Photos courtesy of vanburensisters.com

In August of 1916, sisters Adeline and Augusta Van Buren found themselves stranded in Skull Valley, an arid expanse of desert between Salt Lake City, Utah, and Reno, Nevada. Despite being part of the Lincoln Highway, the desolate track along which they navigated their three-speed Indian Powerplus motorcycles had vanished. Their water and fuel levels were low. It appeared that the sisters’ transcontinental trip was in jeopardy. Surely, after thousands of miles, this couldn’t be the end. Could it?

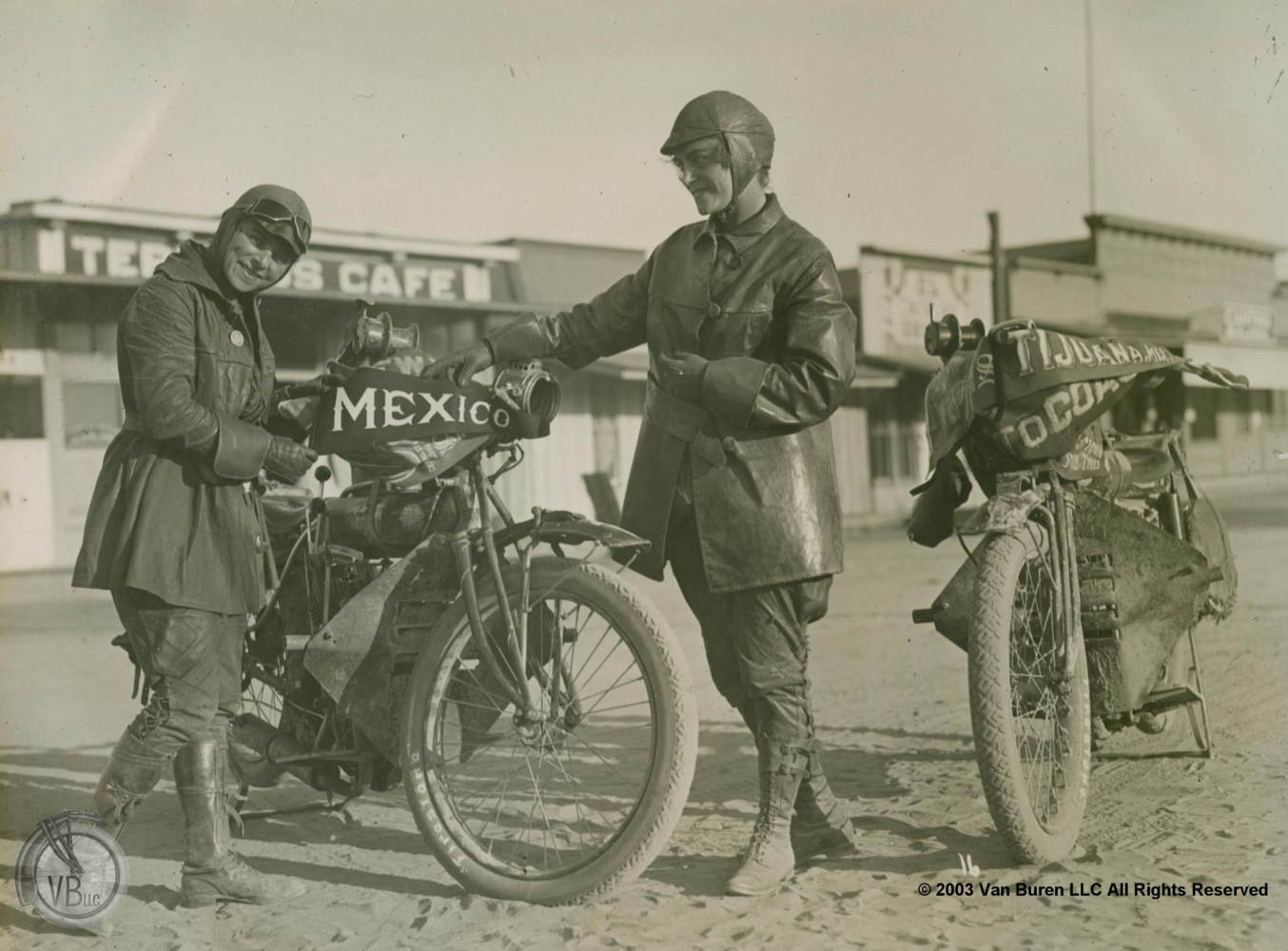

Astride a pair of Indian motorcycles and decked out in tan leather pants, caps, goggles, and long coats, Adeline, 26, and Augusta, 32, set off from Sheepshead Bay, New York, on July 4, 1916. They were about to undertake a historical 5,500-mile cross-country trek to Los Angeles, which aimed to prove that women could support military efforts and serve as dispatch riders. The sisters were keen advocates of the national Preparedness Movement, which sought to strengthen the military in anticipation of the Americans’ entry into World War I.

