Adventure often parallels life, the storms and floods coming at unexpected intervals, with summits only attained after careful planning and much work. Utah has always been a reminder of reality, an escape from my bourgeois career in advertising. It has become a habit to drive my trusted Land Rover Discovery to the Colorado Plateau during any break in my schedule. Utah is a place of story, possessing a visual narcotic few other landscapes can match. Often alone, I purposefully eschew modern navigation tools like a GPS, resorting to maps of any character and age to reveal the secrets of both the cartographer and Mother Nature. These roads have led me to unimaginable wonders, from ancient, intact pottery fashioned by the Pueblo people to deep slot canyons that have tested every fiber of my body. Some of the campsites and vistas so moved me that I have never spoken of them again. Not for selfish reasons, but out of a responsibility to help preserve the raw nature of this landscape.

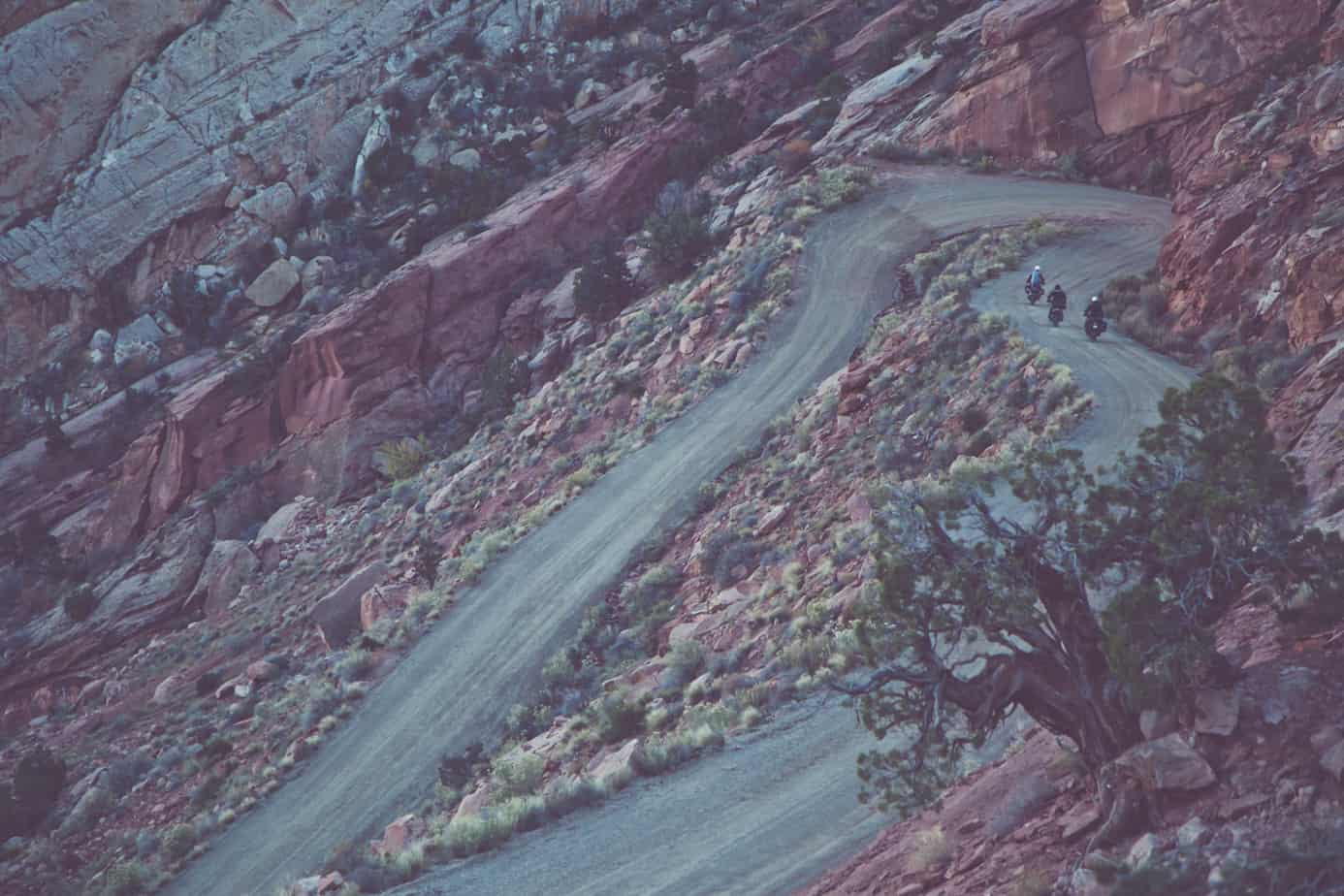

Like a production deadline, the clouds had piled against the Orange Cliffs, unleashing their torrent on sandstone, soil, and the only souls on the Flint Trail—two travelers in one 15-year-old truck. The Flint Trail shelf is quite modest when things are dry and dusty, and I had traveled its switchbacks countless times. However, this journey was different. A historic 3.5 inches of rain fell in just a few hours, cutting large gaps in the track, isolating us from the ranger station on the mesa, imparting a sinister feeling to the gravity of the situation and trail conditions. There was no turning back, as we were above the bentonite layer that had become the consistency of Greek yogurt, sliding the Discovery from one side of the trail to the next. We pushed on, one switchback at a time, walking sections first to make sure the road had not been washed out. With each turn, my confidence climbed. The clouds ebbed and flowed, only giving a glimpse of the immense landscape below. Reaching the crest of the cliff we paused, relishing the relief of having made it, closing our eyes for a moment to take in the sound of the now-soothing downpour. This is the Utah Traverse.

–Sinuhe Xavier

THE BASIN AND RANGE REGION

While Sinuhe had traveled across the Colorado Plateau dozens of times in his Land Rover Discovery, he specifically wanted to complete the Utah Traverse project in its entirety using adventure motorcycles. Late September is the best time of year to cross the state; the perfect confluence of cooler days and snow-free mountains. We certainly wanted to ride the Traverse during this weather window, but as life goes, plans change. We can all appreciate a good adventure, and I have come to love unexpected developments because calamity nearly always ensues. During the first few days of November the team loaded soft luggage onto brand new BMW GSs and motored east—directly toward the first snowstorm of the season.

