On the back cover of her book, Road to Mekong, Jai Bharathi stands in a black motorcycle jacket, one foot propped up on the footpeg of her Bajaj Dominar 400 motorbike. Her look is casual, but Jai is anything but. This woman is a force.

From the South Indian city of Hyderabad, Jai’s first experience riding a motorized vehicle was in fourth grade. Her father brought home his first motorized vehicle, a new Luna TFR moped, with the intent of teaching Jai’s older brother to ride. But he made a point of teaching her as well. Her father showed her how to start the bike, explaining how to accelerate and slow down by applying the brakes. “Instead of making me feel dependent, he chose to teach me how to reach my goal,” Jai explains. “This small act of his instilled a confidence that later led me to unabashedly pursue anything that I truly believed in. I guess that was my dad’s first attempt, too, towards making me courageous.”

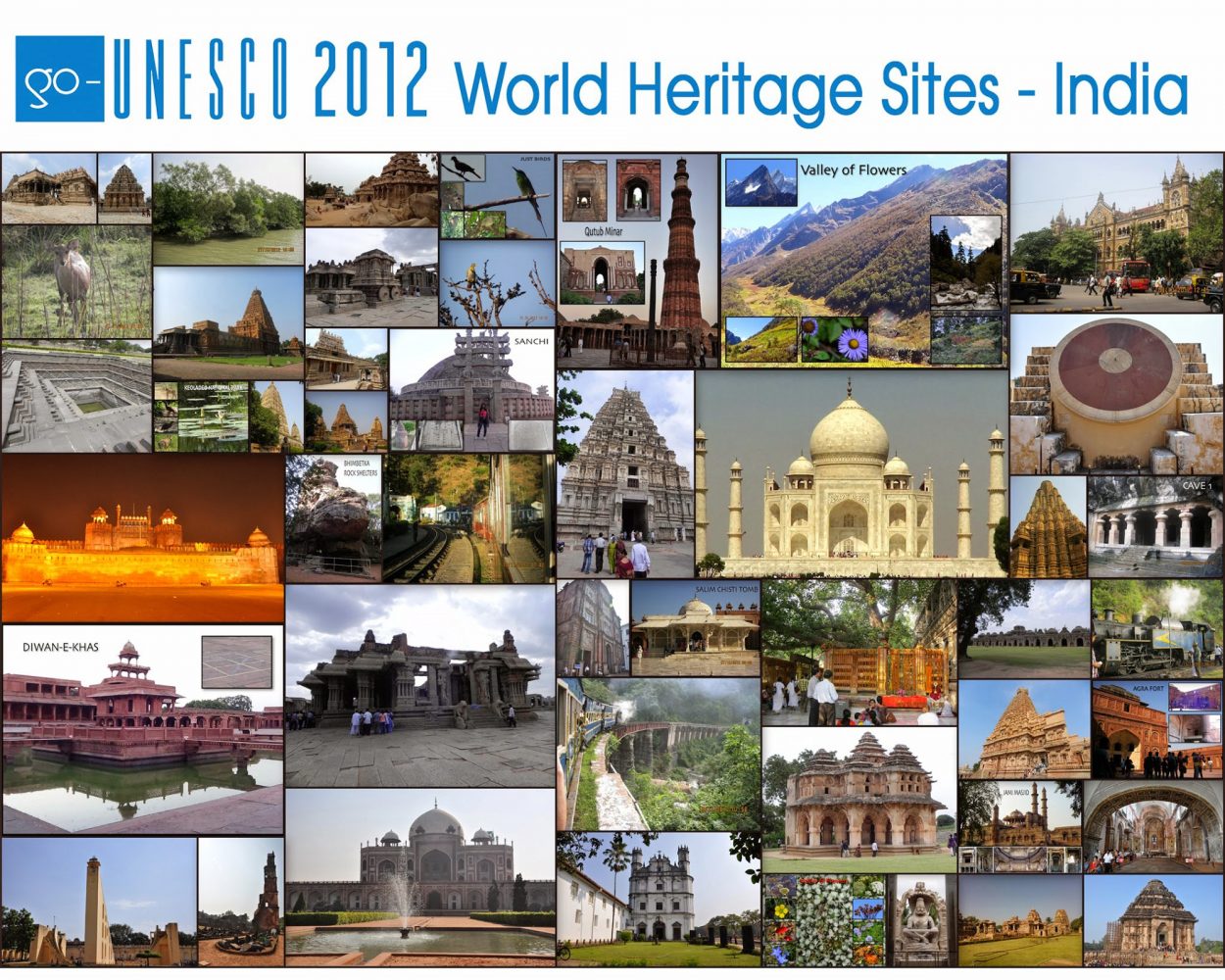

Jai’s courageous spirit led her to win India’s Go UNESCO Challenge in 2012, form the Hyderabad chapter of the Bikerni all-female motorcycle club, lead a team of four women bikers and eight crew members through a 17,000-kilometer 56-day expedition from India to Vietnam in 2018, and complete a month-long solo trip through the United States. And that’s just the tip of the iceberg. This former architect and marathon runner is currently shifting the culture of women’s empowerment and safety in India by offering two-, three-, and four-wheel training programs via her non-profit organization, MOWO (Moving Women) Social Initiatives Foundation. I recently sat down with Jai to discuss travel, women’s motorcycle culture in India, and what she has learned from her expeditions throughout India, Southeast Asia, and beyond.

In 2012 you won India’s Go UNESCO Challenge, which involved visiting all 28 UNESCO sites in India within a calendar year. What did this experience teach you about your own country and its people?

Travel has always existed in Indian culture in the form of pilgrimages. In Indian families, it is a standard thing. You go to one temple once a year and a couple of smaller temples every two or three months. During my parents’ time, the only travel they did was during a pilgrimage. There are so many stories, like that of Lord Buddha, where people walked to different places to explore. So, travel is an integral part of Indian culture.

During the Go UNESCO Challenge, I went to so many sites across India. I realized that the older generations had left a message for us. The way they built the structures or the way the natural heritage has been developed—everything has a message in it. The sites reveal how, at that point in time, the people lived or how they developed engineering marvels. No matter how many books you read or people you talk to, going to these places and exploring them will always bring you closer to the history of that place. During this challenge, I really fell in love with traveling across India. There’s so much to learn, and so many wonders within our own country.

