My journey through the Americas was going swimmingly, if you discount the near-fatal crash of a riding companion in Bolivia, a top-end meltdown (and rebuild) in Peru, and an oil consumption rate that was boosting the South American economy. In Chile, I had met a French girl named Rachel, who was exploring Latin America on her Kawasaki KLR250. We decided to ride together for the last leg of my journey—to Ushuaia, the most southerly town in the world, at the very tip of South America.

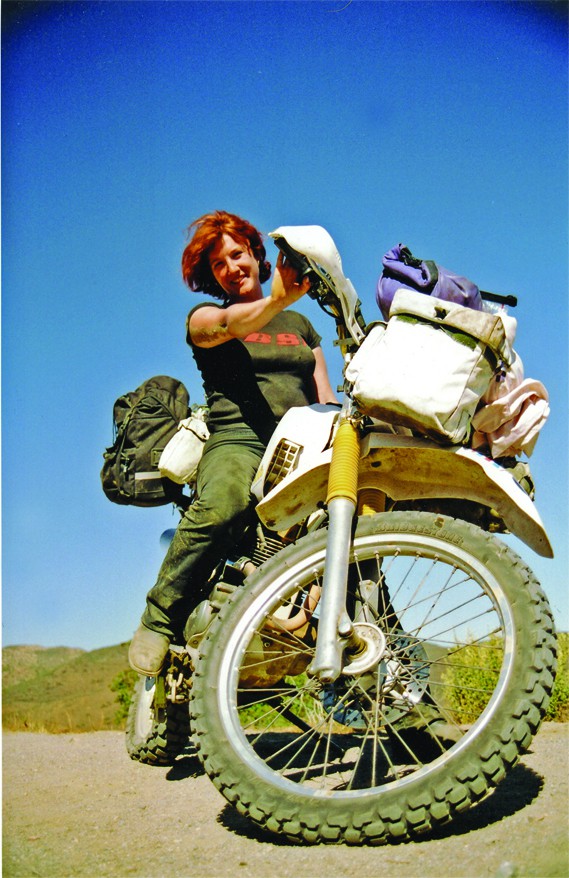

My Yamaha XT225 had clocked 16,000 miles by the time we crossed the border from Chile into Argentina, and after eight months on the road it was beginning to show the strain. Although Ushuaia was now less than a thousand miles away, the terrain and weather conditions of this final stretch across the wilds of Patagonia would be the ultimate test for the little bike—and its rider. The last leg would take me along the infamous Ruta 40 in Argentina, a 600-mile gravel road cutting south across the Patagonian wilderness, renowned for its desolation, its terrible condition, and the battering westerly winds that could blow at a hundred miles per hour.

Everyone we met coming in the opposite direction had a horror story to tell about Ruta 40, each more gruesome than the last, and the motorcyclists who had survived it were only too happy to share their sagas and send fear into the hearts of two hapless southbound girls. Bikes and riders blown clean off the road, engines smashed to pieces, hundreds of miles with no gas stations, legs broken by flying rocks. They looked at our little bikes and shook their heads. “You’ll never make it on those.” And they all had the same look in their eyes, the Ruta 40 look, as if life would never be quite the same again. The touring bicyclists we encountered even had their own name for it: they called it “The Unrideable One.” It didn’t bode well.

As our bald tires crunched on to Ruta 40, a lone armadillo appeared out of nowhere and scuttled across our path. I optimistically imagined this to be some sort of good luck symbol. It never occurred to me that it could be just the opposite. Armadillo—the creature of doom. We emerged from behind the shelter of the last hill we would see for a while and sure enough, a furious side wind slammed into us, sending me flying across the road. We both gasped in shock at the sheer force, and the terrible realization: It was all true.

We fought our way onwards, struggling against the elements, using every ounce of physical strength in our upper bodies just to keep moving forward. It would have been bad enough on a sealed road, but on this potholed, rutted, gravel hell that stretched out in front of us, it was almost impossible to keep moving in a straight line. With the bikes leaning at a 45-degree angle and the engines screaming at full revs in second, we pushed on, every muscle straining; it was the only way to maintain a grip on the road. “Oh my God!” we shouted at each other in utter disbelief. “This is insane!” But we could barely hear our cries over the wail of the wind.

