with whom I’d just ridden in Algeria, and Karim, an old acquaintance who’d ridden and rallied big XTs and XRs right across North Africa, from Mauritania to Libya and Egypt.

Both Karim and I had enjoyed the golden era of independent adventuring in the Sahara when you could roam the sands as far as you dared. One time in Mauritania, Karim pushed his luck a little too far, setting off to ride the desolate 500-mile Dahr Tîchît piste alone. It was an adventure from which he’d barely escaped with his life. Since that time, an unfinished wave of insurgencies, failed revolutions, and associated lawlessness has swept across much of the Sahara and desert travel as we knew it has collapsed.

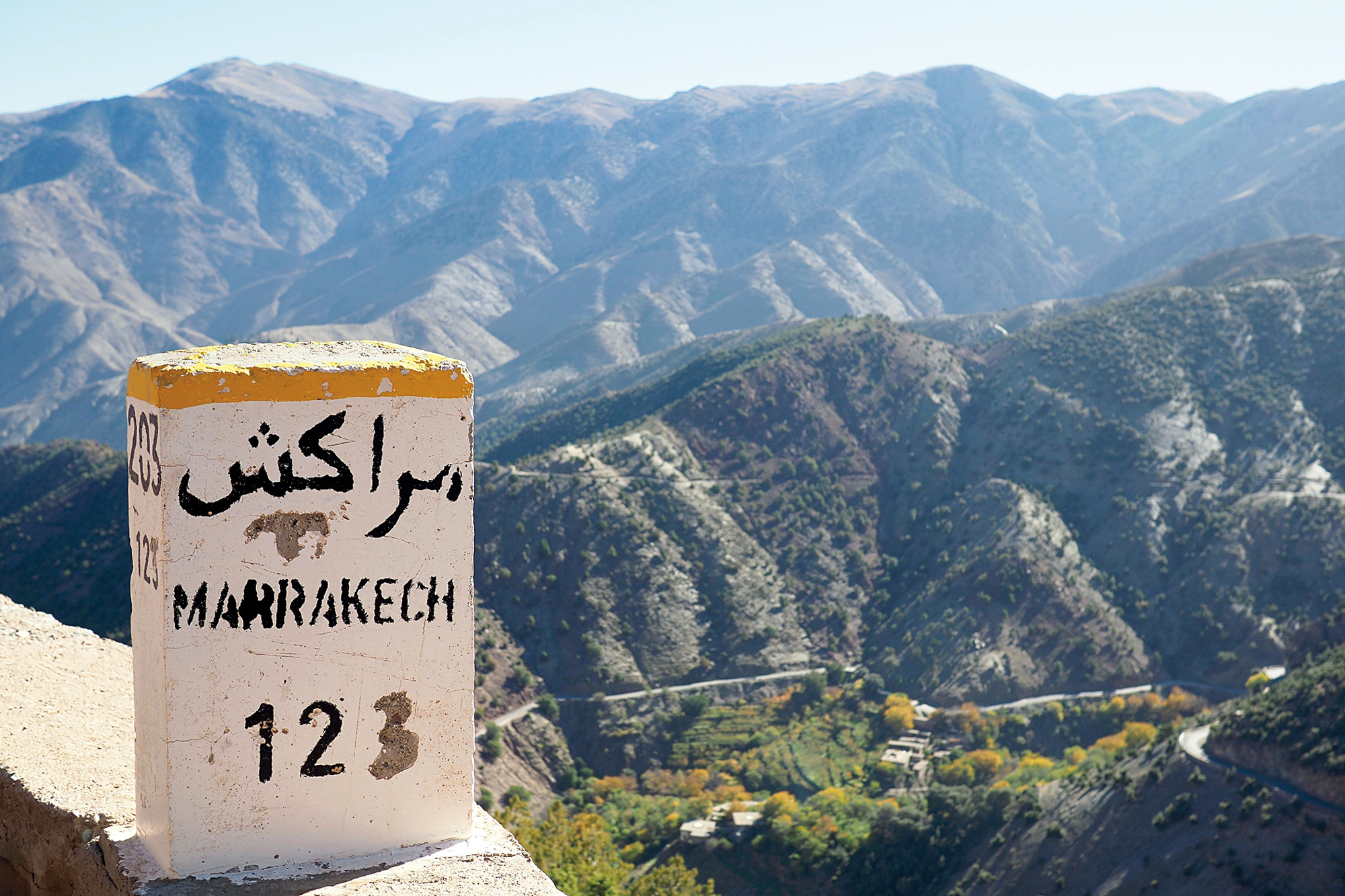

Only Morocco has escaped disruption, and for the past few seasons, I’ve been running small-group, fly-in tours in the south, using a Marrakech rental agency’s resilient Honda XR 250 Tornados. After seven hard years, many have clocked over 50,000 miles—and that’s African rental miles which work like dog years out there. No longer produced, the agency had just replaced them with BMW’s new G310GS. Our mission was to assess this bike along with an old XR while logging new routes in the High Atlas, then nip down through the adjacent Anti-Atlas range to the edge of the Sahara, not far from the Algerian border.

