There is a mist that hangs over this small landlocked country in the Great Rift Valley. The clouds fall gently over the mountains, quietly holding the land and shrouded forests even when the sun shines. Rwanda is not the first place you would visit in Africa, but it’s a short distance from Tanzania or Kenya to experience a trip. As a photographer, my primary reason was to photograph the mountain gorillas. I had not thought about the Genocide Museum, which happened to be en route to Volcanoes National Park.

Kigali, the capital, is spotlessly clean, with a better road infrastructure than my hometown. I would overnight in what looked to be a first-class hotel before traveling to Ruhengeri and the national park. Before leaving Kigali, we stopped outside a very ordinary-looking Hôtel des Mille Collines—the besieged hotel in the movie, Hotel Rwanda, based on the actual events of the heroic efforts of the hotel manager, Paul Rusesabagina, to save the lives of more than 1,000 refugees, including his family, during the Rwandan genocide.

“100 Days of Slaughter” is the moniker for the genocide in Rwanda. During the spring of 1994, between 7 April and 15 July 1994, the slaughtering of 800,000 to one million of the Tutsi minority group unfolded in a tragic civil war. Through years of German and Belgium colonization, their incitement process resulted in a nation arbitrarily divided into the Hutu and Tutsi for no reason, with one favored above the other. The Hutu power party took control and urged people to help them get rid of the Tutsi—neighbors, families, friends, teachers, and even priests turned on each other.

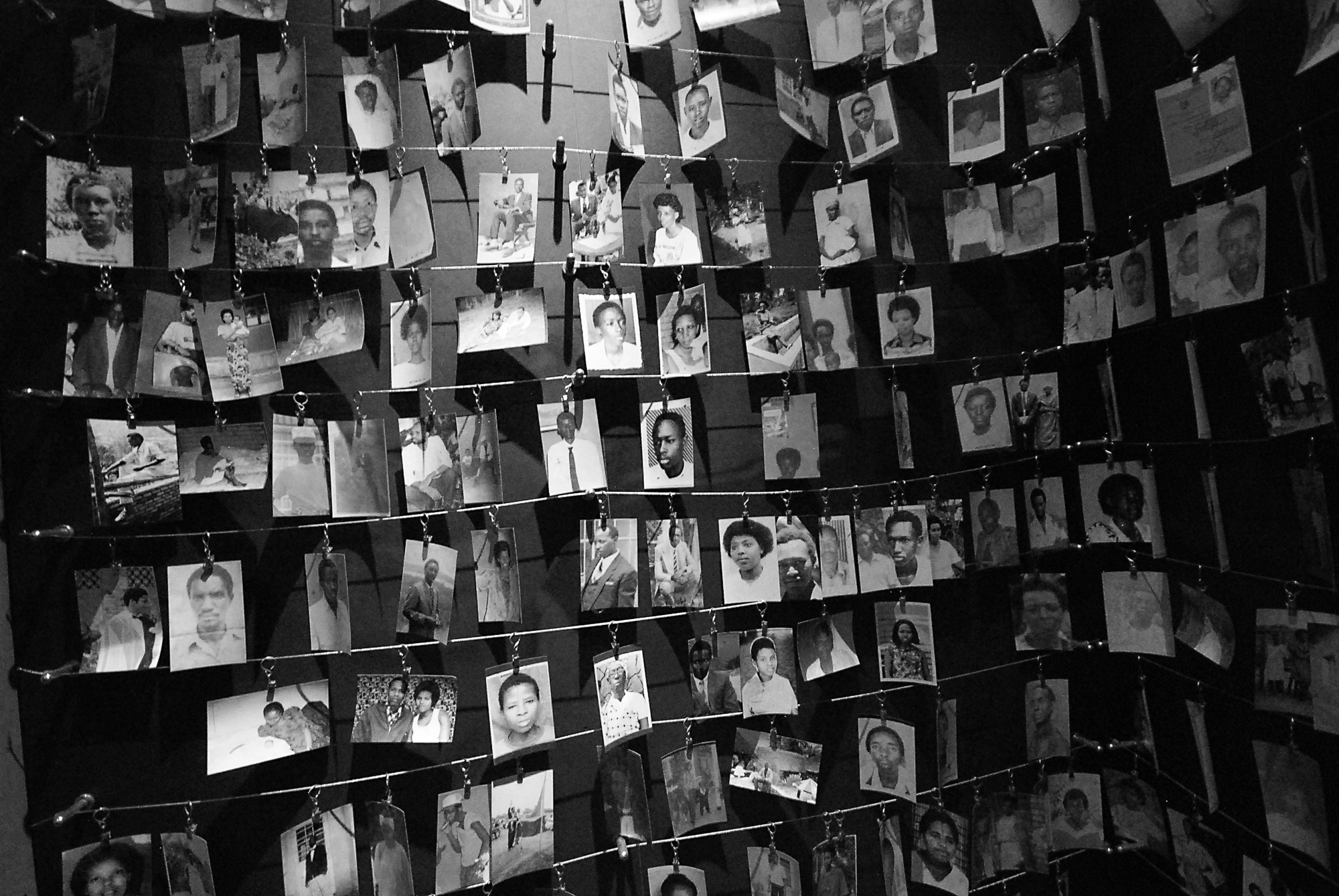

The Genocide Museum overlooks Kigali, a hushed neat building with gardens of remembrance to walk through or sit on a bench. Inside, the remnants documented, never to be forgotten. Hundreds of photos strung together, old, young, children, and babies—all gone in the name of power. There are bones, skulls, bits of clothing, and jewelry belonging to the lives of people who died catastrophically. It’s moving and emotional, and I left the museum with more understanding of the Rwandan people I’d seen move with joy and abandonment in the choreographed Intore dance.

