Mauritania has an air of infinite sunburned monotony, the entire country a distant sandy horizon wallowing under a powder-blue sky. Maps of the country only highlight the emptiness, the few landmarks achingly lonely amongst the dunes. Of all the maps.me files I downloaded for the commute, the Mauritanian one measured only 12MB. In contrast, east England, one of eighteen files covering the UK, consumes a meaty 47MB. Even Mali’s map, a similarly desert covered country, is four times bigger than it’s vacuum-like coastal cousin.

An hour or so after leaving Hotel Barbas we had reached the border, leaving Morocco to cross a kilometre of no-man’s-land before Mauritania. I shall dedicate only a few sentences to the border crossings on this trip. I have read far too many accounts of heroic overlanders struggling against the tyranny of African corruption to be able to add anything new to the topic. In summary, all African borders are tedious, time-consuming, sweaty and unpredictable, and the relief is overwhelming on making it through intact.

Manned by a policeman in a filthy puffer jacket and moth-eaten trousers, the first roadblock en route to Nouadhibou certainly reminded us we’d left Morocco, home of pressed, shimmering, shiny uniforms. Set on a wagging tongue of land poking out from the coast, Nouadhibou is the second-largest city in Mauritania and appears to straddle both the old and new Mauritania. Perhaps most symbolic of the old, tired, tumbledown Mauritania is Nouadhibou’s maritime graveyard, the final resting place for ships from all over the world, dumped by their owners, exploiting the country’s lax rules. If you can get away with dumping a ship, I thought, then are there actually any rules here at all?

Our search for the ships took us to Cap Blanc, the end of the Nouadhibou peninsula, where weather-beaten cliffs drop away sharply into the Atlantic. We were shown around alongside a group of German Catholic missionaries by a cheery Mauritanian soldier who even opened up the visitor centre, plugged in the VCR and TV, and played us all a clip of sea lions frolicking off the Mauritanian coast. We found the ships on the way back to the campsite, a line of them sat beached in the surf, crumbling and ugly, each with a rope running to the shore, as though someone was worried about them floating away.

In the morning, we shared a cup of tea with Christian; a bus-related import issue had meant he’d spent a night in Nouadhibou instead of driving straight to Nouakchott to meet his friend. We discussed our Mauritanian route. Mauritania represented our ever-present dilemma, how long to spend in each country and still ensure I got to work on time, even in the event of an expected delay. We decided to stay on the coast road for now, from Nouakchott we could re-consider and potentially head southeast into the desert. I’d have to return and do the west coast over the course of a year, I figured, giving myself ample time to meander around each country on my way to Cape Town.

En route to Nouakchott, there were countless roadblocks, manned by tall, statuesque gendarmes, always polite and always in hotchpotch, grimy, military-esque uniforms. Sometimes they asked sheepishly for cigarettes or a petit cadeau. Unfortunately, we had only brought a small box of English leaf tea as bribe material and that failed to impress them. Let me explain. During a pre-departure trip to Tesco, I had suggested buying some Marlboros as a bribe. However, one of my dad’s friends had told him convincingly that tea would work better. Everyone wants leaf tea in Africa, he claimed. I can confirm that no one, at any point over the five weeks, asked for leaf tea.

Approaching Nouakchott the landscape changed from rolling, empty, desolate desert to the weird and wonderful, the out-of-place and bizarre, an African city at its very best. We passed a Derby Hospital NHS screening service lorry, a line of brand-new Range Rovers and camels riding nonchalantly in the back of HiLuxes, their heads poking up over the cab keeping an eye on proceedings. Chaotic and rushed, with everyone doing their best to ignore all of the laws of the road, Nouakchott had the subtle feeling of a new Africa, as though behind the festering facade something significant was happening.

