I met Andy Audette on Washington’s western coast one summer, maybe four years ago. The sound of a big cylinder diesel is what I remember most. A cream colored Ford with an Alaskan Camper stuffed into the truck bed pulled up and tucked itself into a spot right in front of the ocean. From inside the cab came an attractive young woman carrying a newborn baby, an eight year old boy and Andy. The top of the Alaskan came up and the young woman proceeded to cook a belated breakfast, baby sitting by her side. Andy walked over and introduced himself. Stoked is how I’d describe him.

The next time I saw Andy was at a New Year’s party – a pretty normal encounter all things considered. Drunken chat about dual-sport motorcycling lead me to believe this guy was game for some off-road exploring. Little did I know that he was not only a more accomplished motorcyclists than myself, but also some kind of Indiana Jones reincarnate, having explored every corner of the Pacific Northwest aboard his Honda XR650L motorcycle.

Fast forward a few months and I am sitting beachside yet again, waiting for surf, when Andy rolls in atop his Honda. A quick wheelie across the campground was followed by tent pitching, tiny camp chair sitting and wine swilling from the plastic apparatus Andy had packed amongst his things. This time, fireside chat fueled by booze lead us to another topic: Austin Vince. Now, if you don’t know about this guy, you should dig a little deeper. Some might say he is the father of Adventure Motorcycling, the now overly popular excuse to pack all your shit onto a bike that’s too big and ride off into the sunset… Or just down the street to Starbucks. Austin, however, had done it first. And as far as Andy and I were concerned, he’d done it the right way (read: cheaply). As it turns out, Austin was headed to Portland, OR to debut his latest film, Mondo Sahara, which documented his semi-unassisted crossing of the Saharan desert by motor bike. It also turns out that I know Austin, and was able to sneak Andy, his brother and myself into an otherwise over-sold theater a few weeks later to witness Austin at his finest. This gesture set into motion a visit to the Andy’s property, as well as a search for secret military structures on the Olympic Peninsula.

We arrived at Andy’s place on a Thursday. It was mid-day, and Andy was just leaving for work. “Make yourselves at home,” he said. “I’ll be back around two o’clock in the morning.” We stayed up later than anticipated that evening – drinking beer and discussing the things we hoped to see the next day. Unfortunately, we were startled awake early the next morning by the sound of a KLR 650 firing up right next to our tent. Andy, who had come home in the middle of the night, and hearing the sound of a motorcycle, sprang out of bed, threw on some riding gear and came rushing out of the house. He looked both confused and excited to see it wasn’t us making the noise, but his father. Instead of going back to bed, however, Andy brewed a pot of coffee and showed us around the property – an eight acre parcel located about twenty minutes outside of Port Angeles, upon which Andy , his brother and their father have all built cabins.

An hour later we hopped aboard our bikes and headed west. Washington’s Highway 114 runs parallel to the Strait of Juan de Fuca, swinging on and off the coastline as it travels from Port Angeles to Neah Bay. I’ve driven this road countless time while searching for surf, and almost always notice an assortment of two-track spur roads that lead south into the woods. In our van, however, these seem impassable. But on bikes… Well, that’s what we came here for! The first road we turned down went from rough pavement to loose gravel, and lead us through a small neighborhood of houses. No more than five minutes later and we were surrounded by tall pine trees. The gravel road swayed left and right and then headed uphill. Save for Kyra’s small spill courtesy of a rather large rut, our race to the first of many abandoned military bunkers was otherwise accident and event free.

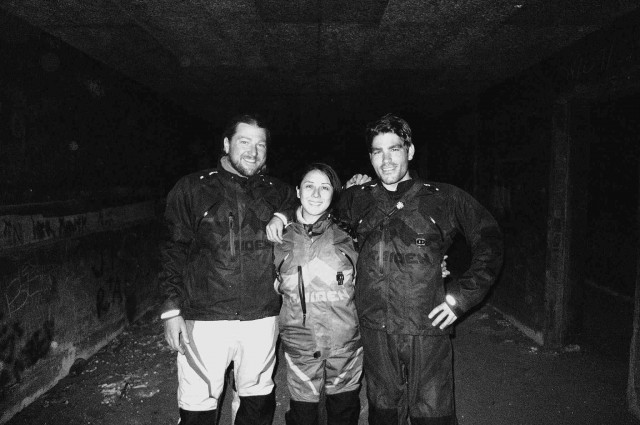

Sitting high atop the Strait of Juan de Fuca, noticeable from only one side, sat the largest of the four bunkers we’d find that day. Parking our bikes on top of it, we climbed down the hillside and came around the back of the bunker to find a huge cement opening littered with graffiti. It was dark inside, but Andy was on it – leading us into the cement shrine with his headlamp. We followed with cell phone flashlights. “This is the biggest one we’ve found so far,” Andy announced. “You could get lost in here.” I snapped a few photos of the different rooms. Cement mounting structures were scattered across the floor. Perhaps once home to… ? We wandered about for a while and then boarded our bikes, leaving a trail of dust behind us as we disappeared down the dirt road.

The next bunker Andy was kind enough to show us was buried deep in the woods. An otherwise overlooked right turn down a dry and rather deep creek bed filled with large rocks, turned to single-track and slithered through the woods. Andy lead the way, while Kyra, our friend Chris, my father and I followed. Single track took us to a long water crossing, which we forged quite quickly. Another tight right turn took us through tall overgrown ferns and into a clearing where a massive bunker sat, looming. Covered completely by moss and vegetation, this would be the biggest bunker we’d see all day. Unfortunately, though, it was sealed shut with some kind of ironclad gates installed in the 1950’s (?). We wandered about, looking for an entrance. Maybe a small opening we could send Kyra through? The only thing we found was an underground generator room that she was able to access via a short ladder. “There’s just a bunch of garbage and some lackluster graffiti,” Kyra noted on her way out. Unlike others we’d see that week, this bunker did not sit directly on the Strait. On the backside, which faced north toward the water, was a huge entrance, presumably where munitions could be unloaded and moved inside. A long since overgrown dirt road wrapped around the bunker, disappearing into the woods. We chatted about the sheer size and security of this particular bunker. “I bet there are multiple levels in this one,” Christopher guessed. “It’s so massive, it was probably used as a distribution point for all the other bunkers out here,” my father added. “I bet there are underground tunnels that lead to all the other bunkers!” Kyra exclaimed. Our speculations lasted another half-hour. By the time we were ready to leave and look for the next piece of overgrown American history, the amount of daylight remaining had dwindled considerably. “Perhaps we’ll save the rest for another day?” Andy asked. “There are so many of these things out here, we could spend an entire month looking for them.” Now that’s what I like to hear! Tip of the iceberg, if you will.

And so with the sun setting at our backs, we headed east toward town, riding the same rock-strewn roads that lead us in. Campfire chat that evening was quiet and thoughtful; each of us filling in the blanks about these bunkers, the men that once occupied them and the amount of time they’d sat unused. It was an adventure, that’s for sure, one that would last a few more days…