Buying a bicycle is a momentous event, akin to marriage: you are acquiring a partner. – Dervla Murphy, South From the Limpopo

It was no surprise to anyone, including Dervla Murphy herself, that a case of dysentery confined her to bed in Abbottabad, Pakistan. The previous week’s endeavors exposed the Irish cyclist to numerous perils as she crossed the 13,700-foot Babusar Pass, including (but not limited to) following a dubious pony trail over nine glaciers through knee-high snow, crossing icy rivers in tattered clothing, and wearing her bike around her neck while climbing inclines so strenuous they nearly led to desperation. The journey was fueled by beans, one chapati made from two ounces of maize flour, and snow.

Eventually, arriving at the head of the Kagan Valley, Murphy stopped at a popular spot for passing caravans, essentially a lean-to constructed of boulders and pine branches. After five cups of sweet tea and a supper of lentils and bread, a tribal chieftain arrived, announcing that the group in attendance was the first to cross the pass that year (1963). Dervla was later prescribed tablets for starvation and dysentery. “The recent combination of filthy food and flies and heat-stroke and over-exertion was bound to do some damage somewhere,” she wrote in Full Tilt: Ireland to India with a Bicycle. But, as Murphy would do time and time again, she rallied and carried on, eager for her next escapade.

Although the author and touring cyclist went on to write 26 books over the next 50 years, Full Tilt remains one of her best-known works. Published in 1965, named one of the best 10 cycling books by the Guardian and one of the 20 best travel books of the 20th century by the Times, Full Tilt is a collection of journal entries Dervla penned during her cycling trip from Dunkirk to Iran, through Afghanistan, Pakistan, and India. Her writing is straightforward, honest, reflective, and was often done by the dim light of an oil lamp or while resting on a charpoy. She didn’t beat around the bush, was a curious traveler, and captured her thoughts and opinions on local politics, the people she met, her beliefs about developing countries, and moving through the world as a woman. If upon further reflection, she changed her mind, she said so.

Much of what made Murphy an inquisitive and minimalist overlander originated in her youth. A bicycle and an atlas given as a birthday gift sparked a fantastical idea in Dervla’s 10-year-old brain: “I have never forgotten the exact spot, on a steep hill near Lismore, where this decision was made,” she wrote in her autobiography, Wheels Within Wheels. “Half-way up I rather proudly looked at my legs, slowly pushing the pedals around, and the thought came ‘If I went on doing this for long enough I could get to India.’”

Murphy spent 16 years caring for her mother, who developed rheumatoid arthritis early in Dervla’s life. “The hardships and poverty of my youth had been a good apprenticeship for this form of travel,” she recounted in Wheels Within Wheels. “I had been brought up to understand that materials, possessions and physical comfort should never be confused with success, achievement and security.” Following the death of her father in 1961 and mother in 1962, she departed for India on January 14, 1963.