In the campsite that evening we chatted to a Frenchman in a Land Cruiser Troopy who had shunned the tarmac and driven the 300 miles from Nouadhibou to Nouakchott on the beach, interrupted only by the Mauritanian military stopping him at gunpoint. He was planning on spending another couple of weeks in Mauritania, exploring the desert before returning for another week on the beach. We met other similar people, it seems that given enough time to explore it, people unexpectedly fall for Mauritania, rewriting their schedules to spend as much time there as possible. We also wanted to head into the desert towards Aleg before turning back and following the Senegal River west again to the border crossing at St Louis. However, we figured if the riverside road was slow going we’d be struggling for time. That evening we decided against it and planned to keep heading south on the main road and cross into Senegal a day earlier than expected.

By this stage of the trip, our routine felt entirely natural, travel had become our new normal. Each morning, Dad would wake first and put the kettle on, and upon hearing its familiar squeal, I’d clamber down and join him. We’d exchange sleep-related pleasantries and I’d complain about my dreams. With hours on the road each day, the vast majority of my night was spent driving, crashing, and getting stuck. Breakfast consisted of either scrambled eggs or muesli and yoghurt, the consistency and colour of the latter ranging from near solid to watery and white to e-numbered pink, throughout the five weeks. After a follow-up cup of tea and a review of the map we’d pack up, I’d fold away the tent and fight the cover into place, while Dad sorted our culinary wares and did the morning vehicle checks. Before departing each day, we’d make sure the radiator was topped up with water, and the oil not diminishing too quickly. At a middle-aged twenty-five years, the Land Cruiser dripped a little oil each day and misplaced some water, especially on long, flat, tarmac runs. After paying, peeing, and picking a driver we’d be off.

By this stage of the trip, our routine felt entirely natural, travel had become our new normal. Each morning, Dad would wake first and put the kettle on, and upon hearing its familiar squeal, I’d clamber down and join him. We’d exchange sleep-related pleasantries and I’d complain about my dreams. With hours on the road each day, the vast majority of my night was spent driving, crashing, and getting stuck. Breakfast consisted of either scrambled eggs or muesli and yoghurt, the consistency and colour of the latter ranging from near solid to watery and white to e-numbered pink, throughout the five weeks. After a follow-up cup of tea and a review of the map we’d pack up, I’d fold away the tent and fight the cover into place, while Dad sorted our culinary wares and did the morning vehicle checks. Before departing each day, we’d make sure the radiator was topped up with water, and the oil not diminishing too quickly. At a middle-aged twenty-five years, the Land Cruiser dripped a little oil each day and misplaced some water, especially on long, flat, tarmac runs. After paying, peeing, and picking a driver we’d be off.

The morning traffic out of Nouakchott dawdled along, impatient taxi drivers pulling off the road onto the sand verge to make up distance before getting bogged, their passengers getting out and pushing. Trying to find a quicker way ourselves, we pulled off the treacle-like main thoroughfare and down a side street, the plan working until we turned right at the end and into a crowd that was quickly swallowing the road. Protesters swarmed, waving flags and chanting, banging on cars and thrusting flyers into our hands. I remembered the gov.uk advice I had ignored months ago: “You should avoid all demonstrations,” it warned. Oops.

