Photography courtesy of nationalmcmuseum.org

In 1911, a true motorcycling legend, Betsy Leonora Ellis, was born in Kingston, Jamaica; she would later go by Bessie and take on the last name of a spouse. She was tragically orphaned at a young age, then adopted and raised by a well-off Irish woman who would raise her Catholic. The gift of her faith was second to none, but close in impact was surely the motorcycle her mother gave her at the age of 16: a 1928 Indian Scout.

Despite the insistently stated notions of her relatives that suggested her behavior was “unladylike,” and that “nice girls didn’t go around riding motorcycles,” Bessie learned how to ride on her Indian Scout. She eventually used it to speed all along the huge wooden interior walls of an old barrel-shaped motordrome, infamously titled Wall of Death. She had the audacity to perform stunts while doing it, too.

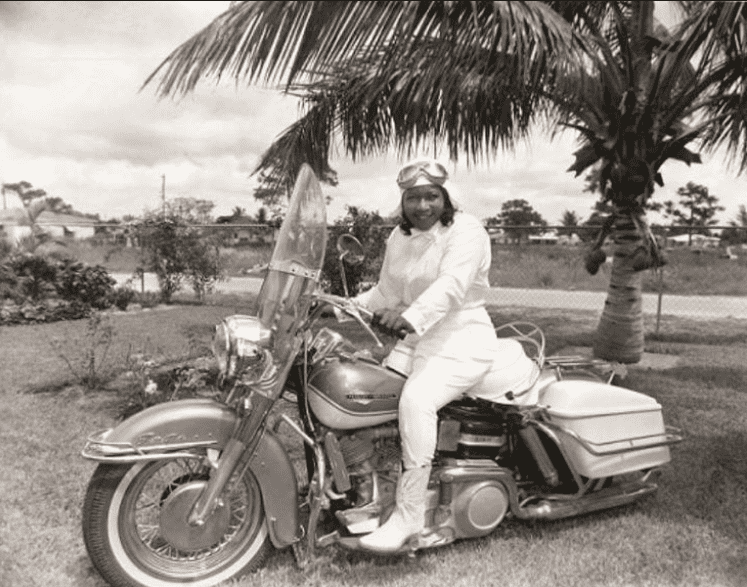

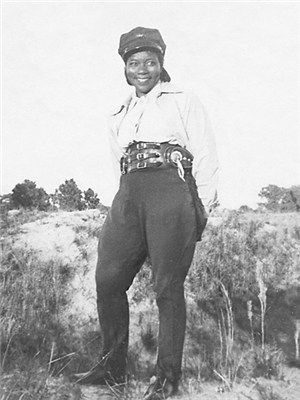

Bessie was primarily self-taught and proved to be quite the natural right away. She developed a love for Harley-Davidsons and owned 27 in her lifetime because, in her own words, “To me, a Harley is the only motorcycle ever made.” With stunning grace and courage, Bessie went on to take eight solo cross-country motorcycle trips. Flipping a coin to decide her destinations, she ended up riding through all 48 contiguous states as a Black woman in the 1930s and 1940s pre-Civil Rights Era. Despite her intersectional identity and the social climate of that time period, she bore no hindrance on her divinely declared path. “My [adoptive] mother said if I wanted anything, I had to ask Our Lord Jesus Christ, and so I did,” she once said. “He taught me, and He’s with me at all times, even now. When I get on the motorcycle, I put the Man Upstairs on the front. I’m very happy on two wheels.”

Her journeys were hardly as easy as hopping on a bike, riding freely, and stopping to rest her head wherever she pleased. She dealt with a great deal of racism. “If you had Black skin, you couldn’t get a place to stay. I knew the Lord would take care of me, and He did. If I found Black folks, I’d stay with them. If not, I’d sleep at filling stations on my motorcycle,” she recalled. On one occasion, she was even pursued relentlessly by a pickup truck driver who intentionally ran her off the road and into a ditch, resulting in her body being completely ejected from her bike.