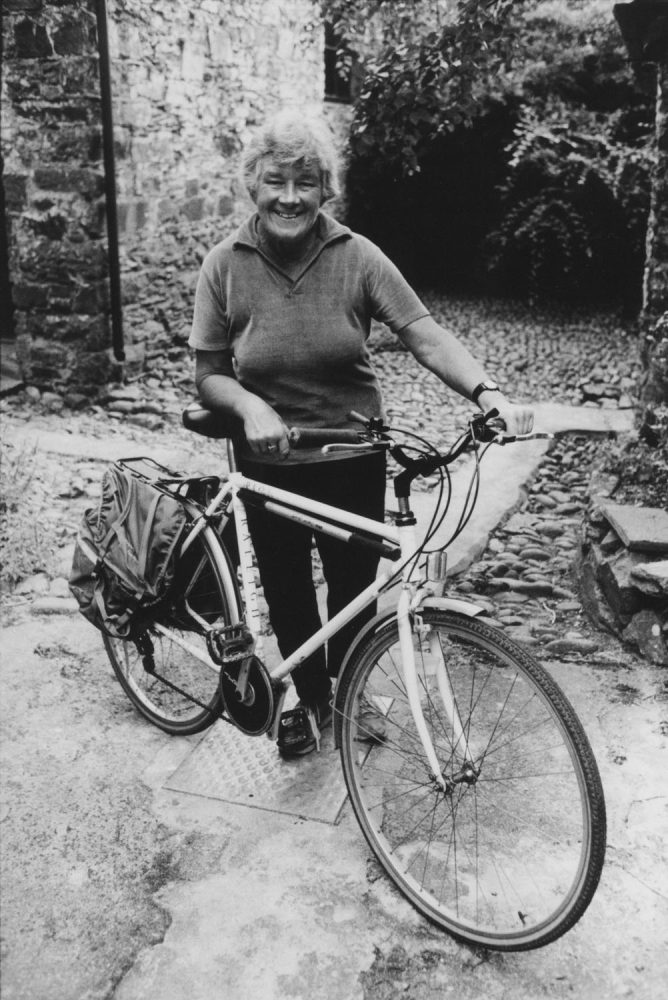

She loaded her Armstrong Cadet bicycle (known affectionately as “Roz”) with 28 pounds of kit: a saddlebag, bell, lamp, pump, and two panniers filled with clothes, toiletries, medical supplies, a .25 automatic pistol, four rounds of ammunition, maps from the AA in Dublin, Nehru’s History of India, and a copy of William Blake’s poems. She posted four spare tires to British embassies, consulates, and high commissions along her proposed route, which she planned in detail in order to receive her mail in a timely fashion. Between map studying sessions, Dervla escaped to the mountains surrounding Lismore, her local haunt, and practiced firing and reloading her gun. Although its presence in her pants pocket made her nervous, the pistol came in handy in dealing with a pack of wolves in Yugoslavia and in the Turkish town of Doğubayzit, where she fired a shot at the ceiling, scaring off a “six-foot, scantily-clad Kurd” who appeared in her room during the middle of the night. Fortunately, the weapon wasn’t needed in Afghanistan, where Murphy found herself in a strange shelter after waking from a nap. A member of the nomadic Kochi tribe noticed her sleeping without any shade, so he covered her with a tent made from goat hair before making a stealthy exit.

Murphy was adamant that for her, self-preservation, rather than courage, took over in times of fear. “This is perhaps the moment to contradict the popular fallacy that a solitary woman who undertakes this sort of journey must be ‘very courageous.’ Epictetus put it in a nutshell when he said, ‘For it is not death or hardship that is a fearful thing, but the fear of death and hardship.’” Certain practical decisions, such as staying at gendarmerie barracks (designed to protect travelers passing through Iran and Afghanistan in the 1960s) or balancing a bottle on top of a lockless door provided a sense of safety.

Photo credit (right): John Minihan

.

But Dervla wasn’t immune to the local talk about Afghanistan. Tales of bandits shooting American tourists, Communist-inspired trouble by the Russians, and visitors being stoned for taking photographs circled, particularly prior to crossing the border from Iran. “Despite myself all the fuss about the dangers of Afghanistan is having its effect on my nerves: probably a few days among the Afghans will soothe me down,” she admitted.

As she whizzed from Kabul to Kandahar, Murphy noticed the tug-of-war between the USSR and the US: electricity in small towns, paved city streets, silos, and choice seeds for crops were provided by the Russians, while the Americans implemented massive multi-year dam and road projects. “The more I see of life in these ‘undeveloped countries’ and the methods adopted to ‘improve’ them, the more depressed I become,” she wrote. “Having spoken to nine or ten young Afghans who have been exposed to Western influences, I notice an impatient feeling of contempt for their own country, an undiscriminating worship of everything American and a general restlessness, rootlessness and discontent.” One thing she did delight in, however, were the smooth paved roads.

Afghanistan in the 1950s and 1960s saw women in Kabul, the country’s capital, wearing pencil skirts, attending university, and becoming doctors, teachers, and lawyers. Still, those living in remote villages didn’t necessarily support the push of “modernization” implemented by larger cities. An Irish woman bicycling from her homeland was such a spectacle that the local people often assumed Dervla was a man. “The convenient illusion is fostered by the very short haircut I deliberately got in Tehran, and by a contour-obliterating shirt presented to me at Adabile by the US Army in the Middle East … It certainly is a curious experience to be a woman travelling alone in Muslim countries. Most of one’s time is spent in the company of men only, being treated with the respect due to a woman, but being talked to man-to-man.”

In the Afghan village of Mukur, Dervla spent time with 11- to 14-year-old girls in the maidens’ quarters; they were the first Muslim women she met face-to-face. The practice of purdah, or female seclusion, prevented her from interacting with as many women. “Physically they’re very beautiful … but the effect on their mental development of the purdah-system, as practiced here, is horrifying. We should feel grateful for having been born ‘free’ and ‘equal’ — something we take completely for granted though the majority of the world’s women do not yet enjoy this right.”

Determined to understand the intent behind arranged marriages, she engaged in prolonged discussions with several Muslims who shared the belief that parents, rather than young adults, know what’s needed to make a marriage work. Or, as Dervla put it: “Four parents in frank consultation are likely to arrange a more lastingly satisfactory mate than two hot-blooded young things who can’t see the trees for the sex.” She acquiesced, seeing the advantages and “psychological mechanism” of the system, but can’t help but wonder if they “miss the best of life’s adventures by not falling haphazardly in love after the manner of us decadent infidels.”