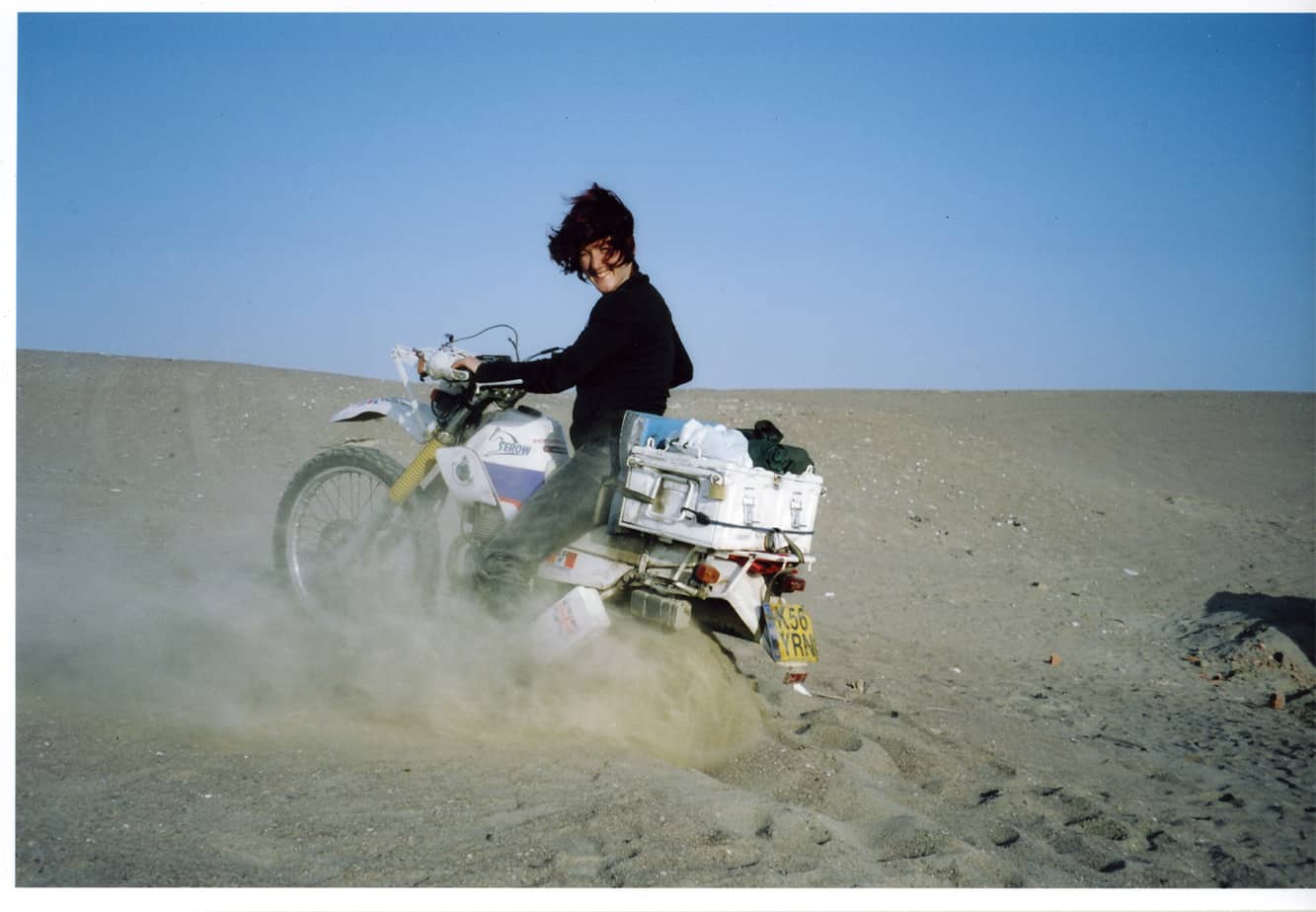

Normally a keen map checker, I couldn’t bring myself to chart our wretched progress. There was no way we would cover this section at our normal pace, but with pockets of civilization spread few and far between, we had to keep pressing on towards the tiny black dots on the map each night—they were our only hope for food, fuel, and water. Despite my long hot haul across Chile’s Atacama Desert, or the desolation of the snowbound Alaskan roads, nothing had prepared me for this. Brown, pancake-flat scrubland surrounded us like an endless sea. There was not a thing on the horizon, not a hill, not a tree, just empty windswept plains and this godforsaken road cutting across it, disappearing into the distance forever. The only changeable features in the scene were the candyfloss clouds that drifted across the giant sky like cartoon thought bubbles.

A black dot on the map marked Bajo Caracoles became our target for the first day, but far from being the village we were expecting, it turned out to be nothing more than a building by the side of the road. However, it covered the basic needs of the Patagonian traveler: beds, petrol, food, booze, and, much to my relief, plenty of 10W/40. Like a Wild West outpost, the bar was full of raucous, weather-beaten men, drinking, smoking, shuffling cards and tumbling dice, and I wondered where they had all come from. We kept a low profile and made for an early night, with plans to get going first thing in the morning, when the winds were supposed to be calmer.