You mention that the Valley of the Flowers was your favorite UNESCO World Heritage Site in India. Why?

The real challenge of the Go UNESCO Challenge is the sites are spread across the country, and some of the national parks are only open for two or three months during the year. At the time of the challenge, I was working for a UK-based design studio with a six-day workweek, so I had to complete my travel during weekends and holidays and do really tight planning. Reaching the Valley of the Flowers was a really key point. The day after I arrived, it closed for the season, so if I didn’t reach it on that particular day at that particular time, I wouldn’t have won the challenge at all.

I belong to the southern part of India, and in my city, we really don’t get to experience life in the mountains. We’ve only read about mountains in our books, so exploring them was something totally new to me. The Valley of the Flowers is a high-elevation valley in the West Himalayan region where some exotic flowers bloom for just two to three weeks of the year. After all of the ardours of traveling and finally being there, walking through nature was in and of itself bliss.

You were born and raised in Hyderabad and eventually returned after living in various parts of India. What are your favorite parts of your hometown?

Hyderabad is the capital city of the state of Telangana, which is the 29th and the youngest state of India. It is a historic city in Southern India which was built during the 1500s. Kings came from the middle eastern part of Asia and built hospitals and colleges, and those buildings are still around today. Charminar (translated as Four Towers) is an iconic structure built in 1591 AD as a mark of victory over a plague that hit the city during that period. If you really want to get the flavor of Hyderabad, walk through the markets of the Old City and visit Charminar at night when the structure is illuminated with lights.

You must also try the biryani (it’s world-famous) and enjoy the flavor of the city by walking through the old town at night. We are known across the globe for our food, and the city was chosen as a UNESCO Creative City of Gastronomy in 2019. Nobody returns from visiting Hyderabad without gaining a few pounds.

The good part about Hyderabad is that the charm and hustle and bustle of the Old City are still there, but the newer part was developed in a western corridor, preserving the original character of the city. The new part is booming with IT development. Amazon, Google, and Facebook have started up campuses, and it is becoming like the Silicon Valley of India.

