Story by Ashley Giordano, Photos Courtesy of the Swiss Literary Archives

Editor’s note: March is Women’s History Month and the Expedition Portal staff would like to acknowledge and celebrate the incredibly brave and courageous women who have come before us and those who will lead the next generation. Whether you adventure far and wide, or close to home, you all make our world a better place.

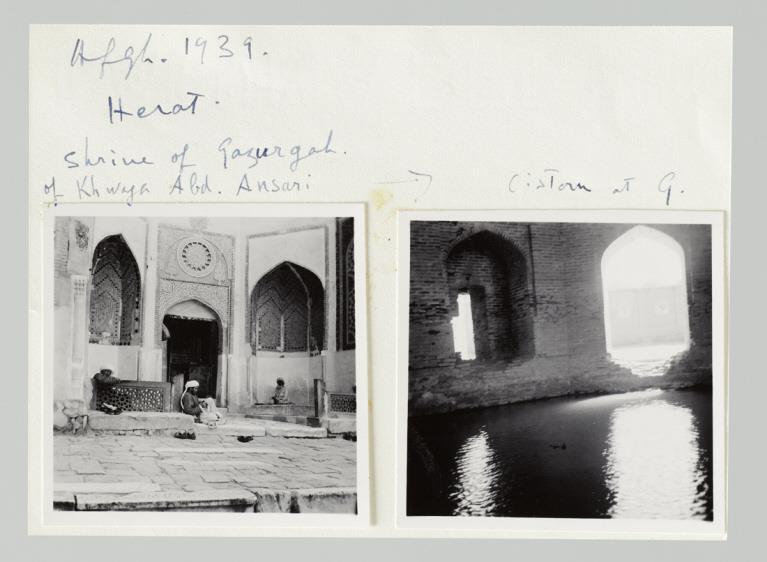

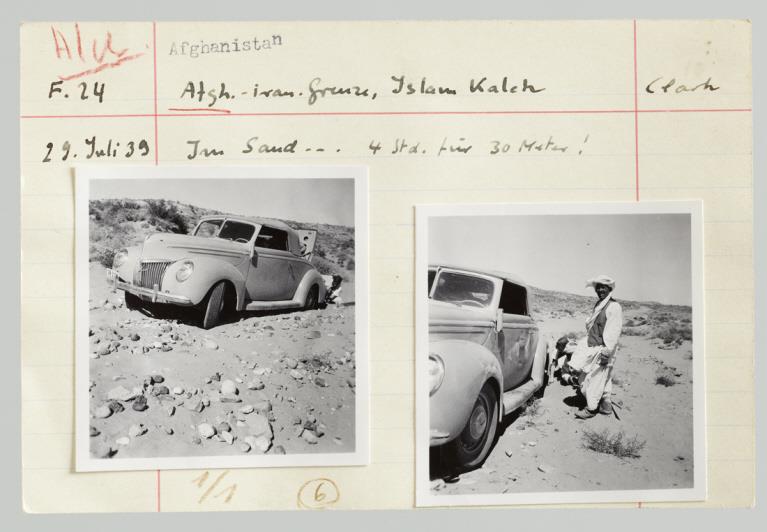

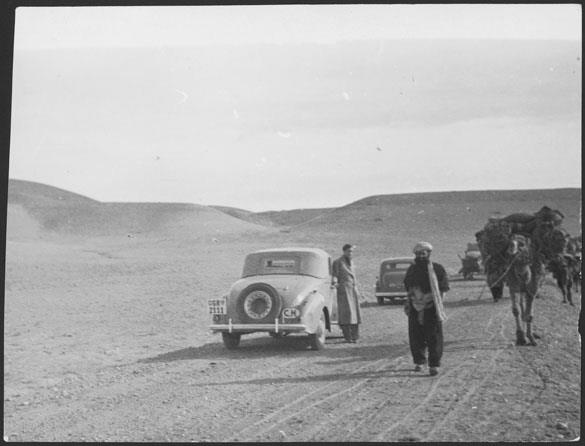

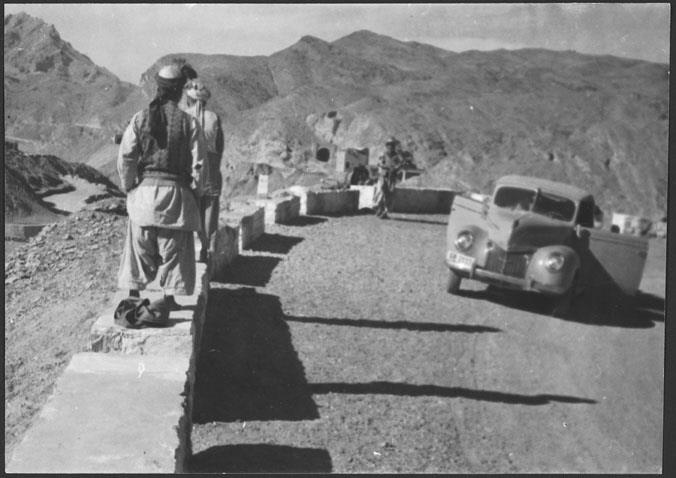

After three months and thousands of miles on pothole-ridden roads, Ella Maillart and Annemarie Schwarzenbach arrived to disappointing news in Herat, Afghanistan. The last snowfall in the region was a heavy one, and the spring snowmelt had destroyed the gateway to Afghanistan’s North Road—the Murghau Bridge. Eyeing their 1939 Ford Deluxe Roadster, a young Polish engineer warned the women against continuing on. “[He] had given us quite an alarming picture of it,” Schwarzenbach wrote in All the Roads Are Open. “Never could a Ford, however powerful, surmount 30-percent grades on mule tracks, cross rivers and defy sand dunes.”

Not ones to be dissuaded, the pair “risked it nonetheless.”

In 1939 Swiss travel writer and journalist Ella K. Maillart set off on an overland journey from Geneva to Kabul with fellow writer and photojournalist Annemarie Schwarzenbach. As the first European women to travel alone on Afghanistan’s Northern Road, the pair experienced a rare glimpse into life in Iran and Afghanistan at a time when their borders were rarely crossed by Westerners. Each wrote their own travelogue about this adventure: Maillart authored The Cruel Way while Schwarzenbach penned All the Roads Are Open.

The Polish engineer in Herat wasn’t the first to cast doubt upon the pair’s plans. In Istanbul, a “bright young engineer” warned the women of Aryan spies in Eastern Turkey, possible arrests, confiscation of their cameras and documents, and experiences that would “forever disgust” the pair with traveling. “You will surely be sent back. Anyhow, whatever you do, don’t ask questions,” he advised.

At the time of their departure, both Maillart and Schwarzenbach were well-versed travelers. From her lodging with Countess Tolstoy in Moscow, Maillart traveled to the Caucasus with a group of students, discovering the hidden valley of Svanetia. Her subsequent explorations through Russian Turkestan and the T’ien Shan range inspired her second book, Turkestan Solo. Reporting for Le Petit Parisien, Maillart investigated Japanese-occupied Manchuria and traveled the Silk Road by “lorry-hopping” into 1939.