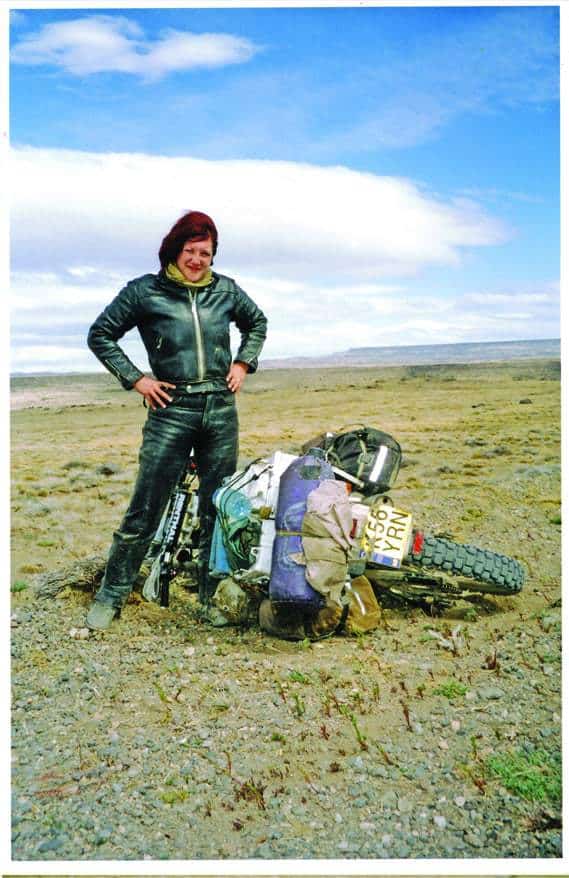

But at 7:00 a.m. a gale was already blowing across the plains, and I dreaded to think how it would be in a few hours. We exchanged looks of apprehension and eased our aching bones into the saddles to do battle with Ruta 40 once again. The wind was worse than the day before— regularly and without warning a violent gust would whip my bike around 90 degrees, sending me careening across the road, sliding and skidding in the gravel, banging through potholes and eventually off the road altogether. I soon devised a method to deal with these incidents by simply steering the bike in the direction the wind forced me, plummeting down the steep bank or flying for yards across the scrubby plain until I could come to a controlled stop.

This survival method worked well enough until such an occasion coincided with Rachel overtaking me on my left. As a furious squall slammed in from the west, spinning my bike around, the front wheel drove slap-bang into her back wheel. I crashed. She looked around to see what had happened. She crashed. It was a comical sight; the two of us sprawled on the road next to our supine motorcycles.