In Road to Mekong, you state that Hyderabad has become a safer place, especially for women. How are female members of the Indian Police Service (IPS) in Hyderabad creating a safer environment for female motorcycle riders (and women in general)?

My role model growing up was Mrs. Kiran Bedi, the first female Indian police service officer and the first Indian and first woman to be appointed as the head of the United Nations Police and police advisor in the United Nations Department of Peace Operations. When I was a little girl, I would wait to watch her on the television. She has been the role model for courage for many young girls.

Since I wrote the book, there are so many more women IPS Officers moving up into senior positions. Award-winning Swati Lakra, Additional Director General of Police for our state Telangana, is just one example, and she is well-known. Swati Lakra started SHE Teams, a group of constables and officers specifically employed as an initiative by the Telangana government to tackle sexual harassment and women’s safety. The group talks to students attending college, and primary, middle, and high schools addressing both girls and boys about why women’s safety is really important. Courage alone won’t make us feel safer. We will only feel safer when everybody else around us helps keep us safe.

How do those living in rural parts of India react to a group of female motorcyclists?

Wherever we go, so many men want to take photos with us because we look fancy to them in our full riding gear on our motorcycles. When we tell them that we are traveling across the country, they become so excited. Every time someone wants to take a photo, I ask, ‘Where are all the women in your village?’ I know they are inside the house, so I say, ‘You know, next time, don’t be so inspired by us. Be inspired by your women because they can also do so many things like this.’

In 2013, you co-founded the Hyderabad chapter of Bikerni, an all-women motorcycle club with chapters spread across various cities throughout India. How did this lead to the development of your own non-profit organization, MOWO?

I learned to ride before age 13 and rode casually, borrowing friends’ bikes in college and for fun. I took up motorcycling more seriously in 2013 and discovered the Bikerni, an all-women motorcycle association, co-founded in 2011 by Urvashi Patole. I thought, ‘Why not add power to their wings instead of creating a new bird?’ So, I co-founded the Hyderabad chapter.

I love going on trips with my male motorcyclist friends, but there might be women who aren’t comfortable riding with male counterparts. Maybe they are married, or in their house it isn’t permitted to go hang out with other guys. This comes with social and cultural issues. Once a month, we hold a women-only ride, which could be 20 or 200 miles depending on how much time each of us has. After every ride, I get five to ten calls from women asking, “I’m also interested to ride. Can I join?”

After our monthly rides, several women would also contact us, asking for lessons. In India, the roads are filled with 75 percent men to 25 percent women drivers. I wondered why there weren’t more, so I asked the women. Many said that they didn’t know how to ride or didn’t have anyone in the house to teach them. I realized that many of us in Bikerni are just a bunch of women riding for our own passion or as a hobby. But, unknowingly, we are encouraging or inspiring so many women. Why not have a purpose for it?

We did a pilot, of course, teaching some women how to ride. We didn’t market the class as we wanted to only teach a few girls. The requests came pouring in, and we ended up teaching over 350 girls in a year. I thought, it is high time we create something purely for this. There weren’t many women-only two-wheel classes, so I started the MOWO (Moving Women) Social Initiatives Foundation, which is dedicated to empowering women by offering two-, three-, and four-wheel training. My previous experience volunteering for and being on the board of many other non-profits added up to my vision of empowering women through mobility with MOWO.

How has MOWO impacted women throughout India?

So far, we’ve observed that fear is the biggest challenge to learning. Conducting sessions on dedicated tracks in a controlled environment, keeping our training batches short, and offering an all-women training team helps our trainees feel safe and more confident on the road.

Our two- to four-week regular training programs offer road safety lessons and getting valid licenses from the Road Transportation Authority, as well as basic mixed martial arts training intended to improve individual confidence in accessing the vehicle and the roads. We also work with organizations to open up jobs in delivery services for our women. For example, Uber Eats joined hands with us to hire our women graduates as delivery partners. This partnership also offers flexible working hours to keep the job accessible to women. Graduates have also become fleet operators and tour guide partners.

The state of Telangana has invested in residential colleges for young girls from rural and tribal backgrounds, so we’ve partnered with these colleges in Hyderabad to provide free two-wheeler-driving training sessions for girls and young women as a first step of basic commute. In one college, we are training 150 girls, many with the dream to ride a Royal Enfield.