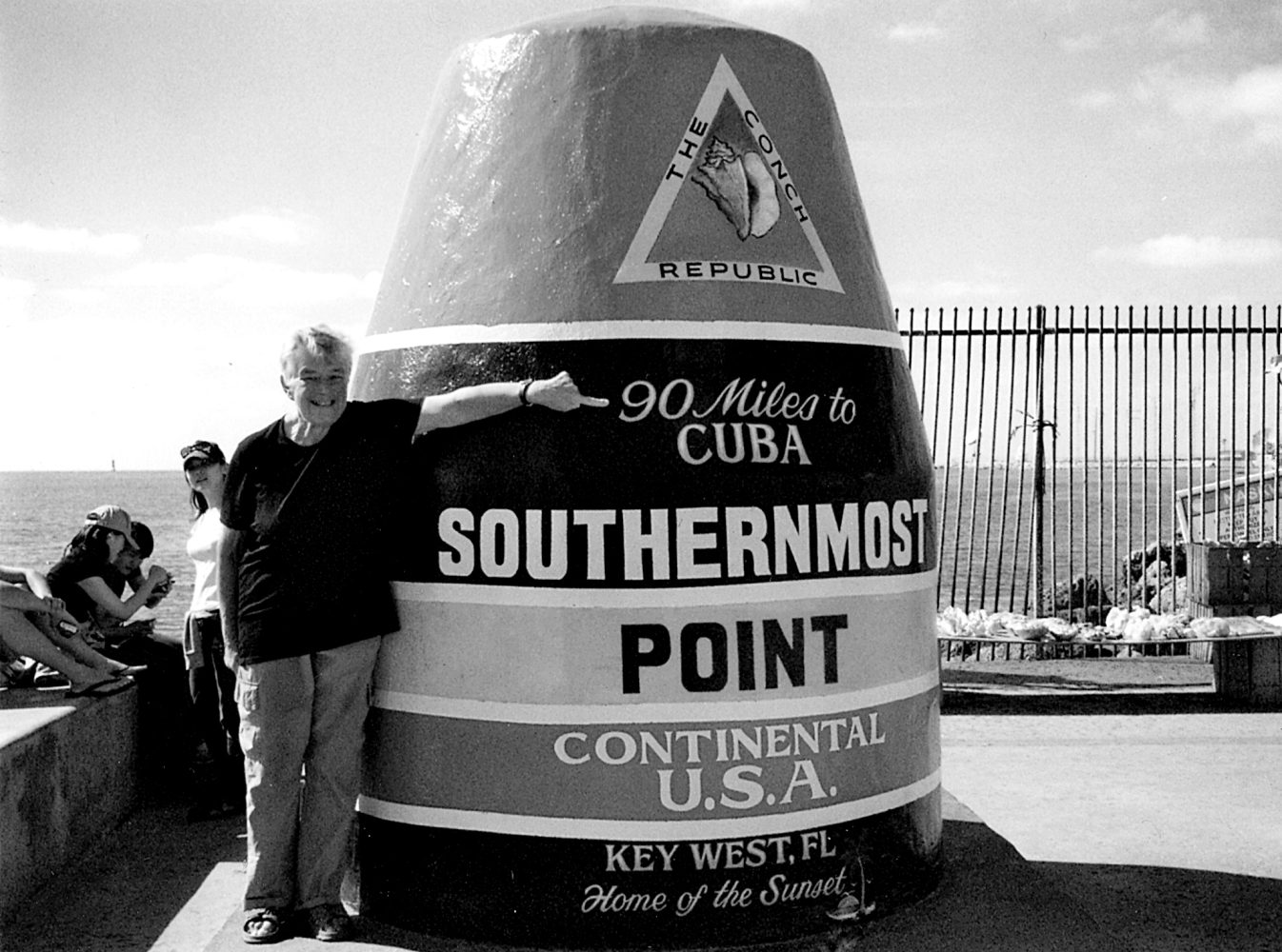

Despite the trials, tribulations, 114°F cycling days, heatstroke in the Himalayas, and a bout of dysentery, Dervla discovered much to enjoy about both Afghanistan and Pakistan before she concluded her trip in Delhi on July 18, 1963, nearly six months after leaving Ireland. Fifty-nine years later, 90-year-old Murphy died on May 22, 2022. But her memories, observations, and opinions span the pages of her books, remaining for future generations. The pages of Full Tilt provide an insight into Afghanistan before the Soviet invasion of 1979, when the east strived to meet the west. There, a young woman from Ireland arrived in a remote valley, surrounded by villagers staring in wonder and fear; she smiled. “Salaam alaikum.” Encouraged by the greeting, the crowd gathered closer, trying out the bicycle bell, whirling the pedals, running hands over the tires, and asking her where she was heading.

Our No Compromise Clause: We carefully screen all contributors to ensure they are independent and impartial. We never have and never will accept advertorial, and we do not allow advertising to influence our product or destination reviews.