The only large-scale paper mapping for Morocco is now a half-century old, and today, more than anywhere else in North Africa, improved or new roads and huge dams have rendered these maps obsolete. Of course, today’s free, high-resolution online aerial imagery has accelerated that obsolescence and works particularly well in the cloud-free fringes of the Sahara when plotting obscure backcountry routes. But you still can’t beat a paper map in hand to give you the big picture, so at home, I roughly transposed the relevant network of trails from Google Maps onto a sheet of wrapping paper. As I’ve found before, just the act of doing this helps clarify what lies ahead.

With the paperwork done, we left hot and muggy Marrakech around lunchtime, me astride a pristine 310 fresh out of the crate. New though they were, the agency had thoughtfully made some pre-emptive off-road modifications: sump guard, crash bars, and hand guards to protect their new fleet. They’d even gone to the effort of fitting spoked wheels from a G650GS which meant reverting to innertubes, the latter being a retrograde step in my opinion. The benefits of supposedly lighter and “repairable” wire wheels over cast rims are long outdated for anything short of rallying, while easily plugged tubeless tires are a no-brainer on a travel bike.

To the south, an icing of snow lay across the crest of the distant Atlas Mountains. An 80-mile ride led to the 6,860-foot Tizi-n-Test Pass, the less busy and more impressive of the two roads which cross the High Atlas. Soon we found ourselves swinging from left to right above the glittering teal surface of the lake behind Ouirgane Dam, now brimming with winter’s rains.

At around 4,000 feet, just past the village of Ijoukak, a fertile basin spread across the upper valley below the final haul to the pass. Here villagers cultivate the terraces and orchards from whose midst rose the 12th-century ruins of Tinmal Mosque, one of the oldest in the land. A millennium ago, the Berber Almohad dynasty had formed in this very valley, going on to briefly wrest the new city of Marrakech and Andalusian Spain from declining Arab caliphates and other rivals, themselves harangued by the legendary mercenary El Cid.

In Morocco, if not all of North Africa, this distinction between Arabs and the indigenous Berbers (or Amazigh) is not something most casual tourists notice, but is as significant as say, an Englishman in Ireland or Scotland. In the larger towns and cities of the north the difference isn’t apparent, blurred by centuries of intermarriage, as it is anywhere in the urban world. But in more traditional rural regions, especially the villages of the Atlas Mountains, there’s been a revival of Berber identity, struggling against centuries of discrimination from the still-dominant Arab occupiers. Saint Augustine and at least three early popes were Berbers from Numidia, as North Africa was then known.

As we’d all been up since 4:00 a.m., these finer points of Moroccan ethnography were far from our weary minds. Just up the road, I pulled in at the Dar El Mouahidines, one of my regular overnight stops whose name proudly evokes their illustrious medieval forebears. Unfortunately, Mohammed and his son were refurbishing but recommended another family-run place back down the road. In southern Morocco, there are many more inexpensive lodgings than people to fill them. Give your hosts a couple of hours, and they’ll happily lay on a steaming chicken tajine stew, with all the ingredients sourced from an adjacent garden, instead of flown in from the other side of the continent.

“Today is going to be a good day,” I confided to Karim’s handheld GoPro the following morning. And so it would prove to be. Our plan was to leave the Tizi-n- Test road before the pass and locate a parallel but little-used trail that also crested the High Atlas. Unsure of how things might pan out, and with the BMWs’ fuel range as yet unknown, we topped up in the village then set off southeast up a side valley lit by the streaming morning sun. Presently, the road dipped down to cross a stream, and alongside a promising sign a rocky track spun off steeply up the hillside.

In the mountains of Morocco, you’ll find two types of tracks: those still regularly used by locals, and many others which, for whatever reason, have been abandoned and are slowly merging back into the dirt. Without foreknowledge you never really know what you’ll get: it could be glistening new tarmac or a storm-trashed trail of baby heads, landslides, and ditches. Researching routes on a Yamaha WR250R for my Morocco Overland guidebook last year, I’d encountered plenty of the latter, some manageable on the agile steed, while on others it was safer to turn back unless I wanted to go full Rubicon.

