“Forget about it. We just came from there. The bridge is gone. Repairs are going to take weeks.”

Two Dutch motorcyclists, Bart and Renate, on their way from Ecuador to Ushuaia, gave us the news. We met them in Huanchaco, a beach town in Peru, one of those places where travelers intend to stay for a day or two but end up lingering for weeks, if not months. The beach, the surfing, the vibes, the pisco sours—or a combination of all of them—are too enticing. However, after weeks of beach camping the moment had come to move on. Peru’s last corner was waiting: its north Andean section, which we were told was stunning in terms of driving as well as sightseeing.

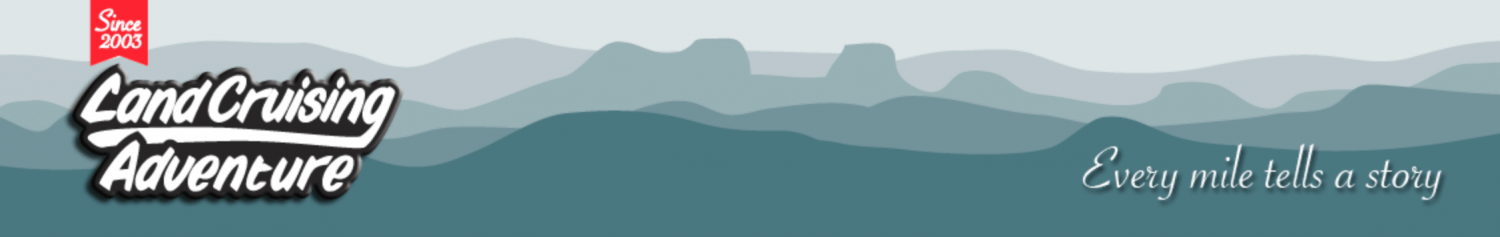

The news was a bummer, but then, isn’t improvising and going with the flow a big part of overlanding? We took out the map and rerouted our journey. We drove north to Ecuador, visited a part of the Andean Mountains, and after our Ecuador visa had run out three months later, headed south for Peru once more, fully confident the bridge would have been fixed. After an easy border crossing at San Ignacio (we just had to wake up the sleeping guards) we meandered in and out of patches of mist drifting among the green mountains. While the scenery was idyllic, the road surface wasn’t; after days of rain it had been transformed into mud. I activated the hubs, and we drove in low gear to prevent the Land Cruiser from fishtailing either into the mountainside on our right or down the vertical drop on our left.

In Jaen, we stocked up on mangos and chirimoyas, our favorite fruits, and drove on to El Almendral Baños Termales. In Peru’s mountains, you will find many natural hot baths with healing properties thanks to the country’s subterranean volcanic activity. Visiting these baths will often cost just a few pesos. The friendly family at El Almendral consisted of eight brothers and sisters, each with families. They lived all over Peru and took turns managing the thermal baths. “If we don’t, the terrain will be stolen by homeless people,” they explained. There was no house and each night they set up their tent under a lean-to.

Soldiers and Officers

On our first day we saw that the scenery was indeed extraordinary. One moment we were driving through valleys covered with a tapestry of green rice fields, and the next we were meandering through a canyon with a brown river thundering between almost vertical rock walls covered in vegetation. We reached an area covered in grass and scrub where a road sign informed us of a desvio (detour). The asphalt disappeared, and we bounced over an unpaved surface. Around a corner, we ran into some guys in black T-shirts.

“We are soldiers from the Seguridad, ” one announced, pointing to the word written on his cap, and added that they were there for our security so we wouldn’t get robbed.

Wasn’t that the nicest gesture? Except for the fact that they weren’t military at all, as Coen was quick to point out to them.

“Yes, we are.”

“No, you are not. You run a private enterprise.”

“Yes. Well, we WERE military but are here for your safety.”

We understood the unspoken request for a fee and paid a Peruvian sole. Some things are just not worth arguing about, especially in the middle of nowhere with guys holding guns.

Back on asphalt, we were stopped at a police checkpoint. Three officers stood alongside the road looking way too serious, but leave it to Coen to deal with police officers (read about our tips for dealing with foreign police and military here). He parked the Land Cruiser in the middle of the road so he was deliberately blocking any traffic and introduced himself. One of them asked where we were going.

“El Cielo (Heaven),” Coen answered with a poker face. “Aren’t we all?”

Not for the first time I wondered how he managed to come up with these witty remarks. It made the men smile. I saw the tension falling away, and they walked around the Land Cruiser, no longer looking for trouble but in admiration. Within minutes we were told to move on.

