In our Winter 2018 issue, we ran a story about the new year-round road to Tuktoyaktuk, which replaced what was arguably the most famous ice road in the world. We mentioned how the new road provided a lifeline to the small community of Tuktoyaktuk, in an era of changing climate conditions and uncertain ice conditions. If you haven’t read the article, you could be forgiven for thinking that ice roads are a thing of the past, a throwback to a simpler time. The reality is much different. Ice roads are still a lifeline in many parts of Canada and Alaska. And rather than being behind the technology curve, in many ways they are now at the forefront of road-building technology.

Imagery by Daniel Byrne

People don’t often think of cutting-edge technology when they think of transportation in northern parts. They usually think of dogsleds, kayaks, lumbering bombardiers, and ancient DC-3 bush planes, but around 90 years ago, a new kind of road was pioneered in the Arctic called an ice road. People have been crossing frozen lakes and rivers probably since they first followed an animal across one, but an actual ice road is a different thing. A dedicated route that takes into account the currents below, and has a clear safety margin built in—it allows goods and people to be efficiently transported across the frozen terrain more cost effectively than maintaining year-round roads across the tundra. In the 1930s, as the Canadian Arctic was opening up, engineers worked with local guides to determine where the roads should go, and when the ice would be thick enough to be safe. These guidelines haven’t changed for decades, but now they have to be.

Climate change in the Arctic has changed the ice, and the old guidelines no longer apply. Precipitation has increased in many parts of the north. Shrubification (literally, the land being covered by shrubs) has resulted in more snow being retained on the tundra. That, combined with thawing permafrost, means in some areas the volume of streamflow has doubled in only 20 years. The frequency of rain-over-snow events has also increased. These factors not only change the behavior of currents under the lake ice, but the thawing permafrost combined with increased streamflow is pushing more dissolved organic carbon (DOC) into lakes. More DOC in the lakes, combined with changes in lake currents, results in more under-ice methane being released in the winter months, and methane pockets appearing in places under the ice where it hasn’t been seen in the past. The methane pockets thin the ice above it, usually in patches just large enough for a car or a man to go through the ice, so they are both dangerous and hard to detect.

With all of these climate-related changes, the traditional routes and dates that have been trusted for generations are no longer safe, forcing ice-road builders to use new technology. To see for ourselves, we borrowed a winterized Tiguan 4WD from VW Canada and went to Yellowknife at the beginning of the ice-road construction season to drive on the ice and see some of this technology in action. After a week with professionals from a wide range of disciplines, we were impressed by the way workers across the North are embracing the latest gear to keep people safe and on the move. The bombardiers and bush planes are still there, but a whole arsenal of new technology is being used as well.

Aerial drones – Easy access to aerial drones allows builders to quickly see how much of a lake has frozen, if there are pressure ridges building up in the distance, or if there are any other unusual changes. It also allows builders to scout a new route if the traditional route is found to have thin sections.

Divers under the ice – In the case of vehicles and equipment going through the ice, divers ensure recovery shackles and straps are properly secured. Divers use modern rebreathers so they can breath warm humid air, helping to keep them working for longer periods.

Ice augers and ice thickness gauges –Traditional ice augers and specialized measuring gauges are used with greater frequency to check for thin ice in new areas. Newer gauges slip into the auger hole, and open up on the end like a parachute, catching the bottom the ice, allowing the ice thickness to be read along the shaft. A hard tug collapses the “chute” allowing it to be withdrawn. The older-style gauge, referred to sometimes as hockey sticks, because indeed sometimes broken hockey sticks are used, use the same concept, except that the wooden shaft has a stubby blade protruding at the bottom to catch the lip of the ice. The downside of the hockey stick is the required hole must be larger than a small auger can create.

Argos on tracks – The Argo, the venerable Canadian amphibious vehicle now comes with a track attachment, allowing crews to easily pull the GPR sled across the ice and snow with relative safety.