Volcanoes National Park has 12 habituated mountain gorilla groups. In 1985, news came through that Dian Fossey had been killed, but her legacy through civil unrest and rife poaching has ensured that the mountain gorillas and their value to Rwanda are recognized and protected. A three- to four-hour hike up Mount Bisoke to visit a group called Ugenda was a dream for me. With garden gloves and protective gaiters against stinging nettles through the forest, a permit to see a group gives you one hour with them.

Suddenly through the thick canopy, the gorillas were there, and I was overwhelmed by their presence. The younger ones looked back with interest while the adults carried on grooming, eating, or resting. A juvenile moved closer, and I could look into his amber eyes—for a moment, the world was as it should be. And Rwanda at peace in the mist.

Squeezed above Burundi, surrounded by the Democratic Republic of Congo in the west and Uganda in the north, Rwanda and its neighbors are the central hubs of the mountain gorilla homes. With war-torn histories and heritages of poaching, it’s astonishing that the species has survived—and the people.

Dian Fossey’s gravestone, softened with moss and ground cover, was buried next to her beloved gorilla, Digit. She was heartbroken and never recovered from his brutal death. The locals knew her as Nyiramachabelli, meaning “the woman that lives alone on the mountain” in Swahili.

A juvenile gazes with shyness and shows off his skill between the branches, looking again for approval. There is something so human-like it is unmistakable; it’s hard to believe they are poached for bushmeat.

A mother gathers her baby in a hug, and through my lens, tears engulf me. After waiting so long to see these magnificent creatures, I suddenly feel a sense of invading their space—which is so scarce on this planet.

The Intore dance is also known as the warrior dance, which tells stories of battles and victories. Music and dance are inextricably part of a rich culture. Their pale grass wigs thrash through the air in grace and ballet only understood by Rwandans.

Set against the dark blue and green of the misty mountains, the echo of the Intore is electrifying. Sadly, many of the famous musicians and dancers died during the genocide. The dance speaks of a people who have lost and restored, if not healed.

The trip to Volcanoes National Park is approximately three hours from Kigali. My hosts from the gorilla trekking operation were friendly and knowledgeable, giving insights on Rwanda and the nation’s governance.

Kigali Serena Hotel is one of the big hotel chains in the capital, superbly run with all the amenities of a five-star venue. During the evening, I stood on the balcony and called my family in the Netherlands on WiFi. “You are where?” they asked.

As a passenger, I soon realized that driving in Rwanda would be taking your life into your own hands. The roads are fantastic, but the drivers are disastrous. Mountainous roads with blind corners and the oncoming vehicles or motorcycles would miss each other by inches. I closed my eyes and developed my own brakes.

In the bustling suburb of Nyabugogo, robots, as we know them (traffic lights to you), are useless. So is any pedestrian crossing or signage whatsoever. There are about 25,000 motorcycle taxis in Kigali, much more than the cabs in New York City. It’s the chaotic Africa I love.

There are curious children but no beggars in Rwanda. The people may be poor, but everyone grows vegetables on sometimes unforgiving terrain—a shining example for many of our countries on the continent.

Wherever you look, there are the patchworks of land tended with pride. The houses and shacks are elementary, but no nation should suffer from hunger in this day and age.

Kigali’s Genocide Museum is a visit that shocks a person to the core. It was a mere 27 years ago when the world stood quiet, not wanting to intervene in a catastrophe.

There was a bouquet with purple ribbons in remembrance of spring 1994 on the glass open part of the mass grave where over 250,000 victims have their resting place. It is a place for us, as visitors, to honor and for loved ones to remember and grieve.

“Never again genocide,” the haunting statement we cannot forget on the ribbon. The gardens are a balm saying we are restoring, we are forgiving, but we remember. In a manic moment, I felt the urge to scream. I didn’t.

It’s hard to understand humanity or its importance when faced with the skulls of those who died for nothing. We look into ourselves, trying to find some comprehension or intelligent reasoning, but there is none.

Hundreds of faces strung by the common thread of lives not yet fulfilled. A poignant moment to look into a face and wonder, who were you? What would your life have been? A life that ended in 100 days—we shan’t forget.

Our No Compromise Clause: We carefully screen all contributors to make sure they are independent and impartial. We never have and never will accept advertorial, and we do not allow advertising to influence our product or destination reviews.