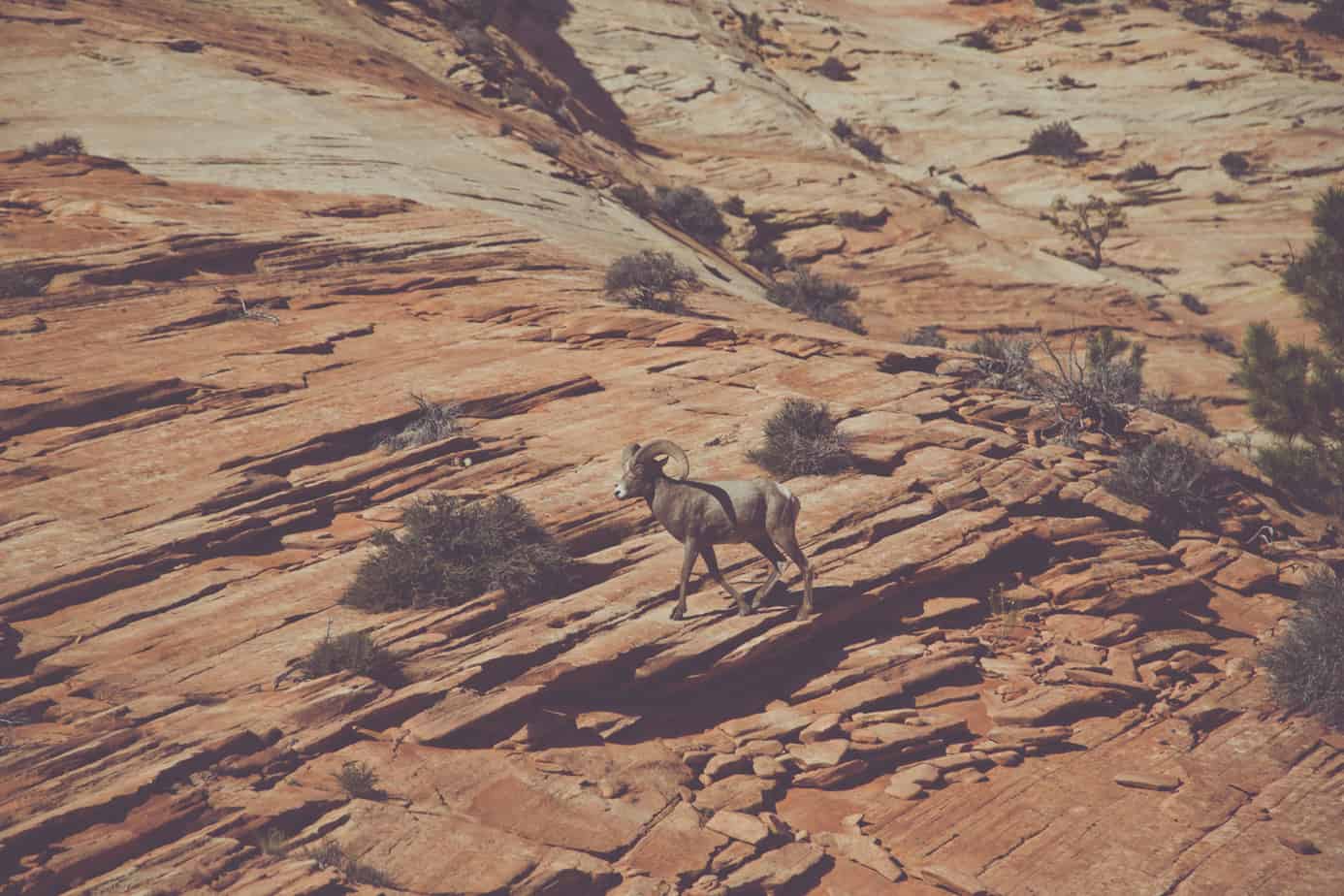

To understand the scope of the Traverse project, it is important to provide perspective on the immensity of the Colorado Plateau, a massive uplift covering 140,000 square miles of Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, and Utah. Comprised primarily of a high-desert crustal block, there are several mountain ranges that extend beyond the mesas and canyons. Various stratigraphical features punctuate the surface, most notably from the Permian through Jurassic periods, which make up the stunning Navajo Sandstone, red Kayenta Formation, and white Cutler Group. These surfaces are so ancient that dinosaur footprints can be found crisscrossing the slabs. This is the appeal of the plateau, the aura that draws adventurous souls.

Our first day brought the convoy through St. George to Rockville, where we met up with the remainder of our group. On a well-used BMW R1150GSA was Stephen Smith, a professional photographer and accomplished vagabond, with a (soon to be discovered) penchant for a fist full of throttle. From the east came Bill Dragoo, a regular contributor to Expedition Portal and a noted motorcycle trainer and adventurer. Bill was riding a fully farkled 1200GS waterboxer with a winch on the pillion rack. Rounding out the group was our film director, Max Daines, and his assistant, Cooke, in a discreetly modified 4WD Tacoma. We loaded up on provisions and hit the dirt, crossing the Virgin River and climbing Smithsonian Butte Road to a campsite on Gooseberry Mesa. Even this far south in Utah the scenery is spectacular; a narrow thread of two-track led us to a breathtaking overlook adjacent to camp.

The next morning started early and included our first breakdown, the 1150 failing to start after crossing the Virgin River bridge. We moved (okay, wiggled) a few wires and it shuddered to life, but we knew a more detailed repair would be required. Bill immediately dug into the charging system and isolated the problem to a faulty ground. We were back on the road carving corners and dragging pegs (or so we wished) along State Route 9, the granite towers and cliffs of Zion National Park revealing themselves with each turn. The Utah Traverse does not intentionally avoid highways, as the goal is to take in the beauty of the state while crossing it. At times, the highways are exactly where you want to be when there is plenty of dirt ahead.