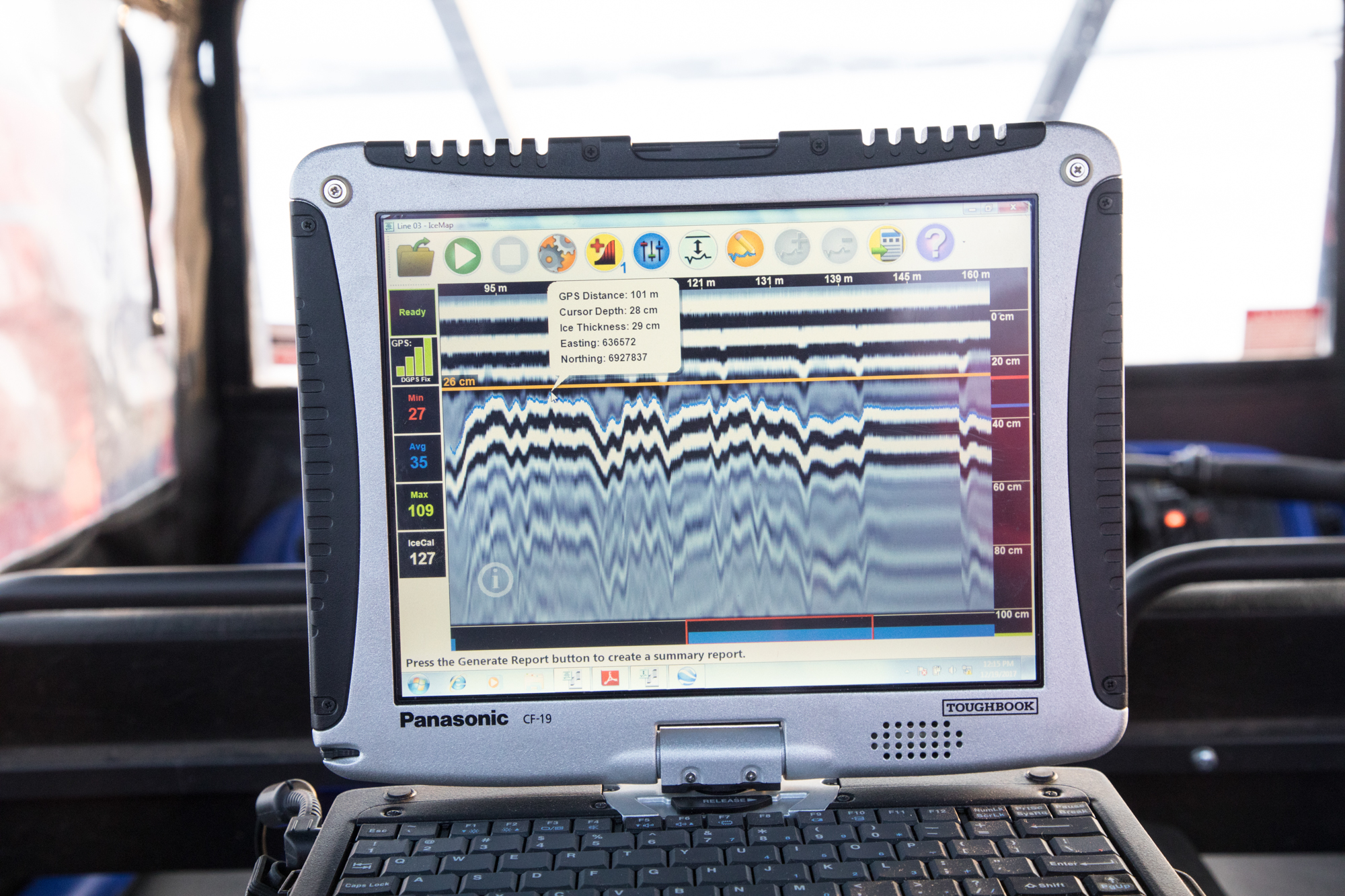

Ground penetrating radar (GPR) – Sled-based GPR sensors with ultra-wide-band antennas allow precision depth measurement of ice as well as the distance to the lakebed. The low-power technology is tethered to the Argo with an umbilical for power and sends data back to an onboard laptop monitored in real time by the operator.

Precipitation monitoring – Snow acts as an effective insulator of the ice below, and will greatly impact the rate at which the lakes will freeze. Precipitation monitoring also gives insight into stream and current impacts. Use of SSMR/SSMI date from Block 5D-2 satellites combined with on-the-ground sampling can provide accurate snow and ice data as well as moisture content information across the territory.

Flood pumps – Big Ice Flood Pumps in Saskatchewan has developed auger, pump, and spray technologies to efficiently thicken ice roads in remote areas. A portable pump with a volume of 120,000 liters per hour means a one or two person crew can actually increase the thickness of a remote road over a moderate area by up to 6 inches per day.

Ice rescue technology – Modern technology helps prevent accidents, but if someone does go through the ice, modern rescue technology like the Mustang Ice Commander ice-rescue suit, combined with ice-climbing mountaineering gear like ice screws and ascenders allow a rescuer to get in the water, retrieve a victim, and come out of the ice unaided.

Medical techniques – A 2016 study conducted in Yellowknife has indicated new treatments for frostbite, including the blood pressure medication Iloprost, which may greatly reduce amputations due to frostbite. Modern communication technology (InReach, Spot, Sat Phones, etcetera) also allows medical professionals to communicate directly with victims in remote areas.

3 Comments

Dman

January 25th, 2019 at 7:56 amFascinating story – but pictures aren’t visible!

Sarah Ramm

January 28th, 2019 at 10:52 amThank you! We had some technical difficulties, but the images are live now. 🙂

Derek

January 31st, 2019 at 11:09 amFascinating story, and great photos!