“Are you Okay!?” I yelled, crawling across the gravel toward her. She yelled something back at me, but the sound of the wind rendered our voices inaudible. We dragged ourselves toward each other on all fours, still shouting silently into the wind, and set about picking up the bikes. With them and us upright once again, we attempted to top up our tanks with the contents of my jerry can, but to no avail. The wind sprayed the petrol into our faces, onto our clothes, and all over the bikes. And then once more, straight off the Pacific Ocean, a howling gust slammed Rachel’s bike to the dirt, the filler cap still open, precious fuel disappearing into the dry earth. Gasping for breath, exhausted and aching, we lifted her bike from the ground for the second time and sure enough, another vicious blast screamed across the plains, this time sending Rachel herself flying to the ground.

“WE’VE GOT SIX HUNDRED MILES OF THIS!” we shouted at each other above the roaring in our ears, laughing with adrenalin-fueled hysteria. There was nothing else for it but to continue. Civilization as we knew it was a long way down the road, and the Patagonian landscape remained as empty and bleak as I could imagine. The little black dots on the map became sources of fantasies, but our hopes were regularly dashed when they turned out to be non-existent or, at best, a derelict house. I had never felt so aware of being in the middle of a lonely and hostile land on the edge of the world. “Never again will I refer to the suburbs of London as being in the middle of nowhere,” I solemnly vowed to Rachel that night.

It was difficult to drum up the enthusiasm each morning. We were thoroughly exhausted from the relentless, grueling slog, and our aching, bruised bodies cried out for respite. Then, at the end of a particularly punishing day, a black dot came up trumps. Tres Lagos was a real place. This meant it had a street with more than two houses on it, and its very own signpost on the highway. There was even a shop, although the stock had dwindled to just a few cans of tuna and a pile of sticky cartons of Chocomilk bearing a sell by date that evoked memories of miners’ strikes and Duran Duran riding high in the charts. The man behind the counter wasn’t in the business of delivering good news either.

“The hotel and the restaurant closed a week ago,” he told us. Rachel and I exchanged our now-familiar look of misery. I tried to find something positive in the idea of sitting in a tent drinking rancid chocolate milk with a hundred-mile-an-hour gale blowing outside. I failed. Out in the street, the light was fading fast, and we began making plans to find shelter behind a building for the night. But in the house opposite a curtain was twitching, and just as we were about to stake out our campsite, an elderly woman stuck her head out the door.

“Chicas?” she asked. “Dos chicas?” We confirmed that, yes indeed, despite our unladylike form of transport, our filthy attire, and distinct lack of make-up or handbags at this precise moment, we were indeed two living, breathing, real-life girls. She ventured down her garden path and inspected us a little closer, just to make sure. Once she’d got a convincing whiff of our sugar, spice, and all things not very nice, she ushered us into her house, plumped up the pillows in the spare room, handed us a pile of towels, and told us to get busy in the shower. We couldn’t believe our good fortune, and we bombarded our hostess with gratitude before collapsing into our beds, where we slept like logs.

In the morning, an inspection of my bike revealed various missing nuts and bolts, and an ominous dark patch on the ground where rear brake fluid had leaked from a damaged hose. The day continued in the manner to which we were now only too accustomed, this time with the added fun of no rear brake and a nagging jangling noise. But by late afternoon we were rewarded for our toil by a welcome change in the landscape. In the distance we could see mountains sweeping upward in surreal shades of pink and purple, and in their foothills lay sapphire lakes, calm and protected from the wind. We knew the worst was over.

The following day a 30-minute voyage carried us across the Straits of Magellan to Tierra del Fuego, the island at the tip of South America. I hung over the railing, gazing into the choppy waters, and thought about Sir Francis Drake, who negotiated this passage in a wild storm nearly 500 years ago. It was a humbling notion. What would he have made of this silly adventure of mine? I longed to have been born into a time when great swaths of the Earth were still wild, mysterious, and unexplored, when parchment maps still warned “here be dragons” on the edges of uncharted territory. Maybe there was no true adventure left to be had in this shrinking global village of ours?