Although Swiss heiress Schwarzenbach was Maillart’s junior, she too boasted an impressive travel writing and photojournalism career. Trips abroad included Italy, France, Scandinavia, and Spain. And after that, Persia, Russia and the Balkans, as well as the USA, where she traveled by car with American photographer Barbara Hamilton-Wright, reporting for Swiss magazines about Pennsylvania mining towns and the Deep South in 1937.

By mid-June 1939, Maillart and Schwarzenbach were trundling along to Afghanistan. As to the complexity of the journey, Maillart wrote, “Even for unaccompanied women there is no danger nowadays in travelling through Afghanistan, and my story will disappoint anyone who is looking for adventure.” Although the country itself was relatively safe for travelers at the time, it wasn’t the destination that added a heaviness to their trip. Poor road conditions, harsh landscapes, and the outbreak of the Second World War contributed to the journey’s difficulty, while Schwarzenbach’s struggle with morphine addiction tested the pair’s relationship.

It was amidst the backdrop of Weimar Berlin’s champagne-soaked nightlife that Schwarzenbach first experimented with morphine. Germany’s post-WWI cultural revolution not only made Berlin the decadent party-hub of the country but the intellectual and creative center of Europe. A vibrant cabaret scene promoted creative freedom of thought, embracing sexual liberation and rejecting gender rules. In Berlin, Schwarzenbach openly identified as a lesbian, while her androgynous beauty and anti-Fascist political views enchanted her peers. Ultimately, the Northern Afghanistan trip was an attempt to battle Schwarzenbach’s addiction to morphine and bouts of depression which led to several failed suicide attempts and hospitalizations. “I must go away,” she wrote. “I am finished if I stay in this country where I no longer find any help, where I made too many mistakes and where the past weighs on me too heavily…”

Maillart and Schwarzenbach rendezvoused in the Upper Engadine Lake District of Switzerland, where a fragile Schwarzenbach was convalescing. Cigarette in hand, she mentioned something to Maillart about her father’s promise to provide her with a new Ford. Maillart exclaimed, “A Ford! That’s the car to climb the new Hazarejat road in Afghanistan!” She recounted her recent experiences in India and Turkey. “I am not likely to forget that dusty journey with its many breakdowns, the fervour of the pilgrims, the sleeping on the road or in overcrowded caravanserais, the police inspections at each village and—more difficult to laugh away—the necessity of staying by the lorry instead of roaming at will.”