Cana and Apple Pie

Alongside the road stood a family farm. Two kids were walking behind two oxen in grey slimy mud, herding them around a sugarcane press. Apart from their T-shirts and pants, nothing in this image belonged to the 21st century. An older man, we assumed the grandfather, shuffled down a hill carrying freshly cut sugar cane, which the father subsequently fed to the press. We asked if they sold sugarcane juice.

“Yes, in the barn,” the man replied.

Inside the adobe walls a barrel was being filled up with the juice that was flowing from the press through a tube. With a thick, grayish layer of foam it didn’t look particularly appetizing, but we bought a bottle anyway to give a bit of support to this clearly poor family.

The mother appeared from the back, her face marked by a tough life, including a huge, fresh burn on her cheek, and told us they sold cana as well. To get the sugarcane liquor into a plastic bottle, she needed to tilt a 150-liter barrel. It was too heavy for her, but she didn’t ask the men outside to help her and struggled on. Coen offered to help and together they filled two bottles, for which she asked a mere 50 cents. With prices this low no wonder that farmers like these continue to barely survive at subsistence level.

Peru regularly suffers from earthquakes. Over time, many settlements and cities have been destroyed by them, particularly in the Andes, and many lives have been lost. Thus far, the town of Chachapoyas has escaped this fate and remained a beautiful town still characterized by white-plastered, colonial-style houses with wooden balconies and doors. The municipality forbids screaming signboards, and shop signs consist of black letters written on white-plastered walls or wooden doors, adding to the atmosphere. Rains had been drumming down, and we don’t care for driving in the rain because we tend to drive on, missing out on otherwise nice views or places of (potential) interest. Additionally, our Land Cruiser has leakage problems that are aggravated when we are driving. The Fusion Cafe made up for that miserable weather, serving excellent coffee and the best apple pie we have ever had in South America. The disparity in wealth within a few kilometers wasn’t lost on us, and we realized—as we do so often on our journey—what privileged lives we live.

Kids and Culture

Peru’s north Andean region is rich in historic and cultural sights, one of them being near Karaija. We registered at the entrance of the village and children told us to park under the trees in the middle of a grassy field. They added they would watch the Land Cruiser for us. Coen warned them that no harm should be done to the vehicle; if anyone were to open it, the car would explode. The younger kids looked at each other, not sure what to make of this, while the older ones smiled.

The trail alongside the potato fields was in a bad state, and harvested potatoes were carried up to the road by horses: two bags per horse, each weighing 25 kilograms. On the road stood a truck at the ready, which would load 200 bags of potatoes before driving to the city. The whole community was working on harvesting the tubers that were cultivated on fields shared with rows of yellow flowering mostaza which is made into a paste and used as a skin remedy.

One of the children walked down the ravine with us. Aberdeen was 5 years old and easily walked the uneven trail on flip-flops, offering me a beautiful stone and a couple of flowers. At the bottom, he pointed at a niche in a cliff that once served as a burial site. A handful of sarcophagi shaped like human figures, decorated with white lime, red ochre, and charcoal stood on a sort of ledge. They are about 1,000 years old and used to contain mummies. Because of their close-to-impossible-to-reach location, they have escaped being looted, and overhanging cliffs have protected them from the elements.

On our way back we were met by the kids who informed us the Land Cruiser had exploded. We all laughed.

A Bridge and a Loop?

We merrily weaved our way through this part of Peru along landscapes dotted with historic and cultural treasures and home to the friendliest people in the country. We climbed mountains in the remotest of locations to search for other sarcophagi—which we found. We admired the old mountaintop fortress ruins of Kuelap and studied the cultural finds in the museum of Leymebamba. If you think Peru has nothing else to offer than Inca history and you want to see something different, visit this part of the country.

We had driven a large part of the route to Cajamarca when, once more, the heavy rain spoiled things: a bridge had collapsed. We had no clue whether this was the same bridge as the one of a few months ago or another one, but it was clear that we were not meant to drive “the Loop” of north Peru (as overlanders call this route). However, Cajamarca was on our list for an important reason: the best ice cream of Peru is made there, or so many claim.

What do you do when a bridge collapses? Well, you take out your map and study alternatives. This time we turned around, drove all the way back to El Almendral and farther down along the Rio Chamaya. On our map, a white line south indicated a route to Cajamarca, white indicating a narrow interior road or path. Mix unpaved surfaces and rain and you will get mud, and we got our fair share of it. We plugged away for hours on end, fishtailing our way down. The rain obliterated any views apart from a goldmine, which was too intimidatingly vast to be missed no matter how bad the weather.