GRAND STAIRCASE-ESCALANTE NATIONAL MONUMENT AND THE COLORADO PLATEAU

The Grand Staircase-Escalante is the largest of the U.S. National Monuments and preserves 1,880,461 acres from commercial development. This designation does not restrict backcountry travel but does provide overland travelers access to hundreds of miles of gravel roads and technical trails. With more area than Delaware, this region includes the Paria River, the Kaiparowits Plateau, and Glen Canyon. The monument is comprised of deep canyons and enormous mesas, many bisected by dry rivers, slots, and creeks. It is also home to the most remote point in the continental United States, the furthest spot from any incorporated town—this is about as far away from civilization as you can get in the USA without a trip to Alaska.

Our team had made good progress to the Colorado Plateau, the track winding through and around countless valleys and over expansive ridgelines. As the sun set against Smoky Mountain, we negotiated a challenging dirt track to a camp overlooking Paria Canyon—one of the most scenic vistas of the trip. From Skutumpah Road we shifted to pavement at the Kaiparowits Plateau and Highway 12; the distance between Escalante and Boulder is one of the most magical stretches of asphalt in the country. On roads like this is where a proper adventure motorcycle really shows its worth, carrying us and our gear through hundreds of miles of sand and mud, only to transform into knee dragging (again, wishful thinking) chicken strip-scrubbing rockets. There is something special about 125 horsepower and a telelever suspension that brings a giant smile with a twist of the throttle.

Rolling into Boulder on fumes, we also needed to fill our stomachs after a long morning of dust and mire. This is not just a fuel stop; it is ripe for the foodie, with little enclaves of culinary bliss in abundance. We stepped into Hell’s Backbone Grill, a Zagat- and Fodor’s-rated oasis with a curated menu made up of locally grown specialties. It might seem un-overlandy of us to stop for such a treat, but I would submit that just because a big part of overlanding is about being remote, doesn’t mean it has to be primitive.