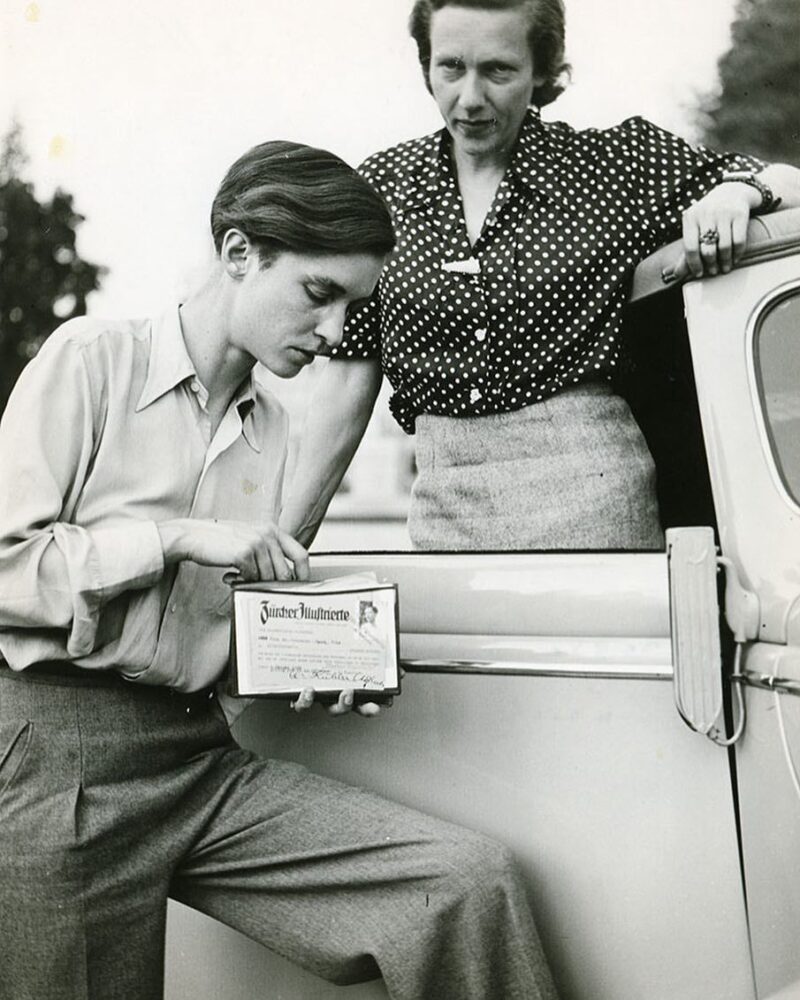

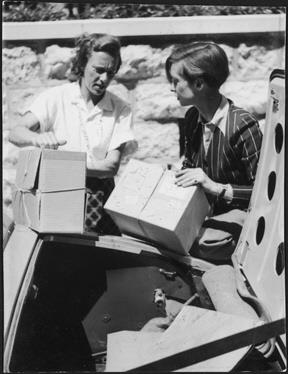

Although World War II wouldn’t officially begin for another few months, the threat was very real. “This journey is not going to be a sky-larking escapade as if we were twenty,” Schwarzenbach noted. “That is impossible with fear of Hitler increasing day by day around us.” The women moved forward with their plans, choosing an 18-horsepower Ford Deluxe Roadster, modified in a Zurich garage. Loaded with a second spare wheel, luggage rack, and a second fuel tank at the back, the vehicle was also weighed down with a couple of typewriters, video cameras, a Rolleiflex film camera, and copious amounts of film.

To help finance the trip, Maillart and Schwarzenbach signed a contract with a Zurich press and photograph agency, while Schwarzenbach secured advances from a publishing house and two newspapers. The pair traveled to Paris, London, and Berlin, where they visited “museums, consulates, publishers [and] geographic societies” to gather information on the countries they planned to visit.

Soon the 30-something intrepids were on their way, rolling out sleeping bags and erecting a tent near the mountain streams of Italy, sipping ice cream at the piazza in Trieste, and settling into life on the road. It was important to them to remain flexible and travel slowly, as Maillart puts it, “noticing all those little changes that make one country different from another…[the] sound of voices, smell of new spices wafting from a farm, coolness of a shy breeze near a brook!”