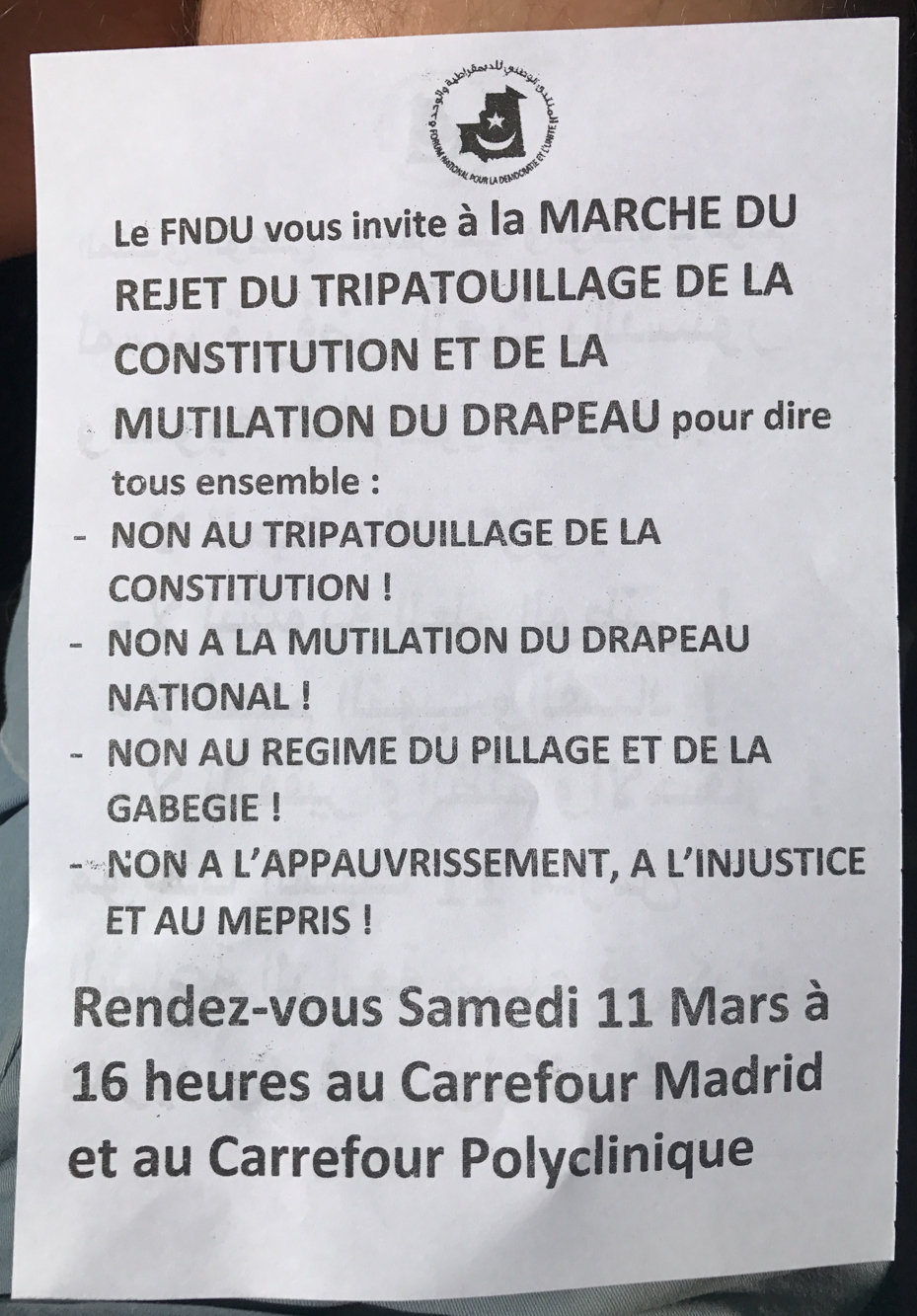

The flyer read (translated from French):

The National Front for Democracy and Unity invites you to walk for the rejection of constitutional tampering and the mutilation of the flag, to say together:

– No to the tampering of the constitution

– No to the mutilation of the national flag

– No to the looting and chaos

– No to impoverishment, injustice, and contempt.

We smiled politely and tried to avoid drawing attention as we crept through the crowd, the roads eventually speeding up as we reached the sprawling outskirts of the city.

After a final morning of Mauritanian monotony, we pulled off the blacktop and passed through the Banc d’Arguin National Park, a wetland reserve home to flamingoes, ospreys and harriers, lots of warthogs and even more corrugations. By mid-afternoon, we had reached the Senegal River, cleared Mauritanian customs, and were into Senegal—country number five.