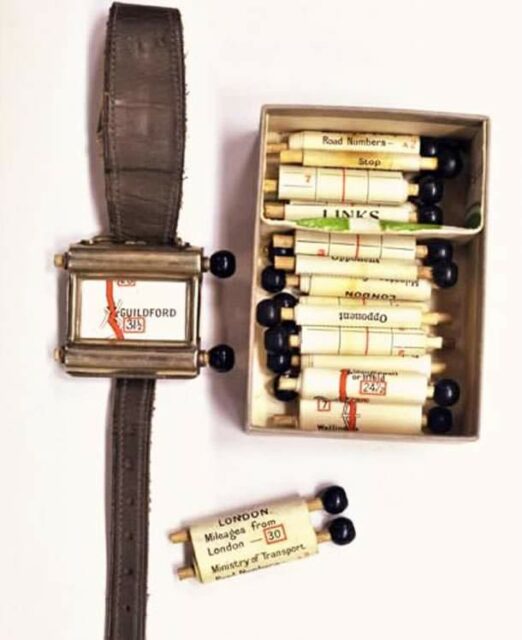

Imagine chugging down the bumpy roads of 1920s London in a Ford Model T, mechanical parts clattering away as you grip the manual steering wheel, shifting between high and low gear. Perhaps you are heading for the coastal town of Bournemouth in Dorset, England, eager to enjoy a weekend by the sea. To navigate, you examine a tiny paper map loaded onto a watch-type device affixed to your wrist. After each turn, the map—which must be wound by two black knobs on the side of the watch—reveals mileage and a “stop” instruction at the journey’s end. Drive. Scroll. Examine a minuscule map. Watch for traffic hazards. Wrangle steering. Navigate London traffic. Was this tiny navigation gadget ultimately more hindrance than help?

Believed to be the first navigation device for motorists, the Plus Fours Routefinder was made in England in the 1920s. The watch came with 20 or so route maps, such as London to Edinburgh or London to Bournemouth, and if motorists wished to turn off the road, they replaced the map with another corresponding to a number at the junction. A separate scroll was required for the return trip, and if your intended road route wasn’t included in the set of provided options, more maps could be ordered to cover the entirety of the country. Another potential bonus (and a clue as to the device’s target demographic) was that the watch allowed wearers to keep golf scores.

The Plus Fours Routefinder is one of 1,400 inventions and contraptions owned by Maurice Collins, a retired businessman from London. “[I] found the Route Finder whilst at an antique fair in the south of the UK,” he says. “I never found out much history. It seems to have had a short commercial life, as I’ve never come across another.” The watch joined a host of other peculiar items on display at the British Library’s Weird and Wonderful Inventions and Gadgets exhibition in 2008. “It’s very amateurish and very simplistic,” Collins spoke of the Routefinder to the Daily Mail. “Sadly, I’ve never tried it myself, and I’m not sure how successful it would be as a navigation device. It’s a bit of an eccentric invention.”

Eccentric, indeed. As a millennial who used paper road maps and MapQuest printouts before TomTom and Garmin brought us personal navigation devices, it’s easy to dismiss this archaic and seemingly impractical device that never really took off. Why this itty-bitty navigation tool was never mass-produced is open to debate. Some point to the limited customer base as vehicles were expensive luxuries limited to few potential watch-wearers. This makes sense. In 1931, there were 2.3 million motor vehicles in Great Britain, which then had a population of 46,073,600. Whereas in 2022, approximately 60 percent of those living in Great Britain owned a licensed vehicle. I would also suggest the impracticality of scrolling while driving posed a hazard (sound familiar?).

While there are hundreds of potential reasons why the Routefinder wasn’t a hit, the idea of a scrolling navigation device popped up again in the early 1930s with the creation of the Iter Avto navigation unit. Developed by the Italian Touring Club, the Iter Avto was a bulky box mounted to your vehicle dashboard and attached to the speedometer, syncing long paper scrolls with distance traveled. The maps featured surprisingly detailed routes, showing bridges, garages, hotels, and other noteworthy items suited to the wayward traveler’s desires. Like the Routefinder, the Iter Avto never achieved mass success. It is unclear whether the Avto was influenced by the 1920s watch or a product of great minds thinking alike.

Though strangely tiny, the Plus Fours Routefinder watch lives on within many elements of navigation that we use today. If you pare back current turn-by-turn satellite navigation, leaving aside the coffee shops, restaurants, attractions, and fuel stations, you are left with a few basic symbols such as road lines, arrows, and highway numbers.

Consider the rally roadbook used by moto and quad racers, for example. Often housed in a box-shaped case secured between a bike’s handlebars, navigation directions are printed on a long paper scroll moved manually or electronically by two circular knobs during racing. This setup is strikingly similar to the early navigation devices of the 1920s and 1930s with, of course, a few upgrades such as waterproof casings, USB-powered LED backlights, and the ability to scroll backward if you miss a turn.

There is a present-day gadget that shares some of the Routefinder’s more ludicrous features: the Apple Watch. Loaded with the Google Maps app, users require laser-sharp vision to read pocket-sized directions strapped to their wrists while driving. At least the Apple Watch includes haptic feedback vibrations to warn of upcoming and erroneous turns and offers access to other useful features such as health monitoring, sleep tracking, and most apps. And, of course, the ever-important ability to track golf scores. Perhaps the Routefinder was ahead of its time, after all.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in Overland Journal’s Fall 2023 Issue.

Our No Compromise Clause: We do not accept advertorial content or allow advertising to influence our coverage, and our contributors are guaranteed editorial independence. Overland International may earn a small commission from affiliate links included in this article. We appreciate your support.