After traveling 8,000 miles over six weeks through Western Germany, Austria, Yugoslavia, Greece, Turkey, Iran, and Pakistan, overland adventuresses Anne Davies, Eve Sims, and Antonia Deacock found themselves in Indian Prime Minister Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru’s drawing room, poring over a large-scale map of the Himalayas laid on a soft white carpet. The “Inner Line,” a buffer state across India and Tibet into which travelers were allowed in only the rarest of cases, was clearly marked in green on the map in front of them. Davies, Sims, and Deacock’s application to cross the Himalayas to the ancient kingdom of Zanskar was refused almost immediately upon its delivery. After an hour and a half with the women, Prime Minister Nehru surprised them all and remarked, “Well, I can see no objection to you young ladies carrying out your plans to visit Zanskar. I will see my foreign secretary about the necessary permits in the morning.”

Six months earlier, Davies, Sims, and Deacock found themselves in another drawing room in Oxted, Surrey. Their respective husbands, all experienced mountaineers, were in the midst of planning the British-Pakistani Forces Himalayan Expedition, the aim of which was to reach the heights of the Rakaposhi mountain in Kashmir. Not ones to sit around at home for four months, the women decided to plan their own adventure.

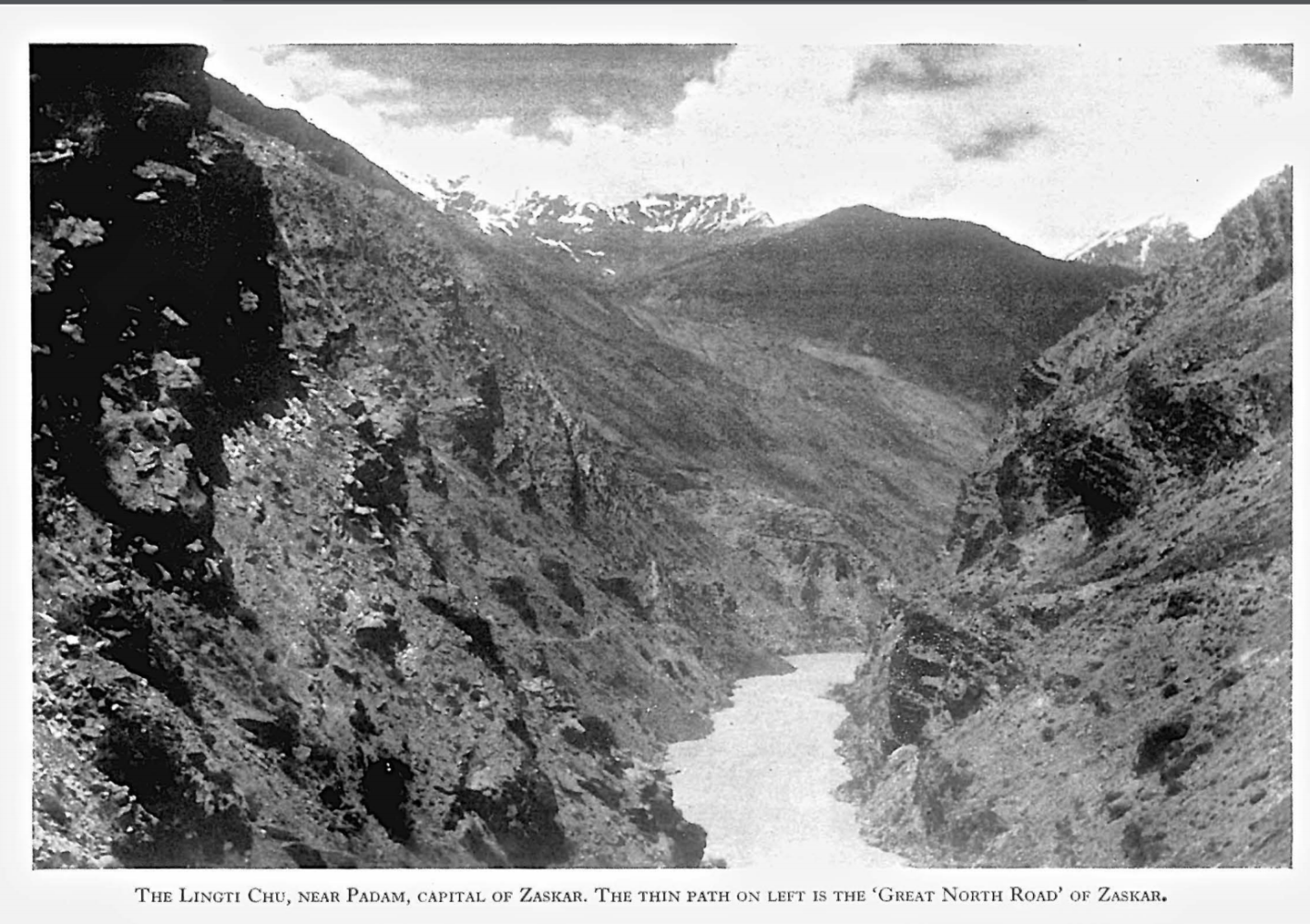

The trio decided to drive to India and visit Zanskar, a small country at the time, but now part of India’s Ladakh territory, lying between India and Tibet. Little was written then about the Zanskari people, and a visit to the Royal Geographic Society library revealed a few sparse details. Intrigued, the women pushed on with their plans.

“The overland journey seemed to offer us the maximum scope for meeting people and seeing at first hand their way of life,” Anne Davies wrote in an article for Alpine Journal. “In our own vehicle, we would be free to stop where and when we liked, and we found that it would be a far cheaper method of travel than the conventional ones, as well as offering a tremendous sense of adventure.”