In 2018, you undertook a 17,000-kilometer, 56-day Road to Mekong expedition from India to Vietnam along the India-Myanmar-Thailand Trilateral Highway with a team of 12 people. What was the most challenging part of this expedition?

Traveling from India to other countries by land border is itself a very, very tricky process. If you have a US or European passport, the world is at your feet. Unfortunately, for us Indians, everything is a bit tedious with our passports. When you fly into any of these countries, most offer visas on arrival, but because we were going by land border, we had to get visas from the embassies. None of the embassies were located in my own city; they were all in different locations throughout India. We also obtained carnets for the bikes and the bus and International Driving Permits for the drivers. Collecting the documents for all 12 people, and putting the paperwork together was a challenge.

Another challenge was that I already fell in love with the result. I could already see us four women bikers in Vietnam on our motorcycles. Between paperwork and raising funds, it became so difficult to make that journey a reality. When I thought about it in my mind, it was very easy—you know, you pick the route, and you go. But for that to happen, we needed so many things, many of which were coming from multiple people, not just one person.

But the biggest challenge, as team leader, was shouldering the responsibility of the team’s safety during the trip. When we left from Hyderabad, everybody’s parents and family members came to see us off. They were all happy, but I could see that all of them were worried as well. In my city, there aren’t even men going on these expeditions (let alone women on motorbikes), so it was a big moment. I promised myself that, for all of these family members, I would bring all 11 people back exactly the way they left. I really wanted to see those smiles again when we returned.

What did you learn from your role as team leader during the Road to Mekong expedition?

My role was about more than the expedition; it was about people management. When the opportunity for this trip came up, I said to myself, it shouldn’t just be me. I will take as many people as I can. Who knew when I would get another opportunity like this again?

There were 12 people total on the expedition: four riders, two bus drivers, and a six-person team of photographers and videographers. Half of the team members didn’t have passports and had never stepped outside the country. Not only that, none of the team members knew each other, and their only link was through me. I didn’t choose to be the leader—I became the leader.

There was a surprise budget crunch at the last minute, and I was told to go with just a few people and do as many countries as we could. This was a life-changing moment for me. Because I didn’t have one important resource, what right did I have to kill their dreams?

I cried for one whole day and then allowed myself two days off to visit my best friend from college. When you change your circumstances, you suddenly wake up and see new possibilities. We brought in some more support and decided we were all going to go. If there were any problems, all 12 of us would return, but I wouldn’t cut anyone from the trip. We would do whatever it took to make it happen.

From September to October 2019, you undertook the Wheels of Will solo motorcycle trip across the United States to raise awareness about women and mobility and raise funds for MOWO. How did this trip differ from the Road to Mekong expedition?

This trip was much easier to organize as I was planning to do it solo. The responsibility of not having to care for a team in itself was a big relief. One thing I knew for sure was that I would visit the UNESCO World Heritage sites wherever I went, so that made route planning easy. My best friend and many of my close friends live in Dallas, Texas, so I started from there. The plan was to ride west to California, across to the east coast, and back to Dallas.

Whenever I have seen any American movies or series on Netflix or Amazon, they are all about road trips: camper vans, fancy Harleys, and people going outdoors and exploring. You know in your mind that the US is the place to go if you want to do a road trip. It is also a really beautiful country. Coming from a place like India, where we have a lot of history, the United States was definitely totally new to me.

The US was also the only place I didn’t have to look up the road conditions ahead of time. The infrastructure and facilities blew my mind—amazing is beyond what I can say. You can land up at a fuel station, fill up your tank, have something to eat, enjoy a coffee, use the washrooms. And no matter who I met, when they saw me, they would always wish me the best. Those little things mean a lot.

There is a beautiful organization called TANA, the Telugu Association of North America, which is the oldest and biggest Indo-American organization in North America. A large group of people from my particular region in India that have settled in the US have formed their own community, meeting for festivals, events, and supporting fellow country people. I was welcomed and invited to stay with many of the members’ families along the way. The world is filled with generous and kind people. All you have to do is believe in something and just do it.

Find Jai Bharathi Online:

MOWO Website: mowo.in

MOWO Instagram: @mowo.in

Road to Mekong Instagram: @roadtomekong

Read the Road to Mekong by Jai Bharathi