Ice Cream Made By Deaf People

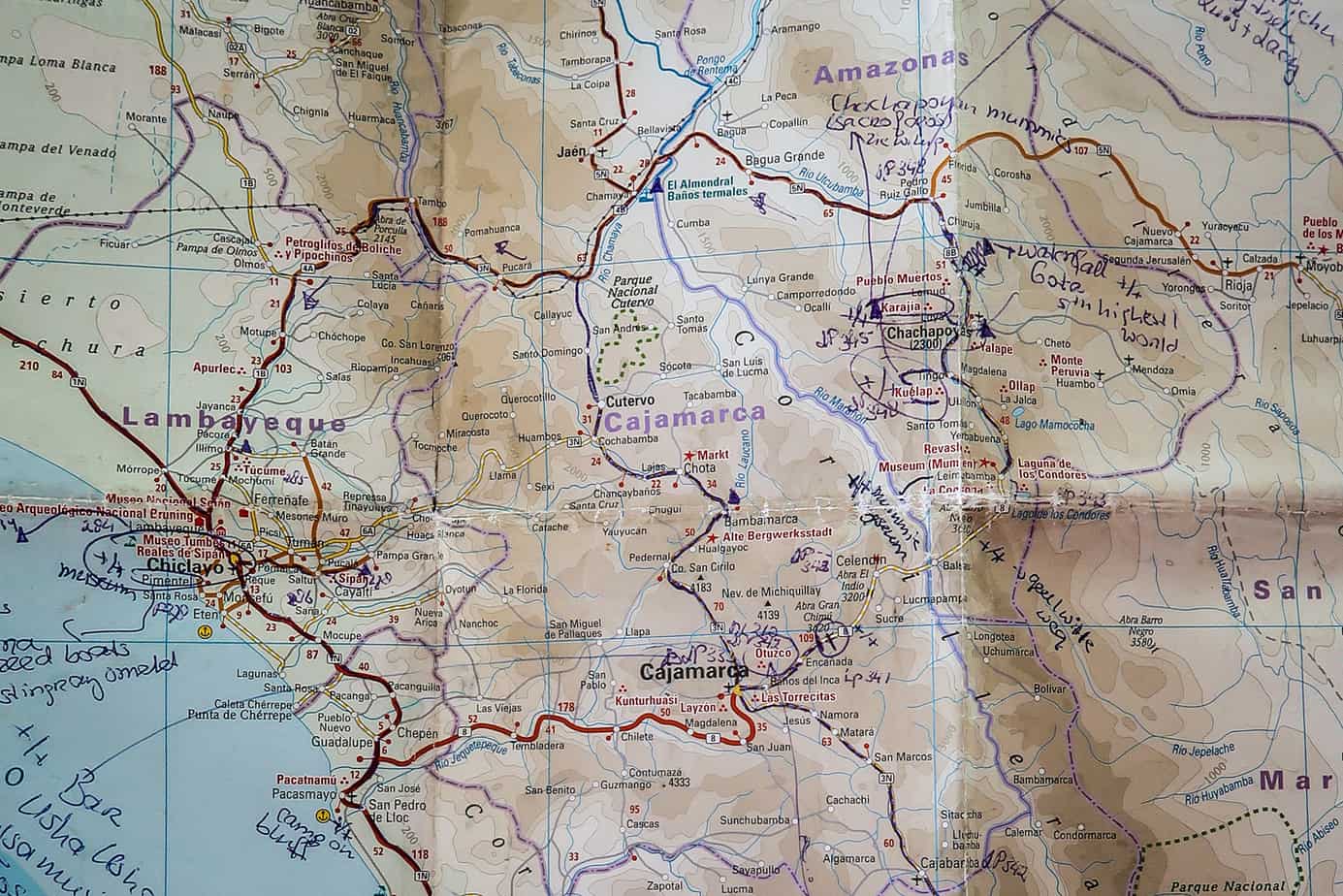

The city of Cajamarca was worth the effort. It is a laid-back town in a region that was inhabited by many pre-Inca cultures long before the Spanish conquered it. The old center is characterized by baroque architecture, including Jesuit churches with ornate façades. Not only did we find excellent ice cream based on regional fruits and made with milk bought from local farms, but we also learned that the production is about more than just making and selling ice cream.