With the untried and portly BMWs, I was hoping for the former, but to be on the safe side, excused myself onto the agile XR with the lame pretext that I needed to get good shots of the other two fellows getting gnarly on the 310s. I’ve done hundreds of miles off-pavement on these Brazilian-built Tornados, a lightweight synthesis of aircooled 1980’s technology that makes an ideal African rental hack. That is until you reach 6,000 feet, at which point the ageing XR’s carb can’t decide if it’s choking or surging. Meanwhile, with cooling fans whirring away, the injected 310s climbed steadily from rock to rut. As we approached the 7,200-foot Tizin- Oulaoun Pass, a couple of locals bounced past on a Chinese 125cc motorbike, and just over the crest, a village minivan trundled by, confirming that even this high route was still in the game.

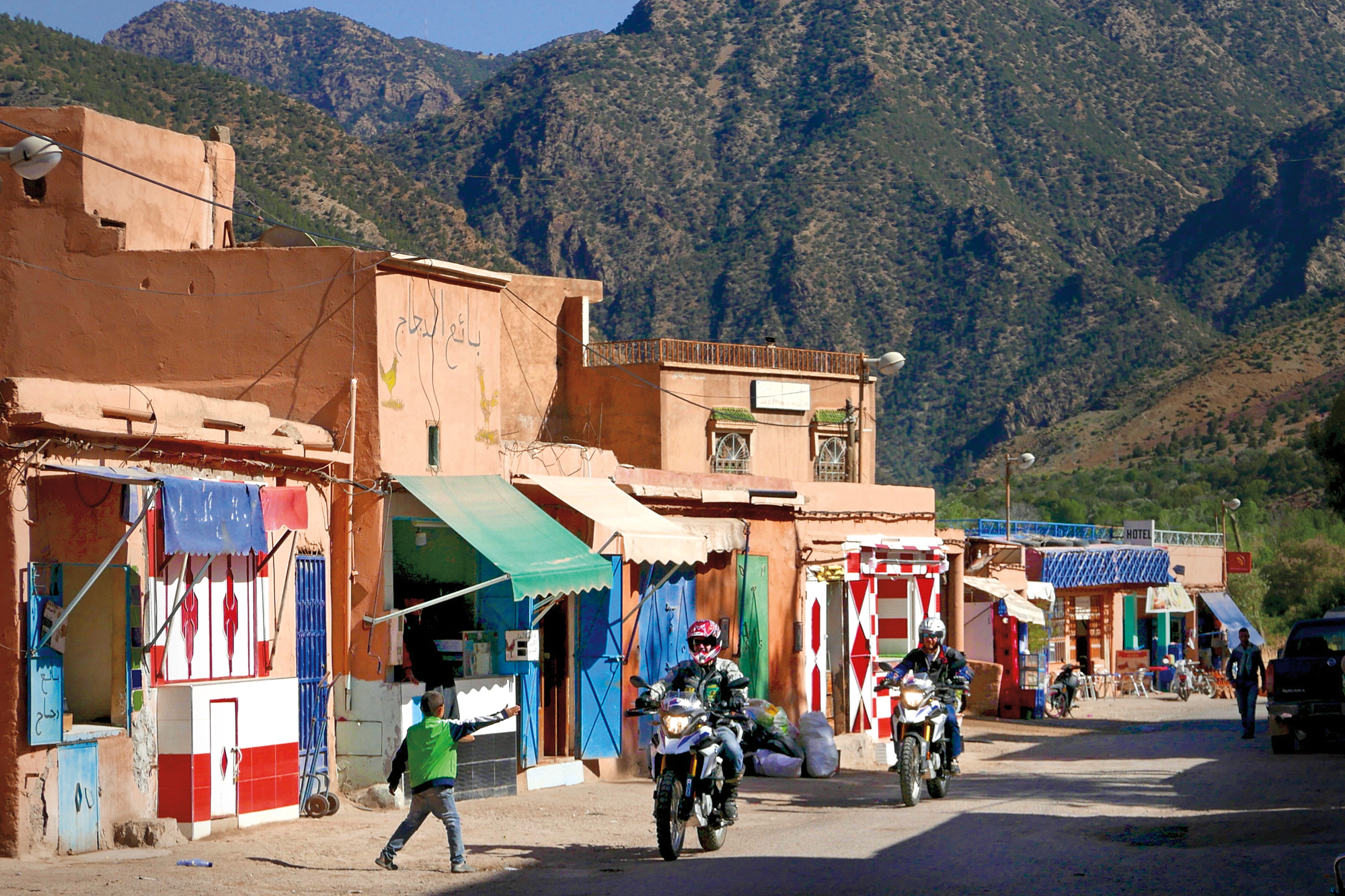

So far, my Google-guesstimated navigation was going to plan, and down in the valley, we joined a newly built road from which they were still brushing away the loose gravel. We passed another cluster of villages spread across a rim-rocked basin, and at a landmark, I memorised an odometer reading for an upcoming turn-off back onto the dirt. Once there, I checked with a villager that the unlikely looking trail did indeed lead somewhere useful, then we crossed a stream bed and bashed our way up the valley, eventually reaching a terrace perched high above the valley floor. But as is often the case riding bikes, the only chance to appreciate the majestic panorama below was when we pulled over for a breather. At any other time, even the nimble XR required steady hand-eye coordination to steer clear of the thought-provoking abyss. An hour or two later with the new route logged, we were back on the main highway, gunning our way east for a quick lunch stop at Assâki. Unlike touristy Taliouîne just up the road, Assâki is just a regular town where you can walk around unnoticed. Even then, many tourists would have passed on the random streetside café we chose, but the bill here for a good feed and coffee came in at just $3 a head. As in many such places around the world, it underlines the dependable benefits of shunning the tourist trail. Those places will always prosper, but take a chance elsewhere, and you’ll find normal prices and a genuine welcome.

After lunch, we fuelled up on the far side of Taliouîne. The new BMWs were returning a comfortable 73 mpg, some 20 percent better than the battle-weary XR. With no fuel until we came back this way tomorrow, 140 miles later, it looked like the XR might have to coast the last few hills. The 310’s mileage sounds impressive until you realise we were riding them well below 60 mph. I bet my Yamaha XSR700 would be nearly as frugal at the same speed. Modest power is, of course, the compromise when travelling on small motorcycles, except they don’t usually weigh 370 pounds. But just as with the full-size R1200GS, once on the move, this GS feels lighter than it is.