No—adventure is a personal thing, I decided—it means whatever you want it to. To me it just means having a go at something that might be exciting or difficult, just to see if I can. And at that moment, with a timing normally reserved for feature films, the sun came out and a school of dolphins leapt out of the water alongside the boat, flipping their tails, arcing and spinning in the air before disappearing back into the sea. I’m on my way to Tierra del Fuego, I thought jubilantly, me and my motorcycle, all the way from Alaska! I don’t know about you, Sir Francis, but I think that’s pretty darn exciting.

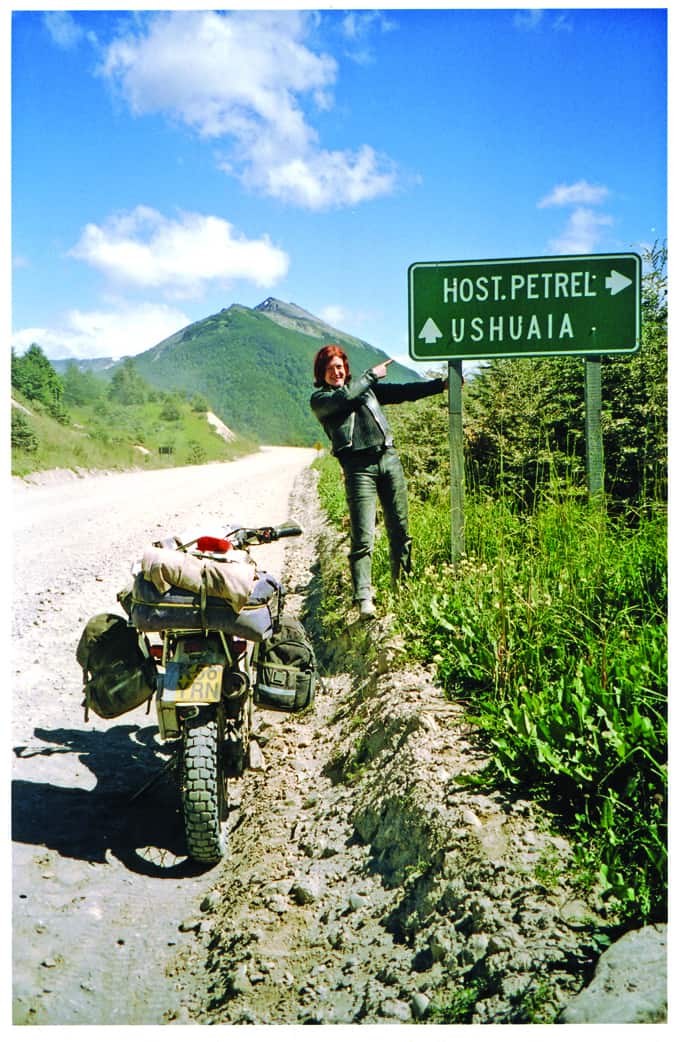

The route to Ushuaia was dirt all the way, and the dustiest road I have ever ridden. Trucks and cars roared past us at impossible speeds, leaving a dense, gritty fog in their wake, so thick that we often had to stop and wait for it to settle. It seemed as though everyone was desperate to get to el fin del mundo. The green signs kept tempting us onwards: USHUAIA and an arrow pointing ever southwards, taking us through a dramatic landscape of snow-capped mountains under a bright blue cloudless sky.

And finally there it was, the sign that I had come all this way for: BIENVENIDOS A LA CIUDAD MAS AUSTRAL DEL MUNDO, and underneath, for those who hadn’t managed to grasp the local lingo yet, WELCOME TO THE SOUTHERNMOST CITY IN THE WORLD. I stopped and savoured the words.

This was it, I had made it. Eight and a half months, sixteen thousand, seven hundred and ninety eight miles. And at this moment, with a timing normally reserved for TV sitcoms, a pack of slavering, barking, feral dogs appeared from nowhere and chased us down the road to the end of the world.