We rode down the Burr Trail, a scenic road that heads east through Long Canyon and along the Circle Cliffs, before descending a series of tight switchbacks down the Waterpocket Fold. Not only is this literally in the middle of nowhere, it is rarely traveled; from Boulder through the Henry Mountains to State Route 95, we didn’t encounter another vehicle. In this stretch, the landscape becomes more dramatic and textured, the folds and valleys are deeper and the ridges higher. With the storm approaching, we skipped a few dirt sections and made haste toward the Bears Ears and Elk Ridge.

CANYONLANDS REGION

The weather system was threatening, and recent storms had already deposited a layer of white on the Bears Ears and Horse Mountain. This closed off our route on Cottonwood Canyon Road and Elk Ridge, cutting off access to Canyonlands from the south, resulting in a significant detour through Monticello. The hope was that using Beef Basin Road would allow for lower elevations and less snow—luck would not be on our side. By the time we climbed the north slope of Boundary Butte, the mud started, followed by patches of snow. We were only at 7,000 feet and needed to climb another thousand before dropping into Ruin Park. The mud got deeper, and the riders started to fade, one bike after another going down in the slick conditions, sometimes stopping for minutes to clear mud from the front tire and fender. The light was also fading, along with our resolve.

At a long section of snow we assessed our situation, but to my surprise, the entire group was game to continue. We set a hard stop time of 8:00 p.m., where we would set up a bivouac (which means “mistake” in French) for the night. The snow was actually a reprieve from the mud, and though we still dropped the motorcycles, a lot, progress improved. Spirits lifted as we reached the turnoff into Beef Basin, and the decision was made to press on for lower elevations and hopefully drier conditions. The trail turned again to quagmire, but gravity was on our side—by midnight we were making camp, completely exhausted.

The following morning brought us to the top of Bobby’s Hole, an infamous descent filled with ledges, loose sand, and huge boulders. Stephen made a valiant effort to ride it, but the event looked more like an avalanche of BMW, Jesse Luggage, and rider than something from the Erzberg Rodeo. Thoroughly chickened out, Sinuhe and I rode the top and bottom sections, choosing to save these borrowed bikes for future challenges. With the help of three people, we each slowly walked the heavy machines through the worst of it. Last was Bill Dragoo, who through a combination of significant skill and complete fearlessness rode the entire thing, never dropping and barely dabbing. From that point forward he was (and forever will be) known as the Mighty Dragoo. Continuing through the Needles District, colorful sandstone spires stood as sentinels guarding the entrance to Devil’s Lane and Elephant Hill.

Progress was slow, and we reached the Silver Stairs late in the day, these first ledges and drop-offs a warm-up for the challenges ahead. We continued to push hard, and I could see judgment failing with a few of the team, some choosing to ride each obstacle faster in the hope of not crashing. Inevitably, this just resulted in more drops and fatigue. I cannot describe adequately how difficult it is to ride big adventure bikes up massive ledges and over giant boulders, but a few rounds in the Octagon with Randy Couture comes to mind. By the time we reached Elephant Hill, the sun was beginning to set, and we were just getting started. We all dropped bikes and struggled under the weight and exhaustion, pushing, pulling, and ultimately winching the motorcycles to the top.

Stephen was approaching extreme fatigue and started to use excessive throttle to solve problems. This ultimately resulted in crashing the 1150 into the side of the cliff, caving in the fuel tank, and destroying the front brake master cylinder. After righting the GS we noticed his front forks were also bent and there was not a straight panel left on his panniers. However, we still had to get three bikes up the last switchback, a huge slickrock chute that climbs at a 45-degree angle. Bill was the first to attempt it and managed to jump the 1200 from the initial ledge, halfway up the face, essentially lofting the front wheel for over 15 feet. He stayed in the throttle and made it all the way to the top—incredible. Next was Stephen, who lost traction at the ledge and dropped. Trying to walk the motorcycle up he burned out the clutch; it would no longer climb. Bill grabbed his Warn winch and pulled the 1150 up two more ledges before it came to a rest at the summit ridge. It was completely dark now, and I still needed to ride my GS up most of the hill. With a combination of bouncing, delicate clutch work, and dumb luck, I made it up the first two switchbacks under my own power. We were all sweating profusely by this point and clamoring for water.

It was well after 7:00 p.m. and the trail was not over. We had let the 1150 clutch cool, and on level ground the motorcycle would now move (barely) under its own power. Stephen still had no front brake, and several significant obstacles remained. We started the boxers and headed downhill. I was so exhausted I hardly remember the rest, huge rocks and ledges barely illuminated by factory headlights. This was some of the most technical riding of the journey. We rolled out onto the asphalt with an audible sigh of relief, shutting off the motors and taking inventory of the damage. After airing up the tires we headed east toward Moab, weary but energized by the adventure of the day. The solitude in my helmet was briefly interrupted by Sinuhe on the SENA communicator: “That was amazing,” was the only thing he said. Yes, it was.