We were now following one of my set tour routes to the oasis of Assaragh, tucked above a dry waterfall at the head of a palm-filled canyon deep in the Anti-Atlas. The small groups I bring here are routinely enchanted by the stunning setting of our convivial Berber homestay—not least because some first-time off-roaders find the 20-mile trail into Assaragh a bit of a shock. Recognising that fact, this was one piste I needed to evaluate on a GS for myself, so Karim bombed off on the XR while Simon and I pushed along at the limits of the 310’s suspension.

Geologically older than the High Atlas, the Anti-Atlas is a dramatic series of crumpled escarpments and arid plateaus that drop like fallen dominoes to the Saharan peneplain. Whether exploring it along a serpentine road or a rock-strewn trail, it’s exhilarating to descend from the cool evergreen mountain pines to the rustling palm groves of the desert. As in California, in just a few hours you can pass from sub-alpine snows to baking desert salt flats.

The three of us rattled up over scrawny watersheds and down through dusty hamlets seemingly populated by only kids and old folk. With daylight to spare, we pulled in at the Assaragh lodge, checked over the BMWs for anything loose or broken, then kicked back on the terrace overlooking the canyon and discussed our verdicts over tea, biscuits, and dates. We agreed the GS was pretty good for what it was, but the dual-sport Tornado was more our kind of bike.

The next morning, with just 12 hours to return to Marrakech and catch our plane, we set off early and headlong into one of the highlights of this ride: a spectacular, vertigo-inducing descent coiling down alongside a dry tufa cascade. We passed a new bitumen road creeping towards the remote outpost of Assaragh, but for the moment, the only way to get there was either the way we’d come from Taliouîne, or up this clutch-frying climb. As the track levelled off down below, it skipped over a ford where women kneaded laundry in soapy rockpools, before burrowing through a dense palm grove and emerging into a broad gorge, passing the derelict mud-brick ksars of adjacent ancient villages. For me, it embodies the essence of southern Morocco: enigmatic medieval ruins where the mountains meet the desert.

Now out on the desert plain, we stopped for a tea break at Akka Ighern, the last town before the heavily patrolled Algerian border. As in other places, local kids and grown men gathered round the flashy GSs, ignoring the humble XR donkey. Out of Akka, a herd of camels was being led out in search of grazing while we swung back north into the ranges, me now nursing the XR’s throttle to avoid time-consuming delays if it ran dry. We made Taliouîne with just a cup or two in the Honda’s tank, wolfed down another $3 lunch, then got stuck in the countless bends leading up to the Tizi-n-Test from the south side. A saddle-sore finale brought us back to Marrakech with a sweaty dash to the airport, capping off a couple of action-packed days exploring the wonders of southern Morocco.