If the roadster failed, they agreed to continue by local transport. “Our attention was due to all that could be seen and not to what we sat in,” Maillart wrote. The vehicle was a mere vessel, a tool to access what was at the heart of their trip—experiencing Afghanistan, which was relatively untouched by Western civilization at the time—and helping Schwarzenbach. “Away from shaky and feverish Europe I simply wanted to look within,” Maillart wrote. “I…want to sum up Europe from a new vantage point in order to understand the deepest cause of our craziness. Distance would help, I felt sure. In the West, anyway, everyone seemed as lost as I was: why not try the East?”

They motored through Yugoslavia where, to their surprise, people often greeted them with the Nazi salute. Maillart wrote, “Were we taken for Germans? Were we to be flattered…? Could it mean that only Germans were using the roads nowadays?” The grip of Nazi Germany was felt as far east as Tehran, where the gate-keeper, gardener, and seamstress of the German Legation guesthouse performed the salute whenever Maillart and Schwarzenbach passed by.

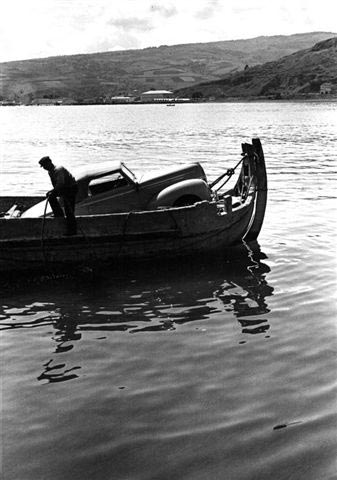

Continuing through the Balkans (“…a whole chapter could be written on them, easily, gladly, now that our Ford, all struggles [have been] put behind it…” Schwarzenbach wrote), the women sailed the Black Sea, eventually arriving in Trabzon, Turkey, where the car was unloaded by “lay[ing] cushions of straw beneath the wheels,” lifting it up with a crane and into a “boat rowed by two men, where the front wheels land[ed] on a bench.” The two women, likely feeling relieved, reunited with the Ford, which, according to Schwarzenbach, was “more or less unscathed in the blazing sun on the quay.”

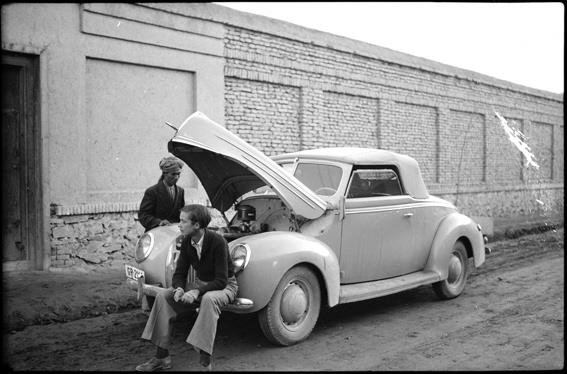

After the turquoise mosaics, vast deserts, stifling dust, and scorching heat of Iran, Schwarzenbach and Maillart finally reached the Afghanistan border. Yelling in victory and congratulating each other, they giggled “like fools.” They had successfully escaped an arrest in Turkey for possession of a camera, moved on from a concerning relapse by Schwarzenbach in Sophia, and overhauled the Ford (“like an over-ripe melon, the chassis began to open as soon as we reached the bad roads,” Maillart wrote) in Bulgaria. Arriving in Afghanistan, the pair was eager to continue along the 500-mile-long road connecting Herat and Mazar-i-Sharif. They then received the news about the Murghau bridge from the Polish engineer.

“I wonder why car-makers think that a Ford will always remain on tarred roads and that loose floor-boards are good enough therefore, for a ‘De Luxe’ coupé,” Maillart questioned. Their V8 had inadequate clearance for the relenting bumps on the road, and Schwarzenbach had to maintain a speed of 45 mph to avoid rattling the car (and its passengers) to pieces. “Ruts and pot-holes are so many in Afghanistan that some people even make out that they are part of its strategic defences,” Maillart joked.