According to Davies, the women had several goals for the trip, including carrying out a survey regarding the lives of the women and children in Zanskar, learning as much as possible about their social conditions, their way of life, customs, handicrafts, and cooking recipes,’ and to climb an unscaled peak in the region of 17,000 to 18,000 vertical feet.

Despite being referred to by the News Chronicle as “the women who left the kitchen sink to climb to Shangri-La,” Davies, Sims, and Deacock did have previous experience with more than the innermost workings of an oven. Davies lived in India and Pakistan from the age of 11 to 22 and was fluent in both Urdu and Hindi. The Sunday Telegraph indicated she had also “trekked into remote Kashmiri passes with her husband and three-month-old baby, who was strapped to the back of a mule.” Sims learned to climb in Wales and spent two years traveling by motorbike around Australia and New Zealand.

Deacock, also an experienced rock climber, was born in Johannesburg and worked as an architectural assistant in London. Davies was the only one of the group with children—three sons aged 5, 14, and 15. As to how she felt leaving her children for five months, Davies said, “I felt weepy sometimes, but I didn’t feel guilty, because Lester had gone off on expeditions, and this was my turn.”

Land Rover agreed to sell the women a demonstration model of a modified long-wheelbase vehicle for £500, which was a significant discount at that time. Before leaving England, Sims and Deacock passed their driver’s tests, and all three women underwent a five-day maintenance course at the Rover Works at Solihull. They also secured various sponsorships, notably with Ovaltine, who provided the women with a cine camera to film their journey.

After six months of planning, the women left for India. From Eastern Europe to Pakistan, the roads varied, and the Iranian roads were particularly wearing. “We found we could travel at two speeds,” Davies wrote, “either at 10 mph, when we would gently roll from one corrugation to another, or at 35 mph when we would ride the bumps, feel cooler from the breeze, but run the risk of breaking a spring if we hit a dried-up wadi.” The heat became so unbearable in Pakistan and India they only traveled at night.