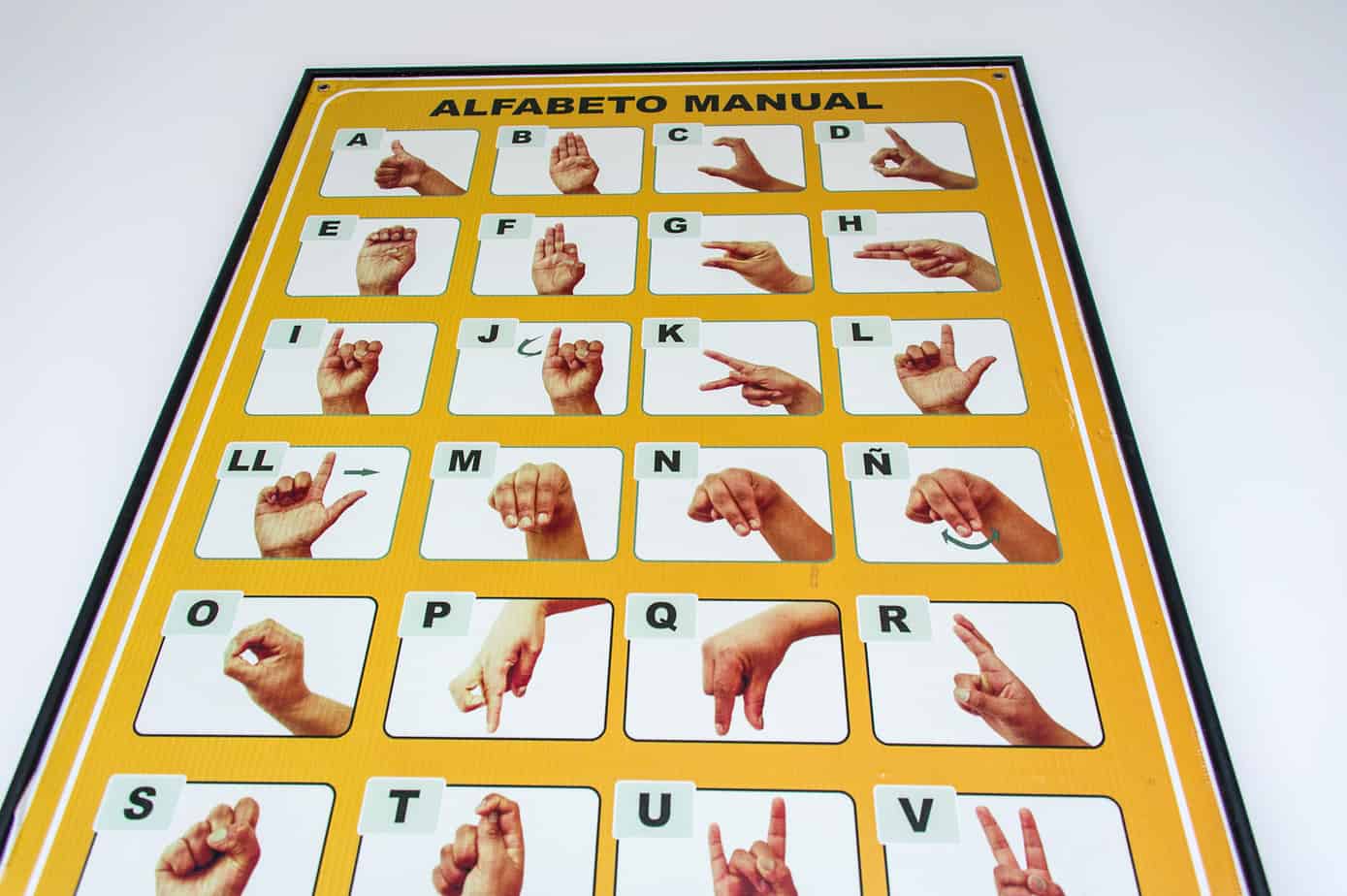

Heladería Holanda is run by the Dutchman Pim and his Peruvian wife, Luz Marina. Their 10 ice cream parlors in the city are all run by single mothers and/or deaf people, and all of their employees are deaf as well. As Pim gave us a tour around the factory, he explained how he and Luz Marina had worked hard to get deaf people out of Peru’s underdog status and had been quite successful. If you want to read more about their project, read here (in Spanish) or here (in Dutch).

It took more effort to “do” this loop than expected, but that was okay. You can’t plan everything on an overland journey, and shouldn’t want to. It is a beautiful part of the country I wouldn’t have wanted to miss. Go check it out!

To learn more about Landcruising Adventure, or read more of their amazing stories, visit their website by clicking the banner below!