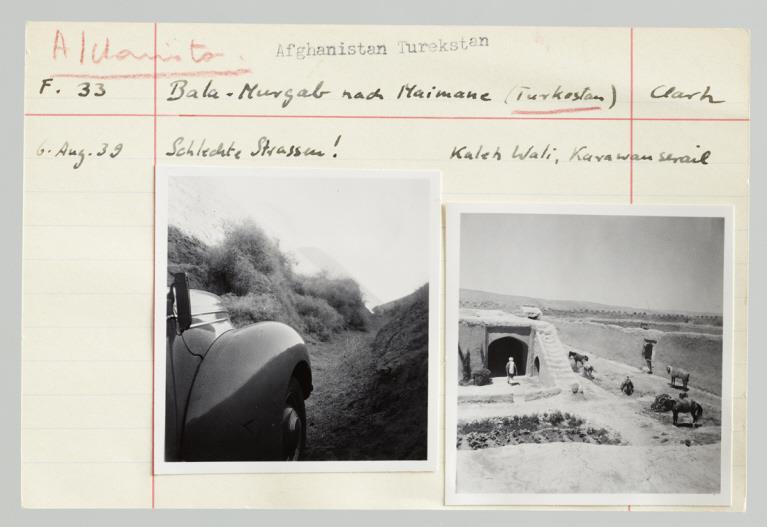

After receiving word that the bridge had been repaired, the two women left Herat on August 2, 1939. They brought an Indian Survey map of 1 inch to 30 miles and were provided with escorts during difficult sections of the Afghanistan North Road. “The mayor advised us to travel to Shibargan in the company of a passenger lorry so as to help if sands were bad. By then, because of the difficult road, we were reconciled to having an escort,” Maillart wrote. In some sections where nothing but ankle-deep dust existed, 12 or 15 road workers followed not just the Ford but other vehicles as well, “pushing the helpless cars or spreading rush mats before the wheels.”

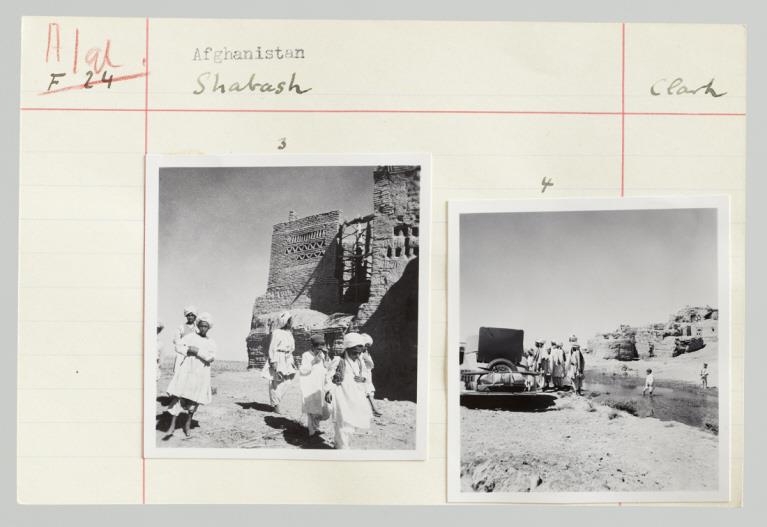

Despite their struggles, Maillart and Schwarzenbach reveled in their surroundings. Although they followed in the footsteps of Hsuan Tsang, Ghenghis Khan, and Marco Polo, life was just as different then as it would be today. Local women were few and far between, but when spotted, they were unforgettable in “dark-red garments under black head cloths.” Round felt yurts mingled with black tents; men took breaks from harvesting wheat with sickles to wave at the two unusual travelers passing by; tall camels lined the roadway, while tea and rest houses made convenient places to stay. The pair ran into a group of gypsies (“riders, walkers, bears, monkeys, children” on their way to Kandahar), two women from the Maldar Kutchi tribe, and thousands of men (“gentle Hazara, Tadjik, Afghans, Uzbeks, Turkomens”) who were constructing the Pol-i-Khumri dam in the Kunduz Valley.

Maillart and Schwarzenbach arrived in Kabul just shy of the outbreak of World War II in Europe. “Uncertainty took hold of our lives,” Maillart wrote. Schwarzenbach confessed that the war and resulting upheaval of their plans had shaken her. She had succumbed to her craving for codeine. Their friendship took a hit as Maillart felt she failed Schwarzenbach. “Deep in my heart was an unshakable confidence in [Annemarie] and that my double aim—Kabul and helping her—would be attained,” she wrote at the outset of their trip. Although the two parted ways, they remained friends until Schwarzenbach’s untimely death in 1942 due to a bicycle accident.

Although Ella Maillart and Annemarie Schwarzenbach might not be here to share their stories today, their words and photographs live on. Their desire to be, as Maillart put it, “…unencumbered by possessions, everywhere at home, intensely alive, without masters, unlimited by nationality” makes these two legends not just in their time, but in ours as well.

Read more: What I Learned From These Women of Overlanding History