Bessie often used a social navigation tool called The Negro Motorist Green Book to help her decide where it was best for her to let her boots hit the ground, based on where she was allowed to. These books were pertinent to Black people’s survival while traveling throughout the country during that time period. Inside of each annual issue were lists of establishments such as, but not limited to, hotels, boarding houses, restaurants, taverns, and service stations that were open to serving Black people.

Nevertheless, it would be a great loss not to mention that she was certainly unopposed to breaking her social shackles at times. On one particular occasion in the 1950s, after settling in Miami, Florida, she competed in and won a flat track race, meant only to be entered by men. When she took off her helmet, revealing her identity, the race officials denied her the prize. Bessie continued cycling locally despite misogynistically charged incidents like this and eventually became affectionately known as the “Motorcycle Queen of Miami.”

Beyond her passion for riding simply for thrill and enjoyment, Stringfield also rode as a means of serving her country and making a living on the road. During World War II, she served as a civilian motorcycle dispatch rider. As the only woman and certainly the only Black woman in her unit, she worked carrying relevant documents between domestic bases on her Harley motorcycle. Despite the simplicity of some aspects of her job, she was still required to complete meticulous and exhaustive training maneuvers, such as resourcefully weaving a bridge out of tree limbs and rope to aid in crossing swamps. Outside of her work for the US Army, she made a living for herself during her travels by performing motorcycle stunts at carnivals.

Later on, after her move to Florida, she also had a career in the medical industry working as an LPN (licensed practical nurse) but, no matter what, she kept being called to the road. Around that very same time, she founded the Iron Horse Motorcycle Club.

Even into her late ages, when her health began to wane as she suffered from an enlarged heart, she rode. Although it was against the recommendation of her doctor, Stringfield’s habitual love for motorcycling never wavered. “Years ago, the doctor wanted to stop me from riding,” she said. “I told him if I don’t ride, I won’t live long. And so I never did quit.” To the very end, she was a true “Ride-or-Die.” She later passed in 1993.

Bessie Stringfield was an astonishing woman for countless reasons. She made history and broke early records, but it’s important to acknowledge that it was revolutionary in itself that she even achieved the phenomenal feat of dedicating such a large portion of her life to the pursuit of motorcycling, specifically as a person who was born into a body that was innately controversial in more ways than one.

Even though it wasn’t rightfully acknowledged during her lifetime, much of the due recognition of her success did come posthumously. In 1990, Bessie was featured in the inaugural exhibit of the American Motorcyclist Association’s Motorcycle Heritage Museum, and in 2000, the AMA inducted her into their Motorcycle Hall of Fame. A couple of years later, they named their annual award for Superior Achievement by a Female Motorcyclist in Stringfield’s honor, further ensuring the longevity of her legendary legacy.

Resources

- Nielsen, Euell A. “Bessie Stringfield (1911-1993) .” Black Past, 5 Jan. 2021, blackpast.org/african-american-history/bessie-stringfield-1911-1993/

- Ferrar, Ann. “Bessie Stringfield, Southern Distance Rider.” National Motorcycle Museum, 1996, nationalmcmuseum.org/featured-articles/bessie-stringfield-southern-distance-rider/

- Ferrar, Ann. “Bessie Stringfield, African American Queen of the Road Biography.” Bessie Stringfield | Biography, Memoir, African American, Gender, 24 Mar. 2021, bessiestringfieldbook.com/

- Ferrar, Ann. “Bessie Stringfield.” AMA Motorcycle Museum Hall of Fame | Bessie Stringfield, 1993, motorcyclemuseum.org/halloffame/detail.aspx?RacerID=277

- Gill, Joel Christian. Fast Enough: Bessie Stringfield’s First Ride. The Lion Forge, LLC, 2019

- Green, Victor H. “The Negro Motorist Green Book.” The Negro Motorist Green Book | Smithsonian Digital Volunteers, n.d., transcription.si.edu/project/7955