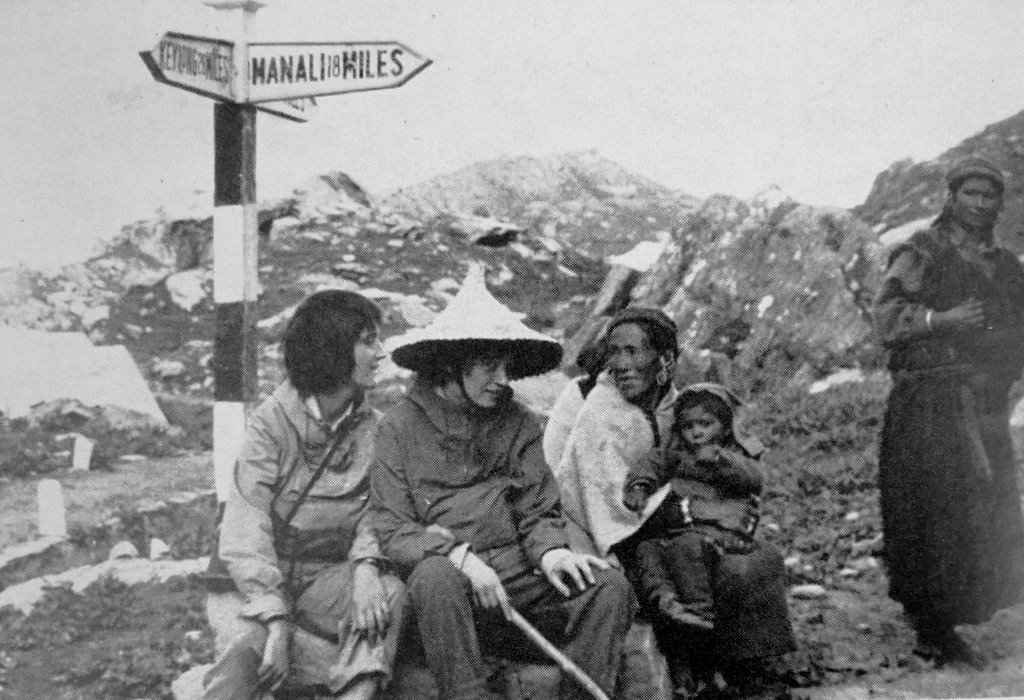

Davies, Sims, and Deacock ultimately found themselves in the Indian Prime Minister’s home via Lakshmi Bolar, an assistant to one of the Indian Cabinet Ministers who happened to meet the women at the Y.W.C.A. in New Delhi. After the permits were granted by the Indian government, the women trekked for 21 days, traveling over 300 miles into the Zanskar Valley. As the route had not been marked on a map at that point, porters guided the women through icy rivers and across snowy passes. Despite suffering from altitude sickness, they eventually reached the summit of an unnamed peak at 18,500 feet. They named the mountain Biri Giri, Hindi for “Wives Peak.” Davies, Sims, and Deacock were the first European women to venture into the region.

The people in the tiny villages of the remote Zanskar Valley were very interested in the Brits’ waterproof jackets and zippers, which the locals had never seen before. “Their greatest possessions are their freedom from both officialdom and an infectious cheerfulness,” Davies wrote. For Deacock, the lasting impression of the expedition was “to realize how privileged we had been to witness and partake, to some degree, in societies that were virtually strangers to the modern world that we know.”

Five months after leaving home and 16,000 miles later, the women watched their Land Rover land, by a crane, at the port in Harwich, England. They had driven through the difficult, hot, and dusty terrain of 12 countries. They had crossed the Inner Line. They had driven across Afghanistan unescorted. They had placed the Union Jack flag upon an unnamed peak at 18,500 feet of elevation. They had achieved what they set out to do.

But, as Davies puts it best, these achievements weren’t what made the trip so meaningful.

“They were as nothing, to us, compared with the friendships we made in the lands through which we passed. It is our great pleasure that we were able to find time to make so many friends, especially in India, Pakistan, and Zanskar itself. No doubt mountains and geographical explorations are important. However, much of the Himalaya has now been extensively explored, and one hopes that future expeditions can find more time to get to know the delightful people who live in those mountains.”

To celebrate the expedition’s 50th anniversary in 2008, photographer Martin Salter compiled the cine camera footage gathered for Ovaltine during the 1958 Women’s Overland Himalayan Expedition. The short film provides a rare and beautiful glimpse into the remote reaches of the Himalayas, a Tibetan Buddhist kingdom of the past, and the women who were brave enough to explore them.

Read more: This Daring Duo Drove Afghanistan’s Northern Road in a 1939 Ford