The Van Buren sisters’ cross-country trip was highly unusual for 1916. Motorcycle Illustrated reported on July 6, 1916, that the sisters expected “to show the brothers and fathers of other girls that ladies can ride and still not lose their most valuable asset, their femininity.” A writer at the Denver Post argued that the Preparedness issue was “serving as an excellent excuse for women to stay away from home, to display physical prowess in various fields of masculine superiority, and to display their feminine contours in nifty khaki and leather uniforms.” The sisters toured in a post-Victorian society where suffragette Susan B. Anthony and her followers championed the right to vote, the US Army had a strict policy against women’s requests to serve, and donning a pair of trousers could land a gal in jail.

Those familiar with the transcontinental route from New York City to San Francisco expressed doubt that two slightly built girls could accomplish the coast-to-coast trip. Indeed, the roads thus far had been terrible, and the sisters’ arrival date was delayed by weather and poor track conditions. “Roads didn’t exist back then,” Robert Van Buren, great-nephew of the Van Buren sisters, told the Telegram. “Basically, there were no road maps west of the Mississippi. They were just cow passes, dirt trails, wagon trails, things like that.”

According to William Murphy, author of Grace and Grit: Motorcycle Dispatches from Early Twentieth Century, the going was so tough that the women later revealed being so tired from struggling through the muddy conditions that they often fell asleep while riding, falling over into the mud. Despite these challenges, the sisters persevered. Crossing the frigid, mud-slicked Rockies, they motored to the 14,110-feet summit of Pikes Peak, becoming the first women to do so solo.

The 410-pound Powerplus bikes housed V-twin engines, which the sisters controlled via a hand-shifted gearbox and foot-operated clutch. Operating the motorcycles demanded the ability to multitask skillfully; Adeline and Augusta would have handled the throttle with a thickly gloved left hand while using their right to control ignition timing. Bumps and road obstacles were minimally absorbed by leaf spring suspension front and rear—it must have been a rough ride without shocks.

The sisters raved about their Firestone tires, which performed well, experiencing only two punctures over the duration of their journey. Prest-O-Lite acetylene gas headlights adorned the handlebars, on which the Van Burens strung cloth banners reading “Mexico” and “Coast to Coast.” With minimal room for luggage, they stored what little they had in two waterproof canvas bags.

It wasn’t until May 28, 1923, that the US Attorney General declared it legal for women to wear trousers. The riding breeches and puttee leggings worn by the Van Buren sisters weren’t just illegal–they would have been regarded as bizarre in 1916, especially in remote areas of the Midwest. “They were arrested a half-dozen times, too, in small towns between Chicago and the Rockies,” Adeline’s daughter wrote in an article for Ms. in 1978, “but each time they were released with only a reprimand, provided they got out of town fast.”

As the midday temperature in Skull Valley soared past 100 degrees and their 2.5-gallon fuel tanks inched closer to empty, Adeline and Augusta spotted a prospector navigating the desert by horse-drawn cart. Carrying a generous load of water and fuel, the prospector topped up the sisters’ gas tanks, replenished their water supply, and offered directions. The Van Burens continued through Nevada and California, with a quick stop in Tijuana, Mexico, before arriving in Los Angeles on September 8, 1916. They made history as the first women to cross the continental United States on their own motorcycles and the second and third women to drive motorcycles across the continent, following Effie Hotchkiss, who completed the route in 1915.

After returning to New York via the Southern Pacific Railway, the sisters applied to the Army to serve as volunteer dispatch riders. Although their requests were denied, the Van Burens continued to push for women’s equality. Adeline returned to her job as an elementary school English teacher, eventually enrolling in New York University’s Women’s Law Class in the fall of 1918. She continued teaching in the Bronx for many years and was married in 1925. Her daughter, Anne, was born in 1925. Adeline died in 1949 at age 59.

Augusta returned as head of a stenographic unit in New York City but continued to ride until her interest shifted to aviation. She received her pilot’s license in 1924 and joined Amelia Earhart’s Ninety-Nines, an association formed by the female pilots of the day. Augusta died in 1959 at the age of 75.

The Van Buren legacy continues. The sisters were elected to the AMA Motorcycle Hall of Fame in 2002 and inducted into the Sturgis Motorcycle Museum and Hall of Fame the following year. Adeline and Augusta’s great-nephew, Robert, and wife, Rhonda, completed a tribute ride in 2006 to raise funds for the Intrepid Fallen Heroes Fund and celebrate the 90th anniversary of his great-aunts’ historical trip.

In 2016, the sisters’ extended family organized a centennial ride with womensmotorcycletours.com. At least 100 women riders (including Adeline’s great-granddaughter and great-great niece) traveled much of the same route the two sisters did a century earlier. The group wore T-shirts printed with a phrase Augusta once told a West Coast reporter: “Woman can, if she will.”